Mark Bittman writes the way he cooks: The ingredients are wholesome, the preparation elegantly simple, the results nourishing in the best sense of the word. He never strains; there’s no effort to impress, but you come away full, satisfied, invigorated.

From his magnum opus, How to Cook Everything, and its many cookbook companions, to his recipes for The New York Times, to his essays on food policy, Bittman has developed a breeziness that masks the weight of the politics and economics that surround the making and consuming of food. In Animal, Vegetable, Junk, his latest book, he offers us his most thoroughgoing attack on the corporate forces that govern our food, tracking the evolution of cultivation and consumption from primordial to modern times and developing what is arguably his most radical and forthright argument yet about how to address our contemporary food cultures’ many ills. But it still goes down easy; the broccoli tastes good enough that you’ll happily go for seconds.

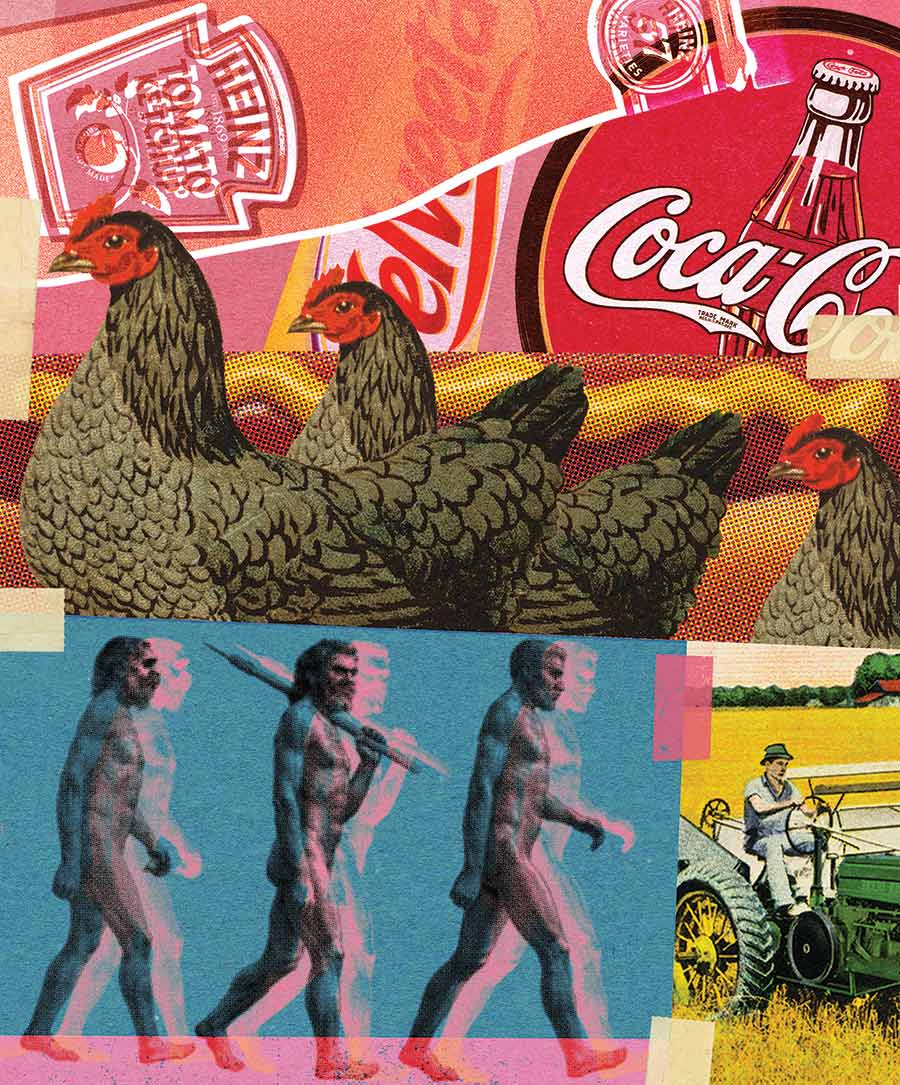

Bittman starts Animal, Vegetable, Junk with the early hominins. As these human ancestors learned to walk upright, they began to forage across larger areas and hunt with comparative ease. Bittman notes that they also started to develop more flexible diets: “a variety of fruits, leaves, nuts, and animals, including insects, birds, mollusks, crustaceans, turtles, small animals…rabbits, and fish.” Eventually, with the nutritional boost of this new diet, they soon learned how to track faster prey (which was easier to do in groups and thus produced more social behavior) and to cook over fire.

