Biden Should Abolish Secretive Corporate Tribunals that Bypass the Law

A legal regime known as investor-state dispute settlements erode environmental regulation and increase fossil fuel industry profits.

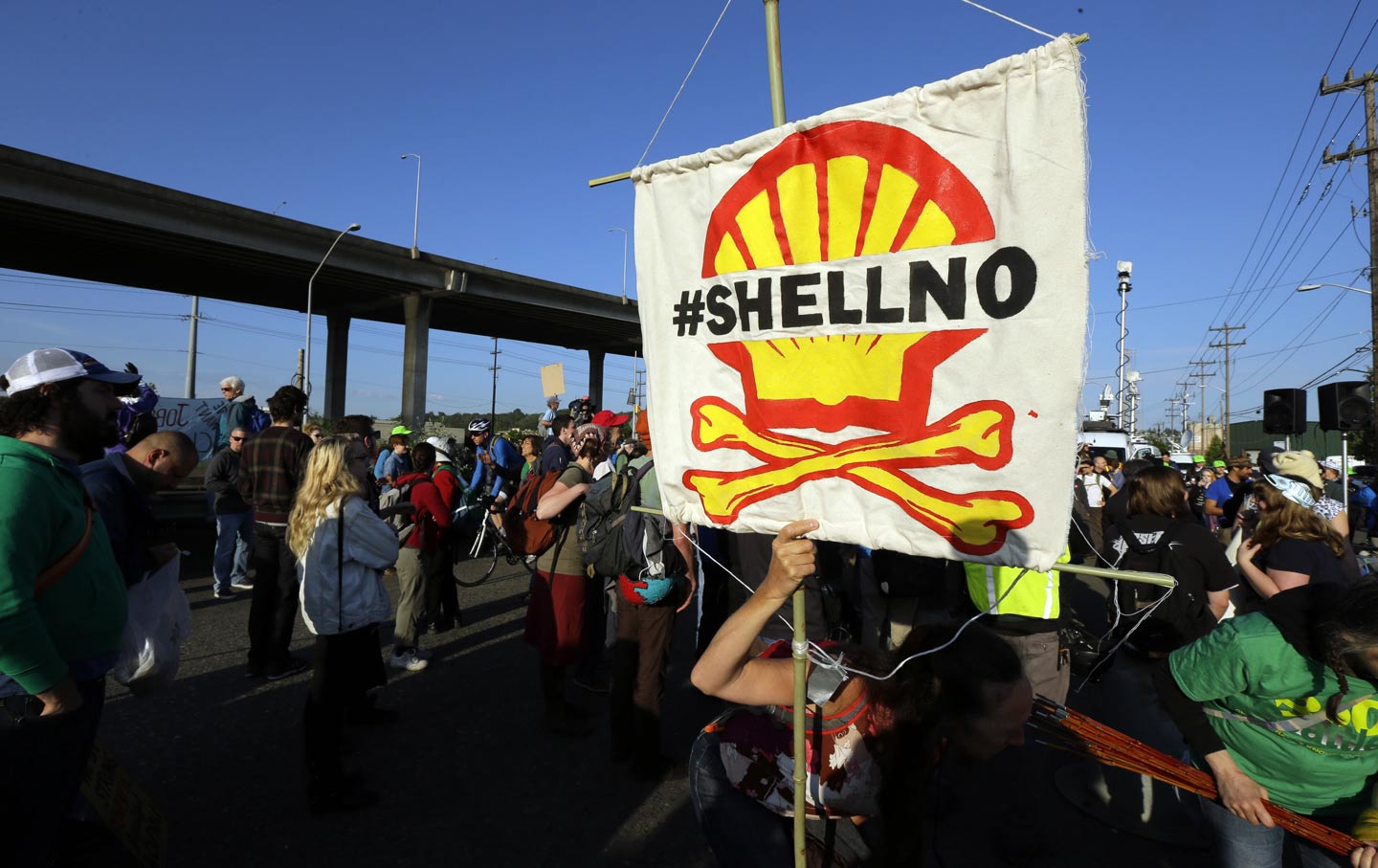

Protesters rally at the Port of Seattle, opposing Arctic oil drilling and a lease agreement between Royal Dutch Shell and the Port to allow some of Shell’s oil-drilling equipment to be based in Seattle.

