In Ithaca, Climate Change Is Making Gentrification Worse

Revised FEMA flood maps significantly broadened risk zones enveloping the Southside neighborhood, which has provided Black residents with a sense of community for more than 150 years.

Cars submerged in flood water after a large rainstorm in New York.

(Kena Betancur / Getty)For the first time in over 40 years, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has updated its flood maps for the city of Ithaca.

The new flood map draft, released by FEMA in 2022, significantly broadens many of the previously confined flood risk zones enveloping a substantial portion of Ithaca that was not included in FEMA’s 1981 boundaries, including low-lying areas in close proximity to a large body of water.

This includes the Southside neighborhood, located along Six Mile Creek just beyond downtown, which stands as a bastion of rich culture and Black heritage and is one of the few places in the city with a density of African-American residents. Home to landmarks such as the St. James African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church—which served as a station along the Underground Railroad—the neighborhood has provided Black Ithacans with a sense of community for more than 150 years.

Increases in Ithaca’s housing and living costs however have begun to push out many longtime lower-income residents and undermine this sense of community. Just this past year, the living wage in Tompkins County made an 11 percent jump to $18.45 per hour—the largest increase seen since 2006—according to the Ithaca Voice. Yet almost 60 percent of Black wage earners in the county earn below this rate.

Rebecca M. Brenner, senior lecturer at the Cornell Brooks School of Public Policy, suggests that this new flood map could push many more residents in Southside over the edge. “This is scary to a lot of people,” Brenner told The Nation. Anticipated to take effect in mid-2024, the new map greatly expands areas of the city that are considered at risk of being impacted by a “100-year flood,” with a 1 percent chance or greater of flooding in any given year and a one-in-four chance of flooding during the life of a 30-year mortgage. Regions of the city within these “special hazard flood zones” will require many Ithacans to acquire a federally backed mortgage on their homes to purchase flood insurance who previously were not required to. “We’re expecting that when this flood map [is put into effect], it’s gonna displace people. They’re going to get forced from their homes.”

Displacement due to natural disaster insurance premiums is now a common problem in the United States, though the spotlight has largely focused on coastal cities such as Miami, New Orleans, and New York City in the face of hurricanes and rising sea levels.

Of course, Ithaca does not sit on a coastline, but FEMA’s new map furthers the argument that rising disaster insurance costs are playing an increasingly prominent role in shaping who can live where in a city.

“Unfortunately, if you look at the demographics, the more affordable properties and lower-income homes [in Ithaca] seem to be in these low-lying floodplains,” said Sally Hyot, regional flood insurance expert and retired vice president of Tompkins Insurance. According to the Ithaca Times, the number of properties affected increased by over 650 percent in this update.

According to Hyot, this new flood insurance could add an additional $2,000 to $4,000 to a household’s annual bills. Those who are unable to afford the increase may end up being priced out of their homes.

“At this point, [the Black and brown people] that made this neighborhood can’t afford to live here anymore,” said Chavon Bunch, Southside resident and executive director of the Southside Community Center. “With the numbers we got for flood insurance prices, we’re looking at $7,000 to $10,000 annually in insurance and taxes,” said Bunch. “That’s hard for anyone. I can’t imagine what these renters or people who don’t make as much are going to do.”

FEMA is typically required to review a community’s flood maps every five years, at which time the agency analyzes new local developments in land use and hydrology data, deciding whether to change or update them. The previous flood maps for Ithaca, which the city had been using for more than four decades, are notoriously outdated.

“The fact that it’s taken 40 years to get around to updating this [Ithaca] map is egregious,” according to Dr. Sandra Knight, a former deputy administrator of FEMA. “That’s too slow. And then when [FEMA] finally does take action, that’s too fast. So it’s kind of become this [lose-lose] deal. In recent years, [sparsely populated regions with no maps] have become areas of growth. And so there’s this whole game of catch-up—catching up the maps to [the development] that’s going on. And that’s not even considering the real risk of climate change issues today, much less the future.”

Approximately 22,000 communities take part in the National Flood Insurance Program, including the city of Ithaca. In exchange for making flood insurance available for all residents—which they still must pay for on their own—communities affiliated with the NFIP make a promise to follow federal floodplain management standards set up through the FEMA program.

