Democrats and the Left: A Mutual Dependency

Mass movements stoke the fires of popular discontent, but only the state can pass laws and overhaul key institutions.

Mainstream Democrats and leftists are at each other’s throats again. Senator John Fetterman denounces progressives who condemn the war in Gaza and oppose strict limits on undocumented migration. Anger at President Biden’s support for Israel spawns hashtags like #GenocideJoe and pledges to vote for Jill Stein, Cornel West—or refusals to cast a ballot at all. The broad center-left coalition that united to resist Trump as soon as he moved into the White House—and then humbled the GOP at the polls in 2018 and 2020—is coming apart. Knitting it back together before November will be difficult—but vital.

Neither side seems to have learned a basic truth from the history of American politics: Democrats and leftists, liberal politicians and radical insurgents have always depended on each other to accomplish essential, if not sufficient, ends. Movements stoke the fires of mass discontent—but only the state can pass laws and overhaul key institutions. That relationship has often been rife with mistrust and contention: Dreamers of a new moral world unavoidably clash with pols who focus on winning the next election.

But they have often been able to work together for common purposes and to oppose a common enemy. In 2024, failure to find such a modus vivendi would allow a vicious authoritarian and his reactionary party to control the entire federal government again. Victory for Trump and his partisan faithful would set back the chance to build a kinder, more egalitarian, and peaceful society for years to come. Given Republican disdain for renewable sources of energy, it would also push the planet closer to environmental disaster.

Democrats and movement activists first began to cooperate over a century ago in efforts to resolve “the labor question.” In 1919, President Woodrow Wilson asked, “How are the men and women who do the daily labor of the world to obtain progressive improvement in the conditions of their labor, to be made happier, and to be served better by the communities and the industries which their labor sustains and advances?”

Working-class radicals had made that question impossible to ignore. During the Gilded Age, many were among the leaders of massive strikes against rapacious railroad firms and for an eight-hour day. Socialists were integral to forging the two national organizations of unions—the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor—that emerged at the end of the 19th century. The first Democratic standard-bearer to embrace labor’s cause was William Jennings Bryan, whom the AFL endorsed in his unsuccessful run for president in 1908.

Four years later, unions helped get Wilson elected to the White House. There he signed some of the signature reforms of the era—from an income tax on the wealthiest Americans to an eight-hour day for railroad workers, to the creation of the Federal Trade Commission—the wellspring of anti-trust enforcement. Labor organizers willing to cooperate with Bryan, Wilson, and their fellow Democrats did have to stomach the party’s fealty to the white supremacist order. The young African American radical A. Philip Randolph devoted himself instead to promoting the Socialist Party and organizing the first Black national union.

When liberal Democrats returned to power in the 1930s, they forged a bond with leftists who pushed them, at last, to begin breaking with their racist heritage. The linchpin of this alliance was the Congress of Industrial Organizations, in which Communists and Socialists filled vital roles as organizers and leaders of such key affiliates as the Electrical Workers, the Auto Workers, and the West Coast longshoremen. Every union in the new federation welcomed African Americans as equal members; most also pressed Democrats to take a strong stand for civil rights. The battle against white supremacy, contended CIO spokesman John Brophy, was, at root, a class issue. “Behind every lynching,” he declared, “is the figure of the labor exploiter, the man or the corporation who would deny labor its fundamental rights.”

It was becoming increasingly difficult to be both an ardent New Dealer and a vocal defender of Jim Crow. By the end of the 1930s, half a million African Americans belonged to unions, an increase of more than 600 percent from a decade earlier.

In 1934, left organizers spearheaded a number of big walkouts for union recognition and higher pay. For several days, general strikes halted commerce in San Francisco and Minneapolis. A year later, the Democratic Congress responded by passing the National Labor Relations Act, drafted mainly by New York Senator Robert Wagner. Unions, it promised, would boost the economy as a whole: “The inequality of bargaining power…tends to aggravate business” downturns, “by depressing wage rates and the purchasing power of wages earners in industry.”