(Ted S. Warren / AP Photo)For decades, international corporations have used secretive hearings to take government money and avoid environmental regulation. Known as investor-state dispute settlements, or ISDS, this regime of supranational tribunals is eroding climate protections and increasing fossil fuel companies’ profits. Now, as the Biden administration pursues its clean energy goals, the White House is facing pressure to end this little-known practice.

In November, a coalition of more than 200 labor unions, environmental organizations, and other civil society groups sent a letter to President Joe Biden asking him to bar international businesses from using ISDS to wring taxpayer money out of nations they allege are infringing on their corporate rights. Thirty-five Democratic lawmakers, led by Senator Elizabeth Warren, sent a separate letter on ISDS to Secretary of State Antony Blinken and US Trade Representative Katherine Tai.

“Your agencies have an opportunity to put an end to this system of corporate exploitation of developing countries, Indigenous communities, the environment, and workers and consumers worldwide,” the lawmakers wrote.

ISDS proceedings were designed to encourage corporations to do business in foreign countries by making it easier to settle disputes with those countries’ governments. Starting in the 1990s, ISDS clauses became a regular part of international free trade agreements. If a corporation can hold a country’s government accountable for policies that reduce their profits, the logic goes, the company will be more likely to do business there.

But climate, labor, and business transparency advocates say that corporations have abused the process, which is shrouded in secrecy. Cases are heard not by a court of law or some other public body but by a tribunal of three arbitrators picked from a list of private-sector lawyers—one chosen by the business bringing the complaint, one by the government, and a third mutual choice. It’s also a one-way mechanism, with nations being unable to bring countersuits or appeal their cases. Many of the cases remain completely private, so the public is often unaware that an arbitration ever took place. Cases can be so secret, in fact, that a body of the United Nations that tracks ISDS arbitration notes that the number of disputes filed in any year is “likely to be higher” than the numbers it has on file. If a company wins a settlement against a nation, it’s taxpayer money that gets paid out—with no cap on the amount—and settlements can sometimes demand nations pay “expected future profits” to companies.

“The whole system is set up so that it’s corporations who sue governments,” said Melinda St. Louis, a director at Public Citizen, one of the organizers of the letter from civil society groups. “If you’re interested in being part of this system, to be an arbitrator, you have every incentive to rule on behalf of companies. If you rule on behalf of the government, more companies aren’t going to bring cases. There’s a pro-corporate bias to the whole system.”

The White House has the power to change the system. One of the few revisions the Trump administration made in renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 2018 was sunsetting the ISDS clause between the US and Canada. In doing so, Trump angered many establishment conservatives. The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board, as well as several conservative groups like the Business Roundtable and the American Enterprise Institute, criticized the move, with the Journal claiming that ISDS panels “protect the property rights and contracts of North American investors.”

Giving powerful corporations the ability to leapfrog international judicial systems and keep major rulings secret in pursuit of profits may be a fair trade-off to the Journal’s editorial page. But activists warn that the potential applications of ISDS are especially dire when it comes to the climate crisis. A 2021 analysis by the International Institute of Sustainable Development of more than 1,200 publicly available ISDS cases dating as far back as the 1970s found that the fossil fuel industry used the ISDS process more than any other industry, bringing around 20 percent of all cases, and that the majority of these cases were decided in favor of investors. In 2021, TC Energy—a Canadian company that owned the Keystone XL pipeline—announced that it would be bringing a $15 billion ISDS claim against the US government after the Biden administration canceled the pipeline earlier that year.

More on climate:

“If the Biden administration is taking its climate commitments seriously, the ISDS is, as such, is certainly a threat to that,” said Matteo Fermeglia, an assistant professor of international and European environmental law at Hasselt University in Belgium. “If I were sitting at the White House, I would try to get rid of it, or at least I would try to reform it in new agreements being negotiated in a way that would allow accountability, transparency, and judicial review.”

In recent years, environmental activists and left-wing Democrats have advocated for the United States to abolish or amend ISDS clauses in international trade agreements—and so, too, have some voices from the other side of the political spectrum. While some right-wing groups attacked the Trump administration’s changes to NAFTA, other conservative groups—like the Cato Institute—have supported reforming ISDS.

“We’ve had some strange bedfellows,” St. Louis said.