With more nutrients and more advanced methods of gathering and cooking food, the early hominins’ “already sizeable brains grew bigger.” Hardwired to eat “what we can, when we can,” they had diets that differed from place to place: “Some humans had diets high in fat and protein, and some had diets in which carbohydrates dominated.” But despite these differences, the emerging food cultures and diets had one thing in common. The epoch of hunting and gathering produced “a period of greater longevity and general health than in almost any other time before or since.” Eventually it also produced a new trick: how to stay in one place and grow crops whose surplus could be stored.

That transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture was welcome in many ways, but it came at a price, Bittman writes. Yes, it supported larger populations, but diets became monotonous and less nutritious, life spans declined, and work hours increased. Bittman is not the first to make this argument. Jared Diamond memorably called farming the biggest mistake in human history, and so Bittman doesn’t belabor the point, accepting that we now live on a planet where food is something we raise, not something we hunt or gather.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

For Bittman, the central drama of this story begins in the course of the last century, as agriculture and food processing became mass industries, and as we moved from having two types of food (plants and animals) to being overwhelmed by a new third type—one that was “more akin to poison.” These “engineered edible substances, barely recognizable as products of the earth, are commonly called ‘junk.’ ”

This junk food has created, Bittman argues, a “public health crisis that diminishes the lives of perhaps half of all humans.” Through its dependence on an agriculture that “concentrates on maximizing the yield of the most profitable crops,” it has done “more damage to the earth than strip mining, urbanization, even fossil fuel extraction.”

Any number of data points illustrate this new reality, but let’s choose a couple that show what happened to farming. In the decades since World War II, chicken production has increased by more than 1,400 percent—while the number of farms producing those birds has fallen by 98 percent. This kind of industrialization is obviously unkind to animals and to those who once raised them—the former live in tiny cages, and the latter, depending on where in the world they reside, often move to shantytowns on the edges of capital cities. And the damage to the natural world is every bit as great. In Iowa, for instance, stock living in CAFOs, or concentrated animal feeding operations, produce as much waste as 168 million people, or 53 times the state’s population. This manure is housed in giant lagoons that sometimes flood; it is perhaps not surprising that the largest municipal water treatment plant in the world is required to allow the people of Des Moines to drink the tap water.

The ability to produce massive quantities of a few commodities—wheat, corn, and corn syrup—has enriched not farmers but a few giant middlemen (companies like Archer-Daniels-Midland and Cargill) and implement dealers (John Deere makes four times as much money providing credit to struggling farmers as it does selling tractors). And it has created a new problem: what to do with the massive amount of calories that this commodity-focused agriculture produces. “The system,” Bittman explains, now “delivers a nearly uninterruptible stream of food, regardless of season,” and in the process it has created junk: the processed food that now dominates the Western diet and, increasingly, many other diets around the world. “Junk made it possible to encourage people to—really, [made] it difficult for them not to—eat too much non-nourishing food over a prolonged period.”

As Bittman notes, the calories have to go somewhere, and—thanks in no small part to the advertising industry, which attached itself to the food industry like a remora to a shark—they went inside us; we look the way we do because of the need for the Krafts and Heinzes of the world to keep their profit margins growing by finding new ways to get us to consume their limited line of basic commodities. “Global sugar consumption has nearly tripled in the past half-century,” he writes, and so has obesity; the number of people worldwide living with diabetes has quadrupled since 1980. “Two thirds of the world’s population,” Bittman tells us, “lives in countries where more people die from diseases linked to being overweight than ones linked to being underweight.”

