One Solution to the Housing Crisis Is in Plain Sight

The shortage can be addressed not through costly new development but by reusing existing buildings.

It’s become impossible to ignore the housing crisis’s elephant in the room: the link between real estate speculation and carbon emissions. Supply-side housing advocates’ insistence that simply increasing new construction is the ne plus ultra of resolving housing shortages elides the environmental cost of all those new buildings. We’re left to assume that spewing tons of carbon into the atmosphere is a necessary evil. But these emissions are epic in scale: According to the European Commission, the construction industry is the largest single producer of CO2 emissions, accounting for over one-third of all the greenhouse gas emitted globally. Air travel, for comparison, is a meager 5 percent.

Climate change is not a technological problem. The field of architecture has pioneered many highly effective green tools since the 1970s, from LEED and Passivhaus to solar panels and geothermal heat. We have the technology. But since buildings are prioritized as a source of financial speculation, we’re incentivized not only to continue using outdated, carbon-intensive construction processes, but to raze and rebuild over and over again as though infinite sources of energy and materials remain in this burning world. By 2050, over 2 billion square meters of existing space—the equivalent of half of Germany’s building stock and more than that of Berlin or Paris in their entirety—will have been demolished in Europe alone.

Renovation has gotten a bad rap, in part because the capitalist class is just as happy to use it as a way of displacing families when they can’t afford to raze and build new. However, when paired with policies that keep tenants in buildings—such as community land trusts, rent control, or rent freezes like the one proposed by New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani—renovation can extend both the life of buildings and the cultures within them. There are a lot of existing buildings we can make productive use of if we think creatively.

Such reuse is not at all incompatible with other popular reforms such as upzoning, single-stair construction, or the development of unused parcels of land in urban areas, such as parking lots. Around the world, there are millions of vulnerable properties that can and should be renovated to more sustainable ends. There are the two-flats in Chicago that are prime targets for teardowns and usually replaced by single-family homes. There are midcentury European housing blocks prone to gentrification and speculative demolition. There are industrial and commercial buildings, including office towers, that no longer serve their original purpose in our postindustrial, globalized society.

Debates about housing don’t talk enough about the housing that’s already there. During the mass building campaigns of the 19th and 20th centuries, millions of tons of carbon were already spent in order to house the rapidly expanding populations made possible by advancements in the quality of life. Those emissions, called embodied carbon, are produced by new construction and remain in existing buildings. When demolition releases embodied carbon, that spent energy cannot be recaptured. It is gone forever. If your goal is to extract as much profit as possible, you’re liable to demolish a completely fine building and replace it with a newer, more profitable—and often smaller—one. What if we resisted this logic and did so in a way that preserved rather than jeopardized affordability?

This is the question posed by the European collective HouseEurope!, which made a splash at this year’s Venice Biennale for being one of only a handful of explicitly political projects (amid a sea of AI slop and dancing robots) in the Arsenale, its main exhibition space. In a series of films, the collective—which has the support of a number of important architects such as OMA’s Reinier de Graaf and Pritzker Prize winners Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal—convincingly demonstrates the link between architecture, the shadowy world of real estate, and climate change.

By shedding a light on financial speculation—the need for hedge funds, private equity, and banks to use buildings as illiquid collateral in investments, driving up housing costs and hastening gentrification—HouseEurope! links the practice of renovating aging building stock for use rather than exchange with a politics that stands in defense of both people and the planet. Their logic is that even if renovation has its limitations, it is still a better way to preserve affordability than razing and rebuilding, which has higher operational costs. Many buildings that have fallen completely out of use are viable sources of housing with the right adaptations.