The Biden administration, in turn, seems to be cautiously responsive to the idea of revising the system. The president criticized ISDS on the campaign trail, and his administration has signaled that it won’t be including the clause in new agreements it is currently negotiating. Now, advocates like St. Louis say, the administration must shift focus back to the US’s existing trade agreements and take the clause out of those.

“I think the climate crisis—in my view, at least—has triggered this [reform] process,” Matteo said. “You have had quite outrageous awards [involving energy companies].… There has been a critical mass shedding light on the system and backlash from society. The perception is that, indeed, the ISDS mechanism is at least not suited to deal with climate change issues.”

More from The Nation

This Solar Panel Kills Fascists This Solar Panel Kills Fascists

New York’s Build Public Renewables Act will reduce carbon in the atmosphere, combat inequality, and help workers. It might also defeat Trumpism.

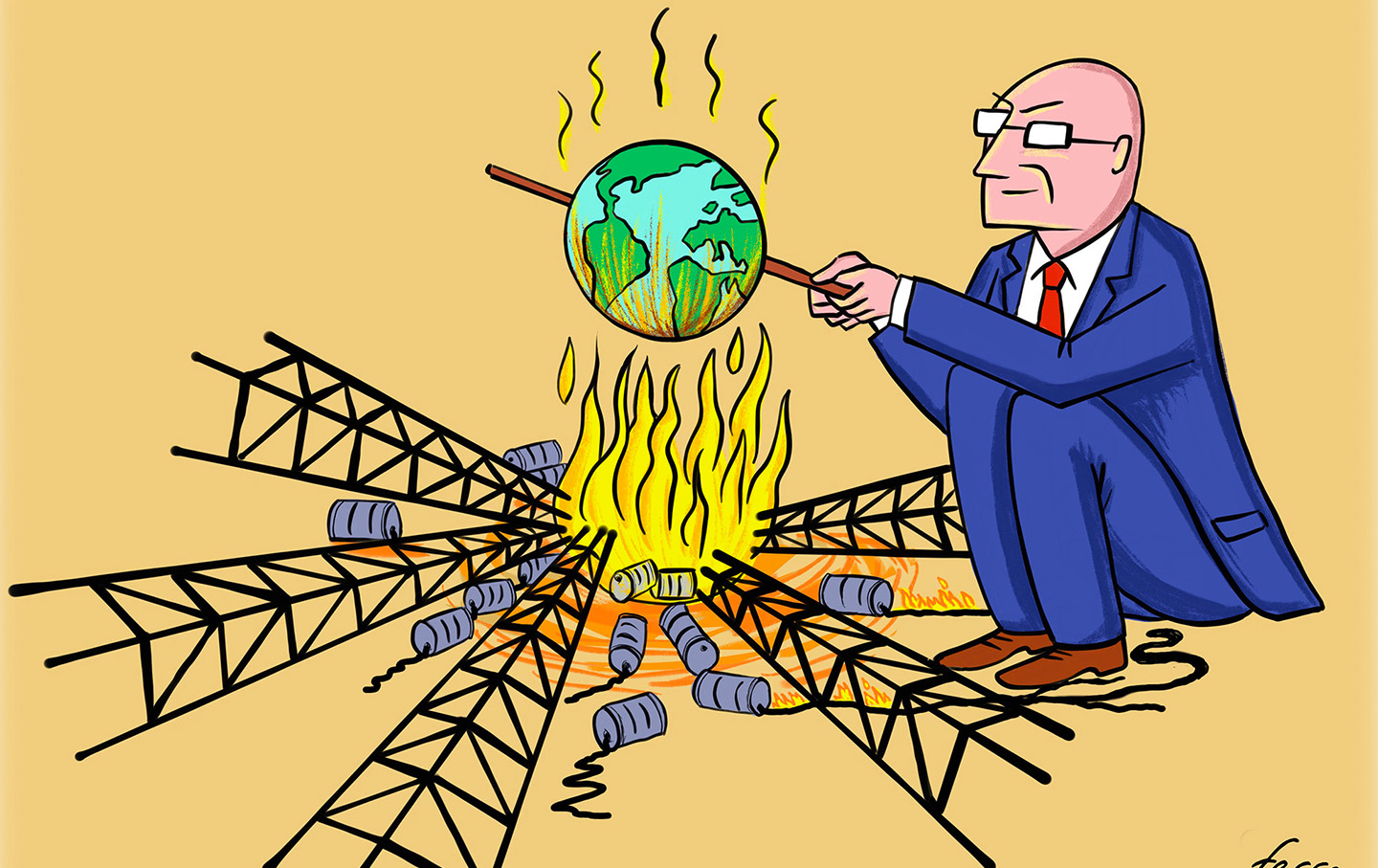

Global Burning Global Burning

The oil industry denies climate change, opposes regulations, and significantly contributes to the environmental crisis.

