Did We Get the History of Modern American Art Wrong?

The standard story of 1960s arts is one of Abstract Expressionism leading into Pop Art and minimalism. A Whitney show proposes an altogether different one centered on surrealism.

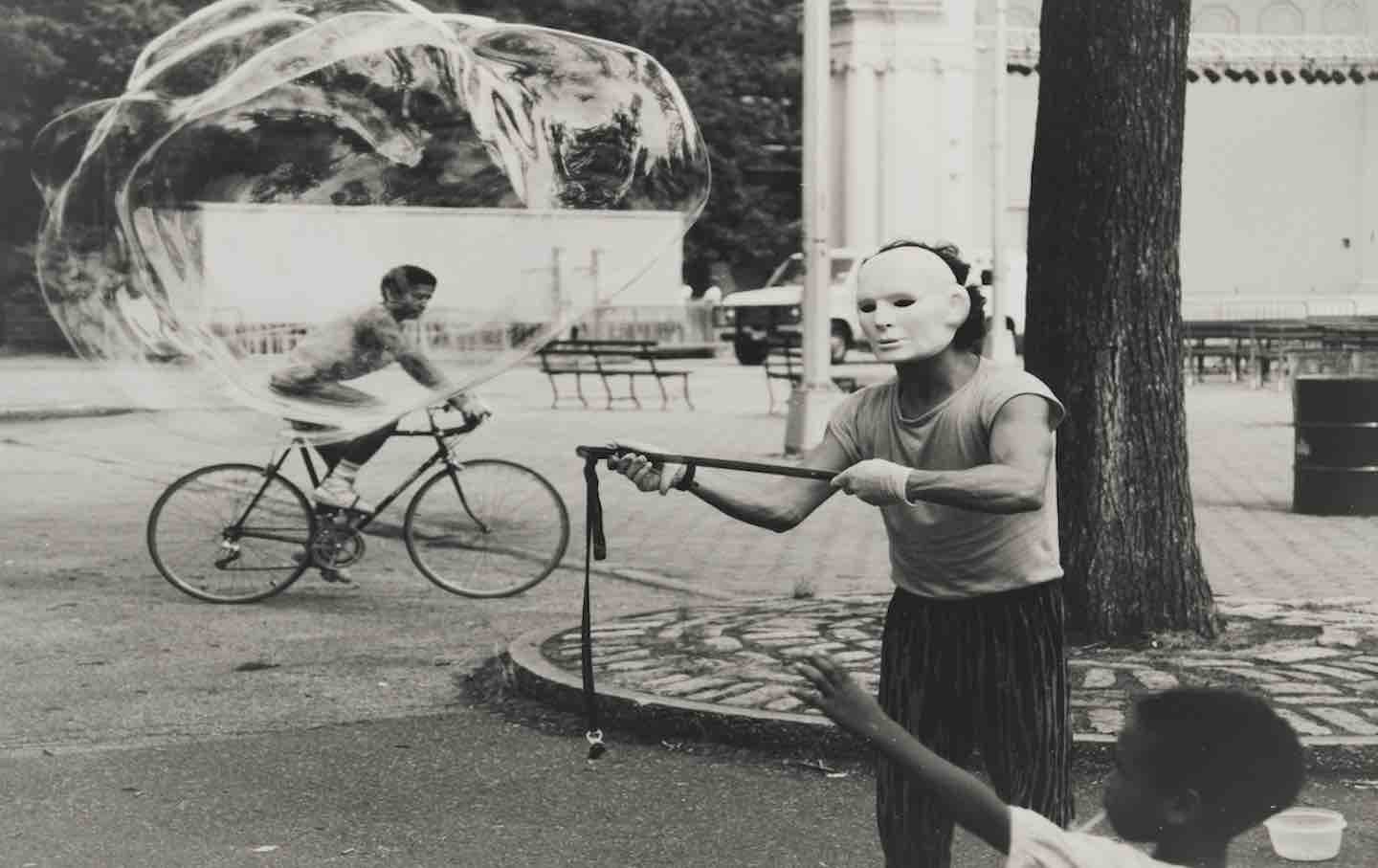

Shawn Walker’s Man with Bubble, Central Park (near Bandshell), c. 1960–79, printed 1989.

(Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art / © Shawn Walker)There’s a standard story about the development of American art in the 1960s that retains an almost biblical authority in some circles. It begins at the end of the 1950s, when Abstract Expressionism’s power began to fade, which led to the ascendance of the so-called Neo-Dada of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg as the most vital force at the start of the ’60s. And then, in quick order, Pop Art emerged around 1962 and Minimalism around 1964, which in turn begat Conceptual Art around 1968. It’s a story about the progressively more rigorous and reductive analysis of what the art object is or can be. At a bit of a tangent to this genealogy, Fluxus—the name coined in 1961—was in the mix too, making art a game more than an object, but underlining the continuing influence of Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, who had also been inspirations for Johns and Rauschenberg.

It’s a nice tidy story, easy to remember. The only problem is, it leaves out almost all the art actually made in the United States (or anywhere else) in the 1960s. Of course, from a certain point of view, that’s a benefit, not a problem—it makes things so much simpler. It’s a labor-saving device: There are so many things you don’t have to look at or think about because you’ve ruled them out before even wasting a first thought or look at them. Unfortunately, it also leaves you with a fundamentally false view of history. But worse than that, it robs you of something just as important—the pleasure of being more open-minded about what art is worth taking seriously. I can’t help thinking of what Susan Sontag wrote in “Notes on ‘Camp’”: “The man who insists on high and serious pleasures’’—let’s say, those afforded by the austerity and rigor of Minimalism and Conceptual Art— “is depriving himself of pleasure; he continually restricts what he can enjoy; in the constant exercise of his good taste he will eventually price himself out of the market, so to speak.”

Over the years, the old story of the artistic ’60s has grown more and more threadbare, but no other story has taken its place—I don’t think anyone has even made much of an effort to construct one. That’s changed with the current exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, “Sixties Surreal”—not that it succeeds (spoiler alert) in promulgating a convincing new story. But at least it tries, and that’s refreshing.

The show marks the debut of the museum’s recently appointed new curator of drawings and prints, Dan Nadel. He was a surprising choice for the job, because while Nadel has considerable experience in exhibition-making, he is better known as a writer, and in particular for writing about comics and other art forms that are usually considered tangential to the interests of an institution like the Whitney. Most notably, his recent biography of Robert Crumb has been lavishly praised. Naturally, Crumb is in the show, but unfortunately without his scene of wild-eyed cartoonists and illustrators (S. Clay Wilson, Victor Moscoso). Although I agree with The New York Times’ Deborah Solomon that the exhibition “reveals the rising influence of Nadel,” it’s not altogether his show—the curatorial work is signed collectively by him and longtime Whitney curators Laura Phipps and Elizabeth Sussman as well as its director, Scott Rothkopf, whose foreword to the catalog claims credit for the show’s idea as rooted in his undergraduate thesis.

In any case, you won’t find much of the standard story, or its protagonists, in evidence in the show. Yes, there’s a Jasper Johns flag painting, effectively sidelined by being hung in an inconspicuous spot, and an Andy Warhol screenprint of Marilyn Monroe that seems out of place. (According to Solomon, these were both last-minute additions to the show at Rothkopf’s behest, on the grounds that “that the general public was more likely to see a group show at the Whitney if at least a few names were familiar.”)

The new story, according to the Whitney, is that Surrealism was a more important source for the art of the 1960s than abstraction and formalism. Such ’60s stalwarts as Roy Lichtenstein, Jim Dine, Frank Stella, Carl Andre, Donald Judd, and Sol LeWitt are absent, not to mention the younger Conceptualists who began to emerge at the end of the decade, such as Joseph Kosuth or Lawrence Weiner. Robert Smithson is present and accounted for, but with a very early, quasi-Expressionist painting, Green Chimera With Stigmata (1961), rather than the Minimalist-influenced non-site sculptures and earthworks for which he gained attention starting in the mid-1960s.

