How Laura Poitras Finds the Truth

The director has a knack for getting people to tell her things they’ve never told anyone else—including her latest subject, Seymour Hersh.

Laura Poitras

(Jan Stürmann)Pasted on the wall next to the locked steel door that seals Laura Poitras’s studio from visitors and intruders is a black poster depicting a PGP key that the filmmaker has used in the past to receive encrypted messages. It makes sense that this key—a sort of invitation to send her a secret message—is the only identifiable sign that Poitras edits her movies in this building; she did, after all, once receive what is likely the most famous encrypted message of the 21st century, from Edward Snowden, who was the subject of her 2015 documentary, Citizenfour.

Milling about in the hallway outside Poitras’s Soho studio, which shares a floor with a jewelry company and a luxury real estate firm, I can’t help but think of how oddly commonplace the pasted PGP key is. Two decades ago, no one thought about their privacy with much rigor, but it is now something that we try to guard daily from incursions.

Poitras has a lot to do with these developments. She had firsthand experience of the repressive power of the US government long before Snowden came into her life and revealed the full extent of the National Security Agency’s mass surveillance efforts around the world and against US citizens. After the release of her 2006 documentary, My Country, My Country—which followed an Iraqi doctor, Riyadh al-Adhadh, running for office during the country’s first civil elections, which took place under US occupation—Poitras became a frequent target of the security state. Between 2006 and 2012, she was stopped and questioned by the Transportation Security Administration more than 50 times during her travels. She was also placed on a Department of Homeland Security watch list and flagged with the highest possible threat level.

The harassment Poitras faced was intense: During one trip to New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport, her laptop, camera, and cell phone were taken and held for 41 days; another time, a Newark Airport officer threatened to handcuff her for taking notes during an interrogation, saying the ballpoint pen in her hand could be credibly seen as a weapon. Poitras asked if she could get a crayon to continue her note-taking; the officer said no. (She wouldn’t learn until 2017, through a FOIA lawsuit, that the government had deemed her to be a threat.)

These incidents made Poitras realize very quickly that she needed to guard her privacy—and, by extension, her ongoing work—fiercely. The methods she used, such as encryption and fastidious backups of her material, may have once been seen as niche, but they are now as common as a Signal chat. It is, if anything, conventional wisdom to protect your devices from the prying eyes (and fingers) of border agents before you enter the country, especially now that you can be denied entry for messages expressing criticism of the Trump administration.

Even so, we willingly sacrifice our privacy every day as we tap to pay at the train station turnstile or do one of the countless other things that require us to hand over our location and data to actors we neither know nor trust. So when Poitras lets me into her studio, after punching a code into a panel next to the metal door, the first thing I want to know is what she thinks of our relationship to privacy in 2025. Have we lost the fight—or even the desire—to keep our business to ourselves? Poitras doesn’t think so: “If I ask you for the keys to your house, you’re gonna say, ‘No thanks.’”

It’s a characteristic quip, at once quick-witted and hard-nosed. Poitras, I come to appreciate fully during the morning I spend with her, is both a disciplined political artist and an interlocutor that people feel at ease with. It’s why her subjects tell her things they have never told anyone else, which is especially true of the man at the center of her latest film, Cover-Up: the journalist Seymour Hersh.