The “Worst COP” Concludes With a “Heartbreaking” Climate-Finance Deal The “Worst COP” Concludes With a “Heartbreaking” Climate-Finance Deal

Activists say the climate agreement effectively signed away the 1.5-degree Celsius target—”our only real chance to safeguard humanity’s future.”

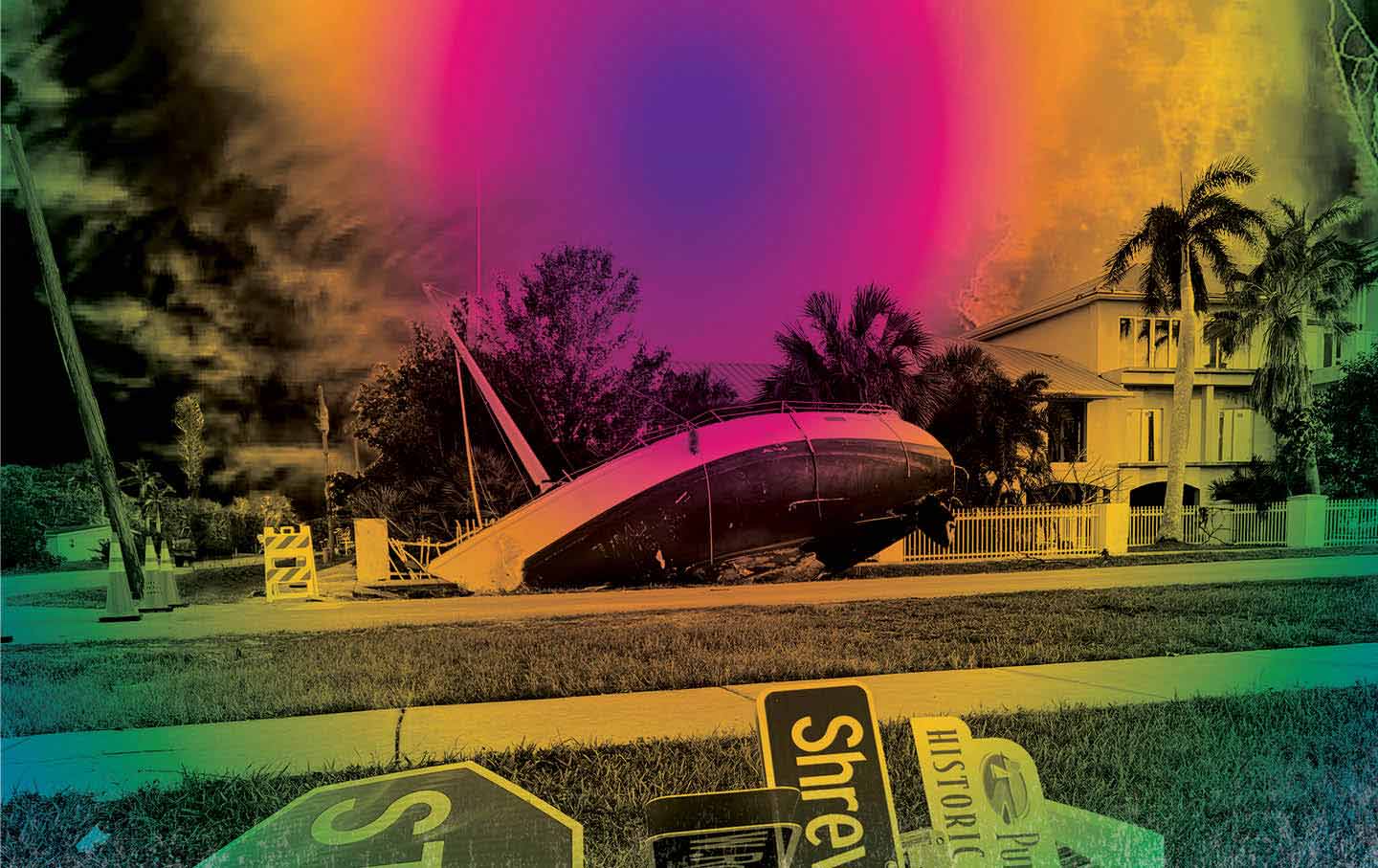

Climate Change Is the Real National Security Threat Climate Change Is the Real National Security Threat

In the wake of Hurricanes Helene and Milton, it’s clear we’re defending against the wrong perils.