These standards are based on the federal insurance rate maps which categorize areas by flood risk zones, with Zone A the highest risk—requiring insurance—and Zone X the lowest.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →With most of Southside now engulfed in Zone A—typically a designation for low-lying areas—FEMA’s new flood map for Ithaca will place a sudden and additional burden on the neighborhood, according to Brenner. (An interactive ArcMap GIS map can be found here.) “Whether it’s intentional or not, [Southside] has faced so much pressure from so many different angles that [this flood map] is just exacerbating,” Brenner told The Nation. “We can see a pathway to [further] gentrification because people who can afford it can go in and buy places and move people who have historically been a part of [this] community for multiple generations.”

The new flood map may only be accelerating an existing process. “This neighborhood is getting whiter and whiter, and that’s been happening for a long time,” said Ruth Yarrows, an elderly white resident of Southside. In the past nine years of living in the neighborhood, Yarrow has seen two homes on her block previously owned by elderly Black women turn over to “white folks” who could afford to buy them. “I’ve seen residents that have lived and died in this area,” said Sonya Hicks, a pastor who has lived in Southside for almost 30 years. “The home remains, but the residents no longer are African American.”

Insurance premiums will affect everyone in zones designated as high-risk, no matter their experience—or lack thereof—with flooding. Hicks finds herself in a unique situation. In all of her years of residence, her house—placed in Zone A—has never flooded. “I don’t understand how they came up with the flood map, because my house never flooded. Not once,” Hicks told The Nation. “But now, I’m in [a flood zone] according to a map that I have never seen. They never even inquired of me. Nobody ever talked to me. I don’t know anything.”

Much of the rest of my interview with Hicks was spent explaining this FEMA policy— that she, in fact, would be required to purchase flood insurance as per federal regulation. “I’m retired. What am I going to buy [insurance] with?” Hicks said. “I don’t have any additional resources where I could come up with the money. They’re asking for something that I call impossible.”

Yet the impacts in Southside are even more than financial. Displaced families are often forced to move outside Ithaca’s urbanized areas, where they lose access to essential city benefits, from walkability to public transportation. “There’s a real second-class citizenship that happens for folks getting priced out of the housing market here but still [working] jobs in the city,” said Southside resident Sarah Chalmers. “On one hand, we live downtown and we pay $10,000 a year in insurance and taxes, or we move out and don’t have anything,” said Bunch.

Though a number of solutions have been offered, they simply may not be enough to offset this displacement. In an effort to mitigate the breadth of the flood zones, the city of Ithaca has been working to build floodwalls along the creeks that are susceptible to overflowing—even more so as extreme rainfall is expected to be the most dangerous impact of climate change in the already flood-prone region.

However, there is a hole in this solution that the walls will likely not be able to fill: timing. Once the flood map officially goes into effect, homeowners will be given only 45 days to purchase the flood insurance they are federally obligated to buy through the NFIP. For those that do not comply, FEMA is within its authority to issue monetary penalties against them or put a force-placed insurance policy into effect.

Construction of the walls is expected to take three years, if not more. “There’s going to be this gap of time where people who have the financial capacity to pay for flood insurance over those years while the flood walls are being built can stay in the community,” Brenner said. “Part of what is going to gentrify and displace people is the difference between people who can and can’t float that time.”

Though the walls, once in place, will significantly reduce Ithaca’s flood risk and mitigate the need for flood insurance in a large portion of the city, for Southside, this may be a moot point. “[Building floodwalls] won’t matter because by the time they’re constructed, everyone will already be gone,” Bunch said.

Yarrow isn’t personally worried about an additional bill, but is concerned about how flood insurance will continue to exacerbate the gentrification of Southside. “I’ve bought a house in a very traditionally Black neighborhood because I can afford it,” Yarrow said. “Many people who are a part of the Black community can’t do that anymore.”

For Brenner, there is no option other than building an equitable pathway forward. Such a path would involve making sure the people of Southside are at the forefront of the discussion surrounding flood insurance in the city. “These maps are going into effect incredibly quickly and communities are going to be ripped apart,” she said. “We need to make sure that as we put policies in place that we are recognizing and involving everybody in the [Southside] community [as stakeholders] these conversations.”

More from The Nation

This Solar Panel Kills Fascists This Solar Panel Kills Fascists

New York’s Build Public Renewables Act will reduce carbon in the atmosphere, combat inequality, and help workers. It might also defeat Trumpism.

