The New Europeans, Trump-Style

Donald Trump is sowing division in the European Union, even as he calls on it to spend more on defense.

The Trump administration’s new National Security Strategy (NSS) depicts a Europe on the brink of collapse. Its malaise, the document stresses, is not just about Russian threats or economic stagnation; rather, Europe risks losing its identity, amid falling birthrates, rising migration, and the alleged silencing of right-wing dissidents. For this, Washington especially blames the European Union, said to “undermine political liberty and sovereignty.” Still, all is not lost. The United States, both “sentimentally attached” to Europe and in need of stable allies, can cultivate “resistance to Europe’s current trajectory within European nations.” Washington draws optimism from the rise of “patriotic”—that is, right-wing—parties around the EU and promises to build up allies in the “healthy nations of Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe.”

Overall, the NSS internalizes Washington’s pivot toward the “Western Hemisphere” as the post–Cold War “unipolar moment” wanes. The EU appears no longer as a crucial base of support for the global hegemon but as a source of regional troubles. As an EU Parliament report on the NSS coyly puts it, “President Donald Trump’s ideological agenda features prominently…notably with respect to Europe.” But the alarm among European leaders betrays a more basic truth: The Trump administration doesn’t even pretend to treat the EU as a peer. The NSS mentions the EU just once, in reference to its “transnational” assault on freedom and sovereignty. If Washington has, historically, supervised the EU integration process, here it openly derides it.

So, if Trump has European allies in “patriotic” parties and certain “healthy nations,” does this mean pushing for the breakup of the EU? A rumored draft of the NSS reportedly spoke of leaning on MAGA’s ideological allies to pull Austria, Hungary, Italy, and Poland out of the bloc. After the EU slapped a $120 million fine on X earlier this month, Elon Musk likewise tweeted a call for the EU to break up. Still, it’s also clear that Washington has huge leverage even without pushing Brexit-style splits. Rising right-wing forces as well as states reluctant to loosen ties with Washington hobble any separate EU initiative. Rather than assume that liberal euro-federalists can pursue their dreams for EU independence, it is crucial to understand how the bloc’s internal divisions, including geographical ones, render it vulnerable to Trump’s policy.

New Europeans

Washington’s interest in exploiting fault lines within the EU isn’t new. Even a quarter-century ago, when the US appeared as a lone superpower, the Bush administration sought to protect this status from European dissent. This conflict flared in the early 2000s, as EU leaders planned both a new European Constitution, and with the accession of a string of new member states in the former Eastern Bloc, from the Baltic down to the Black Sea. While this was a step forward in EU integration, it raised questions over its ability to stand more independently of the United States. The issue crystallized ahead of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, as the Bush administration looked for European accomplices. Tony Blair in Britain, right-wing prime ministers in Italy and Spain, but also all the central-eastern European states about to join the EU, backed Bush’s “coalition of the willing” and sent troops to Iraq.

If the EU’s core powers—France and Germany—tried to assert a distinctly European policy, their autonomous push was undercut by others. Documents like the “Letter of Eight,” signed by the European supporters of the war, or the “Vilnius Letter” from new and aspirant NATO members, expressed a full-throated Atlanticism, rooted in past US support for national movements in the old Eastern Bloc. Radio Free Europe cited pollsters’ findings that, while most Poles opposed the invasion, over half “back[ed] the United States politically in any military action.” US Secretary of State Donald Rumsfeld stressed that such states didn’t want to be led from Paris and Berlin: “You’re thinking of Europe as Germany and France. I don’t. I think that’s ‘old Europe’. If you look at the entire NATO Europe today, the center of gravity is shifting to the East.… you look at vast numbers of other countries in Europe. They’re not with France and Germany, they’re with the United States.”

Today the states that joined the EU in the mid-2000s are no longer “new.” True, few have joined the euro; Poland, easily the biggest by both population and GDP, hasn’t.

Media reporting on elections in Czechia or Romania, or protests in Bulgaria, still routinely resorts to clichés about whether these states will abandon their “European path.” In reality, the fight is more over what kind of Europe. Even nationalists who damn the EU in harsh terms—attacking its immigration policy or its planned phaseout of petrol cars, or painting it as a source of woke dogmas—more rarely issue full-throated calls to quit the EU. Slogans that evoke making the EU a “confederation” or “Europe of nations” instead advocate selective decoupling, hardening borders and reclaiming some national prerogatives, while opposing the Green Deal (a distinctive but now waning pan-EU agenda) and ambitious ideas for an EU army.