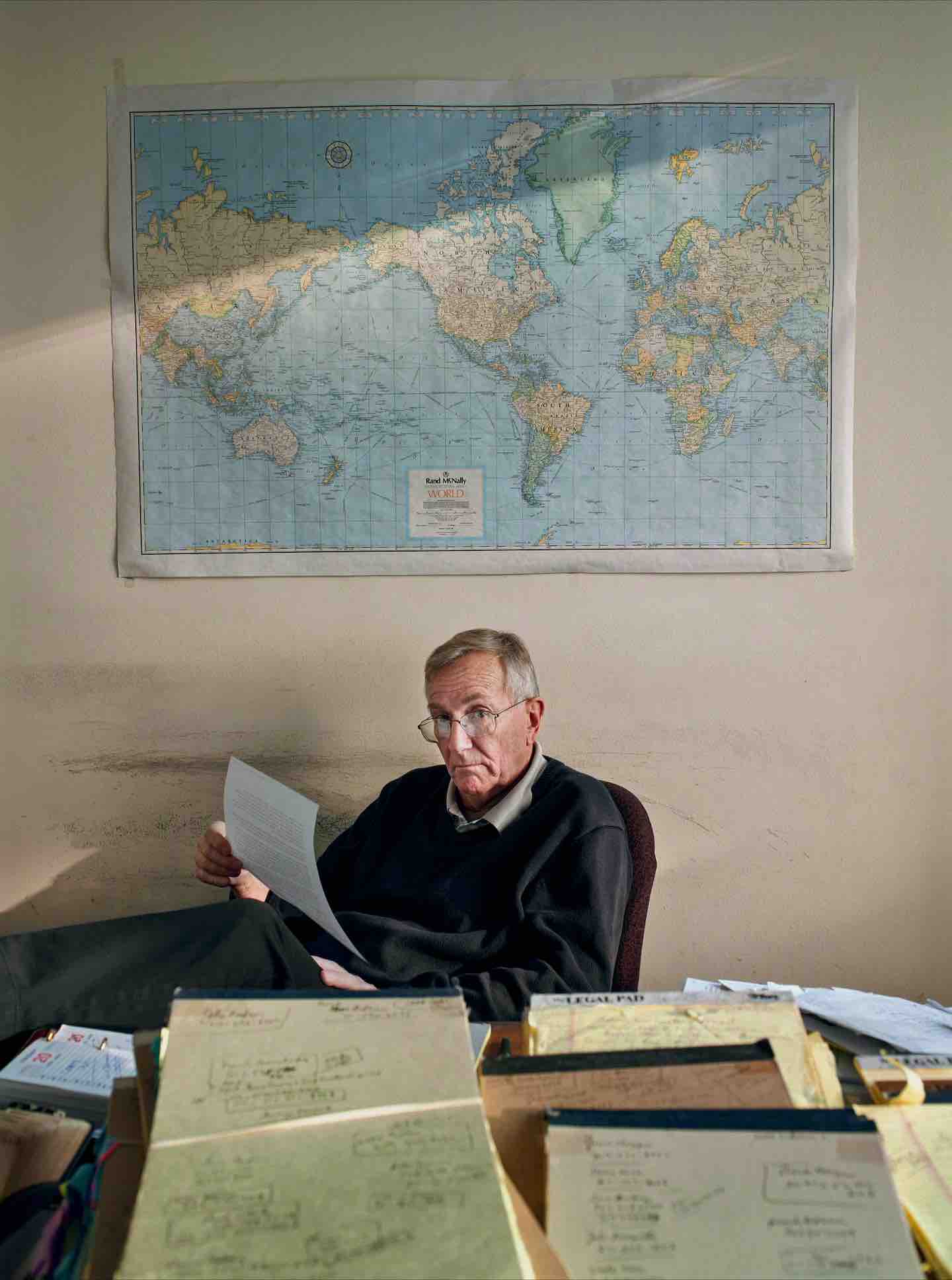

Poitras originally conceived of making a documentary about Hersh in 2005, but it took her nearly two decades to convince him to sign on. Finally, in 2023, Hersh relented, allowing Poitras, her codirector Mark Obenhaus, and a team of archival producers into his inner sanctum: his home and office in Washington, DC, which is filled to the brim with files that record a counter-history of the United States.

Poitras says she’s been chasing Hersh all these years because she thinks his reporting can be used “as a lens through a history of American atrocities.” The first of those atrocities was the massacre at My Lai, when US soldiers killed over 500 Vietnamese civilians, many of them women and children. And the latest of the atrocities that Cover-Up tackles is the US-backed Israeli genocide in Gaza, which has killed upwards of 70,000 people. Indeed, the film is quite intentional in its bookending of these events: They are important markers in the history of America that Hersh has been writing since 1969, when he was the first reporter to expose what had happened in My Lai—a story that lays bare how this country and its political leaders have fostered an “enormous culture of violence,” he says. The very point of his work, Hersh tells Poitras in Cover-Up, is that “you can’t just have a country who does that and looks the other way.”

