Bow, N.H., September 28, 2019

On a bright, sweaty Saturday in late September, a group of about 50 determined people marched down freight tracks toward the mountain of coal that rises at the rear of Merrimack Station, the last big coal-fired power plant in New England. Dressed in white hazmat suits and singing and drumming on large white buckets—and with dozens more stationed behind them at the plant’s front gate and several hundred supporters assembled at the ball field across the street—they intended to shovel coal from that toxic mountain into those buckets, removing fuel from the fire of climate catastrophe, literally and symbolically. This reporter was among them. I wore Tyvek and carried a bucket in my hand.

Earlier, on August 17, in what the organizers called a signal action to gain attention and recruits, eight of our number had walked quietly into the unguarded rear of the plant in broad daylight and removed some 500 pounds of coal without incident. Some of it they delivered to the steps of the New Hampshire State House in Concord. The message: If politicians refuse to address the climate emergency, there are ordinary people—young and old, from diverse backgrounds and walks of life—who will.

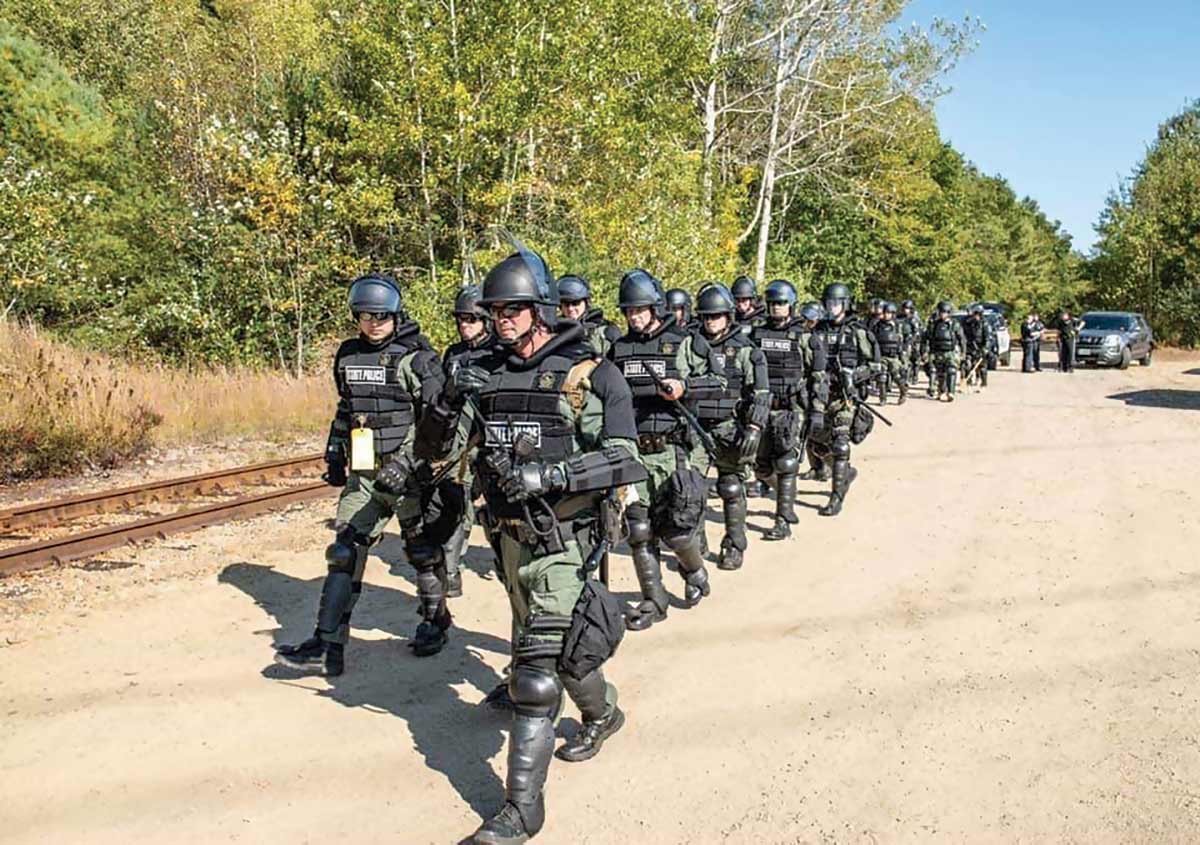

Where the tracks split off into the coal plant, the marchers were met by state and local police behind newly erected concrete Jersey barriers. We knew that if we crossed those barriers, arrest was certain. Calmly and deliberately, we gathered around, reaffirmed our collective purpose, and moved forward. Many were arrested, while roughly half, myself included, made it through the police line untouched and kept walking. A hundred yards down the rail spur, at the rear of the plant, we saw a phalanx of state troopers in full riot gear moving toward us on the double in tight formation. They carried long clubs. Their visored helmets glinted in the sun. A police helicopter hovered in the clear sky.

