‘Little Guantánamo’ Gets Bigger

Two secretive prison units that used to almost exclusively house people said to be connected to terrorism have expanded by nearly 80 percent in 15 years, and a new unit is on the way. Formerly incarcerated people say they have been used to punish dissent.

This story was produced in partnership with The Appeal with assistance from students at Syracuse University and the Data Liberation Project.

Months after being incarcerated for his role in one of the biggest American whistleblower cases in recent history, Daniel Hale suddenly went silent. Hale’s family and friends, who had been in regular contact with him after his 2021 trial, didn’t hear from him for several days. The judge in his trial had recommended that he go through a mental health treatment program in North Carolina, and be placed somewhere near his support network in Virginia, according to sentencing documents from his case. His friends and attorneys were baffled at his disappearance until another incarcerated person found a way to tell them he’d been transferred.

Then Hale’s friend, Noor, received a call from a federal prison in Marion, Illinois.

“The first thing he says to me,” she recalled, “is, ‘Don’t say anything, don’t say anything. Just listen.’”

Hale told Noor, who asked to be identified by her first name only, that he had been transferred to a Communication Management Unit (CMU) in Marion. He gave her the basics: At the CMU, their calls would be live-recorded and all his communications would be closely monitored; she couldn’t put him on speaker phone because the call would be cut; he’d be able to speak to her that day for only 15 minutes, and he needed all their friends’ phone numbers so that he could try to get them approved as contacts; he wasn’t allowed to give her messages for other people.

Noor had spoken to Hale a number of times after he was sentenced to almost four years in prison for leaking classified documents about the US drone program and its civilian casualties. But most of those calls had taken place while Hale was in county jail, awaiting a prison placement. Now that he was in the federal prison system, it was clear that everything would be different.

After the call, Noor started researching CMUs. She quickly learned that the units, sometimes called “Little Guantánamo” or “Guantánamo North,” were originally built to house people the federal government alleged had connections to international terrorism. The units, located as separate sections within two federal prisons in Marion, Illinois, and Terre Haute, Indiana, consist of single cells where people are held in isolation and subjected to intense surveillance and monitoring. People in CMUs have much less access to the outside world because of their status. They have extra limits on visits, phone calls, e-mails, and even postage mail. They can communicate only with approved contacts, and all communication is meant to be monitored.

Noor, who has been friends with Hale for more than a decade, said she didn’t know why someone whose crime involved no violence would be placed there.

“I don’t know the extent to which they were monitoring Daniel,” Noor said. “But maybe, they were like, Let’s teach him a lesson, and make sure that he isn’t able to use his voice again.’”

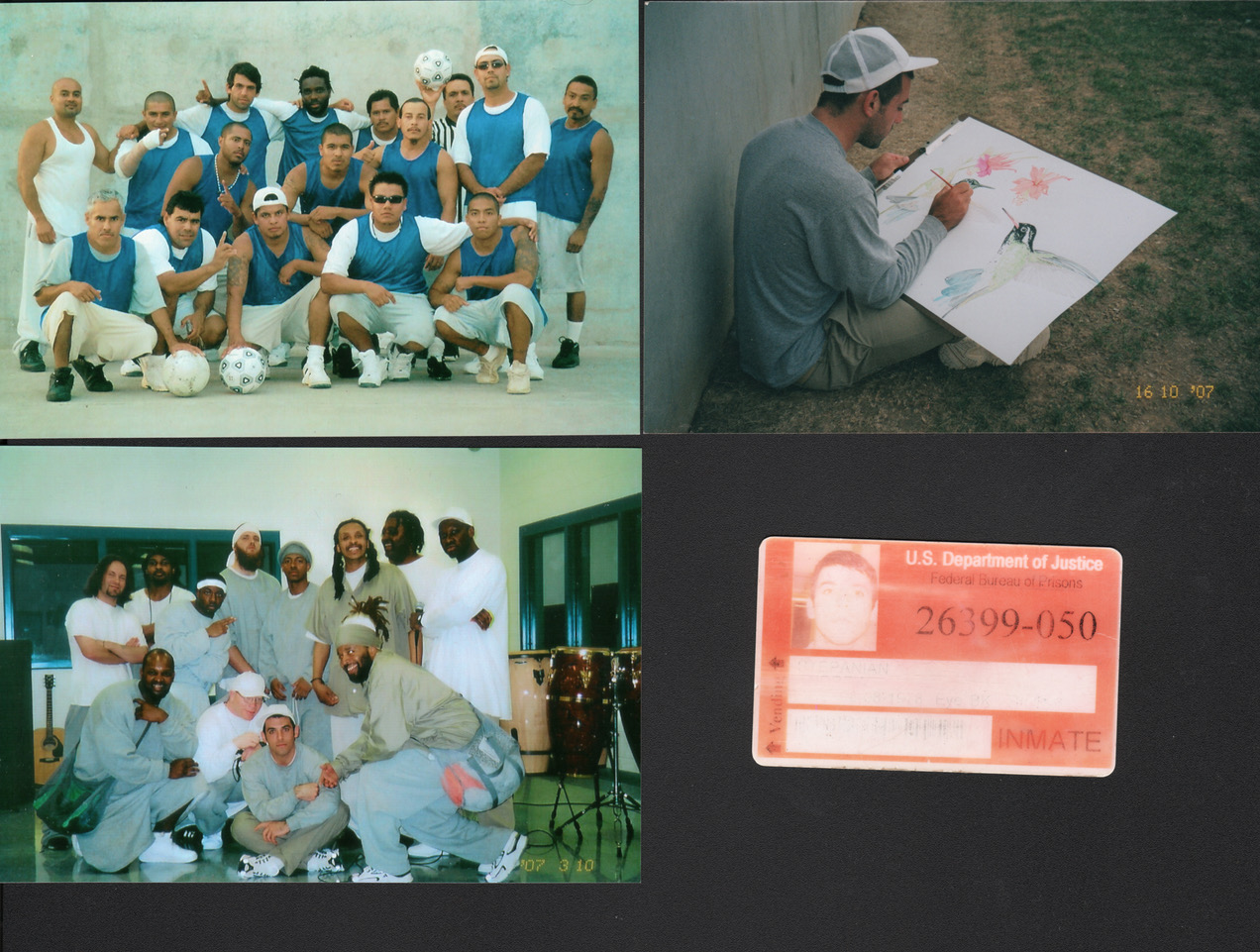

Hale’s case stands out among the hundreds of others who have been incarcerated in CMUs. The federal government quietly opened the two CMUs in 2006 and 2008 under a cloud of secrecy. There was no public hearing beforehand, and no apparent guidelines on the criteria authorities would use for placement in the units. When the CMUs opened, 70 percent of those incarcerated in them were Muslim men, who made up just six percent of the overall federal prison population at the time. This statistic was so startling that it became a key part of at least two separate lawsuits filed against the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) in 2009 and 2010 regarding CMU conditions and due process. Both cases were eventually dismissed because plaintiffs settled out of court or were released from the units, rendering their cases moot.