My Lai hangs heavily over Cover-Up. The film might not have existed in the first place if not for the fear that the massacre would be forgotten: Before Poitras reached out, Obenhaus and Hersh were working together on a documentary about My Lai and its contemporary relevance. But they were struggling to find funding, so when Poitras asked again to profile Hersh, he introduced her to Obenhaus. The two filmmakers then decided to collaborate to tell the reporter’s story.

The kind of work Hersh does might crush the spirit of most journalists. While it’s true that his writing has done more to change the course of history than that of most who pick up a notepad—his reporting on domestic spying by the CIA led to both the Rockefeller Commission and the Church Committee, and his exposure of US crimes overseas in Vietnam and Iraq caused firestorms in two different centuries—the plaudits do little to abate Hersh’s bleak outlook. “He says in the film that he despairs a lot,” Poitras says. “But I also think that his act of continuing to report is an answer to [the question] ‘What do you do with the despair?’ You have to channel it. And that’s what he does.”

Another reason to make this film now: “Journalism is in crisis,” Poitras says. “But one of the things about the film is, it’s hopefully showing that this crisis doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and it’s been happening for a long time. One of the things that I think is really interesting about Sy is his consistent critique both of state power, abuse of power, and also legacy news organizations, and how they are oftentimes self-censoring or capitulating to government power or pressure.” Ultimately, she adds, “the heart of the film is to help the audience understand that we have been lied to over and over again by the government, and that we need to be more skeptical.”

Some of Poitras’s skepticism is directed toward Hersh himself, who, for all his successes, has been wrong more than once over the last four decades. One of the most high-profile mistakes that the film covers came during his writing of a 1997 book about the Kennedys, The Dark Side of Camelot, when Hersh was almost duped into buying forged documents that claimed to detail the full extent of John F. Kennedy’s affair with Marilyn Monroe. The dustup was covered widely, and Hersh was hauled in front of TV cameras to explain to cable-news audiences how he had almost been played for a fool.

But arguably the most consequential misstep of Hersh’s career came in 2014, when he wrote a report for the London Review of Books challenging accounts that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad had subjected his own citizens to chemical warfare. Hersh alleged that it was Syrian rebel forces, rather than the government, that had used sarin gas in a 2013 attack in Ghouta, at the height of the country’s civil war. For years, Hersh defended his reporting, despite the sizable damage it did to his reputation. But it’s clear now, with Assad in exile, that the former president did in fact subject his citizens to the worst violence imaginable. Among the most remarkable moments in the film is when Poitras challenges Hersh on his Syria reporting and he admits that he misjudged Assad and got the story wrong.

“We obviously needed to tackle some of this reporting that I couldn’t defend,” Poitras says. “And, I mean, I know people who were tortured in Syria, and it was reporting that I think was problematic, so we had to ask it…. It was the same with JFK, which allowed us to raise larger questions about the dangers of investigative journalism: [What are] the dangers of being played? What are the dangers of being seduced by power?”

For his part, Hersh is glad that Poitras asked. “No one is flawless…. I chase stories…but so it goes,” he tells me over e-mail. And while Poitras got Hersh to admit fault on camera, his Substack, which he launched in 2023, has been an outlet for him to reflect on his career, too. (It’s also where he does most of his reporting these days, most notably a story alleging US involvement in the destruction of the Nord Stream pipelines in 2022, but also reporting on the crisis posed by a senescent Biden and Trump’s cosigning of Israel’s attacks on Iran.) In a post from last year called “The Fall of Bashar Assad,” Hersh explains how he cultivated sources in Syria, among them Assad himself, whom he met during the Iraq War. Hersh doesn’t mention the LRB reporting in the post, but he makes it clear enough that he should never have taken Assad at his word.

