Elizabeth Warren electrified a December town hall meeting in Iowa when she answered a question about the Electoral College with a stirring call to action. “I want to get rid of it,” she declared. “My goal is to get elected and then to be the last American president to be elected by the Electoral College. I want [my] second term to be that I got elected by direct vote. I’m ready!”

Warren may be ready, and her critique throughout the current campaign—“Call me old-fashioned, but I think the person who gets the most votes should win”—is right. But for the most part, Democrats have been slow to recognize the immediate and long-term challenges they face when it comes to the Electoral College.

They’re good at griping about the 18th century construct that has cost their party the presidency twice since 2000, but they lack a sense of urgency when it comes to addressing this barrier not just to their own electoral prospects but also to democracy itself. That lack of urgency could give Donald Trump a second term that’s every bit as undeserved as his first.

“I believe whoever the [Democrats nominate] is going to win by 4 to 5 million popular votes. There’s no question in my mind that people who stayed home, who sat on the bench, they’re going to pour out,” said the filmmaker Michael Moore, a Michigan native who has been a blunt, sometimes unsettling truth teller on the state-based dynamics of presidential voting, in an interview on Democracy Now! in December. “The problem is…if the vote were today, I believe [Trump] would win the [states] that he would need.”

That’s a chilling prospect for Democrats, who have not gotten over the fact that their party’s 2016 nominee, Hillary Clinton, won the popular vote by nearly 2.9 million ballots and yet narrowly lost three states that have traditionally voted Democratic—Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—and with them the presidency.

Moore’s assessment is a sound one, but we should begin by recognizing that he may actually be underestimating the antidemocratic potential of the Electoral College. The New York Times’ Nate Cohn ran the numbers and determined “it is even possible that Mr. Trump could win while losing the national vote by as much as five percentage points.” This suggests the prospect that Trump could go into the election trailing his 2020 Democratic opponent by a wide margin in the polls, lose the actual vote by 6 million or even almost 8 million votes, and still serve a second term.