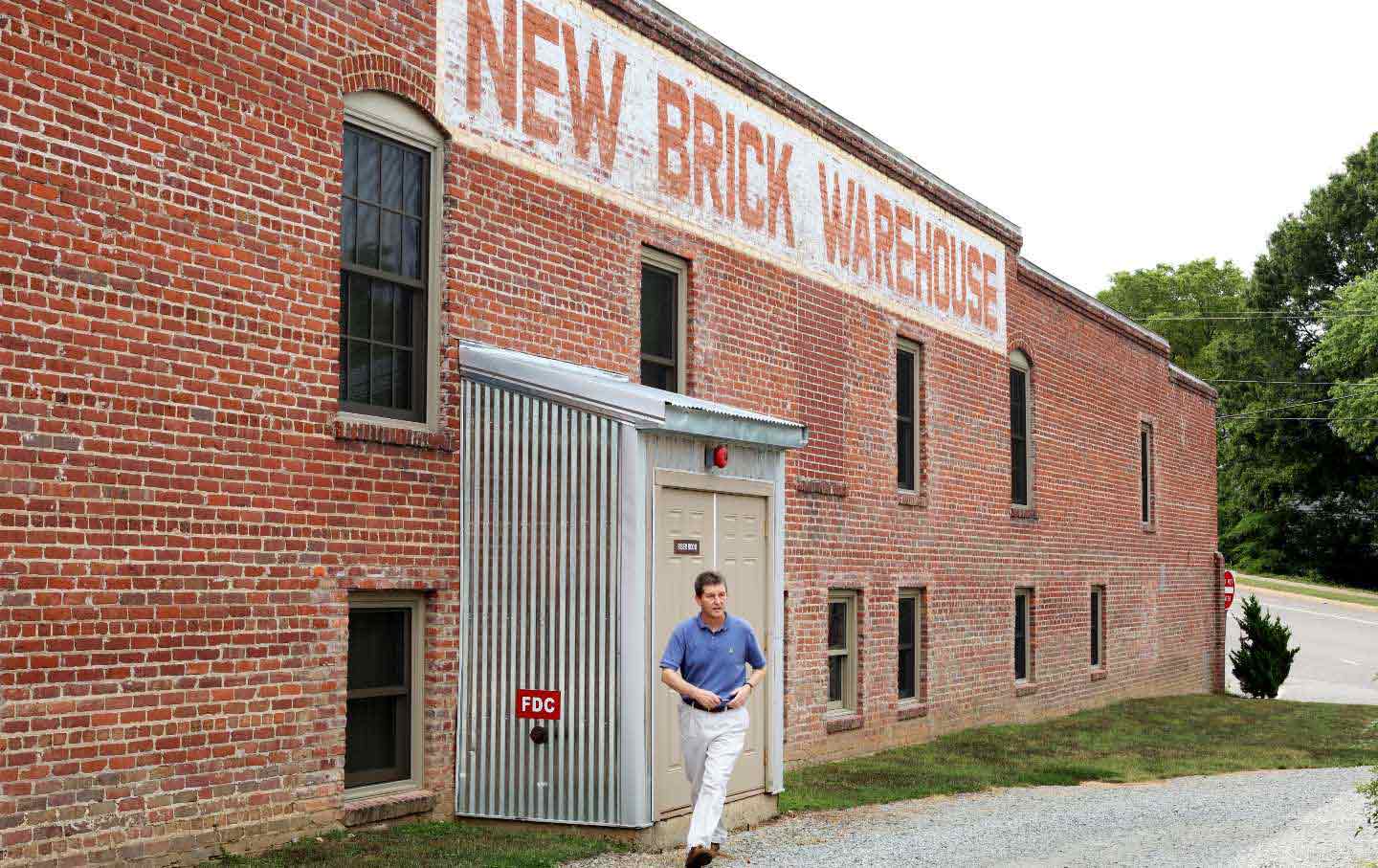

Olaf Grawert, a principal at the firm B+ and a member of HouseEurope!, describes renovation as a generative process. “The moment the system considers a building a ruin…it’s considered trash. The building loses all its value…. And in this logic, we were successful in developing buildings because we bought them for the costs minus the demolition costs, but then we never demolished.” While HouseEurope! is a European initiative, Grawert cites as an example a building his firm did in the US, a nonprofit art center in Minneapolis called 0240 Midway, where they were able to buy an abandoned parking garage with very little money—the building was already there and therefore did not require demolition financing—and convert it. The question for Grawert and his ever-expanding network of colleagues is: How can such renovations become the norm?

HouseEurope! has a plan of attack, something called the European Citizens Initiative (ECI), which is essentially an EU-wide ballot initiative, a tool for direct democracy that enables citizens across the EU to propose new or improved legislation. If, within a one-year time frame, 1 million EU citizens from at least seven countries support a cause, the European Commission must consider the proposal and form a working group. ECIs are generally concise, so HouseEurope!’s proposal is simple: “We demand a right to reuse for existing buildings based on three key pillars: (I) tax reductions for renovation works and reused materials, (II) fair rules to assess both potentials and risks of existing buildings, and (III) new values for the embedded CO2 in existing structures.”

While it is important to consider these goals within their European context (the EU has pledged to be carbon-neutral by 2050), they are not so far-fetched for us Americans. There are already tax incentives in states like Colorado to promote the use of lower-carbon building materials and anti-teardown mandates finally being put into effect in Chicago. Local Law 97 in New York, although beleaguered by industry threats, sets climate pollution limits on buildings over 25,000 square feet, with the goal of reducing the buildings’ emissions by 40 percent by 2030 and to net zero by 2050. But HouseEurope!’s platform asks a more inspiring question than just “What legislation can we pass?” It invites the world of architecture to adapt rather than dominate, to embrace maintenance over destruction, to solve problems instead of wishing them away. In other words, it requires a whole new way of looking at space for its own sake rather than that of profit.

If you are an EU citizen, you can sign HouseEurope!’s petition here.

Time is running out to have your gift matched

In this time of unrelenting, often unprecedented cruelty and lawlessness, I’m grateful for Nation readers like you.

So many of you have taken to the streets, organized in your neighborhood and with your union, and showed up at the ballot box to vote for progressive candidates. You’re proving that it is possible—to paraphrase the legendary Patti Smith—to redeem the work of the fools running our government.

And as we head into 2026, I promise that The Nation will fight like never before for justice, humanity, and dignity in these United States.

At a time when most news organizations are either cutting budgets or cozying up to Trump by bringing in right-wing propagandists, The Nation’s writers, editors, copy editors, fact-checkers, and illustrators confront head-on the administration’s deadly abuses of power, blatant corruption, and deconstruction of both government and civil society.

We couldn’t do this crucial work without you.

Through the end of the year, a generous donor is matching all donations to The Nation’s independent journalism up to $75,000. But the end of the year is now only days away.

Time is running out to have your gift doubled. Don’t wait—donate now to ensure that our newsroom has the full $150,000 to start the new year.

Another world really is possible. Together, we can and will win it!

Love and Solidarity,

John Nichols

Executive Editor, The Nation