Jonathan Glazer on Gaza and the Holocaust

Jewish self-defense or universal rights?

Accepting the Oscars awarded to his film The Zone of Interest, Jonathan Glazer said, referring to the colleagues who joined him on stage, “We stand here as men who refute their Jewishness and the Holocaust being hijacked by an occupation, which has led to conflict for so many innocent people. Whether the victims of October the 7th in Israel or the ongoing attack on Gaza, all [are] victims of this dehumanization.” This remark sparked heated accusations. In a March 11 open letter to Glazer, the chairman of the Holocaust Survivor’s Foundation USA (HSF), David Schaecter, wrote: “You should be ashamed of yourself for using Auschwitz to criticize Israel.” Anti-Defamation League CEO Jonathan Greenblatt responded, “Israel is not hijacking anyone’s Jewishness. It’s defending every Jew’s right to exist.”

These are just two examples of how Israel’s defenders treat charges that Israel has committed war crimes or worse in its campaign in Gaza as “misappropriation” or “minimization” of the Holocaust. During the UN General Assembly debate of November 26, 1947, on the resolution to partition Palestine, the representative of Uruguay asked rhetorically, “Why is it necessary that there should be a Jewish State?” In his answer he said,

What a burden of suffering [the Jewish people] have borne! No one in our day has endured such a burden. Nazism came and inaugurated a regime, not merely of racial persecution, but of racial extermination … the concentration camps, the gas chambers, the crematoria, claiming four million victims, sacrificed alive.

But the founding of the State of Israel was not the sole international response to the Holocaust. At least equally important was the codification in international law of the crimes that constituted the Holocaust, including war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. And as Philippe Sands shows in his book East West Street, the intellectual authors of these concepts were Hersch Lauterpacht and Rafael Lemkin, two Jewish legal scholars educated in Lviv, now in Ukraine. Lauterpacht, Lemkin, and the maternal grandfather of Sands all grew up in Wołkowysk, a village near Lviv. Their many relatives who remained there were all killed by the Nazis.

In the summer of 1944, at Cambridge University, Lauterpacht drafted the statute for the Nuremberg tribunal in consultation with the tribunal’s lead prosecutor, Robert H. Jackson. The statute defined war crimes to “include, but not be limited to, murder, ill-treatment or deportation…of civilian population of or in occupied territory, murder or ill-treatment of prisoners of war, killing of hostages, plunder of public or private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity.”

Lauterpacht also persuaded Jackson to include in the Nuremberg statute a new concept he had developed, “crimes against humanity.” Those included “murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war, or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds in execution of or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal.”

Lauterpacht focused on preventing and punishing crimes against individuals. Lemkin, however, in a book published in 1944 while he was at Columbia University, coined the word “genocide,” to designate the destruction of groups. In December 1946 the UN General Assembly affirmed that “genocide is a crime under international law.” In 1948 the General Assembly adopted Lemkin’s proposal for a “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.”

As Sands shows, Lemkin “made clear that he was concerned with the destruction of any group, not just Jews…. To stress ‘only the Jewish aspect’ would offer an invitation for genocide defendants ‘to use the court for anti-Semitic propaganda.’ The charge of genocide had to be part of a broader strategy, to show its perpetrators as enemies of mankind, a ‘specially dangerous crime.’”

War crimes and crimes against humanity were also codified in the Geneva conventions of 1949 and three subsequent optional protocols.

On January 26, 2024, the International Court of Justice, also founded after World War II in accord with the Charter of the United Nations, ruled in response to a petition by South Africa that there is “plausible” evidence that in Gaza Israel has committed acts of genocide as defined by the Convention: “killing, causing serious bodily and mental harm, inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part, and imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.”

The court also ruled that “the intentional failure of the Government of Israel to condemn, prevent and punish…genocidal incitement constitutes in itself a grave violation of the Genocide Convention.” The court cited statements of a multitude of Israeli officials, from the Prime Minister and President on down, as evidence of “intent” to destroy the Palestinians of Gaza “in whole or in part.”