Sixty-seven people were arrested at the Bow plant that day. We went peacefully, as we had come. The front page of the Sunday Union Leader, the state’s leading newspaper, called it “the largest New Hampshire green action since the 1970s.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

But this was not a one-off protest. The action on September 28 marked the launch of a sustained, strategic, New England–wide grassroots campaign of nonviolent direct action. Calling itself No Coal, No Gas (nocoalnogas.org) and organized by the Climate Disobedience Center and a regional coalition of other grassroots groups, including 350 New Hampshire Action, the campaign aims to hasten the end of fossil fuel use in New England, starting with coal—and, equally important, to build a strong, unified community of nonviolent resistance, committed for the long haul.

What follows are a few of the voices in that campaign, ordinary people responding to this extraordinary moment on earth.

✱✱✱

“Our signal action, when a few of us went with the buckets and shovels—yeah, that was my first time doing any kind of direct action,” Emma Shapiro-Weiss, 28, told me. Born near Medellín, Colombia, and raised by her adoptive parents in Killingworth, Connecticut, she is a fellow with 350 New Hampshire.

“I remember we were on our way to the coal plant, and it was a very dramatic scene as you’re approaching. You see the top of the coal plant come out of the trees, and your heart drops a little bit because you know you’re headed in there and that’s the belly of the beast.

“It was a very different kind of anxiety I felt on September 28. You’re going in, like, pretty sure every single one of us is going to be arrested—and knowing you’re going to be met with such an extreme police force. But there was also a power, like, ‘We are not sneaking around. We are walking down the road. We are yelling in the streets that we are doing this.’ And they just have to watch us and then arrest us.

“I remember feeling a real sense of freedom. We are removing our consent from this system, and we are not asking for anyone’s permission.

“There’s been so much support. My local state rep came up to me and said, ‘I want you to help me get arrested.’ And I said, ‘I’ll get you to a training!’

“I definitely have the financial privilege to do this. My parents were like, ‘We will bail you out of jail.’ But I am a young woman of color, and I felt like I really needed to do it—that I didn’t want to rely on everyone else to do what I think is necessary right now.”

✱✱✱

“It was this glorious sunny day in September, and there was a weird mix of jubilation and joy and this extra sense of ‘No, this is for real,'” said Dana Dwinell-Yardley, a 33-year-old graphic designer from Montpelier, Vermont. She fell in with the Climate Disobedience Center after joining the Next Steps Climate Walk from Middlebury to Montpelier in April 2019.

“As we neared the Jersey barriers, we circled up, and there was an intensity and power in being still for a minute, listening to each other. I was surprisingly calm. There was some part of myself that’s like, ‘Dude, you should be freaked out.’ Then my friend Sonja said, ‘I want us to stop chanting and yelling. I don’t want to cross those barriers because of anger. I want to do this with love.’

“And then we just moved forward, and people helped each other over the barriers, and people were holding hands—real seriously, like, lines of people holding hands. And there was a line of, like, 10 to 12 cops, and a bunch of people got arrested, and some of us stayed with those people, and the rest of us kept walking.

“And then I saw that line of storm trooper state police coming toward us, the dust rising, and I was like, ‘This is a movie—what?’ And that was when I was scared. Those people were obviously dressed for violence. And one of the other leads had the groundedness and the brain left to say, ‘OK, let’s circle up. Let’s decide what to do.’ And I was just so grateful to that person. It was my first time being arrested.

“At first we were quiet. The state police came and surrounded us, and I was not too sure what was going to happen. There was a young woman from Maine, and she was trying not to cry. She was like, ‘I’m not going to cry in front of the cops. I’m not going to do it.’

“And we all said some encouraging things to each other, like, ‘Remember why we’re here.’ And then it was silence, and there was this awkward moment, like, ‘Am I just going to stand here and wait to be arrested?’ And so I started singing—that was the thing I knew how to do. And I didn’t sing very well. My voice was cracking. I was afraid. But it was, ‘We just have to keep doing this. This isn’t about being a beautiful singer.’ It was just about—’staying alive’ is too dramatic—reminding ourselves of being alive and being humans and feeling love and feeling conviction and staying in that part of ourselves.

“I colead a women’s singing circle on Tuesday nights, and I kept thinking, ‘Oh, I’ve been practicing for this day for so long without knowing it.'”

✱✱✱

“It was so crystallizing,” said Jay O’Hara, 37, a Quaker from Cape Cod now living in Portland, Maine, and one of the founders of the Climate Disobedience Center. “We have a giant dinosaur of a coal plant, this 19th century technology, and there are literally troops of riot police armed to the gills, with helicopters and ATVs, protecting an enormous pile of coal. It is absurd that in 2019 we are using a quasi-military force to protect a pile of fucking coal.