In addition to the critiques of CMUs as an Islamophobic manifestation of the US “War on Terror,” advocates have raised concerns that the units are often used to punish those who have expressed a strong opposition to American foreign policy—as Hale did so publicly.

An investigation of BOP data by The Nation and The Appeal now suggests that the federal government is expanding its use of CMUs, including with plans to build a new unit at a facility in Maryland. According to the most recent data, obtained by public records request, the number of people incarcerated in CMUs between 2007 and 2022 has increased 140 percent. Although the proportion of Muslims incarcerated in the units has decreased over time, that is largely due to the growth in the overall population. As of 2022, Muslims still made up 35 percent of the total CMU population. As of 2023, Muslims still made up 35% of the total CMU population.

Noor, who works as an organizer in Washington, DC, said she is worried that CMUs will increasingly be used to incarcerate whistleblowers like Hale, who have been prosecuted for exposing violent US policies.

Hale served in the Air Force and was stationed in Afghanistan from 2009 to 2013. It was there that he would experience what he called in a letter to the judge in his case “the most harrowing day of my life.” In 2012, a drone strike that he and his superiors deployed hit not only a man they were tracking, but also his wife and their two daughters, only 3 and 5 years old, resulting in the death of their eldest.

Two years after this incident, Hale leaked classified documents about the US drone program to a reporter. The resulting investigation, published by The Intercept, revealed the shocking number of casualties caused by drone warfare, and the flawed methods the government used to identify targets. Hale said his role in the strike on this family and his participation in the drone program pushed him to release the documents.

“The determined fighter pilot has the luxury of not having to witness the gruesome aftermath,” Hale wrote in the letter, “but what possibly could I have done to cope with the undeniable cruelties that I perpetuated?”

In July 2021, more than two years after his arrest, a federal judge sentenced Hale to 45 months in prison for violating the Espionage Act. He was released earlier this summer.

Hale did not respond to e-mails regarding this investigation.

In January, the BOP inked a $2.8 million contract with Virginia-based construction company PROCON International to convert a medium-security prison in Cumberland, Maryland, into a CMU. PROCON CEO Aziz Elham confirmed the conversion project in a text to The Nation and The Appeal, though neither he nor a BOP spokesperson would give further details. It remains unclear how many CMU cells the unit will contain, or if this is meant to be an additional unit or a replacement for existing units in the two other BOP facilities. In 2019, a federal prison in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, was scheduled for a mission change to become a CMU. According to the BOP, the change was never implemented.

An expansion of the CMU program may have always been the plan. According to a 2020 OIG audit of the BOP’s abilities to monitor incarcerated people, the agency had intended to establish up to six CMUs in order to better monitor “terrorist inmates.” The report, which, among many other aspects of monitoring, criticized the BOP’s list of who is or is not considered a “terrorist,” said that CMU equipment is “insufficient for BOP staff to perform adequate monitoring of certain terrorist inmate conversations.” The audit consisted of interviews with BOP staff and was conducted to “prevent further radicalization within inmates.”

In response to early scrutiny—including from members of Congress—over the high population of Muslims in CMUs, the BOP opened up public comment periods in 2010 and again in 2014. In 2015, the agency finally defined its policies for CMU placement, stating that connections to international or domestic terrorism were key justifications.

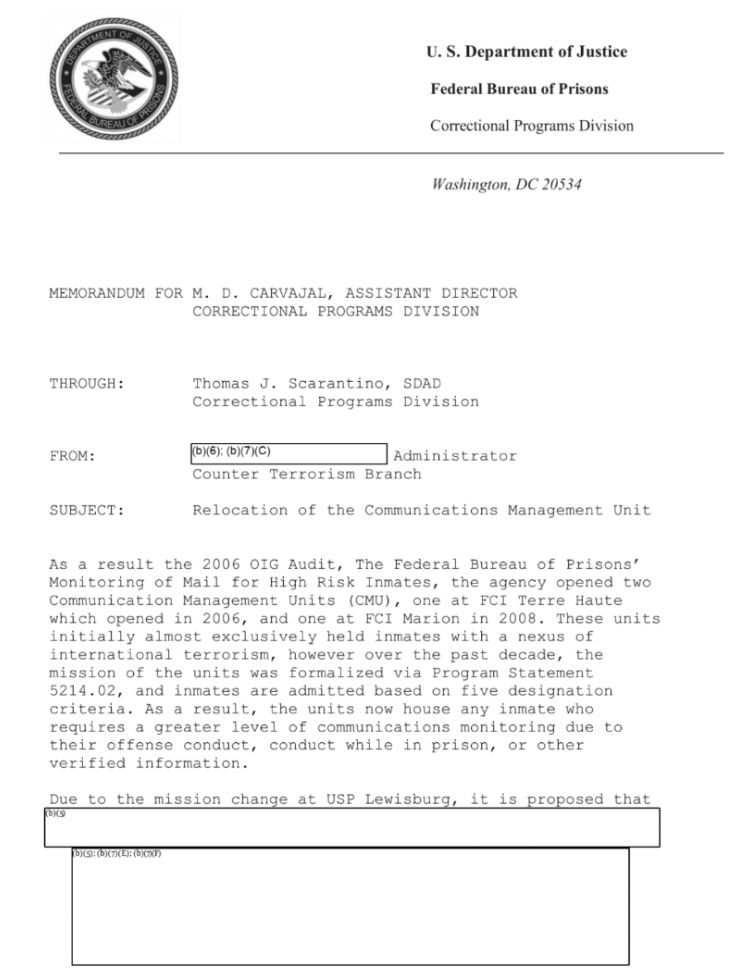

But internal BOP documents obtained by The Nation and The Appeal via public records request show that, despite recent criticism that the BOP is not even effectively monitoring those it has already incarcerated in CMUs, the agency has widened its criteria for CMU placement over time. CMUs are going from housing “almost exclusively” people judged by courts to have a connection to international terrorism to housing “any inmate who requires a greater level of communications monitoring.” The change in purpose of these units has resulted in some bloating, which has seen some people incarcerated in the units, like Hale, who the government admits have no ties to terrorism or even violence.