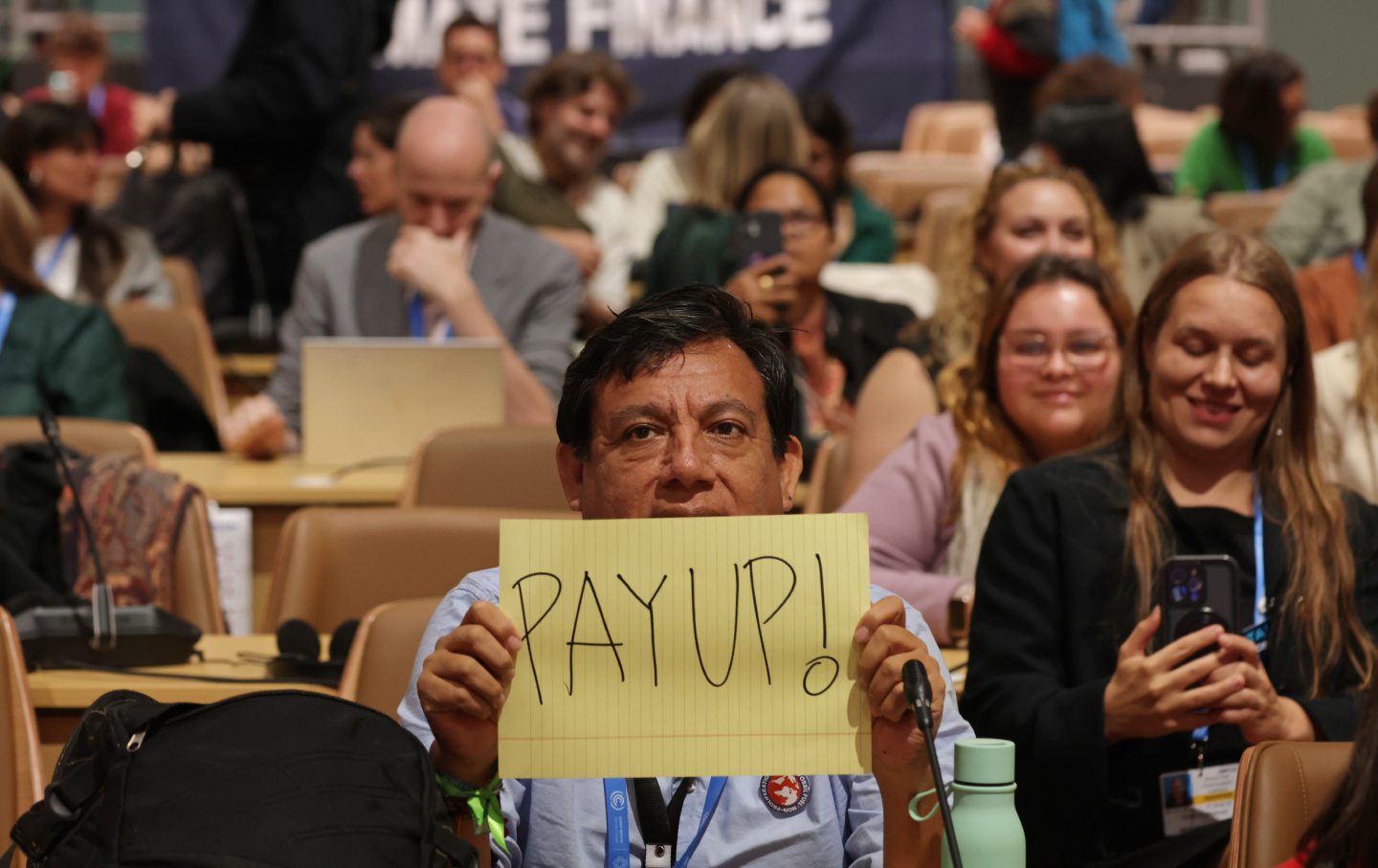

Rich Countries Must Pay Up or Humanity Will Pay the Price Rich Countries Must Pay Up or Humanity Will Pay the Price

The climate activist Lidy Nacpil says the climate bill owed to developing nations is in the “trillions, not billions.”