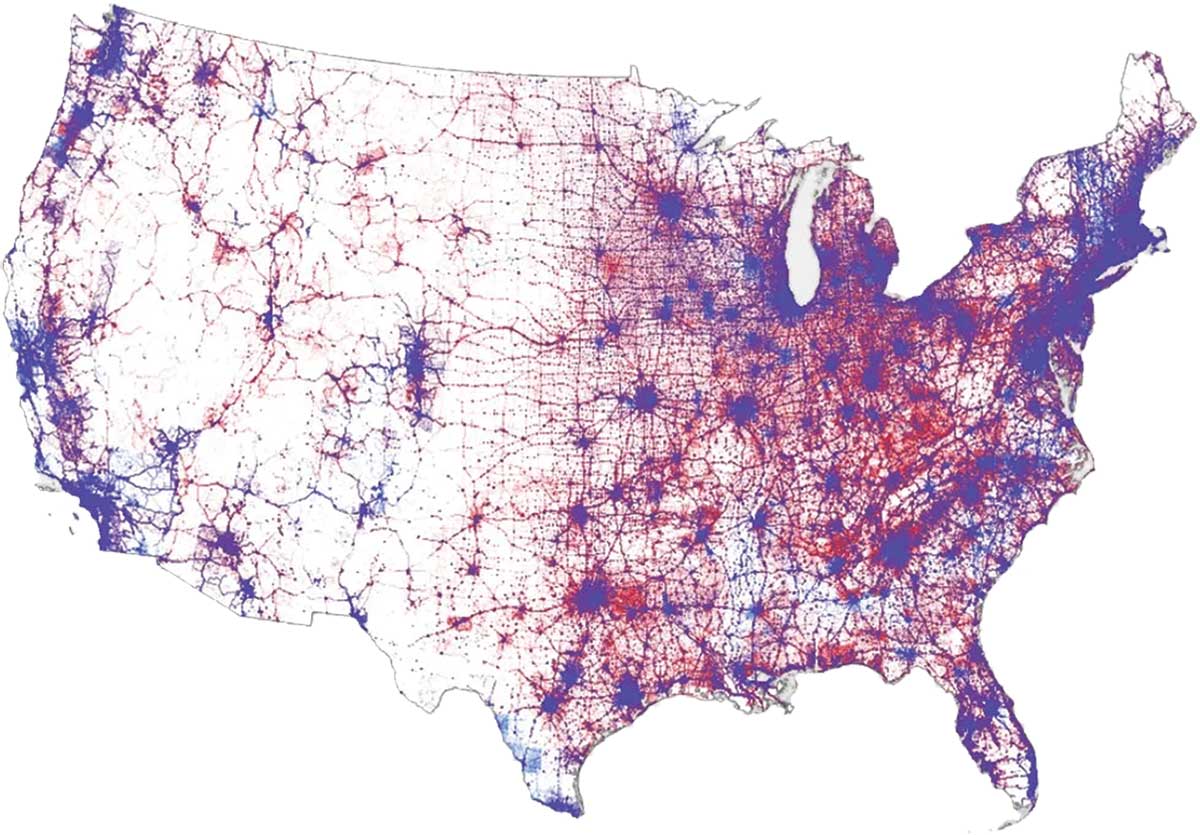

For perspective, consider this: The 2020 Democratic nominee could beat Trump by a wider popular-vote margin than that enjoyed by Barack Obama in 2012 or George W. Bush in 2004 and still lose. “That’s because the major Democratic opportunity—to mobilize nonwhite and young voters on the periphery of politics—would disproportionately help Democrats in diverse, often noncompetitive states,” explains Cohn. “The major Republican opportunity—to mobilize less educated white voters, particularly those who voted in 2016 but sat out 2018—would disproportionately help them in white, working-class areas overrepresented in the Northern battleground states.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Even if the Democrats manage to do better this year, The Cook Political Report’s David Wasserman warns of an “ultimate nightmare scenario” in which their presidential candidate wins the popular vote and “converts Michigan and Pennsylvania back to blue. But Trump wins re-election by two Electoral votes by barely hanging onto Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, Wisconsin, and Maine’s 2nd Congressional District—one of the whitest and least college-educated districts in the country.”

For Democrats, however, that would just be the start of the nightmare. Because it is biased toward small states that tend to favor Republicans and undervalues large coastal states where Democrats run well, the Electoral College is resistant to demographic shifts that should favor the Democrats. No matter how small a state’s population, it gets at least three electoral votes—two for its senators and one for its House member—out of a fixed total of 538. In 2016, Trump carried the least populous state, Wyoming, with 68 percent of the vote, while Clinton won the most populous state, California, with 62 percent. But because of the small-state bias, it took just 58,140 Trump voters to secure each of Wyoming’s three electoral votes, while it took 159,160 Clinton voters apiece to win California’s 55 electoral votes. Of the seven small-population states (plus the District of Columbia), Trump won five in 2016, for an advantage of six electoral votes.

That may not sound like much, but remember that in 2000, Bush had a similar small-state cushion of seven electoral votes (after a DC abstention) in a year when his Electoral College tally was 271 to 266.

And that’s not even the worst of it. Because of the winner-take-all system by which most electoral votes are allocated, tens of millions of votes cast for losing candidates are effectively discarded, and the highest level of disenfranchisement occurs in the battleground states where elections are decided. In 2016, Trump took Michigan by 10,704 votes, Wisconsin by 22,748, and Pennsylvania by 44,292, yet he got all of their electoral votes. More than 6.5 million Clinton votes were effectively discarded in those states. At the same time, millions of Trump votes were discarded in solidly Democratic states like Illinois and Massachusetts. “The Electoral College really does fail voters for both parties,” says Rob Richie, the president and CEO of the election reform group FairVote.

That’s a good argument for getting Republicans—at least in some states—on board for the popular election of the president. But the reality is that, where it matters most, the current system favors the Republican nominee and will continue to do so.

This is why Democrats should make the Electoral College a political issue in 2020—as Warren has done most aggressively, though a few others, such as Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders and former South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg, have also been outspoken. Most voters favor the Electoral College’s abolition, and the issue has potential as a tool for mobilizing the party’s base: 81 percent of Democrats favor electing presidents with a popular vote, according to a June 2019 NBC News/Wall Street Journal survey. But this is about more than merely organizing Democrats for 2020; it’s a matter of long-term survival. A 2019 University of Texas study of the “inversions” that occur when the winner of the popular vote loses in the Electoral College determined that “in the modern period…Republicans should be expected to win 65 percent of Presidential contests in which they narrowly lose the popular vote.”

For the sake of their own future, Democrats must become the party of Electoral College abolitionism. They must make it a part of their platform, their legislative agenda, and their messaging strategies. They must seek to build coalitions that include third-party supporters and honorable Republicans (32 percent of whom supported popular election of the president in the NBC News/Wall Street Journal survey).

Skeptics will, of course, rush in with the “news” that it’s hard to change a system set forth by the Constitution. That’s always been true. But it took constitutional amendments to extend the franchise to women, former slaves, and 18-year-olds; to bar poll taxes; to let residents of the District of Columbia vote in presidential elections; and to create a directly elected US Senate. Every one of those crusades required massive organizing, educating, sacrifice, and strategy.