The BOP has not published comprehensive data about who has been incarcerated in CMUs over time. To get a better picture of the CMU population and how it’s changed, The Nation and The Appeal created a database with the convictions, nationalities, and certain case details for those previously or currently incarcerated in one or both of the units. An analysis of this database of almost 200 people, which reporters continue to build, shows certain trends: about one-third of the individuals in the database have no alleged affiliation with a terrorism group. This is in line with the 2020 OIG report, which criticizes the BOP for being unable to correctly identify those with a “known nexus to domestic or international terrorism.”

One-third of individuals in our database were arrested within the four years after 9/11. (Because the database was compiled partially with the help of advocates who work with those targeted by War on Terror policies, the data may be skewed toward Muslims and those who have been accused of having connections to foreign terrorist groups, whether or not those accusations were true.) The database also sheds light on law enforcement’s controversial use of informants and sting operations, as two out of every five CMU detainees in this database were arrested after being targeted by these sorts of tactics. These strategies have been criticized by Human Rights Watch and others for preying on the vulnerable, including youth, individuals with mental health issues, and undocumented people, and for encouraging their targets to commit acts that would be categorized as crimes. Sting operations and the use of FBI informants have increased after 9/11 and have resulted in many people being labeled “terrorists” who did not actually engage in any violent acts.

The label of “terrorism” has accumulated racial meanings over time, and has been used to justify state violence, writes race and terrorism scholar and Carleton University professor Atiya Husain. The US government and federal courts have expanded this definition in the post-9/11 era to target charities and speech, and as a tool to wield state power against those that come into the government’s disfavor. Mentions of “terrorism” in this database or in our investigation refer only to the US government or federal courts’ interpretation of terrorism.

A 2015 program statement says CMU designation is “non-punitive” and that referrals to a CMU can come from a counterterrorism unit, as part of a person’s sentencing computation, or from other law enforcement agencies. Beyond mentions of terrorism, the document states that someone can be designated to a CMU if there is “a substantial likelihood” that they will engage in illegal activity through communication, or that they will contact their victims. It also contains more open-ended criteria for designation based on “any other substantiated/credible evidence of a potential threat to the safe, secure, and orderly operation of prison facilities, or protection of the public, as a result of the inmate’s communication with persons in the community.”

Despite pending FOIA requests, the BOP has yet to release documents with additional information on people incarcerated in CMUs, including their underlying convictions and official justifications for placement in the units. In snapshot data obtained from the BOP last year, the highest share of people incarcerated in both CMUs each year had been convicted on charges categorized as “Fraud/Bribery/Extortion” or “Miscellaneous.” The only outlier year was 2007, when 11 out of the 44 people detained in the Terre Haute CMU had been convicted on “Weapons/Explosives” charges. “National Security” offenses are consistently at the bottom of the list for frequency each year.

A BOP spokesperson denied a request for an interview on the agency’s use of CMUs, stating that the office does not “interpret or research the data received through FOIA requests.”

One of the frustrating aspects of CMUs is that it’s difficult to predict who could end up in one, said Kathy Manley, an attorney who has been working with clients held in the units since they opened. She also said she’s not surprised by the expansion of CMUs beyond their initial use primarily to punish Muslim detainees.

“One of the things that always happens is that they’ll target a particularly hated group of people for new repressive projects,” said Manley. “Muslims convicted of terrorism or sex offenders—nobody cares about them, so we can take away some of their rights and say that it’s for national security purposes.”

Once established, she added, “we can keep expanding those norms through the rest of society.”

Manley has worked with clients in prison, some within CMUs, for more than 15 years. She said clients complain about arbitrarily being thrown into solitary confinement with no disciplinary charges filed, being moved between units at Marion and Terre Haute or transferred to the supermax prison for no clear reason, or being threatened with a transfer to a CMU if they want to challenge a disciplinary charge. One of Manley’s clients sued the BOP after he got sick following a stint in “the hotbox,” a particularly hot area of the Terre Haute CMU, which does not have air-conditioning. Another client swallowed a razor blade out of frustration at not being able to transfer out, she said.

Earlier this year, Manley and another Coalition for Civil Freedoms attorney had been denied legal calls with CMU clients. BOP officials told her they couldn’t connect them unless they had an imminent court deadline, and that the attorneys could visit instead.

The lack of communication from within CMUs also means the outside world has less information about the conditions and treatment of those inside.

Rachel Meeropol, former attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights, the civil rights organization that filed the 2010 lawsuit challenging CMUs, said the program’s nebulous placement criteria makes it ripe for abuse. She and other civil rights advocates have expressed concern that dissent is increasingly being categorized as “terrorism” for the BOP, and the CMUs are an example of this bloating.

“These units exist out there in a way that is very open to abuse in the future, and can be used against any politically unpopular group that comes into particular disfavor,” she said. “The way we saw them used against Muslims…it can be used in this way as a political prison.”

