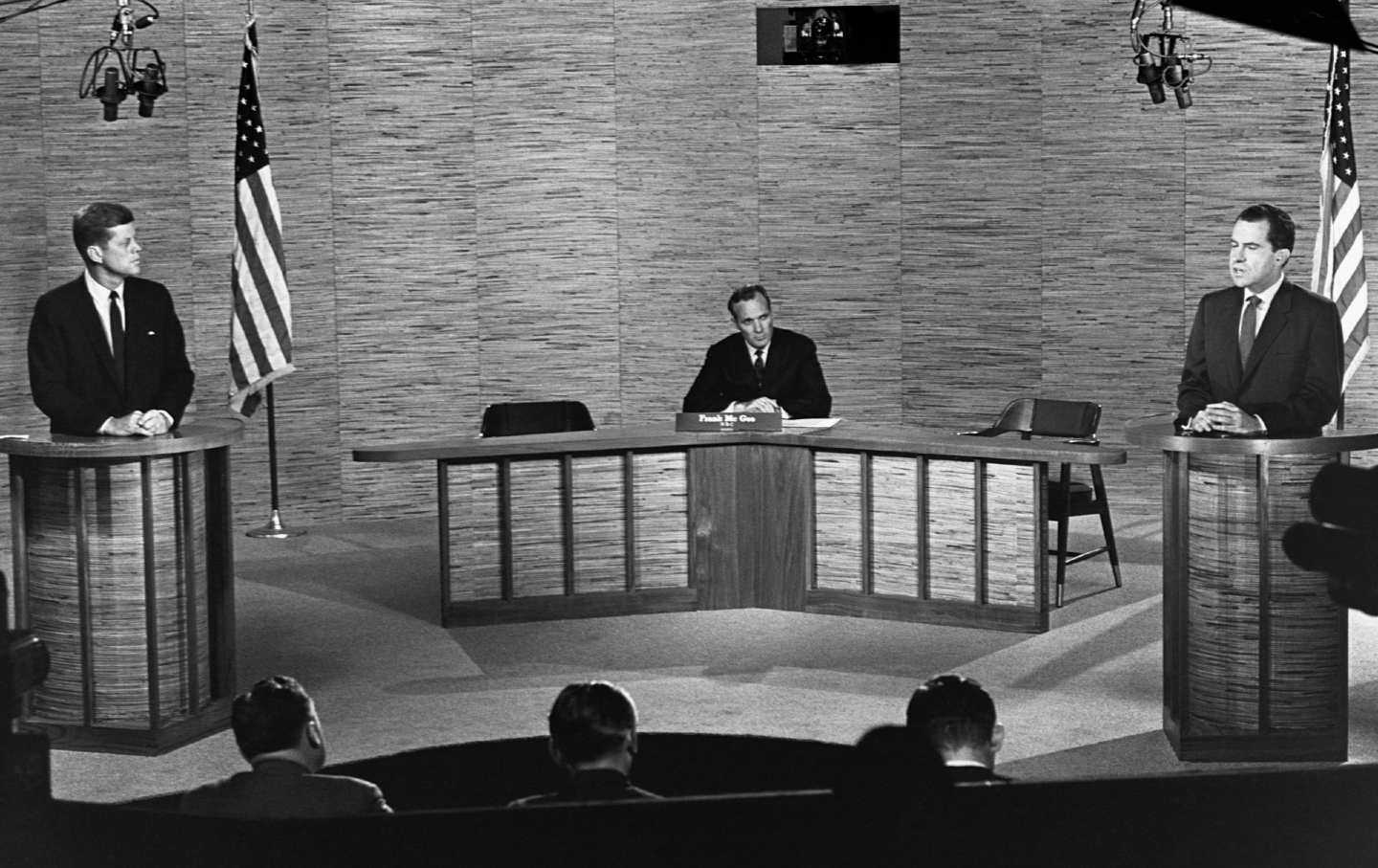

John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon stand at podiums during one of four televised debates in 1960.

(Corbis / Corbis via Getty Images)

From winner-take-all elections to the Electoral College to the legalized bribery that is campaign finance, the United States has an absolutely bonkers system for picking its leaders. One would be hard-pressed to design a process more conducive to hucksterism, corruption, gridlock, and the widespread distrust of government.