At a time when fascism was surging in Europe, Sidney Hillman, the socialist head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, vowed, “In the great alignment which will mean liberal forces on one side opposed to the forces of reaction, labor should take its place.” Even during the recent heyday of neoliberalism, the alliance between Democrats and organized labor has endured.

In the early to mid-1960s, left-wing activists compelled Democratic officeholders to take a stand against racism and poverty and mobilized behind the new policies they enacted. That secret socialist Martin Luther King Jr. and such SNCC workers as John Lewis and Fannie Lou Hamer thrust the demand for Black liberation to the front of the liberal agenda. The Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts were the fruits of their struggle. In The Other America , Michael Harrington, an outspoken socialist, eloquently revealed the extent of poverty in the nation, motivating aides to John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson to create programs like food stamps and Medicaid that at least helped reduce it.

Later that decade, radicals who were female or homosexual or disabled made headlines by asserting their precious, unfulfilled right to be respected as such both in law and the wider culture. In 1972, three years after the Stonewall riot helped birth a new liberation movement, the Democratic National Convention held serious debates about gay freedom as well as abolishing restrictions on abortion. The backing of feminists and the LGBT community would soon enable the party to present itself as a tolerant force that appealed to young, mostly secular voters in particular.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The rise of conservative movements and politicians from the 1970s on and the fragmentation between insurgent activists and liberal Democrats prevented any new alliance from forming. But a revival occurred early this century when protests against the Iraq War and the suffering of the Great Recession combined to create a fresh set of progressive movements—and to elect Barack Obama president.

In one sense, the left that thrived during the Obama years and kept growing after Trump’s election in 2016 differed from its progenitors. Unlike labor’s “new millions” in the 1930s, the Black freedom movement of the 1960s, or the anti-war movement later that decade, the newest American left rallied around no single issue that united its parts and stimulated its growth. Proponents of Occupy, Black Lives Matter, the Green New Deal, and a new union militancy applauded one another’s demands while organizing separately. Notwithstanding their diverse passions, nearly all activists agreed that decades of conservative thinking and policies, under presidents and congresses of both parties, had turned the United States into a meaner nation in which the rich invariably got their way. Equality—in all its meanings—was their common desire.

Leading Democrats warmed to these movements rhetorically, while they hedged on passing the kind of sweeping programs that activists demanded. During the fall of 2011, Nancy Pelosi, the former and future speaker of the House, said of Occupy Wall Street, “I support the message to the establishment, whether it’s Wall Street or the political establishment and the rest.”

Two months later, Barack Obama called economic inequality “the defining issue of our time…. Because what’s at stake is whether this will be a country where working people can earn enough to raise a family, build a modest savings, own a home, secure their retirement.” But the president made no serious attempt to get Congress to enact the Employee Free Choice Act, labor’s main legislative priority. At Pelosi’s insistence, he did make it a priority to pass the Affordable Care Act—a down payment of sorts on the universal coverage leftists had long advocated.

To have an African American as president also gave the new Black Lives Matter movement both a sense of hope and a target on which to train its frustrations with the slow pace of change. Some lashed out at Obama and other members of the Black elite, in and out of government, for preaching to young African Americans in poor communities a gospel of “respectable” speech and dress instead of enacting policies that would give them a good education and secure jobs at living wages.

At the same time, the enthusiasm for Obama’s presidency, which never flagged among most African Americans, did help gain the Black left a nationwide audience for the first time in decades. Organizers of mass protests could point to the gap between Obama’s rhetoric about racism and his lack of progress in combating the suffering it caused. As the journalist Jelani Cobb observed, “Until there was a Black Presidency it was impossible to conceive of the limitations of one.”

During Obama’s time in office, the most successful movement on the broad left was one with no explicit connection to class or racial equality. The LGBTQ activists who pressed for legalizing same-sex marriage managed to turn an extension of the sexual freedom espoused by cultural rebels in the 1960s into a demand for equal protection under the law. Four years after running for the presidency as an opponent of gay marriage, Obama changed his mind or, more likely, decided to help increase the speed at which the winds of politics were already blowing. In June 2015, by a single vote, the Supreme Court, in Obergefell v. Hodges, agreed, and marriage equality became the law of the land.