One of the arguments that Poitras and Obenhaus have with Hersh over the course of the film concerns his use of anonymous sources and whether single-source reporting is enough to buttress the facts of a story. They challenge him to consider whether his sources might not always be trustworthy, a subject so touchy that he snaps back, implying they have no idea what they’re talking about.

“Laura and I both share some unease with single-source reporting,” Obenhaus tells me over e-mail. “That said, some of Sy’s important reporting has been based on single sources. Same for many investigative journalists. I think it is an issue that is unresolvable. One wishes there could be multiple sources for every story, but if that were the only standard, reporters like Sy would have a hard time operating.”

In the end, Hersh’s record as an investigative reporter is still one to envy. Perhaps the most accurate take on his work came from then-President Richard Nixon, who once fumed to Henry Kissinger, “I mean, the son of a bitch is a son of a bitch, but he’s usually right, isn’t he?”

When I watched Cover-Up at the Paris Theater in Manhattan, I was struck by the reaction from the crowd, many of whom were either encountering Hersh for the first time or knew only a little about his work. Poitras presents him unvarnished—prickly and cantankerous, but also a schmoozer full of brio. We hear him talk to sources and editors with both contempt and love and watch him bristle when Poitras and Obenhaus press too hard; at one point, he requests that they stop filming after he feels they’ve violated the sanctity of his files and could accidentally expose some of his sources.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The crowd, I think, was won over by Hersh, charmed by his crusty persona and amused by his wilder comments. But the audience was also dismayed by the totality of the misdeeds that he revealed to the world, much of which has been obscured by the passage of time. After the film ended, the director Mira Nair moderated a conversation with Hersh and Poitras. Hersh told Nair that Cover-Up’s biggest achievement is that “it brought back for Americans what happened in Vietnam, and it brought back what happened in Abu Ghraib. It brought back things in a way that stuck.”

Even so, there’s much that the audience will never see: hours of conversation cut from the film. At her studio, Poitras shows me the storyboard she used to organize the documentary’s exacting structure, which, rather than plod linearly through Hersh’s life, juxtaposes different moments from his career in order to show their continued resonance—to give the viewer the necessary knowledge to link Vietnam to Iraq and Gaza. Among the more loving episodes not included in the film, Poitras tells me, is a story Hersh told from his youth, after he graduated from the University of Chicago and was still lost and unable to piece together what to do with his life. Before college, he’d worked at his father’s dry-cleaning shop, but a community college professor urged him to aim higher. Hersh did, but his postgraduate years were still unmoored, and when he was working the liquor counter at a pharmacy, the novelist Saul Bellow walked in. He was a former teacher of Hersh’s and was shocked to see him there. A short time later, Hersh joined the City News Bureau of Chicago and decided to start his life in earnest.

Hersh is now 88, but the treatment Poitras gives him in Cover-Up revels in his boyishness. Despite the horrors he’s seen, despite how despondent he might feel, his journalism gives him purpose, which is more than most can say. Neither Hersh’s nor Poitras’s work is likely to leave people with a sense of hope or optimism, it perhaps can give us something better: the truth.