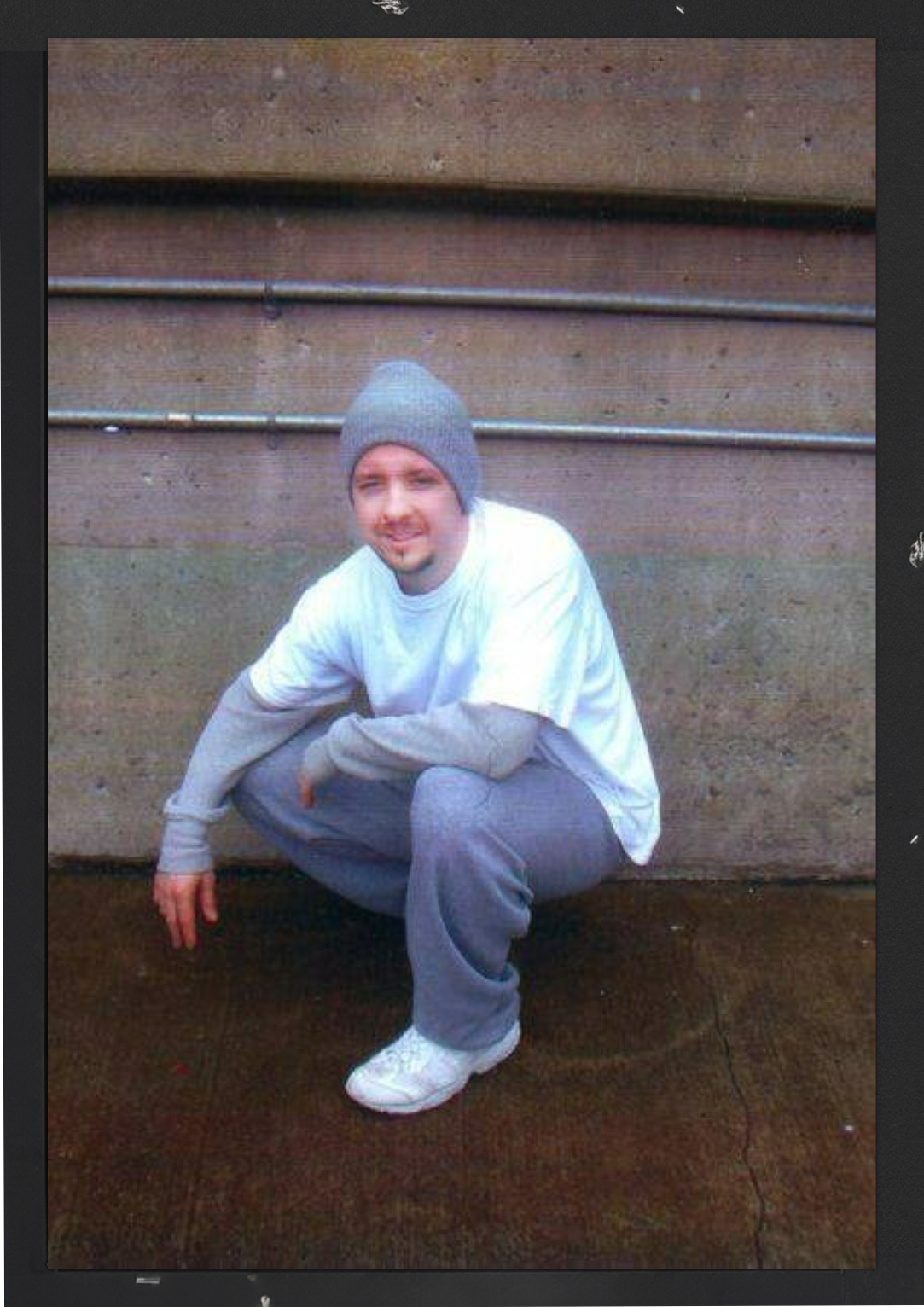

Environmental activist Daniel McGowan first heard about CMUs in 2007, as he and his legal team attempted to fight a federal terrorism enhancement tacked onto his case. While he ultimately lost this battle, resulting in a seven-year sentence for conspiracy and arson, the terrorism enhancement did not immediately land him in a CMU.

While incarcerated at FCI Sandstone, a federal prison in Minnesota, McGowan worked on a Masters degree in sociology and regularly wrote blogs and papers criticizing the US prison system. He knew the BOP was watching him closely, both for his writing and the stream of mail and visitors he received from the outside.

One day in 2008, without any notice, McGowan was told to pack up. The guards didn’t tell him where he was going until he was on the bus—“Marion,” they said. “Terrorist unit.”

The BOP cited McGowan’s writing as proof of his continued support for “radical environmental terrorist groups.” CMU transfers tend to be “a fly-by-night affair,” said McGowan, which allows the BOP to ship people off to these restrictive facilities with very little recourse. He spent much of the next four years in CMUs at both Marion and Terre Haute. In 2013, after McGowan’s release from prison to a halfway house, he wrote about his experiences with CMUs in a piece for HuffPost. McGowan says he was arrested at his halfway house and briefly jailed after publishing it.

The use of CMUs to punish critics of the United States has always been a cornerstone of the program, activists and formerly incarcerated people say. Many Muslims have landed in CMUs after speaking up against War on Terror policies, or indicating belief in certain Islamic principles.

Relying on broad policies for Muslims specifically was the original basis of the program since its inception, said University of Colorado law professor Wadie Said. The BOP established the units in response to criticism for allowing three men convicted of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing to send letters in Arabic, to outside contacts. These letters, some of which were sent to “members of a Spanish terror cell,” according to a 2006 report from the Office of the Inspector General about the incident, were perceived to be a security threat. Because of this incident, the report recommended that BOP consider applying special administrative measures, including enhanced surveillance, for anyone convicted of terrorism-related crimes, among other surveillance methods.

To Said, author of a 2015 book on terrorism prosecutions, the presentation of CMUs as a necessary response to “dangerous terrorists” follows a trend of sweeping, overbroad policy responses from the post-9/11 era.

“The thing about the terrorist angle is that it’s always an opening to put in place a holistic policy,” said Said. “Some guy tried to blow up a plane with his shoes, now we have to take off our shoes. Not individual, not more focused. Everyone is now affected.”