All the more surprising, then, that Rauschenberg—whose free-associational mash-ups of imagery and objects would seem inherently related to the “pure psychic automatism” that André Breton called for in the first Surrealist manifesto—is nowhere to be seen. And in a show highlighting how artists of the ’60s took Surrealism “as a touchstone and license for exploring psychosexual concerns that were anathema to the formalist critical orthodoxy of the day,” it’s incomprehensible that the radically self-revealing art of Lucas Samaras is represented only by a small and inconspicuous box construction. Strangest of all, some of the actual card-carrying Surrealists who were at work in the United States in the 1960s are nowhere to be seen—I’m thinking above all of Joseph Cornell and Dorothea Tanning, not to mention the Paris-based African American Ted Joans, who famously declared, “Jazz is my religion and Surrealism my point of view.”

The upside of these sometimes inexplicable omissions and semi-omissions is that there’s plenty of room for obscure artists and rarely seen works, as well as for some of those “artists’ artists” whose names pass like shibboleths among the cognoscenti (Lee Bontecou, John Outterbridge, Paul Thek, and H.C. Westermann among them). The show freely mixes photography and, to a lesser extent, film with painting, sculpture, drawing, and prints, and reflects a geographic range unusual in such surveys: It includes not just the usual New Yorkers but also Chicago Imagists (Jim Nutt, Christina Ramberg, Karl Wirsum), California “funk artists” (William T. Wiley), assemblagists and collagists both white (Wallace Berman, Bruce Conner, Wally Hedrick) and Black (John Outterbridge, Noah Purifoy, Betye Saar), as well as artists from farther afield; I’m always pleased to see the vivid fiberglass sculptures of the Chicano Texan Luis Jimenez, for instance. Nearly half the artists are women, and Native, Latino, Asian, and Black artists abound, including many of whom I was previously ignorant: the Chicago assemblagist Ralph Arnold, for instance, or the California fiber artist Kay Sekimachi. And photography fits easily into the mix, since the mainstream of postwar photojournalism was always a kind of veiled Surrealism. Cornell Capa had advised Henri Cartier-Bresson, “Don’t keep the label of a surrealist photographer. Be a photojournalist…. Keep surrealism in your little heart, my dear,” and in its own way a later generation of Americans, including Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander, Adger Cowans, and Ming Smith, did the same.

The result is a show that comes across as brash, lively, and a little too motley. The sense that cards are being reshuffled, the deck being redealt, is refreshing, but here that means you have to face the good, the bad, and the ugly. Not everything that would make an imaginary formalist huff “But what about the picture plane?” is inherently Surrealist-influenced—in particular, a lot of the more politically didactic work included seems far from the wilds of Surrealism—and, for that matter, neither is it inherently interesting. “Sixties Surreal” is filled with things that made me long for a more resistant, less loosey-goosey sense of their own material embodiment.

The range of work included, in fact, is so wide that it begs the question: What do the curators mean when they say “surreal”? It’s not Surrealist in the strict sense, that is, directly connected to the movement founded a century ago in Paris by André Breton—a movement, moreover, as renowned for its periodic purges and exclusions as for its range of adherents. It’s “surreal” in the everyday vernacular sense: “Like, wild, man!” The curators quote the art critic Lucy Lippard: “To most people it means anything odd, suspicious, impolite, unfamiliar, threatening, obscene, or just plain unconventional.” That’s a pretty wide-open field; what fits the description is fairly subjective, especially after a few tokes of the joints that, I hear, were being widely passed around back in the ’60s.

