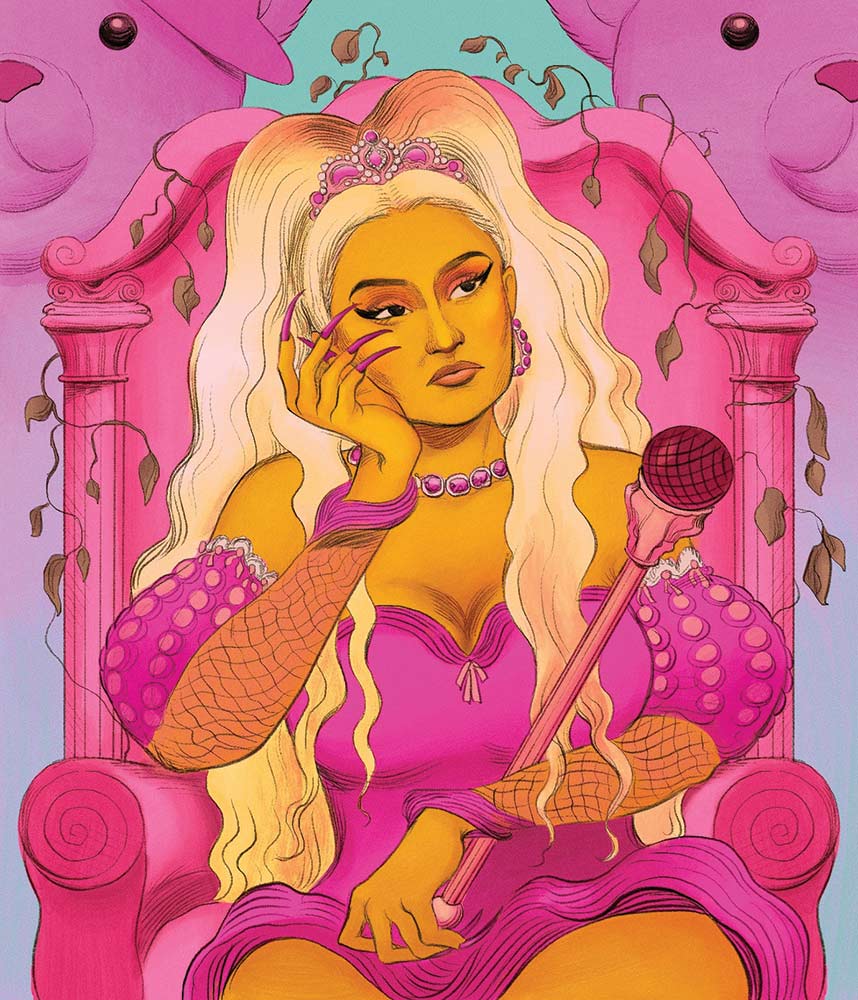

Queen of Rap

The era of Nicki Minaj.

The Era of Nicki Minaj

How the queen of rap revolutionized American music.

We’ve come a long way since the first Pink Friday. Released in 2010, the album cemented Nicki Minaj’s status as one of the brightest stars of her generation of rappers and launched her to global stardom. Pink Friday was also eclectic: It showcased Minaj’s flair for switching up flows, for fun and often funny character work, and above all, it was weird; it sounded like nothing else in the mainstream.

Now, more than a decade later, we finally have an official sequel. In the interim, Nicki put out three studio albums—Pink Friday: Roman Reloaded (2012), The Pinkprint (2014), and Queen (2018)—that confirmed her reputation as the queen of rap and as pop royalty. Pink Friday 2, however, is a little less groundbreaking. It debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard charts, and by all the metrics and numbers you can cite, she’s still on top. And yet it feels like there’s something essential missing from the sequel, something that the numbers can’t measure. There are flashes of the old Nicki here, of course, glimpses of the old brilliance. But the fact that they are there makes the rest of the album feel all the more disappointing, because they remind you what Pink Friday 2 could have been. For better or for worse, the album sounds conventional.

The first thing to note about Pink Friday 2 is the track list: It’s 22 songs, or a formidable one hour and 10 minutes long. Which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, if an album is focused enough.