Global Burning Global Burning

The oil industry denies climate change, opposes regulations, and significantly contributes to the environmental crisis.

The “Worst COP” Concludes With a “Heartbreaking” Climate-Finance Deal The “Worst COP” Concludes With a “Heartbreaking” Climate-Finance Deal

Activists say the climate agreement effectively signed away the 1.5-degree Celsius target—”our only real chance to safeguard humanity’s future.”

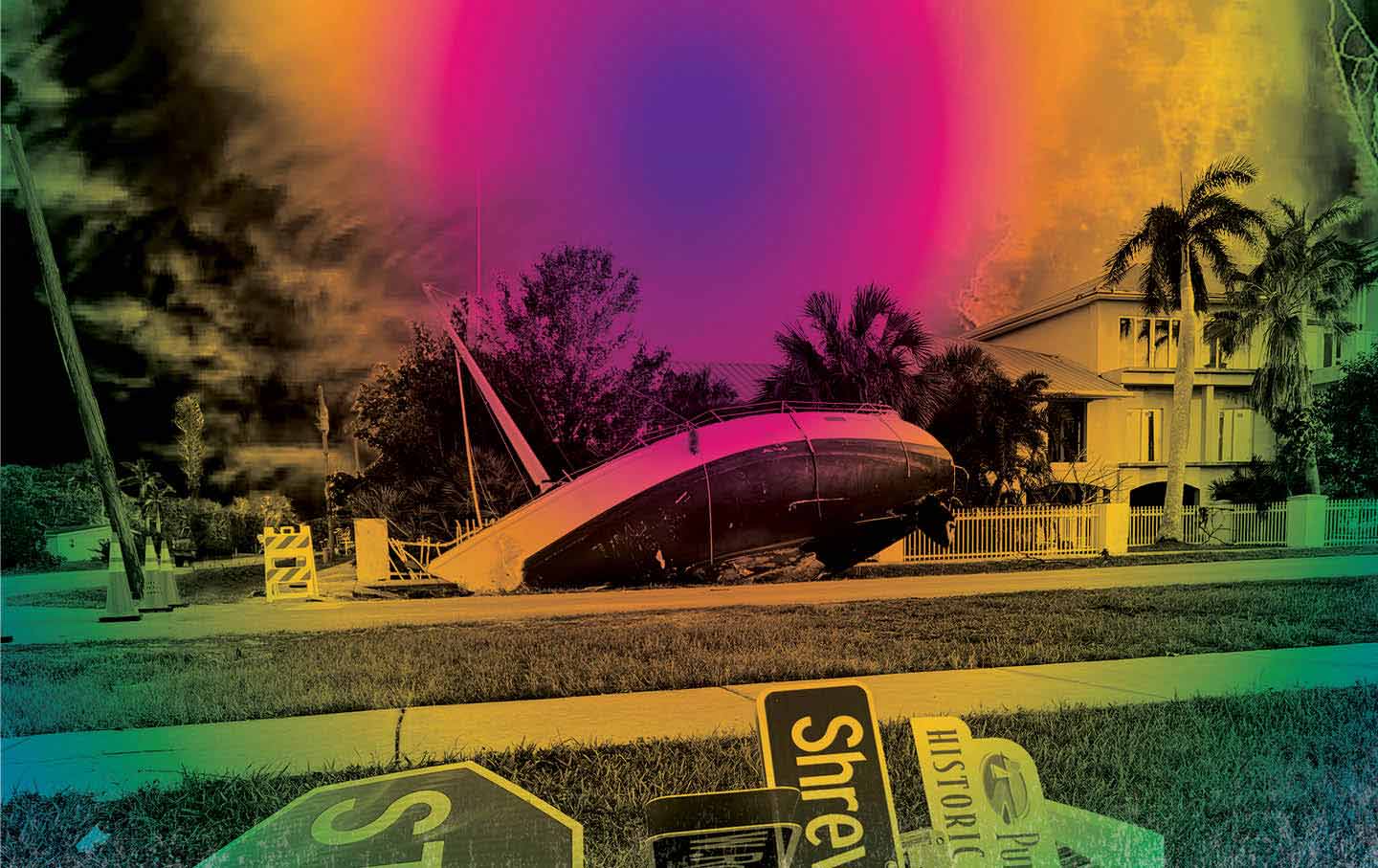

Climate Change Is the Real National Security Threat Climate Change Is the Real National Security Threat

In the wake of Hurricanes Helene and Milton, it’s clear we’re defending against the wrong perils.