The International Criminal Court, which has jurisdiction over war crimes and crimes against humanity, has yet to rule on Israel’s actions in Gaza, but the daily deluge of videos and testimonies of killings, plunder, “wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages,” attacks on the food supply, health care personnel, patients, journalists, teachers, professors, schools, and universities; the public humiliation of prisoners; and the publicly announced plan to displace over a million already displaced Gazans to a yet-unknown destination, make it more than “plausible” that Israel is committing war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Lauterpacht and Lemkin developed fundamental components of international humanitarian law while in refuge in Britain and the United States, even as they had no news of what had happened to the families they had left behind. In Nuremberg they tried—Lauterpacht from the inside and Lemkin from the outside—to shape the cases against Nazi officials accused of the crimes that were engulfing their families.

As the trials approached their end, in the summer of 1945, a trickle of survivors from the East brought tales of the fates of those left behind. In September 1945, Lemkin learned that his parents, Bella and Jozef, had been deported to the Treblinka extermination camp. Early in 1946 Lauterpacht received a letter informing him that his family’s only survivor was his niece Inka, who had made it to Palestine.

Sands’ grandfather died in 1997 without learning what had happened to his family. Only in 2010, during a visit to Wołkowysk, did Sands learn that on March 25, 1943, German soldiers in the village had rounded up 3,500 Jews including about 70 of his grandfather’s relatives, marched them into the woods, shot them, and left their bodies in sand pits.

Sands became an internationally renowned legal scholar and author, based at University College London. As a prominent scholar and practitioner of international humanitarian law, he has worked on cases on the former Yugoslavia, the Congo, Libya, Afghanistan, Chechnya, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Sierra Leone, Guantánamo, and Iraq.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →On February 19, 2024, Sands stood before the bench of the International Court of Justice in the Hague as the representative of the State of Palestine, challenging the legality of Israel’s occupation of the territories captured in 1967.

Sands concluded his intervention saying that “The occupation is illegal and must be brought to an immediate unconditional and total end,” and that “all UN members are obliged by law to end Israel’s presence on the territory of Palestine.” The court has confirmed, he added, that “the Palestinian people have a right to self-determination…which is not and can never be a matter of negotiation.”

Sands did not note, nor did he need to, that neither the genocide convention nor any other provision of international law grants an exemption from accountability to victims of past crimes or to those fighting others who have committed such crimes. When the Holocaust is used to justify defiance of humanitarian law, it is indeed being “hijacked,” just as Glazer said. Seeking to enforce provisions of international law that were enacted to prevent events like the Holocaust is an appropriate way to honor its memory.

Can we count on you?

In the coming election, the fate of our democracy and fundamental civil rights are on the ballot. The conservative architects of Project 2025 are scheming to institutionalize Donald Trump’s authoritarian vision across all levels of government if he should win.

We’ve already seen events that fill us with both dread and cautious optimism—throughout it all, The Nation has been a bulwark against misinformation and an advocate for bold, principled perspectives. Our dedicated writers have sat down with Kamala Harris and Bernie Sanders for interviews, unpacked the shallow right-wing populist appeals of J.D. Vance, and debated the pathway for a Democratic victory in November.

Stories like these and the one you just read are vital at this critical juncture in our country’s history. Now more than ever, we need clear-eyed and deeply reported independent journalism to make sense of the headlines and sort fact from fiction. Donate today and join our 160-year legacy of speaking truth to power and uplifting the voices of grassroots advocates.

Throughout 2024 and what is likely the defining election of our lifetimes, we need your support to continue publishing the insightful journalism you rely on.

Thank you,

The Editors of The Nation

More from The Nation

Women Are Leading the Resistance Against Executions in Iran Women Are Leading the Resistance Against Executions in Iran

Their prominence in the ongoing struggle for human rights has been met with fierce crackdowns by the state.

The Party Promising Kashmiri Statehood Wins an Election The Party Promising Kashmiri Statehood Wins an Election

In the first vote since India revoked the statehood status of Jammu and Kashmir, the National Conference party emerged with the most seats in the Legislative Assembly.

“The Israeli Army Martyred My Father”: What Gaza's Journalists Have Endured “The Israeli Army Martyred My Father”: What Gaza's Journalists Have Endured

Three Palestinian journalists describe what it is like to report from the middle of a genocide.

Israel Is Killing Whole Families in Gaza—With Weapons Made in America Israel Is Killing Whole Families in Gaza—With Weapons Made in America

Five-year old Hind Rajab was the victim of a bomb manufactured in Iowa. Months later, the Biden administration is still sending weapons.