Although Obama’s gradual “evolution” on same-sex marriage frustrated its supporters, his change of position accelerated the pace of their victory. The president’s new stance immediately became that of his party. It helped win over Black churchgoers as well as bind most young people of all races to the Democrats—when they could be bothered to vote.

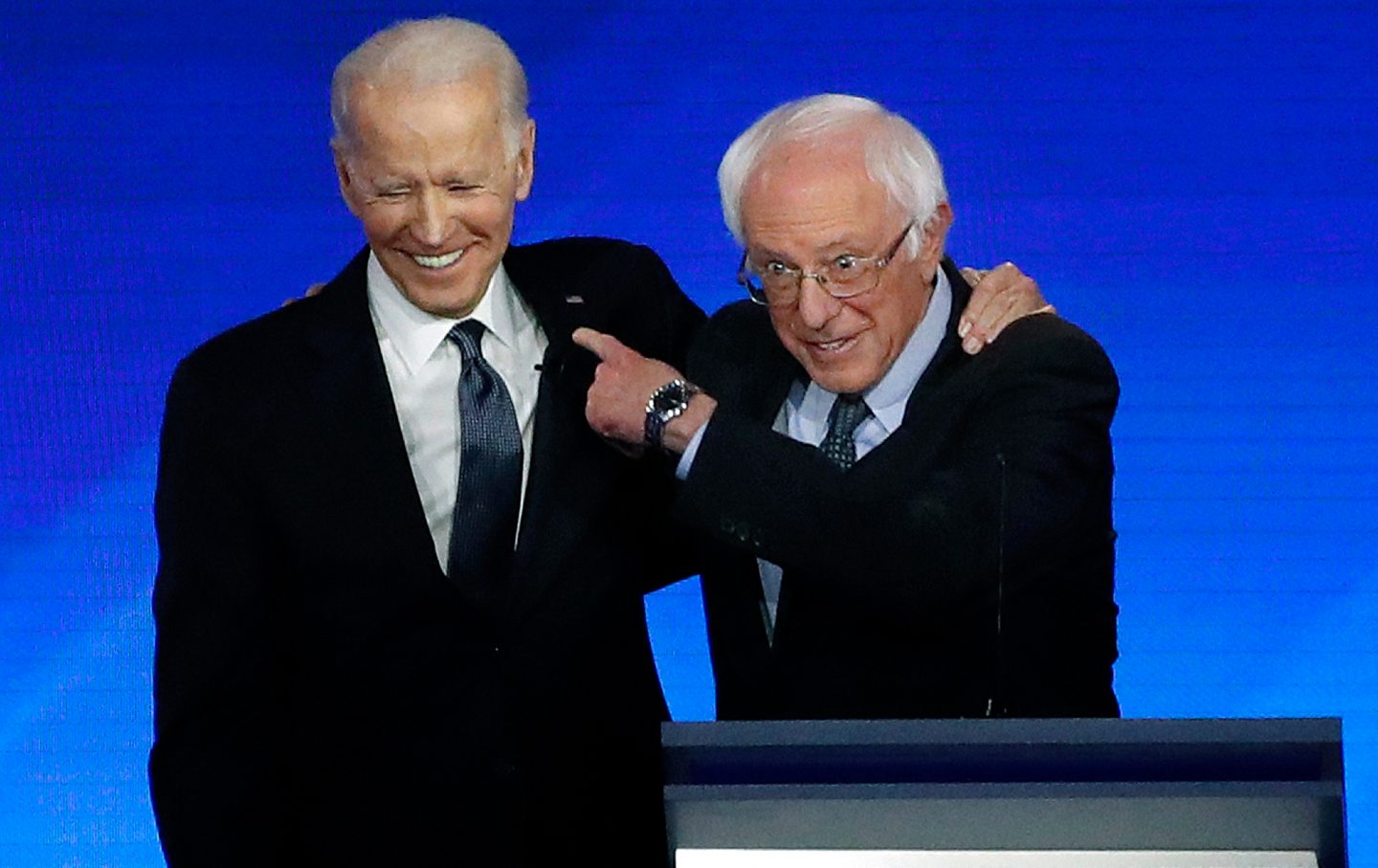

Clear evidence that a mostly young left was thriving inside as well as outside the party emerged during the final year of Obama’s tenure—in the extraordinary presidential run by an independent senator in his 70s who had often criticized the incumbent for not following through on his progressive promises. When Bernie Sanders announced his candidacy in 2015, he had already spent more than half a century advocating for an agenda that would turn the United States into a social-democratic nation—Finland with a lot more people and much warmer summers. By deciding to run as a Democrat, he infused the party with more progressive energy than at any time since the heyday of the Black freedom movement and the Great Society.

One result of Sanders’s campaign was that the party’s platform in 2016 leaned further leftward than any since the days when party leaders were proud to wear the liberal label. “More than anyone else,” commented the veteran progressive journalist Harold Meyerson, “Bernie created the current American left, but just as much, by running for president, he revealed its existence—surprising the nation, surprising the left, surprising himself.”

Joe Biden is hardly the best figure to bridge the current divide between establishment Democrats and a left that veers between disgruntlement and rage. I wish he had decided, after the midterms that went surprisingly well for his party, to bow out of the race and leave younger, more inspiring politicians to compete to take his place.

But aside from his policy toward the war in Gaza, he has accomplished more that leftists should cheer—and with exceedingly narrow majorities in both houses of Congress—than any Democrat since LBJ (who enjoyed a much larger majority in Congress). Under Biden, planned investments in clean energy go far beyond any previous legislation; the government has the power to negotiate the prices of ten popular drugs with Big Pharma and has capped the cost of insulin; and the administration is doing what it can to protect the right to abortion. No president before Biden gave such open support to strikes and labor organizing. And only the damn filibuster prevented the Senate from enacting the PRO Act, which would give workers who want a union strong legal weapons to prevent employers from denying them that freedom.