More from The Nation

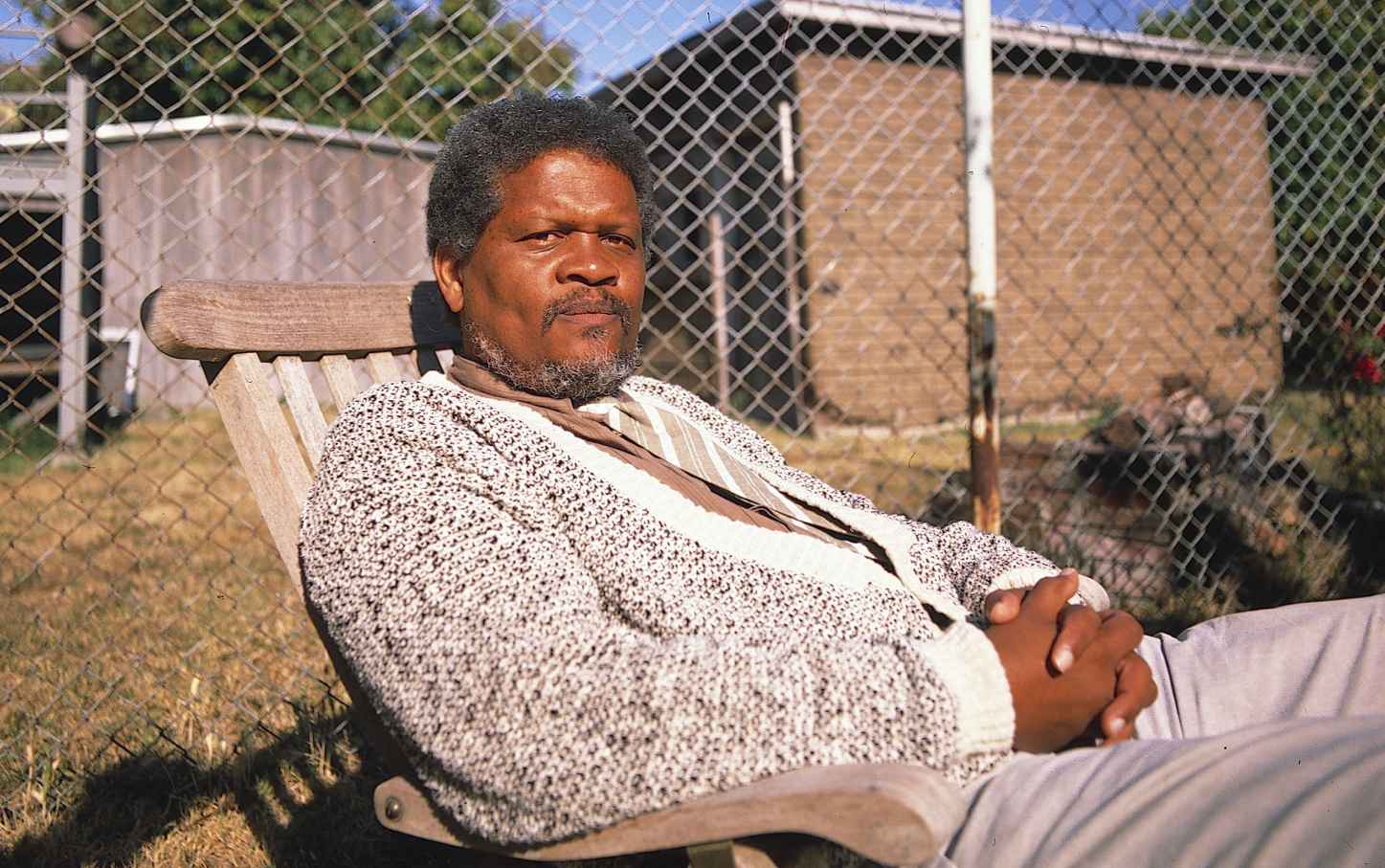

Ishmael Reed on His Diverse Inspirations Ishmael Reed on His Diverse Inspirations

The origins of the Before Columbus Foundation.

How Was Sociology Invented? How Was Sociology Invented?

A conversation with Kwame Anthony Appiah about the religious origins of social theory and his recent book Captive Gods.

How Immigration Transformed Europe’s Most Conservative Capital How Immigration Transformed Europe’s Most Conservative Capital

Madrid has changed greatly since 1975, at once opening itself to immigrants from Latin America while also doubling down on conservative politics.