The New Cold War in the Pacific Is Dangerously Close to Heating Up The New Cold War in the Pacific Is Dangerously Close to Heating Up

Bristling with armaments and seemingly strong, the current ad hoc Western coalition may yet prove, like NATO, vulnerable to sudden setbacks from rising partisan pressure...

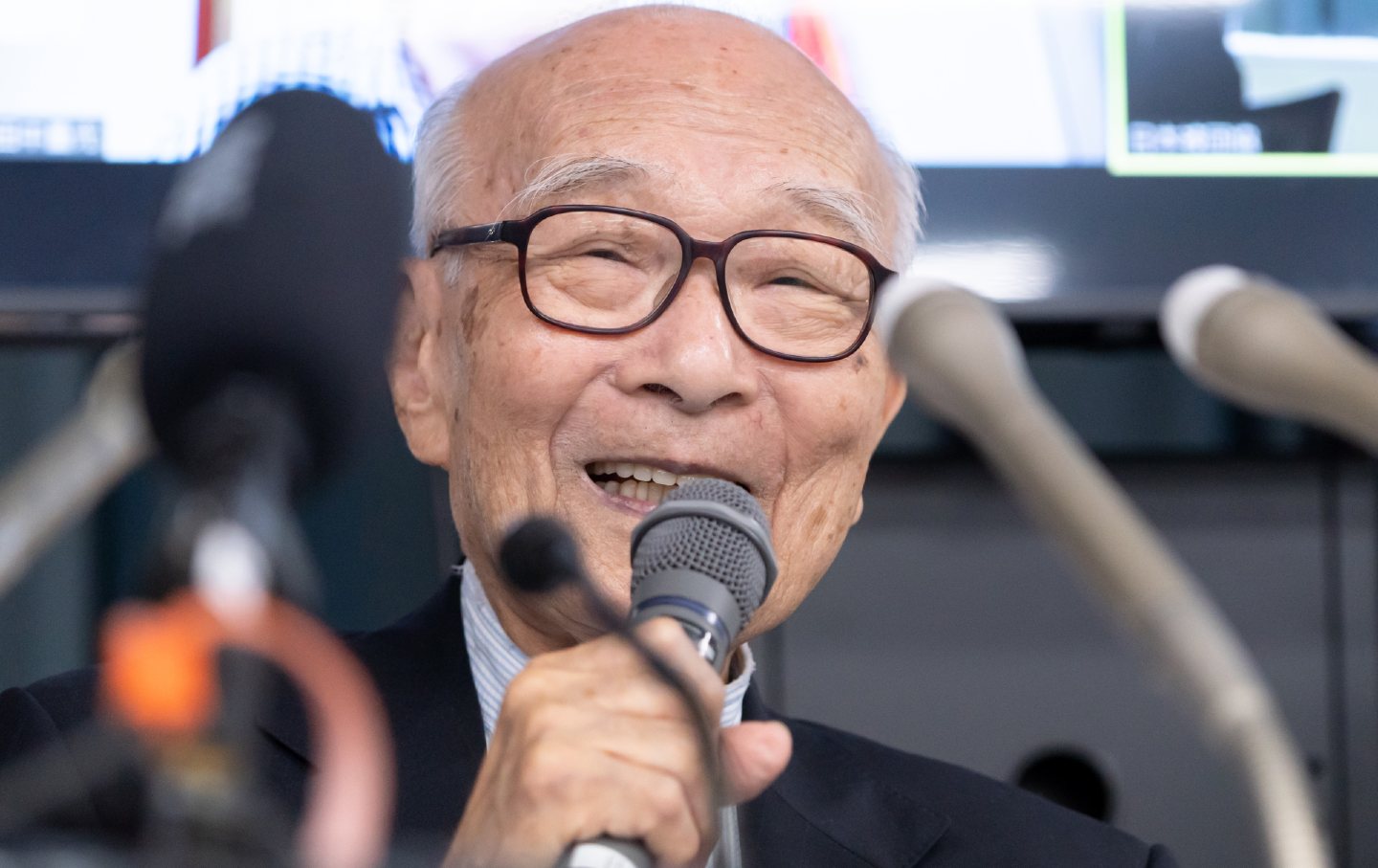

Nihon Hidankyo’s Bittersweet Receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize Nihon Hidankyo’s Bittersweet Receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize

The prize is a reminder that we must abolish and eliminate nuclear weapons.