But I wouldn’t exactly call Pink Friday 2 focused. If there’s a theme, it’s Minaj’s own legacy; the album makes it a point to remind everyone why Nicki is still at the top of the game and the charts, specifically in songs like “Barbie Dangerous” and “FTCU,” which are two of my favorite cuts on this album.

But there’s a bit of tonal whiplash here as well. Going from the sweet, funereal tone of “Are You Gone Already” to the bawdy boasts of “Barbie Dangerous” and “FTCU,” to the menacing “Beep Beep,” and then directly into the love songs “Fallin 4 U” and “Let Me Calm Down” can make the album feel disjointed. We’ve completed an entire emotional arc in six songs, and there are still 16 left to go. It’s a little exhausting.

It’s around this point that the guest verses start piling up. Thankfully, Nicki easily outdoes just about everyone she’s on a track with—from Drake to Lil Wayne to Future—which is an achievement in itself, even though it might also be because the guests sometimes sound half-asleep.

Yet the choice of guest stars is emblematic of the problem with this album as well as the state of rap right now: These are the same people we’ve been listening to for an entire decade, and it feels like everyone is out of ideas. Even Nicki.

Obviously, giving people things that feel familiar is a tried-and-true way to make sales; it’s why film execs are convinced that an endless parade of superhero multiverses is the way to part consumers from their money and to bring about a glorious revival of monoculture. It’s why pop culture writ large can sometimes feel like gray sludge: Everything is similarly focus-grouped and means-tested for maximum likability. The four quadrants rule entertainment, and judging by Pink Friday 2, corporate music isn’t an exception.

There’s a cynicism to Pink Friday 2 that is grating, and it comes out in the sampling. Nine of the 22 tracks feature samples you’ve definitely heard before; Nicki’s grabbing from Cyndi Lauper and the Notorious B.I.G. As Billboard points out, tons of the biggest hits in the past decade have been built on samples. But just because you can afford to build a hit song out of an existing hit song doesn’t mean you should. It can feel like pandering. And here, on Pink Friday 2, it just feels like the same old stuff. It as if Nicki doesn’t trust herself to be different or even weird—you know, like the original Pink Friday a decade and a half ago. To me, the most cynical bit of sampling is on “Super Freaky Girl,” which takes MC Hammer and Rick James as its musical base. It’s a song made for the dance floor, but it feels rote. Like, sure, we’re going to like this—we’ve heard it before!

If it sounds like I’m holding Nicki Minaj to a higher standard than a lot of the other musicians out there today, it’s because I am. She’s at the top of the rap game and has been for quite some time. She’s one of the best rappers alive today. She has climbed the mountain through hard work and maniacal rapping, and God knows she’s allowed to enjoy the view now. But at the same time, there’s no reason for her to put out an album unless she wants to. Pink Friday 2 misses the mark for me because it just doesn’t sound like she’s having fun anymore.

It feels at once overcooked and underthought, something that’s big because it’s got all the aesthetic signifiers of a Big Album. It has the best production and guest stars that money can buy, coupled with the considerable talents of a rapper at the top of her game. But it’s missing the verve and drive that made Pink Friday what it was. It’s missing an essential creative ambition.

Back in 2010, the music press criticized Pink Friday for being more of a pop than a rap album. Over the last decade, it’s become very clear that Nicki was right: She saw what was coming and helped turn rap into pop music in the 2010s. It’s not a stretch to say that Pink Friday was one of the albums that helped create a new mainstream. It was, in a very real sense, a new blueprint. (Sorry, pinkprint.) The problem with Pink Friday 2 is that it sounds like the establishment. It sounds, in other words, just like everything else.

More from The Nation

The Cinema of Societal Collapse The Cinema of Societal Collapse

This year’s Oscar-nominated international feature films—especially The Secret Agent and Sirāt—tackle what it means to live and die under tyranny.