Such approaches to changing the EU from within appeal to nationalists in both the “new Europe” and the “old.” They are by now the stock-in-trade of parties like France’s Rassemblement National and Italy’s ruling right wing. This is also an internal fault line on which the Trump administration can play in its concern to keep the EU politically divided. Indicative in this sense is Washington’s clear favoritism toward Viktor Orbán’s government in Hungary, a habitual dissenter in EU politics, over Poland, a much larger state that is far closer to meeting Washington’s nominal priority of getting NATO members to spend 5 percent of GDP on defense. If Polish liberals, sympathetic to Donald Tusk’s ruling coalition, wonder why Trump doesn’t more heartily welcome Poland’s commitment to defense spending, this isn’t the only issue.

Poland

Even insofar as Poland has a proudly “pro-European” government, it illustrates contradictions in the EU. From 2015 to 2023, it was ruled by the hard-right Law and Justice (PiS), whose attacks on the judiciary and habit of siding with Orbán’s Hungary in key votes earned it black-sheep status in Brussels. Yet relations were improved not just after former EU official Tusk replaced PiS’s Mateusz Morawiecki as Polish prime minister in 2023, but already upon the Russian invasion of Ukraine, after which EU decision-makers increasingly credited Poland as a crucial pillar of European defense. Poland is both a relatively large country (only Germany, France, Italy and Spain have bigger populations) and one whose economy has grown much faster than older member-states. Today, Polish GDP per capita is on a par with Italy; last year more migrants moved back to Poland than into Germany.

Far from eternally catching up with the “old Europeans,” leaders in Poland and the Baltic States sometimes today claim to be showing Europe the way forward. This shift today pivots on the EU’s ReArm Europe strategy, with a mooted €800 bn investment in rearmament and, at a more ideological level, the narrative that older EU members are realizing they should have listened to Poles and Lithuanians about the Russian threat. This message was reinforced last month with the destruction, by apparent sabotage, of a stretch of rail track from Warsaw to Lublin, routinely used to deliver European aid to Ukraine. Hailing Tusk’s tough-talking response to the incident, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen stressed the need for European military planning, and credited Poland as the “largest defense spender in Europe.”

Some speculate that such spending could be a form of “military Keynesianism,” and help revitalize the EU economy. Still, Poland points to the limits of this approach, at least currently. For while this country is today NATO’s biggest military spender relative to GDP, its main suppliers are not its own defense industry or other EU member states—relative minnows by this indicator—but the United States and South Korea. Poland is set to be the main beneficiary of the EU’s SAFE (Security Action for Europe) loans plan, meant to boost European procurement. Yet the EU’s reliance on the US for weapons and even energy, and the recent deal for the so-called “Polonization” to in-source the manufacture of Korean tanks, suggest that other European states are hardly the only possible partners.

Nor does the EU offer clear alternative political leadership. It has a nominal foreign-policy chief, in Estonia’s Kaja Kallas, and its leaders often cite the battles waged by pro-EU forces in non-member states like Moldova and Georgia as proof of Europe’s moral authority. Yet, with regard to Ukraine and Gaza, the EU has taken little notable diplomatic initiative, and Trump’s calls for peace talks over Ukraine have repeatedly blindsided European leaders. Faced with this August’s Trump-Putin summit in Alaska, Berlin and Paris pledged to buy more weapons for Kyiv, from Washington, in order to stiffen Trump’s resolve. Yet their initiative remains subordinate to his. Moreover, while efforts to play nice with Trump have often involved British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, more rarely have they drawn on Poland’s Tusk, whose allies complain that other EU leaders cut him out of diplomacy.

Others lean heavier toward Washington. While Tusk’s broad coalition won the 2023 parliamentary elections, this June’s presidential contest handed victory to PiS’s favored candidate, Karol Nawrocki. Among other things, he rode discontent at Polish support for Ukrainians, and in office repeatedly blocked legislation extending welfare benefits for Ukrainian refugees in Poland—eventually caving, albeit insisting he would not allow any further extension. Yet he, like Tusk, also strongly favors a stronger US military presence in his country. Tusk’s own foreign minister, Radosław Sikorski—hardly a fan of Trump—even mooted, during Nawrocki’s visit to Washington in September, that the new Polish president’s relations with MAGA could pay off, if Washington boosted US troop numbers in his country. As against ideas of European “strategic autonomy,” perhaps led from Paris or Berlin, Sikorski has emphasized a pragmatic “strategic harmony” where Europe becomes more self-reliant, yet closely allied to the United States.