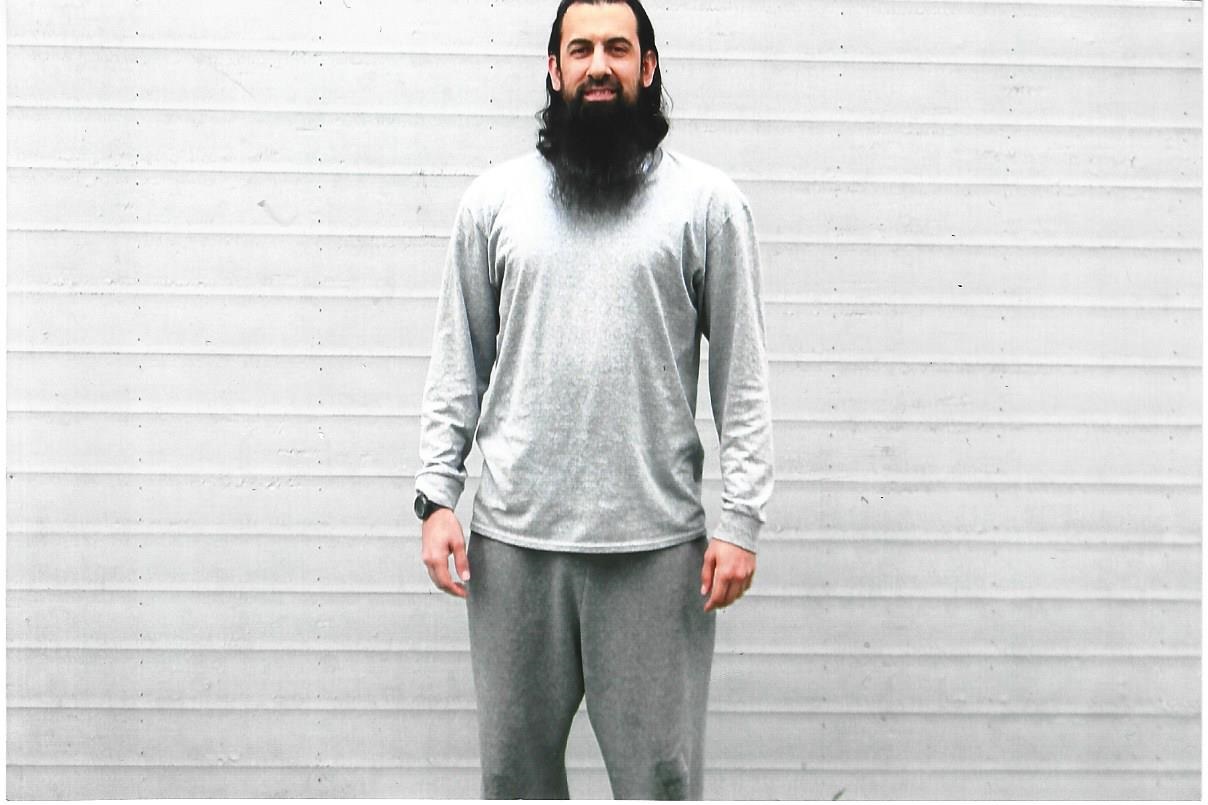

Stepanian was notified many days after his transfer that he had been sent to the CMU because of his affiliation with “domestic terrorist organizations.” He believes it was at least partly retaliation for raising grievances about negligence surrounding his friend’s death.(Andrew Stepanian)