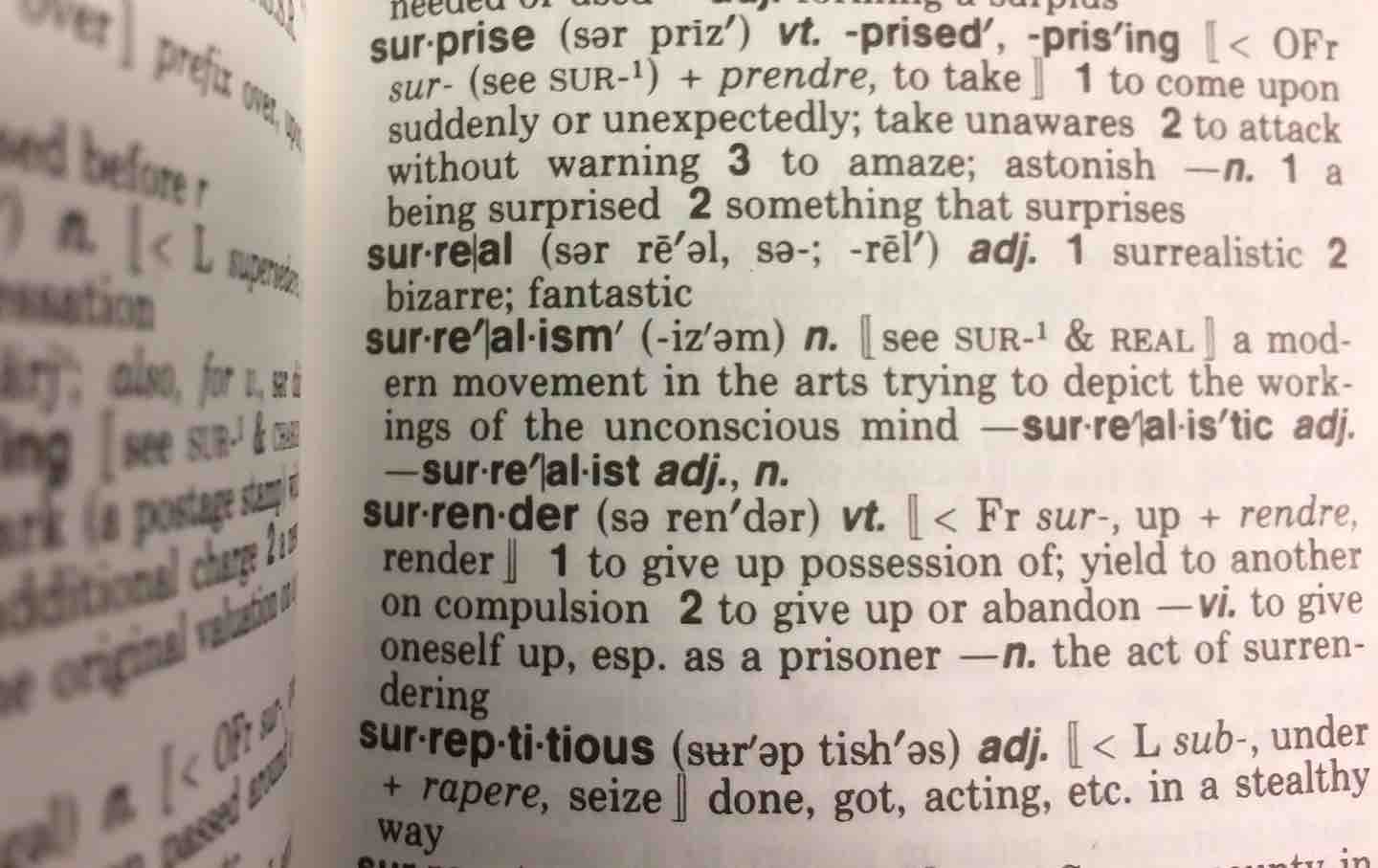

Can the Dictionary Keep Up? Can the Dictionary Keep Up?

In Stefan Fatsis’s capacious, and at times score-settling, personal history of the reference book, he reveals what the dictionary can still tell us about language in modern life

Why We Misunderstand the Chinese Internet Why We Misunderstand the Chinese Internet

Journalist Yi-Ling Liu’s The Wall Dancers traces how the Internet affected daily life in China, showing how similar this corner of the Web is to the one experienced in the West.

The Bad Vibes of “Wuthering Heights” The Bad Vibes of “Wuthering Heights”

Keeping its distance from the novel, Emerald Fennell’s film ends up offering us a mirror of our own times.

Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class? Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class?