Consider, for instance, the first thing you’ll see as you step off the elevator: three very realistic life-size sculptures of camels, made in 1968–69 by Nancy Graves. At least to those of us who don’t encounter these enormous animals on a daily basis, they might appear to be real camels, taxidermied, but in fact they were constructed by the artist, on the basis of detailed research, out of various materials: wood, steel, burlap, polyurethane, animal skin (the species unspecified), wax, and oil paint. It’s precisely the beasts’ realism that makes it feel uncanny—surreal in that vernacular sense—to run into them here rather than in a natural-history museum. It’s an effect of displacement that owes something to Duchamp and his reframing of ordinary objects as readymade artworks. But a camel, outside its home territory, isn’t so ordinary; here, it might provoke you to reflect what a strange, irrationally formed creature a camel seems to be, as if nature herself had invented it in a Surrealist mood.

From another point of view, it’s less important that the appearance and display of Graves’s camels gives them a surreal air than that she followed, to what seems an unreasonable degree, her own idiosyncratic intuition about what her art had to encompass—though it may sound paradoxical to say so, the research project of which her sculptures were the result may have been more surreal than the sculptures themselves. Graves began working on camels in 1965–66 while living in Florence, Italy, where she became entranced by the anatomical models in the local museum of natural history, going on to devote most of a decade, according to the catalog, to “intensive historical and taxonomic research on camels, supplementing her firsthand experience with the animals in Morocco by spending days studying them and other large mammals at libraries, natural history museums, and slaughterhouses.”

Renaissance artists like Leonardo da Vinci, who saw the study of anatomy as essential to artistic representation, would have understood Graves’s fascination, but in the 1960s, this pursuit was truly eccentric, even bizarre, and should probably be understood in terms similar to those expounded by Sol LeWitt in his “Sentences on Conceptual Art” (1969), where he asserted that “Conceptual Artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach,” and that, therefore, “irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically.”

LeWitt’s emphasis on the irrational sources of art, while nonetheless calling for a systematic approach to its pursuit, is what shows that he—unlike many of the artists in “Sixties Surreal”—was a true heir of Breton and his comrades, who cultivated a quasi-scientific investigatory approach to their delvings into the unconscious. Why couldn’t the Whitney curators acknowledge that the influence of Surrealism was just as strong in an art such as LeWitt’s as it is in, say, Claes Oldenburg’s hilarious Soft Toilet (1965), which so evidently echoes both the melting clocks of what might be the most famous Surrealist painting of them all, Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931), and the bathroom function of Duchamp’s most notorious readymade, the urinal that in 1917 he dubbed Fountain. Or in Benny Andrews’s monumental painting No More Games (1970), in which a Black man gazes blankly into the distance, casting a Giorgio de Chirico–style shadow into the desolate landscape in which he sits next to the body of a (presumably dead) white woman covered in nothing but the American flag; the pinkish-hued tree stump behind, encircled by a kind of snakelike vine, appears to be an outgrowth of her left arm. Or in Harold Stevenson’s 39-foot-long painting of a nude man (said to be modeled on the actor Sal Mineo) in extreme close-up, The New Adam (1962), a paean, as the catalog says, “to the human body as a site of desire,” yet so overwhelming in scale that its “too-muchness” becomes perturbing.

The show’s general (though not complete) blindness to the surreal dimension to abstract and conceptual art is tied to the curators’ adhesion to the views of the critic Gene Swenson. Swenson was a sort of critique maudit who had a brilliant but brief career, moving—as Rothkopf wrote in 2002 in Artforum—“from being one of New York’s most influential critics to a bitter and paranoid outcast.” He applauded the arrival of Pop Art when all those who thought of themselves as serious critics were turning up their noses at it. By contrast, a few years later, he observed the rise of Minimalism and the resurgence of abstract painting with disdain, and in 1966 curated a show at the ICA in Philadelphia that asserted the superiority of a “literary” tradition, derived from Dada and Surrealism and culminating in Pop and the rather more visceral work of Thek and a few others, to the more widely accepted “formalist” tradition based in Cubism and abstraction. His 1966 show, “The Other Tradition,” attracted more curiosity than approval, and after his career suffered some setbacks, he began experiencing mental illness, which among other things led him to imagine himself as the Diogenes of the art world. Jill Johnston told the story, after Swenson died in a car crash in 1969, age 35, of “how he appeared at a MoMA opening in bare feet holding a lantern aloft and replied when asked what he was doing that he was looking for one honest man.”