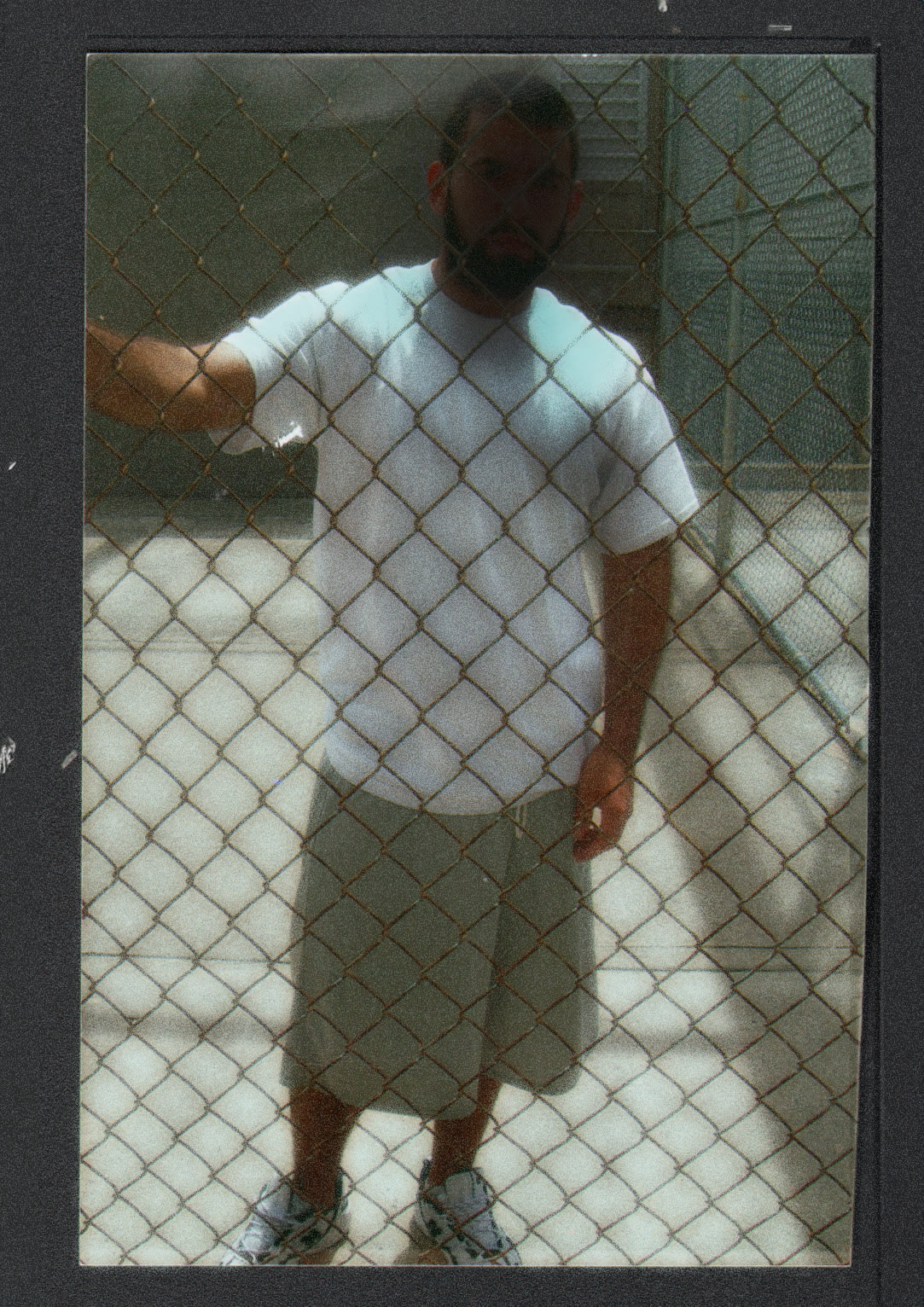

For Muslim men incarcerated in the CMUs, the risk of being punished for being “too radical,” with little explanation of what that actually means, is ubiquitous. This was the consistent throughline between Asif Salim’s case, incarceration and CMU detention.

When Asif Salim was incarcerated in a New Hampshire federal prison just miles from Mount Washington, he was put in solitary confinement for three months. Salim, who is Muslim, said prison officials told him he was being punished for having a book called “The End of the World: Signs of the Hour, Major and Minor.” He hadn’t faced any disciplinary actions before or after that, and at the time, he had no idea how long he’d be held there. Salim said BOP staff were concerned about his educational influence among the prison’s Muslim community, which was also a reason given for his later transfer to a CMU.

Salim was convicted in 2018 of “concealment of funds used to support terrorism.” The charges stemmed from a $2,000 check he’d sent to a friend in 2009, which he said was for his fishing supply business. Salim wasn’t arrested until 2015, and the government alleged the check from 2009 was part of a conspiracy to eventually send $22,000 to Anwar Al-Awlaki, the Yemeni-American preacher who was placed on the U.S. terror watch list in 2010, and subsequently killed in an American drone strike the next year. A fact that was not contested by either side was that Salim had had no contact with Al-Awlaki nor anyone in a terrorist organization, and he has denied participating in any kind of criminal activity. The case relied heavily on emails between Salim and three friends and, in an attempt to dismiss the case, his lawyers clarified that out of 18 emails where Salim was included, he was blind carbon-copied (BCC’d) on most of them with no comment from him. The government dropped their initial indictment and Salim, facing pressure at the time, eventually agreed to a plea deal on concealing funds with a sentence cap of eight years. He was sentenced to six years.

In solitary, Salim said, counterterrorism unit officers visited him and asked what they should be doing with “people like him.” He told them they were engendering further contentiousness between incarcerated people and the BOP, rather than trying to heal the situation. When they asked him what he thought about American foreign policy, he said he knew not to reveal any specific opinions.

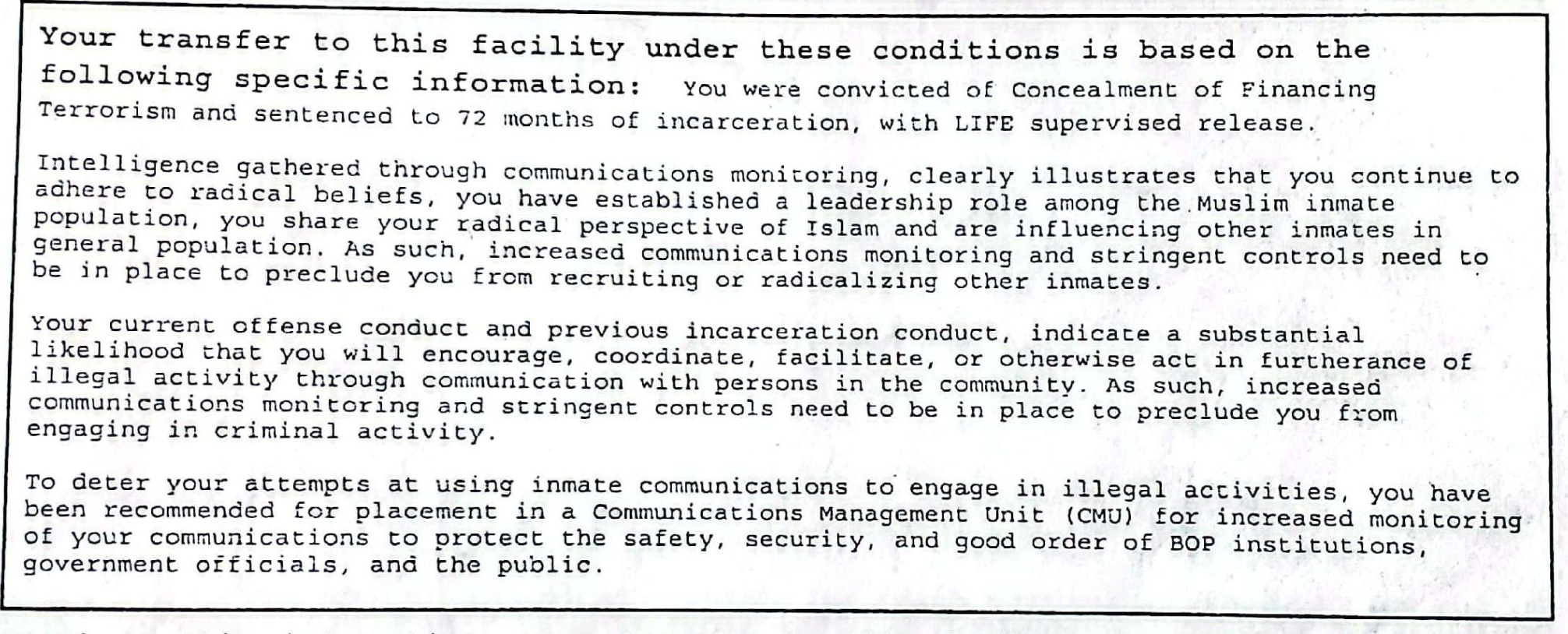

About a month later, Salim was transferred to the CMU in Marion. His “Notice to Inmate of Transfer” document stated that he was being moved because BOP officials were worried he’d share his “radical perspective of Islam” with other incarcerated people.