“It’s great that people are in the streets, that people are lobbying, that people are protesting at their capitols. Those are all critical parts of a fully blossomed movement ecology. And yet there’s something unique about going into the belly of the beast and being able to point out the failure and complicity of our economic and political systems. And we don’t have to look any further than the array of state power that was on display in defense of this enormous pile of coal.

“The work of a direct action campaign is to create that moral clarity.”

Hooksett, N.H., December 8, 2019

Winter arrived, and the campaign entered a new phase, focusing on the freight trains that resupply the Bow plant. The plant runs only a few weeks per year, producing less than 1 percent of the region’s electricity, but its owner, Granite Shore Power, will receive “forward capacity payments,” or subsidies, of more than $188 million from 2018 to 2023, with the costs passed along to ratepayers. In November eight US senators from New England, including Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, sent a letter to ISO New England, the regional grid operator, stating that its market rules appear to favor the fossil fuel status quo.

On December 7 and 8, a freight train bound for Bow, 80 cars long and carrying 10,000 tons of coal, was stopped three times by protesters (following standard railroad safety protocols) in a series of rolling blockades—at West Boylston and Ayer, Massachusetts, and at Hooksett, New Hampshire—resulting in 24 arrests and many hours of delay. At Hooksett, south of Bow, two experienced young climbers positioned themselves on a railroad truss bridge over the Merrimack River, with dozens of supporters on the tracks and the adjacent pedestrian bridge. Temperatures were in the single digits. The blockade held for more than five hours before the climbers surrendered themselves—peacefully. They were charged with trespassing and resisting arrest.

✱✱✱

“We were up there on the bridge for several hours, just me and Johnny,” said Leif Taranta, a 22-year-old from Philadelphia who is a senior at Middlebury College and a rock-climbing instructor. Last fall, they (Taranta identifies as transmasculine nonbinary and uses “they” pronouns) studied at the Autonomous University of Social Movements in Chiapas, Mexico.

“Sometimes it was very beautiful. There were these pigeons, and they would fly around us, all lit up by the sun, and there was the river below, and it was all icy. It was quite beautiful, like the sun on the railroad beams, which were all rusty and glowing red.

“And everybody below, our supporters, were singing the whole time, which was lovely, because there were also a lot of hecklers on the pedestrian bridge, shouting things like, ‘Don’t be a wuss. Just jump!’ Or telling the cops to turn the fire hose on us or to teargas us or shoot us. They kept saying that we should die.

“I’ve been thinking about how do you talk to people who are against you but not your enemy? Like the hecklers—I was so angry. But I was like, ‘You are not my enemy. This plant is hurting you. I’m doing this for all of us. I don’t want to hurt you at all.’

“There’s a lot of desperation in the world right now, and sometimes when someone sees someone else doing something powerful and hopeful, that’s really scary.

“We are all individuals tied up in these systems, and we’re just saying no to them. And that’s hard, and it’s dangerous to the system, and it’s sometimes dangerous to ourselves, and it takes a lot of practice. So I hope some people see what we’re doing and are like, ‘Wait, I can remove my consent. I can say no.’ Because, yeah, we’re all tied up in it.

“This whole thing is about being honest with others. And it’s also about being honest with ourselves and with each other.”

✱✱✱

“When Leif and I were up on the bridge after the rest of our group had been taken away, the cops and the firefighters used a lot of psychological tactics,” Johnny Sanchez, 24, told me. A grad student in sustainable agriculture at the University of Maine, he grew up on the Ohkay Owingeh Reservation in New Mexico, near the Rio Grande—the waters of which he has seen diminish dramatically since he was a child.

“This one guy, who quote-unquote came up to ‘rescue’ me, at one point looked up at me and was like, ‘What’s your name?’ And I said, ‘Johnny.’ And he said, ‘Johnny what?’ And I said, ‘Sanchez.’ And he said, ‘Good—I want someone to be able to tell my kids what your name is if I die rescuing you.’ Things like that, really trying to shake us.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to have skin in the game when it comes to climate change as a global catastrophe, because that’s what we’re facing. I think that everyone has skin in this game, whether you’re an activist or a politician or a police officer or, you know, a train conductor. And it’s important to think about the people who either don’t know that they have skin in the game or who choose to ignore it.

“And even though all these cops and firefighters are saying these pretty terrible things to us, I hope that they realize we’re fighting for them, too.”