Acting on Climate Change? Acting on Climate Change?

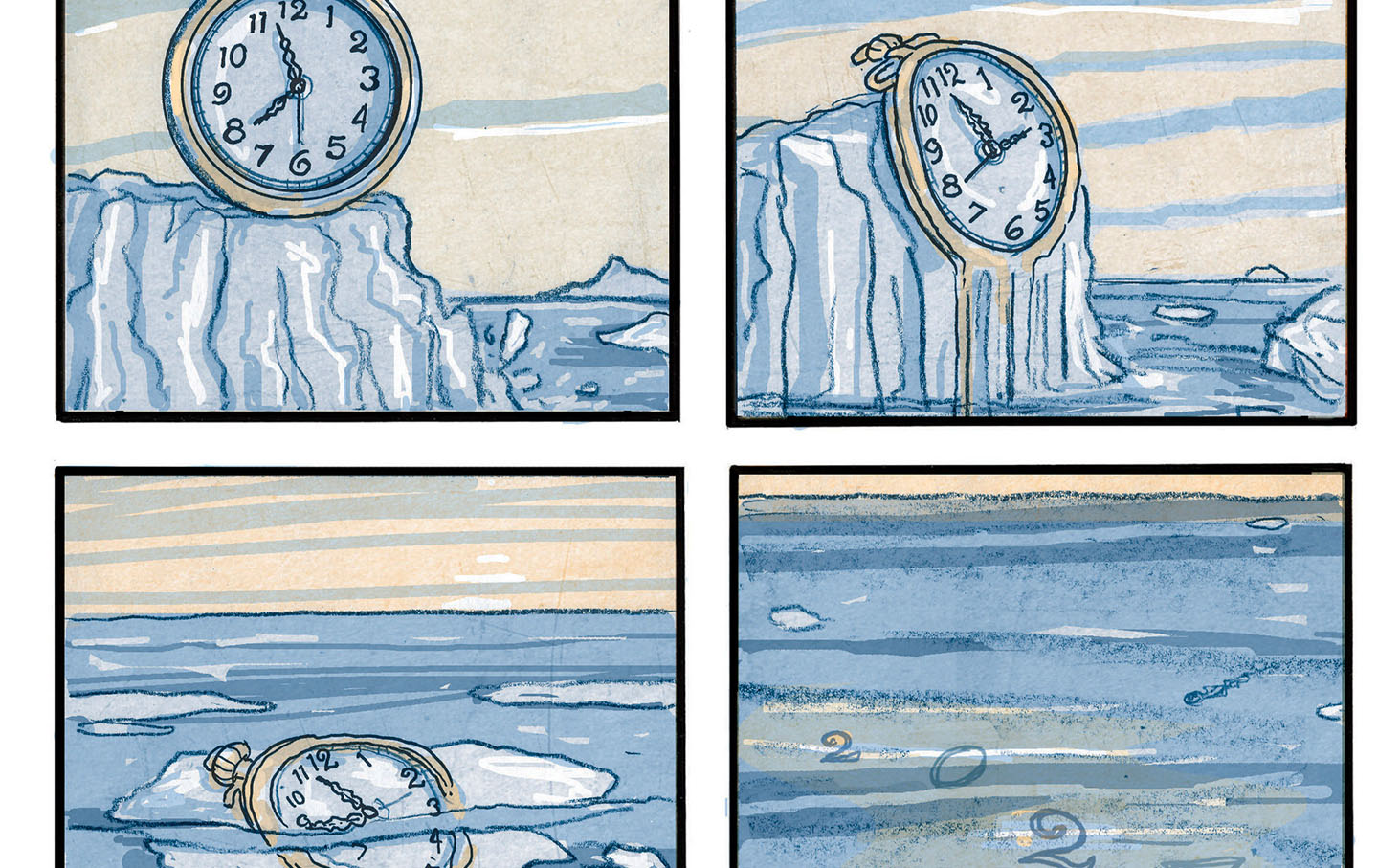

The opportunity is melting away.