Independent Europe?

So, is the EU merely a victim in all this, or does it have opportunities to forge ahead? The end of the war in Ukraine may be far off, but could be decisive for Europe’s future. It is reportedly suggested, as part of the Trump administration’s current 20-point draft peace plan, that Ukraine would join the EU in 2027. In truth, the idea of integrating such a large and relatively poor state, far faster than any previous member has been allowed to join, is hardly likely to achieve the needed unanimous agreement across the EU. The fact that the Trump administration would even suggest this—seemingly without consulting European leaders themselves—points to Washington’s interest in having Europe absorb the social and human costs of the conflict, even without its having a real say in the outcome.

For some of the most enthusiastic supporters of EU integration, including British liberals who now find themselves outside the bloc, all this shows the need for the EU to finally assert its independence. The conclusion, from the NSS report, that the Trump administration is ideologically hostile to the EU comforts the idea, voiced by historian Timothy Garton Ash, that Europe must band together to avoid a peace deal imposed over the heads of both Ukrainians and European leaders. Where Trump may try a classical imperial carve-up, such authors argue, EU members and “like-minded states” like Britain or Canada need the “strategic determination” and “fighting spirit” to help Ukraine resist, even if their American former patron tries to force Volodymyr Zelenskyy to swallow a bad deal.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Garton Ash admits many weaknesses in the EU, yet concludes that this is ultimately a question of willpower. Europe’s weaknesses here sound like a demand for greater unity. The eventual integration of Ukraine into the EU, Garton Ash suggests, would be a fitting riposte to imperialist visions in Washington and Moscow. Yet both the alarmist prospect of the EU breaking up and the idealist vision of EU federalism galvanized by Trump’s hostility, appear overstated. Current trends in the bloc, including the policies advocated by rising hard-right forces, instead point to a more partial outcome: EU-funded investment that would allow member-states to build up their armed forces, mount new infrastructure projects, and take measures, as well, like reintroducing national service, but without arriving at a cross-EU military command, a more integrated political leadership, or a really joint diplomatic approach.

The Trump administration remains unpopular among most European populations, and even MAGA’s ideological allies often chafe against the idea that they are subordinate to an American “big brother.” Yet, it seems unlikely that dislike of Trump will be enough to galvanize Europeans behind a coherent alternative foreign policy, or indeed that—almost four years into the war in Ukraine—the EU’s current heads of government can rally as-yet-untapped reserves of “fighting spirit” among the population. Troublingly, not only Orbán’s Hungarian government but also a rising force like Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland favor reindustrialization based on rearmament precisely on condition that it is not tied to support for Kyiv. To the idea that Ukraine is fighting to defend all of Europe, they reply that Europe needs to defend itself from Muslims and Africans.

The Trump administration is no all-powerful actor able to remold EU politics at will. Yet it is well able to exploit old fault lines within EU politics, and the lack of truly collective “willpower” that the most EU-federalist forces hanker after. For want of real independence from Washington, today’s EU leaders instead combine their forces in the attempt to convince Trump that they are really his allies after all. They, like the New Europeans of yesteryear, champion Atlanticism for fear that isolationist US Republicans may fail to stand with them. Back in the days of the Bush administration, some in the EU resisted the US’s claim to reshape the world by its own rules. Today, faced with Trump’s concessions to Russia, many of the same capitals seem keen to maintain the unipolar moment that once was.

More from The Nation

There Is No “After Gaza” There Is No “After Gaza”

Whether intentionally or with callous word choice, too many have begun relegating Palestine to the past tense.

Cuba Rallies Residents, Prepares for War Cuba Rallies Residents, Prepares for War

As Washington escalates regime-change pressure after the Venezuela raid, Cuba braces for confrontation amid economic collapse, oil shortages, and mass mobilization.

Jared Kushner’s “Plan” for Gaza Is an Abomination Jared Kushner’s “Plan” for Gaza Is an Abomination

Kushner is pitching a “new,” gleaming resort hub. But scratch the surface, and you find nothing less than a blueprint for ethnic cleansing.

