What Edward Said Teaches Us About Gaza

On Palestine and the geography of vanishing.

This piece is part of A Day for Gaza, an initiative in which The Nation has turned over its website exclusively to voices from the Gaza Strip. You can find all of the work in the series here.

Ihave lived long enough with Gaza to know that it refuses to hold still. It recedes and insists in the same breath, a place continually pulled away and continually reasserted, as if caught in a struggle between erasure and endurance. Streets are redrawn, renamed, obliterated, and then remembered in whispers that rise like breath in the night. A path I once took toward the sea now halts abruptly in rubble or is swallowed by dunes that devour the horizon. A neighborhood once alive with the fragrance of jasmine in its courtyards has been pushed into the realm of memory, spoken of only in the past tense, its reality surviving only in language while banished from the ground itself.

Gaza does not vanish in a single strike that history can date and seal. It diminishes gradually, faltering and splintering under daily attrition, yet it persists with the stubborn rhythm of those who remain. To walk here is to step into a geography of vanishing, a terrain where disappearance is not an event that ends but a condition that settles into every gesture and every breath, making survival itself feel like a form of unfinished writing, lines drawn on a page that will never be complete.

A Day for Gaza

-

A Ceasefire in Name Only

-

The Gaza Street That Refuses to Die

-

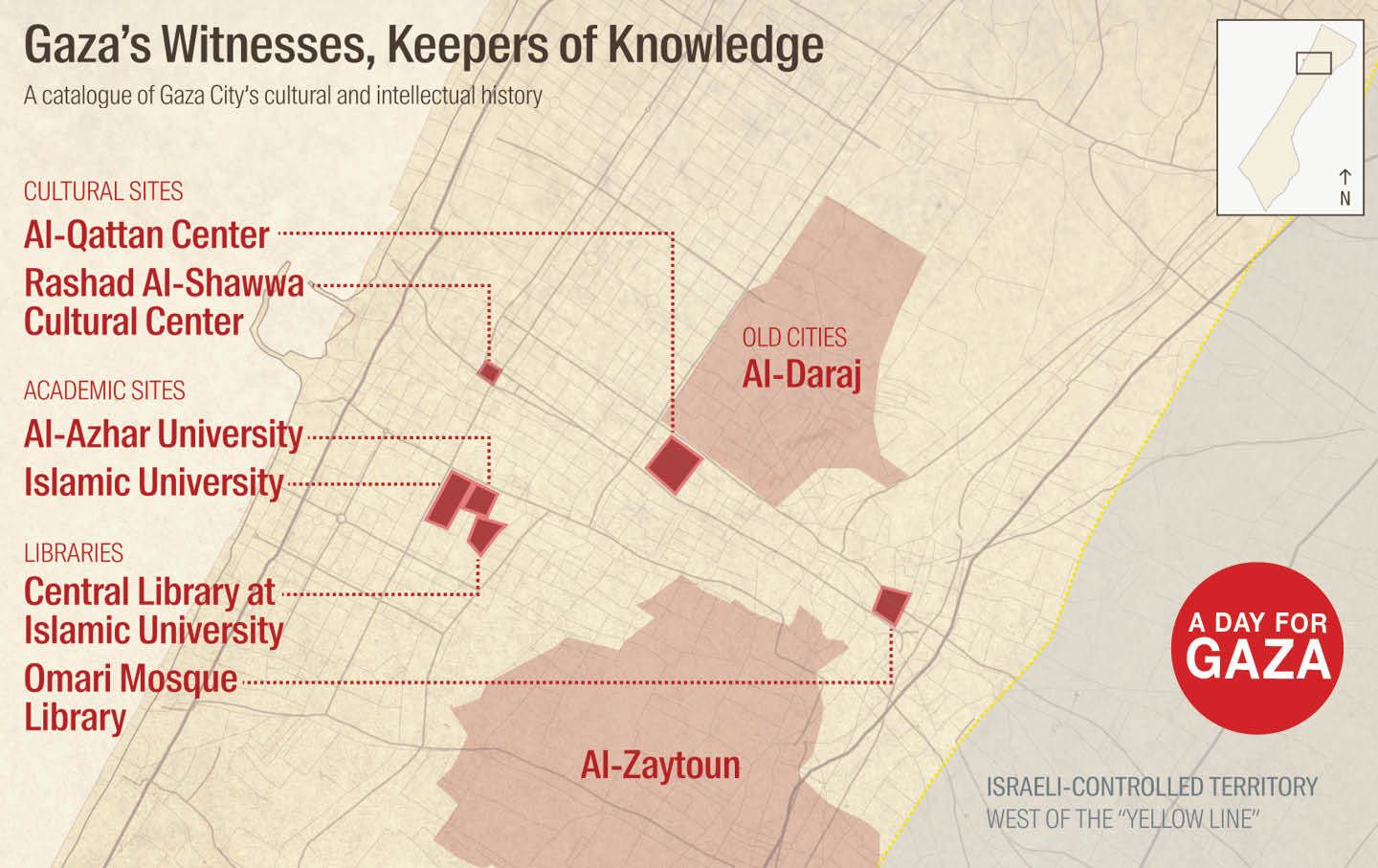

A Catalog of Gaza’s Loss

-

My Sister’s Death Still Echoes Inside Me

-

What Gaza’s Photographers Have Seen

-

How to Survive in a House Without Walls

-

What Edward Said Teaches Us About Gaza

-

What Happens to the Educators When the Schools Have Been Destroyed?