Ayer, Mass., December 7 and 8, 2019

Saturday, December 7, dawned clear and very cold in Ayer, a modest, picturesque town 35 miles northwest of Boston and proud of its railroad heritage. That morning, some 25 eager souls arrived at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church—a small, historic parish a good stone’s throw from the freight tracks—whose priest had offered its space as shelter for the blockaders. A quarter-mile south down the freight tracks is a small rail yard, through which the north-bound coal train would pass at a crawl.

I was the lead organizer of the action at Ayer. We spent a long day and sleepless night in the church, waiting for word that the blockade in West Boylston, just north of Worcester, had succeeded—and then that the train was moving north again. It wasn’t until 3:40 am on Sunday, standing in the snow along the tracks with my fellow scout and flagger, numbed by the single-digit cold, that I placed the emergency call that stopped the train as it pulled out of the yard and then ran to get in front of the engine. On the tracks, my comrades’ faces shone defiantly in the blinding lights of the train. Twelve of us were arrested and taken to the Ayer jail.

✱✱✱

“I think I was the first one at the church in Ayer,” said Alyssa Bouffard, 32. She grew up in Marlborough, Massachusetts, and now lives in Medford. Last summer she got involved with Extinction Rebellion but is still exploring, helping form an affinity group with the No Coal, No Gas campaign.

“People started showing up from all these places, and everyone was so open and welcoming and positive, even though what we were doing was in the face of something so upsetting.

“That day and night, there was so much waiting and waiting and then sleeping but not really sleeping. We had gone to try and sleep in the church sanctuary and woke up when we got a message that the train had started moving from Worcester. OK, this is really happening. Get your stuff together. Put your vests on. And then we got a message saying, ‘This is it! Let’s go!’ And everyone just booked it out the door, and we were just going up the tracks, and it was freezing and it didn’t matter.

“Those train lights are bright. Not being able to see the person in the train and wondering, ‘Are they mad at us?’—it felt a little weird. Like, ‘OK, this is a really big train, and we’re not that many people, but we’re stopping it, and we’re holding it.’ It felt good, like, ‘Whoa, the train is stopped.’

“I feel like, yeah, I’m willing to stand in front of a coal train, because what do I have to lose right now? I don’t care what they do to me. Like, this is necessary. And yeah, I think I’ve moved from being so sad that I can’t even function to like, ‘What the fuck? This is absurd.’ I can’t just sit by and watch it happen anymore. We have to do this. This is what needs to be done.”

Harvard, Mass., January 3, 2020

After an attempt at another blockade in West Boylston on December 16, when the railroad recklessly refused to stop the train despite an emergency call and multiple flaggers [see my report for TheNation.com, December 20, 2019], the campaign regrouped with a successful blockade on December 28 in Worcester. The police arrived quickly and arrested 10 blockaders, after which the train continued on its way.

On the night of January 2–3, the campaign escalated. Previously it carried out only soft blockades—that is, people standing on the tracks using only their bodies. This time, on a wooded stretch of track in Harvard, south of Ayer, blockaders erected a 16-foot-tall, three-level metal scaffold onto which four of them climbed, prepared to stay. Those three men and one woman, ages 21 to 50, kept the train at bay for eight hours before being “rescued,” handcuffed, and taken to jail. All four received a felony charge. Boston TV news crews flocked to the scene. This time a network helicopter hovered overhead.

✱✱✱

“I was up on the scaffolding, and the cops rolled up, and the first one there looked up at this structure and was like, ‘Oh, my God—uhhh, what are we going to do now?'” said Tim DeChristopher, 38. A climate dissident with deep experience in nonviolent resistance, DeChristopher cofounded the Climate Disobedience Center in 2015 and now lives in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

“I felt like, ‘OK, now we’re in a position of some leverage.’

“One of the firefighters, the first thing he said when he walked up was, ‘Wow, they actually took the time to set this thing up right.’ I appreciated that statement. I kept trying to emphasize that the situation was safe with us up there—no one was in physical danger—but that to get us down potentially could increase people’s physical danger. And at one point, I was talking about public safety, and one of the cops said, ‘But we also have a responsibility to protect private property, and you’re blocking this trainload of coal.’ And I said, ‘Well, is there a ranking of priority between protecting the safety of human beings and protecting private property?’ And he said, ‘Yes, the safety of human beings always comes first.’ And so I kept saying, ‘Why can’t you just leave us up here in the name of public safety?’ ‘Well, we just can’t do that.’ Ultimately, the chief made the call to prioritize the profits of the coal industry and the railroad.

“I think the further we get into the climate crisis, eventually we will reach a point where people are not going to be scared out of trying to defend a livable future for themselves and the people that they care about. Where there’s no jail sentence that’s going to get people to just go quietly to their own destruction, and where the power of the state can no longer make people compliant. With every passing year, with every new wildfire and hurricane, it becomes more and more insane to think that people are just going to give up or back down and allow this to continue on the path that it’s on.”