It’s not just our bodies that suffer from this commodity agriculture; it does huge damage to communities as well. Bittman discusses how small Black farmers, especially in the South, have been systematically sidelined by federal policy and how a fairly stable system of peasant agriculture in Mexico was destroyed by the North American Free Trade Agreement, which dismantled the economic protections that allowed it to persist and flooded the country with cheap American grain. Since it took 17.8 labor days to produce a ton of corn in Mexico, and 1.2 hours to do it on industrialized farms in the American Midwest, the result was never in doubt. Now the United States supplies Mexico with 42 percent of its food, which should give you some idea of why so many people needed to come north. Adds Bittman: “NAFTA also brought junk food to Mexico. Imports of high-fructose corn syrup increased by almost 900 times, and soda consumption nearly doubled,” making Mexico the world’s fourth largest per capita consumer of soda. It also now “leads the world’s populous nations in obesity, and diabetes—almost always caused by a modern Western diet—is among the country’s leading killers.” This amounts to a “domination” more subtle than the Opium Wars or the overthrow of Central American governments—but not by much.

When something this big has gone wrong for this long, it becomes hard to imagine alternatives, or at least to imagine how those alternatives might possibly overcome the power of the ruling system. In the United States, for instance, there are 15 or 20 states whose senators largely represent corn; that’s why the Farm Bill, each time it’s renewed, is a gift to the industrial combines that control those states.

Bittman does discuss some interesting initiatives that are taking hold in different parts of the world and beginning to have a larger impact. Countries from Uruguay and France to South Korea and Taiwan have passed laws limiting junk-food advertising to kids, and they seem to work. Quebec, which banned such ads 40 years ago, has fewer overweight children than other parts of North America. In 2012, Chile—where half of 6-year-olds were overweight or obese—passed the world’s strongest food labeling and advertising laws. Any processed food high in calories, sodium, sugar, or saturated fat carries a “stop-sign-shaped ‘black label’” and can’t be advertised to kids under 14 or sold in schools; “almost instantly Chilean children went from seeing 8,500 junk food advertisements a year to seeing next to none.”

Mexico has also fought back as best it can; a tax on soda has driven consumption down 12 percent. Bittman cites more notable successes on the local level. Belo Horizonte, Brazil’s third largest metropolitan area, has bankrolled “People’s Restaurants” that sell high-quality lunches at affordable prices and cooked-from-scratch school meals emphasizing more vegetables and fewer processed foods; the government also subsidized farmers’ markets that sell staples at reduced prices and funded urban gardening programs. As a result, hunger in the city has been “nearly eliminated…while fruit and vegetable consumption and farmer income have risen.”

Even in the United States—the belly of the beast, as it were—Bittman finds some interesting developments. He describes the Good Food Purchasing Program, which began in Los Angeles in 2012 and sets standards for nutrition, animal welfare, environmental sustainability, and treatment of the labor force. When LA schools signed on, their main distributor started reaching out to wheat farms that could meet the new standards, which led to 65 new full-time, living-wage jobs. Cities from Boston to Oakland have signed on to the GFPP, and New York is about to join.

But more dramatic change will only come with initiatives like the Green New Deal, which “with carbon neutrality as a starting goal…would necessarily support…sustainable agriculture.” In fact, by the end of the book, Bittman uses the food crisis much as Naomi Klein did the climate crisis in her landmark This Changes Everything: as a lever for thoroughgoing change. “Instituting fairness in race and gender means in part undoing land theft, racial and gender-based violence, and centuries of wealth accumulation by most European and European American males, wealth accumulation that is still being compounded. This means land reform, this means affordable nutritious food regardless of the ability to pay…. This means wholesale change.” Indeed it does. “What’s for dinner?” has always been among the most basic of human questions. Now, asked honestly, it’s among the most unsettling and the most explosive.