The Whitney should have thought better than to take up the banner of Swenson’s anti-Minimalist, anti-abstract, anti-formalist stance, especially since its curators don’t seem prepared to sign on to the polemic, just to experimentally leave out whatever Swenson would have left out. They also put in a lot more than Swenson probably would have done: work with plenty of subject matter but no real relation to Surrealism. A tighter, smaller, more coherent exhibition would simply have revisited “The Other Tradition” to ask how Swenson’s choices hold up today. I’m not sure the answer would be that encouraging: The world has come around to Swenson’s high opinion of Thek, but on the evidence of what’s been included in “Sixties Surreal,” the other young post-Pop artists he touted—Joseph Raffael and Michael Todd—are unlikely to make a retrospectively deeper impact.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Really, the curators should have looked elsewhere for a way to understand the role of Surrealism in the American art of the 1960s. The poet John Ashbery, a widely published art critic who was disinclined to choose sides among art-world blocs—let alone to make himself the leader of one, as Swenson seems to have desired—wrote some suggestive words on Surrealism that have been too little noticed. For Ashbery, Surrealism should not be set in opposition to other modernist currents, but instead considered as “the connecting link among any number of current styles thought to be mutually exclusive, such as Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, and ‘color-field’ painting. The art world is so divided into factions that the irrational, oneiric basis shared by these arts is, though obvious, scarcely perceived.”

Ashbery was writing in response to the 1968 MoMA exhibition “Dada, Surrealism and Their Heritage,” which Swenson despised as a sanitized version of his beloved “other” tradition. What did Ashbery think of Swenson’s position? It’s hard to know. I haven’t found any mention of Swenson’s name in any of Ashbery’s writings—but he did title one of his poems (in the 1977 collection Houseboat Days) “The Other Tradition” and later gave his 1989–90 Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard the title “Other Traditions” (the lectures were published in book form in 2001). So the phrase, at least, was one the poet found resonant, even if he didn’t use it the same way Swenson had. In particular, Ashbery saw a direct line from the echt-Surrealist Joseph Cornell through Rauschenberg to “the radical simplicity of artists like Robert Morris, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt or Ronald Bladen,” going on to draw the conclusion that what makes those Minimalists’ art so effective was not what the artists themselves were inclined to say it was—not an analytical approach to the nature of the object, but rather a surrender to the uncanniness of its mere presence. Just as “Cornell’s art assumes a romantic universe in which inexplicable events can and must occur,” Ashbery asserted, so it was the case that “Minimal art, notwithstanding the Cartesian disclaimers of some of the artists, draws its being from this charged, romantic atmosphere, which permits an anonymous slab or cube to force us to believe in it as something inevitable.”

Some would see this Surrealizing interpretation of Minimalism as effectively a hostile takeover. So be it. But a show organized on that principle, rather than on Swenson’s attempt to counter formalist dogma with an anti-formalist one, would have given us a truer account of the surreal ’60s than “Surreal Sixties” has.

More from The Nation

The Scramble for Lithium The Scramble for Lithium

Thea Riofrancos’s Extraction tells the story of how a rare earth mineral became the focus of a worldwide battle over the future of green energy and, by extension, capitalism.