Although Democrats have been steadily losing the support of working-class voters, particularly white ones, their commitment to using the government to curb corporate power as well as empower employees has actually grown. A new scholarly article by Jacob Hacker and three other political scientists convincingly argues that both in its language and policies, “the party’s use of enhanced government spending and regulation to achieve society-wide economic goals continues to get pride of place.” Every workday, the pro-union majority on the National Labor Relations Board and Lina Khan, the most aggressive chair of the Federal Trade Commission in memory, provide evidence of that.

Of course, progressives should continue to protest Biden’s failure to restrain Israel’s deadly assault on the people of Gaza. But there is no reason they cannot, at the same time, make plans to do what they can to elect him and other Democrats in the fall. If in 1936, leftists could rally to the reelection campaign of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who also enjoyed enthusiastic support from the solid white South, their ideological successors ought to be able to campaign for a liberal president whose military aid to a longtime American ally they abhor.

Time and again, Americans in a hurry to reach the promised land have thrown up fresh ideas, challenged entrenched elites, engaged in grassroots agitation, and pushed liberals down paths they may otherwise have shunned or tiptoed along at a craven pace. While the passion of their creed sometimes blinded leftists to the exigencies of the moment, they cannot be separated from the history of American reform.

But a relentless drumbeat of cynicism and hostility directed at the Democratic Party will surely set back the momentum for progressive change. In 1976, amid another presidential campaign, the veteran organizer Bayard Rustin wrote:

Genuine radicalism…is not measured by how loud and abusively one can shout or by the purity and beauty of one’s rhetoric. Rather, genuine radicalism seeks fundamental change through concerted, intelligent and long-range commitment.… Wherever we look we can find fault. But the only result of endless fault-finding is that you end up in a corner with the few people who are as good and pure as you are…. Those self-appointed spokesmen who raise divisive issues to prove the superiority of their politics are not really radical. By confusing and distracting from the real sources of social change, they retard the struggle for equality and justice.