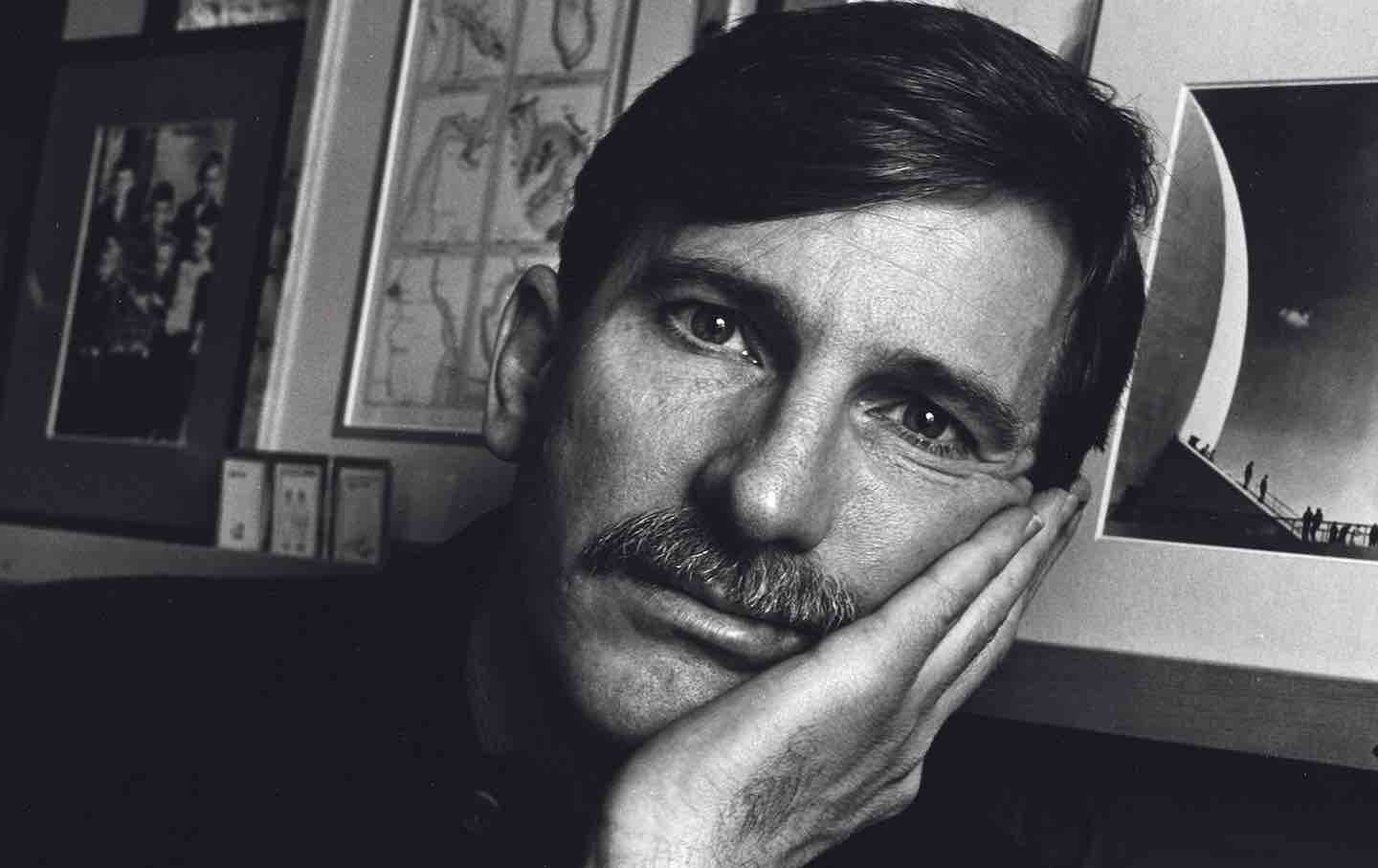

A Living Archive of Peter Hujar A Living Archive of Peter Hujar

The director Ira Sachs’s transforms an intimate interview with the photographer into a film about friendship, routine, and why we make art at all.

George Whitmore’s Unsparing Queer Fiction George Whitmore’s Unsparing Queer Fiction

Long out of print, his novel Nebraska is an enigmatic record of queer survival in midcentury America.