Salim said the process of being transferred to a CMU was particularly frustrating because he wasn’t told until after he got there why he was being sent, and he was not given any opportunity to dispute any of the claims made against him within it before his transfer. He called the document “an arbitrary, unilateral declaration about me that could not be challenged.”

“The document mentions my alleged ‘illegal activities’ more than once,” he said. “If this was the case, why wasn’t I given a disciplinary shot [internally, by the BOP] or even a new charge [from the FBI]?”

The notice mentions an appeals process, but formerly incarcerated people and advocates have noted that the chances of getting out via appeal are very low, according to court documents from the 2010 lawsuit against the BOP regarding the units. Lawyers in that case said the lack of process for giving detainees prior notice regarding their transfer nor a meaningful appeals process “establishes a situation ripe for abuse through retaliatory and discriminatory designation.”

Kifah Jayyousi, who was incarcerated in a CMU for five years, appealed his placement and was denied, in part because of a sermon he made calling the units “concentrated Muslim units,” and encouraging fellow CMU detainees not to become informants. During his time at the CMU, he was not allowed direct contact with his children. Every interaction took place through the phone and plexiglass.

Communication from CMUs to the outside world is extremely limited. According to the 2020 OIG report, each detainee is allowed up to eight hours of no-contact visiting time per month and two 15-minute live-monitored phone calls per week. During holiday months, they are supposed to get an extra 15-minute phone call per week. During visits, parties are separated by a wall of plexiglass. Phone calls can only take place with approved contacts. E-mails can also be limited to two per week, at the discretion of the warden. Those held in CMUs are also some of the very few people living in BOP special housing units who have limits to postage mail: They are allowed to send six pieces of paper, double-sided, to one contact once per calendar week.

Visits could be cut short at the discretion of wardens or security monitors, and were available depending on the situation in the unit on a given day, according to former CMU detainees.

In comparison, a person incarcerated in a general population unit like FCI Pekin is technically allowed up to 40 hours of visitation per month. They also get 300 phone minutes every month—more than twice as much as CMU detainees receive most months. People in general population units also typically get access to classes and activities, both of which are limited to those in CMUs.

Jayyousi’s daughter, Sara, now 28, said her father’s incarceration in a CMU had caused lasting damage to his mental health and their relationship, even after his release in 2017.

“Trauma just doesn’t disappear the way that you’d think it would. Not even with time,” she said. “When he did come out, it wasn’t like some kind of celebration or anything like that. It was him dealing with his PTSD from being in the CMUs.”

The BOP argued in 2015 that its policies limiting communications between incarcerated people and the outside world passes the “Turner test,” a set of factors used to determine whether a prison regulation violates an incarcerated person’s rights. But Terry Kupers, a psychiatry professor at the Wright Institute who studies prison conditions, said that CMUs, like the more widely discussed solitary confinement cells, have a uniquely detrimental effect.

“A lack of communication with people outside of CMUs coupled with secrecy on the part of the BOP can be damaging to an inmate’s mental state,” said Kupers, who is also a Human Rights Watch consultant.

Several studies have shown that maintaining relationships on the outside is critical to one’s ability to transition back to normal life after incarceration. The conditions of CMUs actively undercut those goals.

“We’re still stuck on two opposite sides of plexiglass, and that’s just how it’s going to be,” Jayyousi said of her father.

When Asif Salim wanted to speak to his mother in Pashto from the CMU, he had to register the phone call and language a week ahead of time. The conversation would be allowed only if a translator was available. If they drifted into a different language, the call would be immediately cut. On at least one occasion, Salim said, BOP staff deleted e-mails containing the Arabic word inshallah, an extremely common phrase amongst all Arabic-speaking and Muslim people, meaning “God willing.”

In May, Salim convened with civil rights advocates at Atlanta’s Masjid Maryam, an Islamic center where he is a member. As part of a series of panels organized by the Coalition of Civil Freedoms, speakers encouraged the community to support Muslim political prisoners and remain vigilant against law enforcement incursions. They drew a line between post-9/11 surveillance and more recent efforts to target students protesting what many scholars are calling a genocide of Palestinians in Gaza by Israel, often by concocting supposed ties to Hamas, which the United States deems a “foreign terrorist organization.” The group explained that these tactics have landed politically active Muslims in prison—and from there, into CMUs—and that knowing how to avoid them is crucial to advocacy work.

Earlier this year, The Intercept reported that the Department of Homeland Security was working on college campuses to fight what the agency referred to as “foreign malign influence.” Investigative reporter Ken Klippenstein reported that Congress has pressured the FBI to use informants in their monitoring of anti-war protests on campuses, mirroring tactics used after 9/11 to target and often entrap protesters, and particularly Muslim students.

The similarities between today’s environment and the post-9/11 era have been clear to Jayyousi, who said she’s been mistrustful of the federal government since her father’s arrest.

“You can’t talk about where you’re from. You can’t talk about what you support or what your religion is, or your background, your cultures, because it’s too dangerous,” she said.

At the Atlanta events, speakers encouraged parents to talk to their kids about how to safely protest war and advocate for Palestine without falling prey to informants or FBI officials looking to connect young people to US-designated foreign terrorist groups. The masjid was filled with people after Friday prayers who listened intently and laughed at the panelists’ jokes about how Muslims are often too friendly to police and FBI officers: “Don’t invite them in,” one panelist joked. “Don’t offer them chai or laddoos.”

Salim has firsthand experience with law enforcement’s history of targeting students.

While attending Ohio State University from 1998 to 2005, Salim became aware that the FBI was surveilling him after he participated in campus events around the time of then–Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Al-Aqsa mosque compound in East Jerusalem, which drew global backlash. As part of the school’s Muslim Students Association, Salim said he and other MSA members had set up tables on campus to talk to people about Islam, which, because of the timing, other students interpreted as part of the political protests. After the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, Salim said FBI agents began to visit his home.