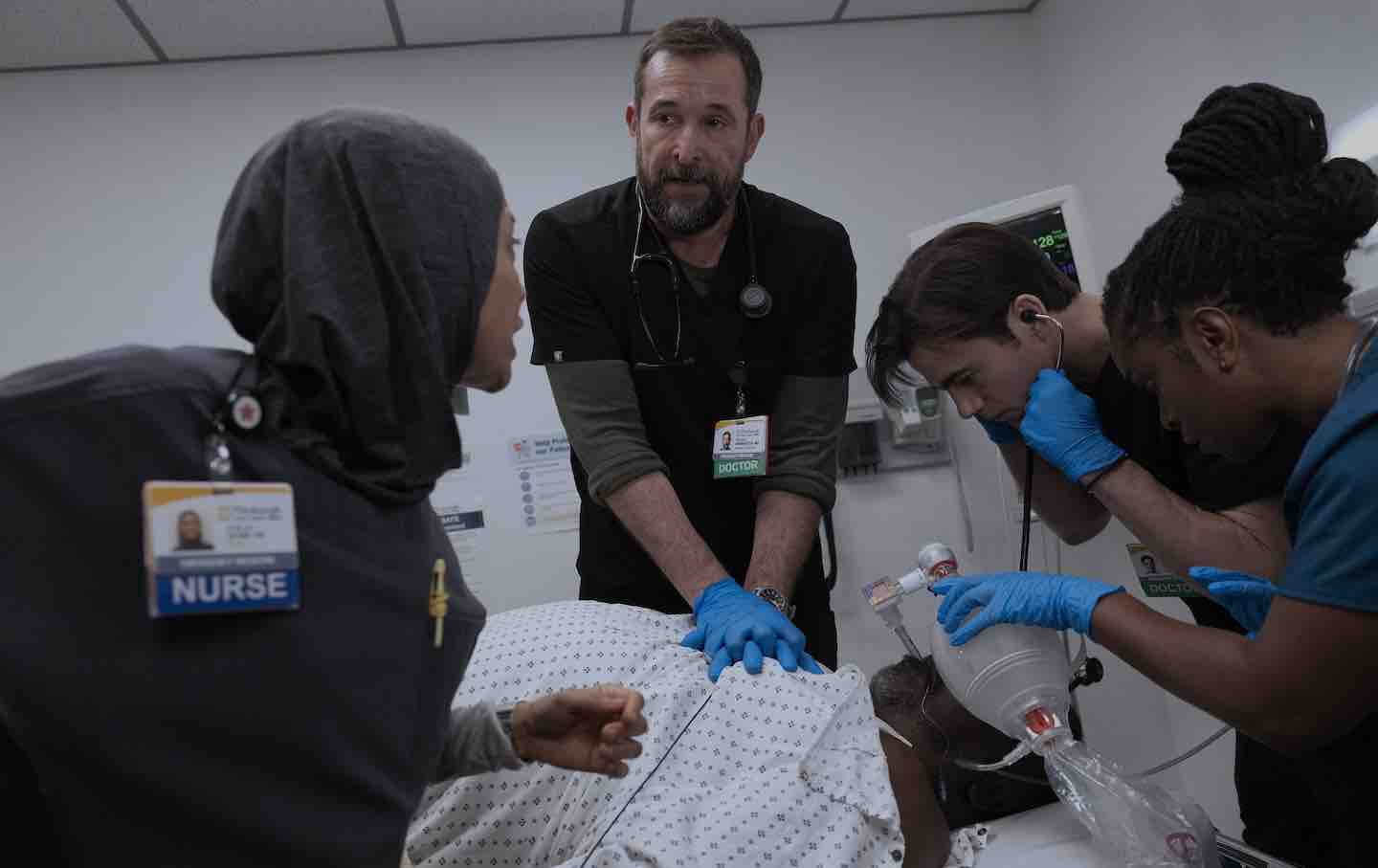

“The Pitt” Shows Doctoring Uncensored “The Pitt” Shows Doctoring Uncensored

The second season tackles everything from the role of AI in medicine to Medicaid cuts. But above all, it is about burnout.