-

At the Doorstep of Tomorrow

-

“We Have Covered Events No Human Can Bear”

Displacement is the force that shapes this geography. It presses against every door and every silence, reshaping the city even as its ruins remain. From the beginning of the war, waves of evacuation swept through Gaza, driving families from the north toward the south. At first many believed that the ordeal might be temporary, that days or weeks would pass and they would walk back to homes left waiting for them. Yet the days became months, and the rhythm of departure became the new grammar of life. Entire neighborhoods were emptied, belongings bundled into sacks or left behind altogether, and the roads south thickened with the dust of unchosen journeys.

Now the nightmare circles back with sharper cruelty. New horrors demand new departures, and families that once believed they might return move again with the terrible knowledge that they will not. There is no longer even the faintest possibility of homecoming. Displacement is no longer the pause of exile but the permanence of loss, a repetition that engraves absence more deeply with every mile walked away from the north.

Edward Said, one of the bards of our dispossession, comes back to me in these moments, offering words to frame this condition. He wrote with clarity about the way exile reshapes consciousness, stretches it across fracture and compels one to hear conflicting scores without forcing them into harmony. In Gaza, exile is not a metaphor or an intellectual category; it is the road south that families tread again and again. Life continues in fragments that carry the weight of rupture. A prayer whispered in a makeshift tent, bread baked in a stranger’s kitchen with borrowed fire, a name spoken aloud even when the street it belonged to has been lost. These small acts are heavy with exile, because they are performed away from the places where they first belonged.

In these last weeks, that inheritance has taken on a sharper, more immediate shape. Exile is no longer a word I meet in books or at borders; it is what I hear in every call I receive. Friends send voice notes from the edges of the Strip, their sentences frayed by the distant thud of shelling that has only shifted a few kilometers away. They speak of tents pulled tighter against the cold, of children drawing remembered houses into sand and dust, of aid trucks edging through streets that no longer know whether to greet them or grieve what they confirm has been lost. In their voices there is no clear “after,” only a long, uneven “during” that stretches from one day to the next without any promise of an end.

Said’s collaboration with Jean Mohr, After the Last Sky, speaks to this fracture, refusing to allow photographs and prose to coalesce into a single, seamless account. Images and fragments of text sit beside one another in tension, like voices that acknowledge each other but refuse to merge. One photograph lingers in my mind: Nazareth seen from the heights of a Jewish settlement, the city below rendered in pale limestone, visible yet withheld. The vantage point denies intimacy. It forces the viewer to recognize how occupation infiltrates even the act of looking, how vision itself becomes colonized. What appears to be a panorama promising wholeness reveals itself as a carefully framed absence, a composition trembling with what is missing.

When I walk through Gaza’s fractured neighborhoods, I hear the echo of that image. Yet now the absence is amplified by the silence of those displaced, by streets no longer emptied only by destruction but by the departure of those who once filled them. The incompleteness of the image is no longer only in the ruins; it is also in the missing voices, the laughter and quarrels carried away on roads of exile.

In such a landscape, narration becomes fragile, almost unbearable in its incompleteness. Said once asked who has “permission to narrate,” and in Gaza the question returns with particular sharpness. Speech arises in fragments, carried not through proclamations but through gestures. A grandmother whispers the name of a vanished street to her granddaughter, as though holding it in her mouth could shield it from disappearance. A child draws the outline of a demolished house, tracing the shape of memory onto paper with the hope that the image might resist oblivion. A threshold remains standing, its doorway intact though the rooms behind it have collapsed, silent testimony that the idea of shelter can outlive the destruction of its walls. Yet displacement distorts even these fragments. The grandmother whispers the name not at the site of the street but in a shelter far to the south. The child draws a house that will never be reached again. The threshold is left to weather alone, its guardians gone forever. Narration becomes the act of carrying fragments into exile, keeping them alive even when they no longer belong to the ground beneath one’s feet.

To read Gaza contrapuntally is to listen to these rhythms that refuse to merge. The language of administration speaks of “zones” and “targets,” while bodies remember pathways to school, the corners of markets, the rhythm of evening walks. Maps are rewritten with new lines, while memory clings to a grapevine shading a courtyard. Security rhetoric overlays itself on the scent of bread rising under cloth. And displacement thickens this dissonance. The market is recalled by those who no longer stand in it, the courtyard evoked in memory because the vine cannot be reached, the bread baked in kitchens that do not belong to the families who knead it.