Salim now has four kids, age 10 to 16, and he said he tries to frame what happened to him as a part of a much longer historical thread. On the Atlanta panels, he compared the relationship between US authorities and pro-Palestinian protestors to the one between Pharaoh and Moses—or Fir’aun and Musa in the Qur’an.

“Fir’aun said about Musa, ‘He is trying to cause mischief and corruption on Earth,’ when indeed, Fir’aun himself was actually Mr. Corruption,” said Salim. “That was then, and nothing has changed. They still paint us as the corrupters and mischief-makers, when in fact, they are the corrupters and mischief-makers.”

Database methodology

This database was built over the course of more than two years, and through the contributions of many reporters, formerly incarcerated individuals and civil rights groups.

The BOP’s inmate locator does not specify who has been placed in a CMU versus a general population unit. As far as we know, this information is not made public in a consistent manner elsewhere. The reporters on this project began by soliciting names and stories from those who have been doing this work for many years, specifically the Coalition for Civil Freedoms (CCF) and Kathy Manley, Daniel McGowan, who was formerly incarcerated in a CMU, and a 2011 NPR database about CMUs built by Margot Williams and Alyson Hurt. We collected more names by creating a survey for those who had been incarcerated in a CMU, or their family and friends, and distributing through the CCF weekly listserv. We also collected names and stories from news reports over the years.

In order to standardize the information we received from many different sources, four Syracuse University journalism students, led by Haley Moreland, used PACER to look up each individual person and their case to find details like their convictions, their sentence, and whether or not they had a federal terrorism enhancement put on their case. If their information was not easily available via PACER, the reporters used other websites, including FindLaw, court documents from civil rights groups, like the ACLU and the Center For Constitutional Rights (CCR) and news reports to fill in information. The database was then fact-checked by Saliha Bayrak, and edits were made by reporters. The database was further standardized through the general editing process, and reporters and editors decided to publish an anonymized version.

Details on some columns:

> Conviction summary: For the sake of consistency, we have attempted to summarize convictions by using broad legal terminology and removing the number of counts on each conviction. Although we have attempted to remove any convictions dropped on appeal and include relevant past convictions, these summaries may not be reflective of the most up-to-date information as this is an ongoing project.

> Arrest and release dates: The date of arrest should reflect an individual’s initial date of arrest, including if someone was arrested outside of the U.S. and later extradited, or if an individual has received multiple indictments. If an original arrest date is unavailable or unclear, we’ve marked it as N/A. We’ve generally tried to stick as close to the initial arrest date as possible. Arrests that did not lead to jail time/convictions were not included. This database is also missing the date each individual was transferred to a CMU after their initial imprisonment, which is not publicly available data. Also, some release dates are approximate because the BOP does not update these regularly.

> Sentence: If an individual has multiple consecutive sentences, the format we used is “XX years plus XX years.” If the individual was already in prison for an unknown sentence, had a concurrent sentence added to their initial sentence, or if it is unclear whether the added sentence was to be served concurrently or consecutively, the format we used is “XX years (already serving an X prison term).”

> Nationality: We have tried to specify the nationality of each person and have indicated when they are a naturalized US citizen.

> Federal terrorism enhancement: Whether or not a person had an enhancement placed on their case can only be confirmed through access to sentencing transcripts or the judgment file, which is not publicly available for each individual on PACER. We’ve marked this column “Yes” only when we could confirm the application of a terrorism enhancement, and defaulted to “No” when we could not confirm with the information available to us.

> Stings/informants: We consider stings to be law enforcement stings, typically run by the FBI, and informants to be paid informants, rather than someone tipping law enforcement off about a potential crime. We include jailhouse informants, who often receive a reduction on their sentence if they work with law enforcement, as paid informants. We did not include foreign intelligence agencies as informants or stings.

This database is not complete nor comprehensive, and we are filling it in and correcting it all the time. If you or someone you know was or is currently incarcerated in a CMU, please fill out this form to clarify or update your information: https://tinyurl.com/CMU-share. The complete version of the database, including names and other details of those incarcerated, will be shared only with those who are working on this topic. If you are a researcher, journalist, or working for a civil rights group, and you’d like to use the complete database for your own work on CMUs or incarceration, please e-mail the lead reporter on this project: [email protected].

-

- Reporters: Nausheen Husain, Aly Panjwani, Haley Moreland

-

- Database: Haley Moreland, Olivia Boyer, Nada Merghani, Sorem Oppenheimer

- Data Visualization: Ethan Corey

-

- Fact-checking: Saliha Bayrak

-

- Editors: Ludwig Hurtado (The Nation), Ethan Corey (The Appeal)

-

- Some data obtained with the help of the Data Liberation Project and Jeremy Singer-Vine.

More from The Nation

The Disturbing History of ICE’s “Death Cards” The Disturbing History of ICE’s “Death Cards”

The Vietnam-era practice is yet another example of ICE agents thrilling to the brutality they have been encouraged to cultivate.

The Red State–Blue State Healthcare Divide Is Dangerous for Everyone The Red State–Blue State Healthcare Divide Is Dangerous for Everyone

Whether or not you have access to independent, scientifically sound public health guidance may depend on how your state voted for governor.

The American Universities Programming Israel’s Killer Drones The American Universities Programming Israel’s Killer Drones

Industry partnerships in higher education are pushing STEM graduates into the business of weapons manufacturing and genocide profiteering.

In the Trump Era, Celebrating Black History Month Feels Radical Again In the Trump Era, Celebrating Black History Month Feels Radical Again

After putting on their very best performances of solidarity every Black History Month, this year corporate marketers have seemed at a loss for words.

ICE’s Detention of Pregnant People Continues a Disgraceful American Tradition ICE’s Detention of Pregnant People Continues a Disgraceful American Tradition

We are seeing yet another example of state-sanctioned violence against the reproductive futures of those deemed outside the national body.

The Price of Being Black and Proud in European Soccer The Price of Being Black and Proud in European Soccer

The Brazilian star Vinicius Jr. has repeatedly been a victim of racist abuse from soccer fans. Now, it seems such vitriol can even come from players without much consequence.