There is a strategic approach for Electoral College abolitionists in the short term: supporting the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, which asks states to bind their electors to the winner of the national popular vote and not to their own results. Fifteen states and DC, with a combined 196 electoral votes, have adopted the compact, which can take effect only when states with a combined total of 270 electoral votes (the minimum needed to secure the presidency) sign on. With endorsements from the League of Women Voters, the NAACP, Common Cause, and other national advocacy groups, this is a serious effort that has made steady progress.

“Every year,” says National Popular Vote chair John Koza, “we add a state or two, and that’s what we plan to keep doing from now until it becomes law.” FairVote’s Richie sees the compact as complementing efforts to open congressional debate on abolishing the Electoral College; so too, he says, are the efforts by Harvard Law professor Lawrence Lessig to get the Supreme Court to clarify standards regarding so-called faithless electors, who decide not to support the candidate they are pledged to back.

While these projects are important, the most vital immediate activism could well involve the bully pulpit. Democrats need to get better at preaching the gospel of popular democracy in a way that makes the elimination of the Electoral College part of a vision for addressing money in politics, gerrymandering, and voter suppression. The party cannot drift back toward the unthinking approach that has seen it fail to push for fundamental reform when it had governing majorities.

Democrats should begin by shredding the myths about the Electoral College and recognizing it for the abomination it has been since slaveholding delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 worked overtime to restrict popular democracy. “Of the considerations that factored into the Framers’ calculus, race and slavery were perhaps the foremost,” Brennan Center for Justice fellow Wilfred Codrington III argues. “More than two centuries after it was designed to empower southern whites, the Electoral College continues to do just that.”

But it doesn’t stop in the South. In 2016 the Center for Economic and Policy Research noted in a study, “The states that are overrepresented in the Electoral College also happen to be less diverse than the country as a whole. Wyoming is 84 percent white, North Dakota is 86 percent white, and Rhode Island is 74 percent white, while in California only 38 percent of the population is white, in Florida 55 percent, and in Texas 43 percent.” As such, the study continued, “the Electoral College not only can produce results that conflict with a majority vote, but it is biased in a way that amplifies the votes of white people and reduces the voice of minorities.”

When debates about the Electoral College are placed in such stark terms, they frame the moral case for abolition. But to address the long-term crisis, Democrats must run against the Electoral College while seeking to master it in 2020.

Polling by The New York Times’ Upshot and Siena College in October 2019 found that Trump remained “highly competitive in the battleground states likeliest to decide his re-election.” Those closely divided states are Arizona, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Democrats should also keep an eye on Minnesota and New Hampshire, where Trump came close to winning in 2016, and, depending on the makeup of the party ticket, perhaps Iowa, Ohio, and Georgia. The party must move sufficient resources to these states, and the eventual nominee must campaign energetically in them—unlike Clinton, who failed to visit Wisconsin once in the fall of 2016.

Democrats must also be realistic enough to recognize that the makeup of the party ticket in 2020 matters. If the nominee is a New Englander like Sanders or Warren, or Joe Biden of Delaware, there’s an argument for picking a running mate like Stacey Abrams, who might help turn Georgia and North Carolina, or a Great Lakes senator like Sherrod Brown of Ohio or Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin. Both are progressive populists who in 2018 easily won competitive races in states where Trump prevailed in 2016.

The whole point of any Electoral College strategy for the Democrats has to be exciting the base sufficiently to tip the balance in closely divided states. In his Democracy Now! interview, Moore argued that in light of their advantages among women, people of color, and young voters, Democrats need to “make sure we don’t give them another Hillary Clinton to vote for.”

Moore speaks with the bluntness of someone who has spent a lot of time thinking about how to win the electoral votes in battleground states. He knows that states like Wisconsin and Michigan are exceptionally polarized, not simply over Trump but also because of state-based fights in the 2010s over everything from labor rights to public education and environmental racism. Democrats won’t win these pivotal states and their electoral votes by trying to swing the handful of people who are in the middle. They’ll win by mobilizing voters, especially young people and people of color, who may have backed third-party candidates or stayed home in 2016. “Will they come out and vote for a centrist, moderate candidate? I don’t think that is going to happen,” Moore said. “They’re going to come out and vote for the fighter, for the person that shares their values.”

This is the bottom line. Democrats are likely to win the national popular vote in 2020 against a president who is disapproved of by most Americans. But to win the Electoral College, they must carry battleground states where Trump remains dangerously competitive. This may not be the game the Democrats would prefer to play. But it’s the hand they were dealt by the founders in 1787, and until we finally abolish the Electoral College, it’s the hand that must be played for a win.