Contrapuntal reading in Gaza means attending to the fractures between presence and absence, between those who remain among ruins and those who are carried away, between the home that once stood and the exile that now speaks for it. Said’s writings on lateness illuminate this condition further. He found dignity in incompletion, in works that refused to resolve fracture into harmony. Late style, he argued, carries tension forward without resolution. To write in that style is to allow sentences to hold contradiction, to let paragraphs stretch without reaching final cadence. In Gaza, lateness is not a literary strategy but a condition of life. The city is held perpetually open by violence, yet filled with lives that insist on continuing. To be uprooted repeatedly is to live in a state that cannot close, to carry existence in temporary shelters, to live with belongings half-packed and half-abandoned, never sure which walls will hold and which will fall. To describe Gaza honestly is to accept that the narrative will remain unsettled, heavy with the weight of exile, stretched between what has been lost and what refuses to die.

The so-called ceasefire has not delivered an ending, only another version of this lateness. People speak of it without conviction, as if tasting a word that does not match the air around them. There are no clear thresholds to step across, no morning when someone can say: now the war has finished. Instead, life continues in a series of suspended scenes: tents that were meant to be temporary growing roots in the mud, schoolyards that will not return to lessons, hospital corridors that still smell of smoke. Gaza remains held open, its story dragged forward without closure.

And yet the danger of spectacle shadows every attempt to write. Said warned us against this temptation to transform wreckage into an aesthetic image, to arrange ruins into tragic theater for distant audience. What rescues writing from this trap is a fidelity to the ordinary. There are details that persist even in exile: a pot of tea poured at dusk in a crowded shelter, a grandmother’s story retold in a classroom improvised between partitions, children quarreling over scraps of space, dough rising in a bowl though the oven belongs to another household. These are proof of continuity, their weight felt precisely because they endure in exile as much as at home.

To write Gaza through Said is not to pour its pain into theory or to cloak its endurance with borrowed grandeur. It is to listen carefully and humbly to silence, to fragments, to interruptions, and to gestures that refuse to be extinguished. It is to allow incompletion to remain visible, to resist coherence that the city itself has been denied. Gaza does not yield one story that can be polished into final form; it asks to be remembered in its dissonance, in sentences that twist and falter, in paragraphs that stretch while leaving space for what cannot be uttered. Its geography is one of vanishing, but vanishing here is inseparable from displacement. Presence recedes not only in ruins but in exile, in the endless departures that empty houses and fill roads with the weight of footsteps that will not turn back.

When I walk along streets that no longer lead to any home, I feel the paradox press against me with the force of both wound and endurance. Gaza continues to exist in ways that maps cannot record, in lives that persist against erasure, in memories carried southward or abroad.

Displacement has stretched the geography of vanishing beyond the city itself, scattering fragments into tents, checkpoints, and border crossings. I left Gaza, and in leaving I carried with me what would not resolve into narrative, pieces of a city that no longer fits together. Writing is the only way I know to keep them audible, to allow the fragments to speak even in exile. If they endure, it will be because they are carried not as finished stories but as burdens that remain alive: heavy, unfinished, and unyielding.

Now, in what the world calls a fragile ceasefire, I read and reread these fragments knowing that nothing essential has changed. The city is still in pieces. The shelling only shifted to the edges, as if the violence were pausing for breath rather than ending, while people remain in tents that were never meant to hold a life, let alone a whole winter. The word “ceasefire” arrives faster than medicine or rebuilding material; it appears in statements and on screens, but not in the streets.

Gaza’s vanishing is still unfolding in the present tense—and even in this broken pause the city keeps sending out faint but steady signals of life, asking to be witnessed rather than buried.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

How to Survive in a House Without Walls How to Survive in a House Without Walls

After their home was obliterated, Rasha Abou Jalal and her family remain determined to build a new one, even if it must be built out of nothing.

A Day for Gaza A Day for Gaza

Today, The Nation is turning over its website exclusively to stories from Gaza and its people. This is why.

What Happens to the Educators When the Schools Have Been Destroyed? What Happens to the Educators When the Schools Have Been Destroyed?

Hamada Abu Layla spent 22 years earning three degrees from Gaza universities. Now they mock him from a garbage dump.

My Sister’s Death Still Echoes Inside Me My Sister’s Death Still Echoes Inside Me

Rewaa was killed by an Israeli bomb. Her absence has broken me in ways I still cannot describe.

“We Have Covered Events No Human Can Bear” “We Have Covered Events No Human Can Bear”

Journalists in Gaza have bartered their lives to tell a truth that much of the world still doesn’t want to hear.

A Catalog of Gaza’s Loss A Catalog of Gaza’s Loss

Recording what has been erased—and making sense of what remains.