Rich Countries Must Pay Up or Humanity Will Pay the Price Rich Countries Must Pay Up or Humanity Will Pay the Price

The climate activist Lidy Nacpil says the climate bill owed to developing nations is in the “trillions, not billions.”

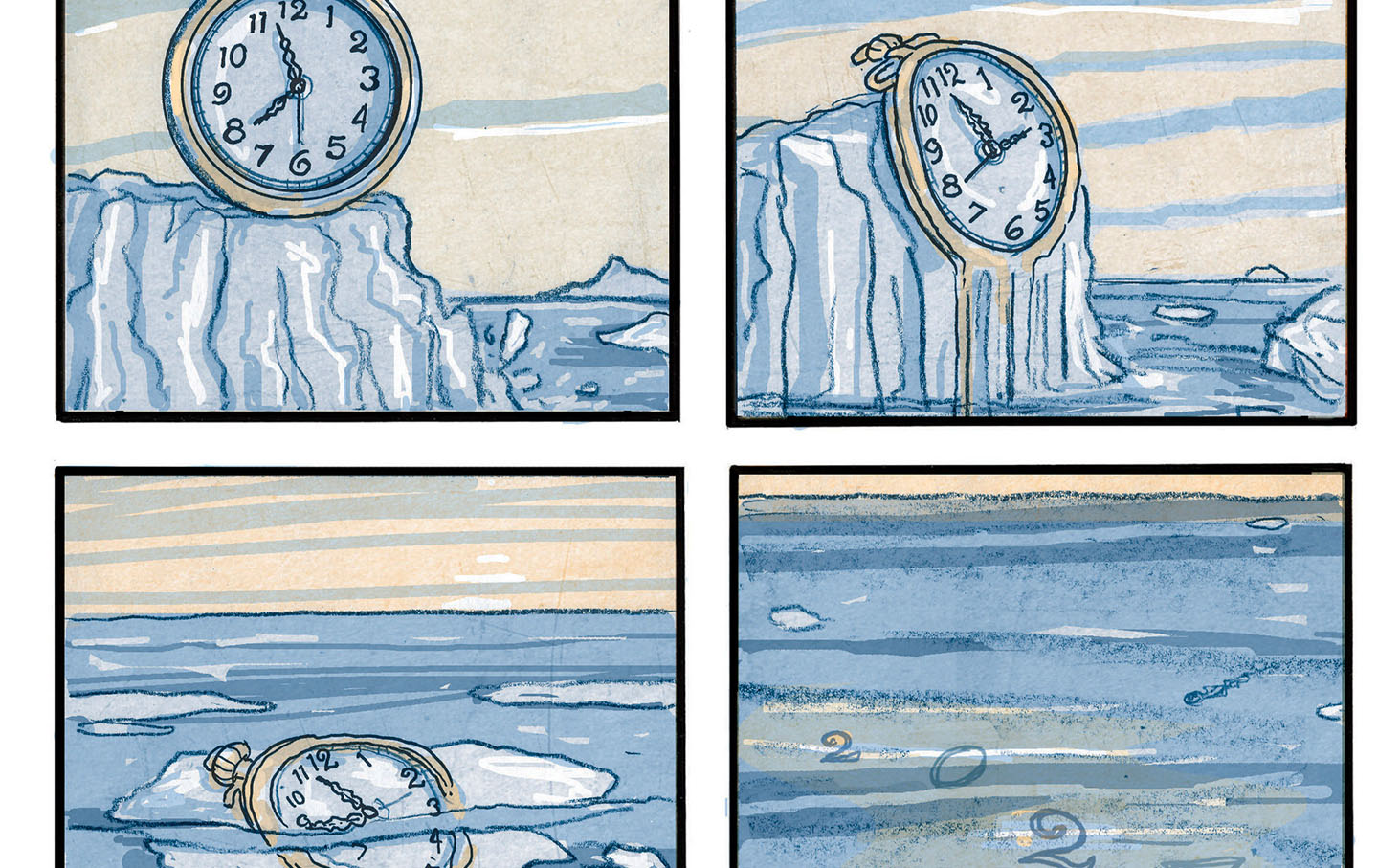

Acting on Climate Change? Acting on Climate Change?

The opportunity is melting away.