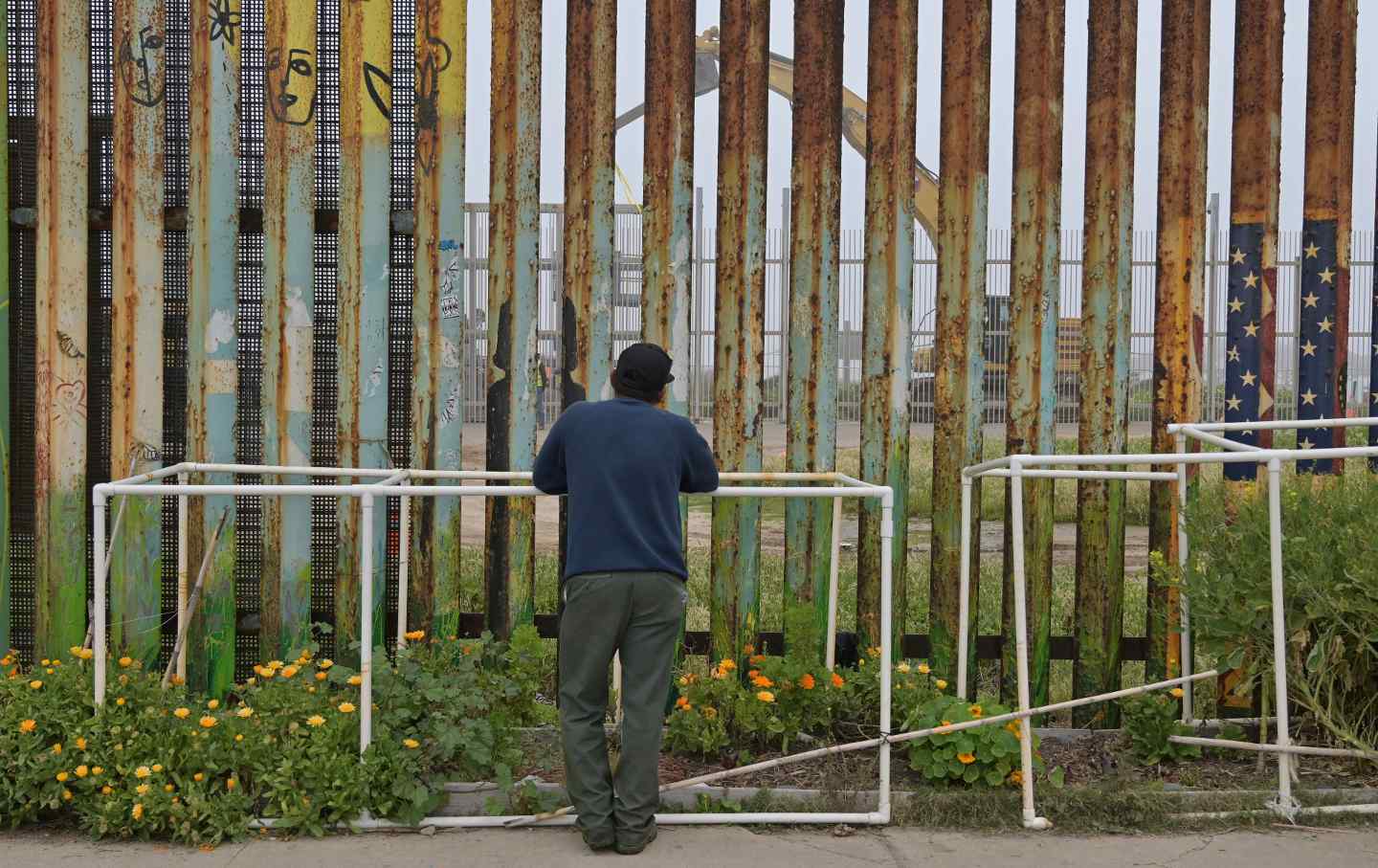

I’ve Covered Migration and Borders for Years. This Is What I’ve Learned. I’ve Covered Migration and Borders for Years. This Is What I’ve Learned.

Borders are both crime scenes and crimes, with nationalism the motive.

Gaza Is a Crime Scene, Not a Real Estate Opportunity Gaza Is a Crime Scene, Not a Real Estate Opportunity

The Trump administration’s plan for a New Gaza has nothing to do with peace and rebuilding, and everything to do with erasure.