More from The Nation

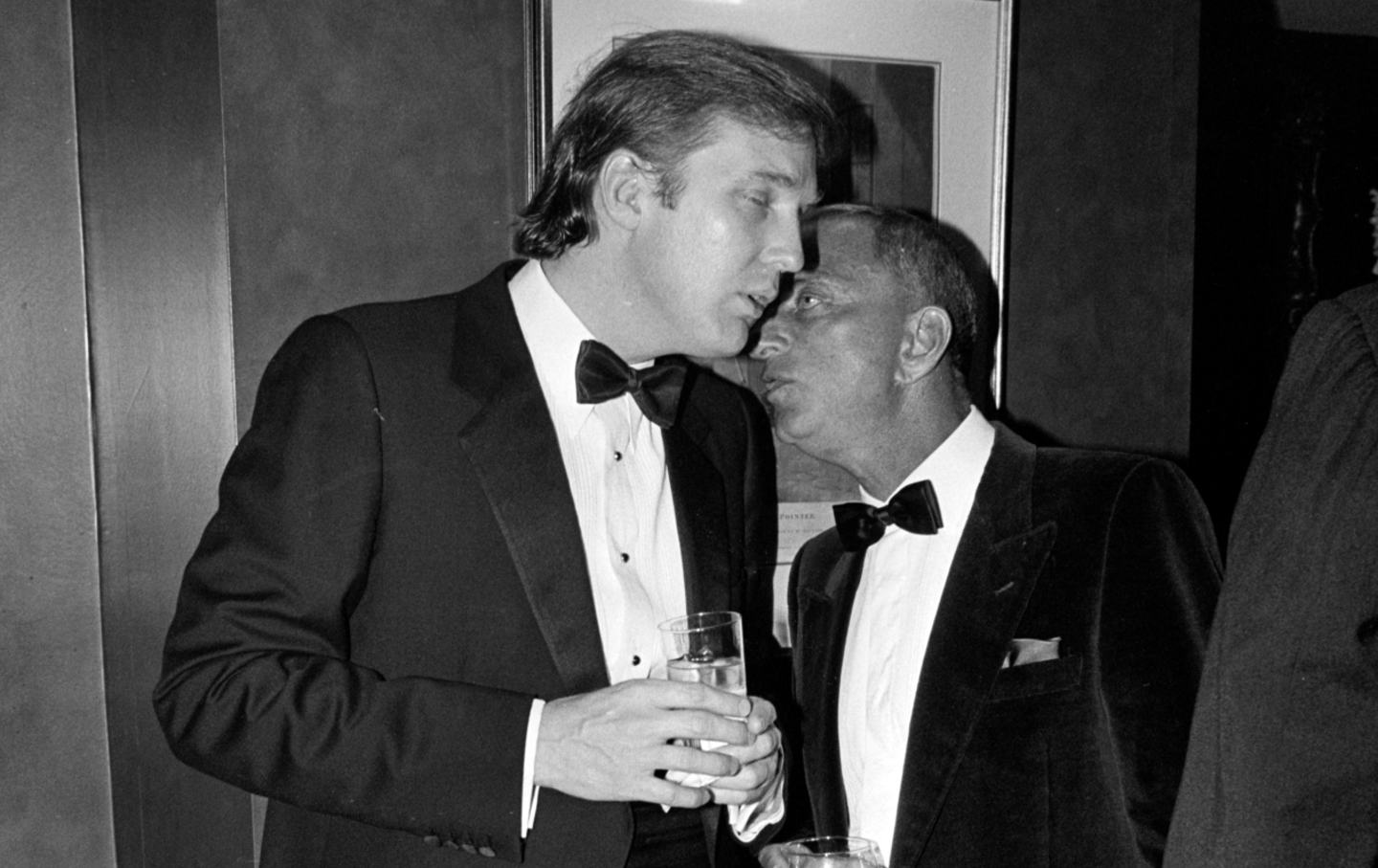

Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk

Far from being an alien interloper, the incoming president draws from homegrown authoritarianism.

If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions

The Democrats blew it with non-union workers in the 2024 election. Unions have a plan to get the party on message.