Claire Baglin’s bracing On the Clock gives its readers a close look at work behind the fry station, and in the process asks what experiences are missing from mainstream letters.

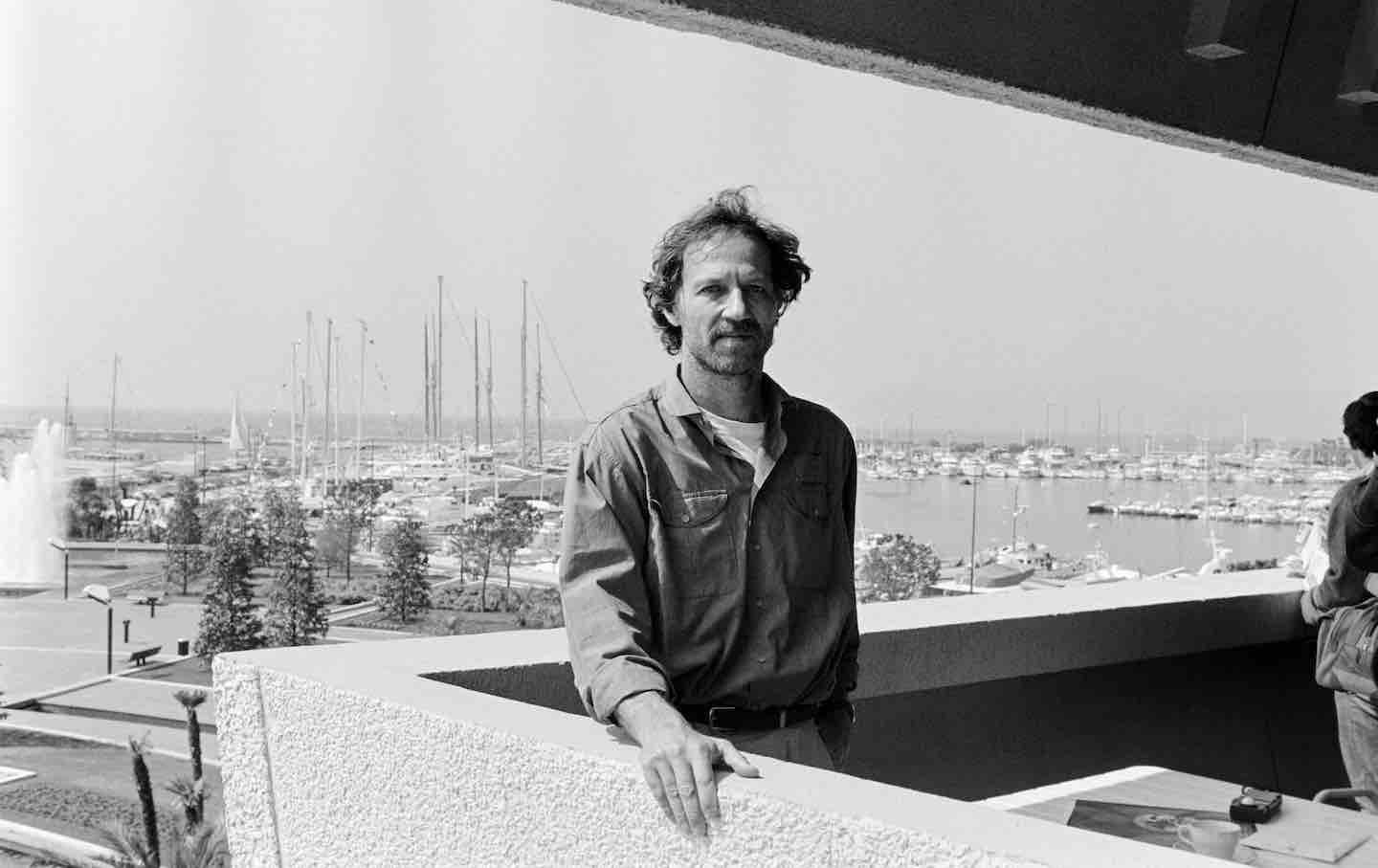

Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction

The German auteur’s recent book presents a strange, idiosyncratic vision of the concept of “truth,” one that defines how he sees the world and his art.