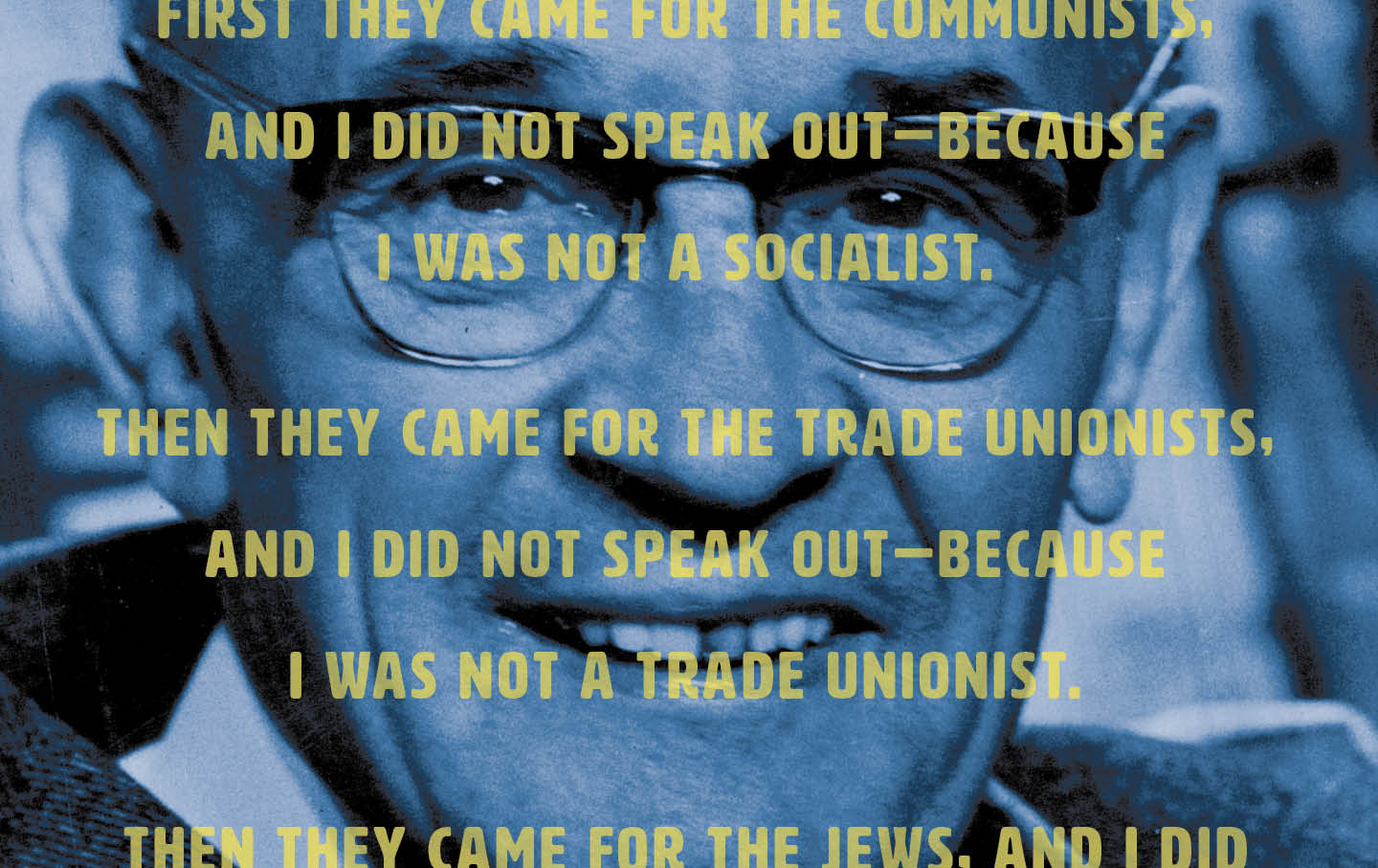

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?