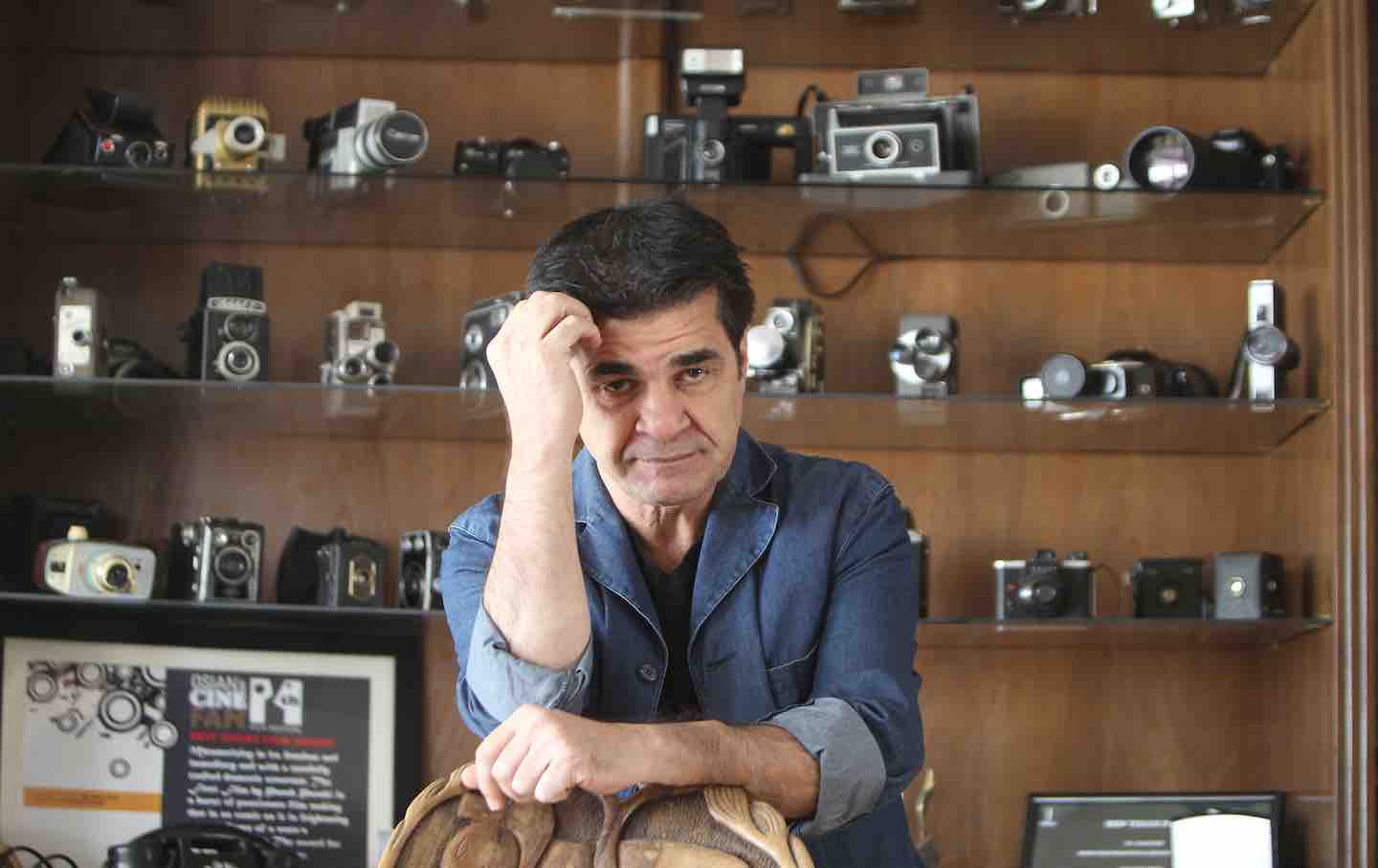

Jafar Panahi’s Scenes From a Crime Jafar Panahi’s Scenes From a Crime

His films show how a regime’s wrongdoing can upend one’s sense of self and transform the very rhythm of daily life.