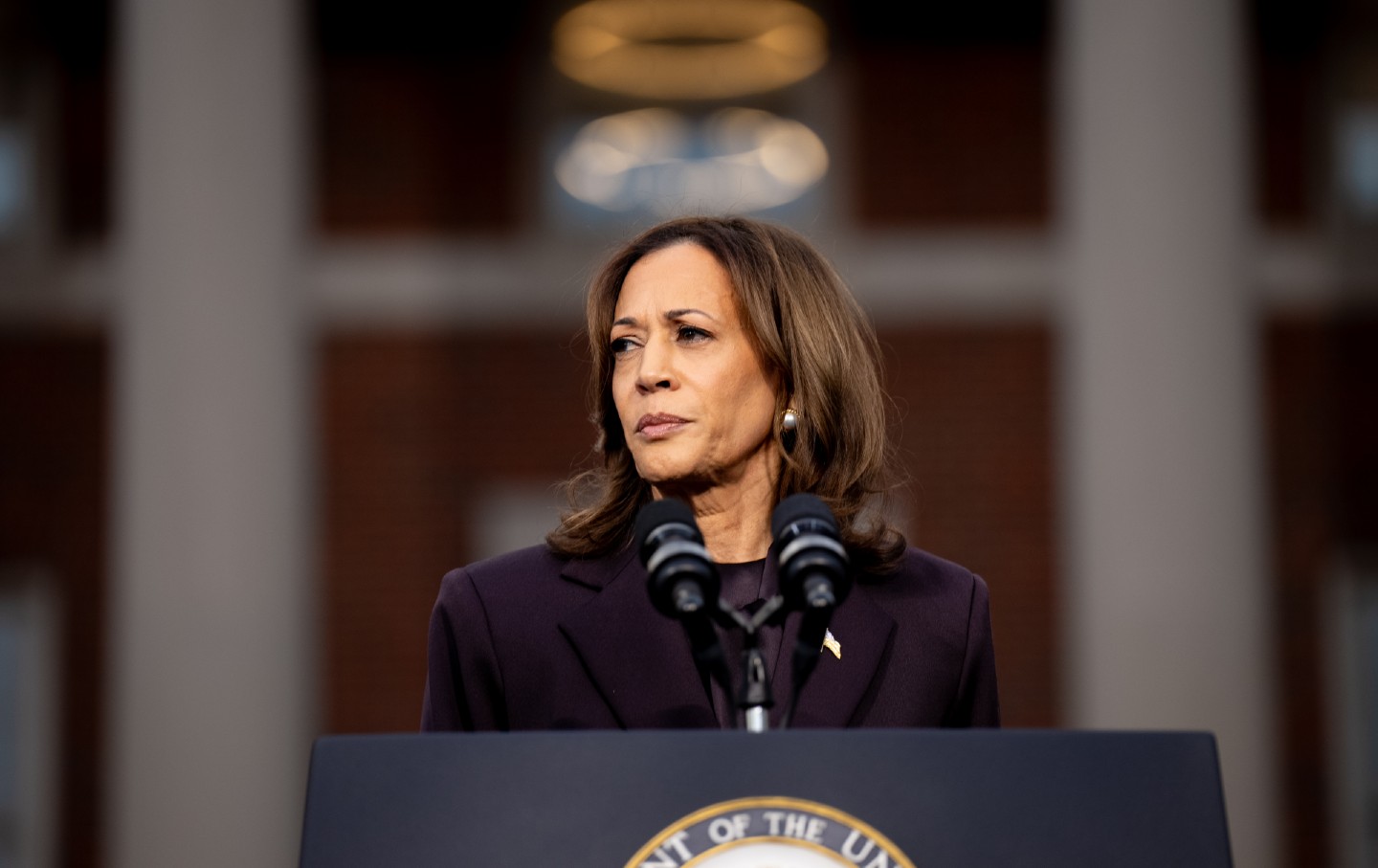

What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat? What Was the Biggest Factor in Kamala Harris’s Defeat?

As progressives continue to debate the reasons for Harris's loss—it was the economy! it was the bigotry!—Isabella Weber and Elie Mystal duke out their opposing positions.