But perhaps the greatest absurdity is the televised presidential debate. The skills required to win a match of verbal jousting have little to do with those that make an effective chief executive. It’s dismal to think of the competent, comparatively moral American political leaders who’ve been denied a bid for high office because their acting chops weren’t up to snuff, and even more painful to recall the vapid, unprincipled performers we’ve gotten stuck with because theirs were.

As we head into yet another debate season, it’s hard to imagine a time when the practice of TV debates between presidential contenders was new. For that we have to turn all the way back to the historic showdowns between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Today, most of what gets remembered about those four televised debates is Nixon’s 5 o’clock shadow and Kennedy’s youthful glow. But there was a lot more to them than that, as the package of responses that appeared in the November 5, 1960, issue of The Nation reminds us.

To the Brown University historian W.G. McLoughlin, one of the experts The Nation asked for comment, the televised encounters had “more of the quality of an advertising gimmick than of a radical political departure…. The debates added no new elements to the issues under discussion, and the candidates quickly reworked their campaign speeches into the simple answers required for a ninety-second rebuttal.” Even when an important point came up, it soon “became obscured in a mass of qualification, backtracking, contradiction and ad hominem quibbling.”

Alan Harrington, a novelist, thought the debate could best be understood as a personnel interview for an important vacancy. There was something democratic about the spectacle of leaders called to account for their stances before millions of viewers:

For the first time since our country came into being, virtually everyone has had the chance to watch the candidates—if not in the flesh at least in close-ups larger-than-life—under merciless conditions in which the smallest fumble, mumble, hint of hesitation or drop of perspiration is instantly magnified and placed on the record beyond hope of denial.

It was useful, too, Harrington suggested, for voters to see the job-seekers “placed under conditions of stress,” to “observe how the applicants think on their feet.” Harrington was impressed by Kennedy’s strength and maturity, and decided he’d vote for the Democrat after previously thinking he’d sit the election out.

All in all, Harrington thought the debates would prove a useful addition to the quadrennial campaign ritual. But the writer did make a prediction that hasn’t quite held up: “One thing is likely—if TV debates of this kind become a matter of American political custom, all future Presidents of the United States, whatever their principles, will at any rate be quick and articulate men.”

The poet and critic Kenneth Rexroth offered a similar hope. Though he thought the debate pointless and unremarkable, Rexroth figured its introduction might have “one small demonstrable merit…. As time goes on, television may well purge American politics of gross ill manners.” Television revealed too much; it had showed Senator Joseph McCarthy to be an uncouth scoundrel. Rexroth wrote, “I don’t think there is any question but that it would be impossible today to run, much less elect, a gross buffoon, a ruffian, or even a boozy, good-natured rascal.”

The advent of presidential debates ended up seeming a bit anticlimactic to observers in 1960, but in a way that would ultimately prove deceiving. As the fiction writer Don W. Kleine noted in his contribution to the Nation forum, the two performers appeared wary of exercising the full possibilities of the medium: “It is as if the participants had tacitly agreed not to go too far, as if each knew how fearful the consequences of spontaneity might be.” Even though both Kennedy and Nixon were already well-known as masters of political image-making, the encounters had revealed them as all-too-human. The camera caught Nixon “surprised in attitudes of gloomy unease, as if he had blundered into the studio on the way to the washroom,” while Kennedy, whose health had become a minor issue during the campaign, was seen occasionally wincing in pain. “Certainly,” Kleine sighed with relief, “neither is that creature whose emergence an age of mass communications had taught one to expect—the abominable showman, the unprincipled entertainer-politician coolly ‘projecting’ a false image into the living rooms of the naive masses.”

It took 50 or 60 years, but here we are. The abominable showman has said he wouldn’t have made it to the White House in 2016 without the TV debates, and he’s probably right. Should they be scrapped? It would be hard to claim they add much information that is new or useful, and they clearly play into the worst horse-race-obsessed habits of those mainstream political journalists who seem to make a living out of missing the point. In any case, the practice has become so embedded in American politics that eradicating it would hardly be easier than getting rid of the Electoral College—and, well, good luck with that.