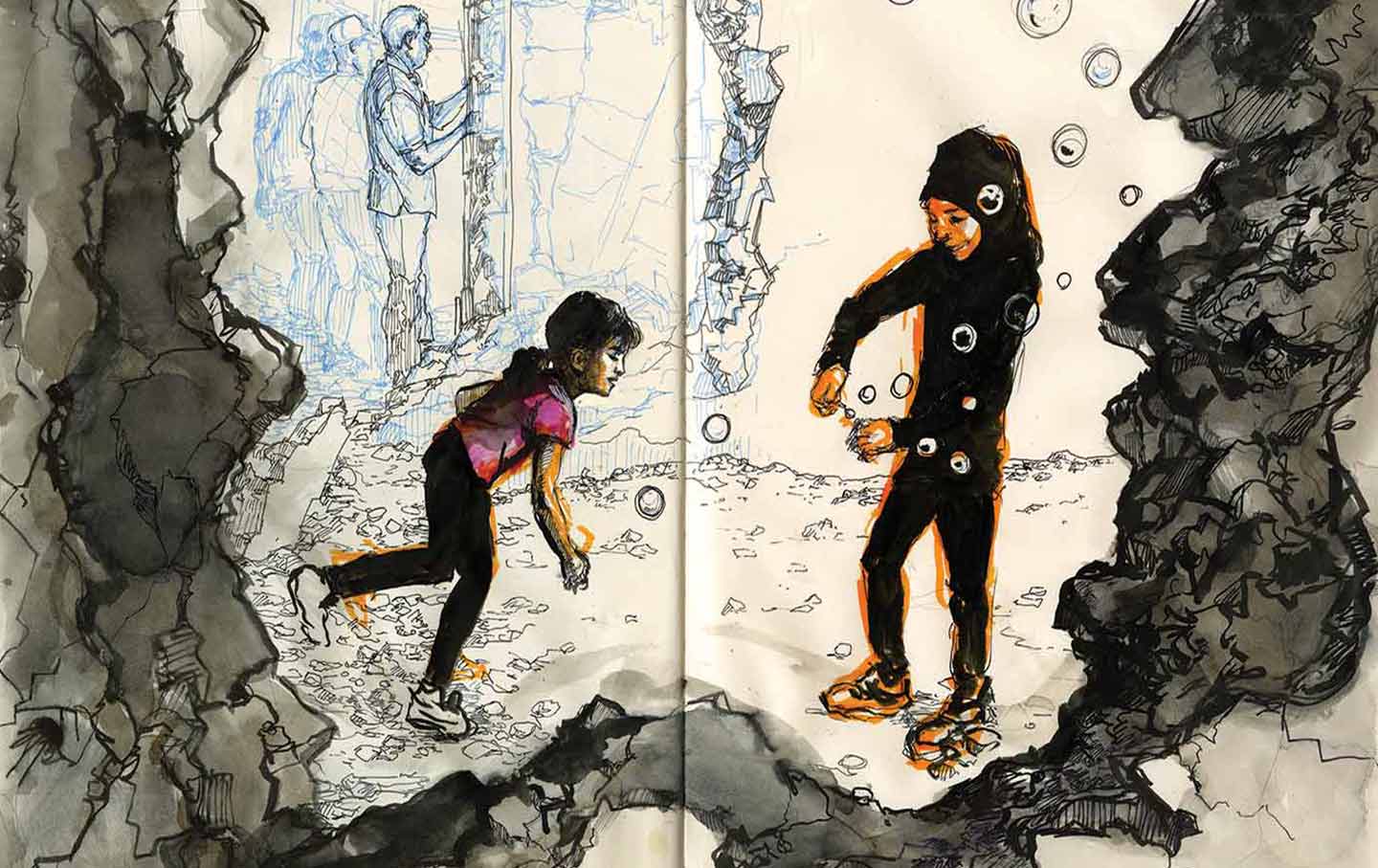

Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance

A new set of note cards by the artist and writer documents scenes of protest in the 21st century.

The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life” The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life”

In her new film, Jodie Foster transforms into a therapist-detective.