We don’t know what caused the spark. But we do know that a fire broke out on Thursday evening on the fourth floor of a five-story building in the heart of New York’s Chinatown. The flames flew upward, bursting out the windows of the top two floors. Firefighters rushed to the scene; a man trapped on the fifth floor was pulled from the inferno. Dense smoke poured from the 19th century structure, billowing out across lower Manhattan.

No one died in the fire. Several people were injured. And the next day, as many Chinese American families were preparing for Lunar New Year, the staff of the Museum of Chinese in America were confronting a grim reality. The city-owned building, still smoldering on Friday, had once been a public school; it now housed a senior center, a dance company, and several other educational and vocational organizations. It also held the entirety of MOCA’s collections and archives. That includes heirlooms and documents donated by hundreds of Chinese American families, historical artifacts, photographs, letters, artwork, store signs, and other everyday objects that might’ve once seemed mundane, but are now irreplaceable. The museum, and its collection, had just turned 40. (The building that houses MOCA’s galleries is several blocks away; it was untouched by the fire.)

News stories have stated that the archive holds around 85,000 objects; when I spoke to associate curator Andrew Rebatta on Monday, he said it may actually hold more than that. Conservators had not yet been able to enter the building, and the fate of the collection was unclear. But there was the possibility that these lovingly assembled materials had all been destroyed. “We always knew it was a space for community memory,” Rebatta told me. “But now we’re feeling it so much more.”

New York is a city known for its blockbuster museums, embossed on the landscape by industrialists: the Met, the Whitney, the Guggenheim. But it’s also home to many smaller museums, ones that grew out of communities that sorely needed them—including those founded in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, when activists started claiming physical space in which to tell their own stories. Offshoots of the civil rights movement, some of these institutions are still around today: the Museo del Barrio, founded by Puerto Rican and Nuyorican activists and artists; the Weeksville Heritage Center, which recovered the grounds of a forgotten free black community; and, of course, MOCA, created by a group of young Chinese American historians and organizers, who saw no evidence of themselves in the so-called official narrative.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

It feels petty to have to argue for why a place like MOCA is important—why this one community’s history should matter to everyone. The idea of “representation” has lost its teeth, used and abused by the same institutions and corporations that the founders of these small museums had wanted to circumvent. As the activist and scholar Angela Davis declared a few years ago, “Diversity is a corporate strategy…designed to ensure that the institution functions in the same way that it functioned before, except now that you now have some black faces and brown faces.”

That’s the hurdle facing institutions now: to turn tokenizing mandates into real engagement, across class, race, and gender. But we shouldn’t forget the work it took just to make “difference” understandable. When MOCA was founded in 1980, it was uncovering stories that the museums of record had barely bothered to touch. Its focus on the lives of New York’s Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans was, at the time, completely radical.

In an oral history from 2012, museum cofounder Charles Lai described the tear-it-down ideology that he and fellow cofounder John Kuo Wei Tchen espoused when they first started MOCA: “Those who think that they know best really don’t know. Those that have been oppressed for so long [can] become the oppressors. The [new] pedagogy is about trying to change that paradigm and change our understanding.” The goal was not necessarily to infiltrate the institutions that had ignored them, but to find a way to establish history by talking to the people who had lived it.

Lai and Tchen had met in the mid-1970s, through the New York Chinatown-based group Basement Workshop—an East Coast outpost of the Asian American movement that had started in California in the ’60s, when young members of different Asian diasporas decided to replace “Oriental” with a term that they thought better described their conditions. These activists felt that their parents and grandparents had suffered in silence, depoliticized and defanged by the traumas of internment, colonialism, war, and grinding, everyday racism. To claim Asian Americanness was overtly political, with inspiration from the Chicano, Native American, and black power movements: It meant rejecting white supremacy, opposing colonial agendas, and learning how to take up space.

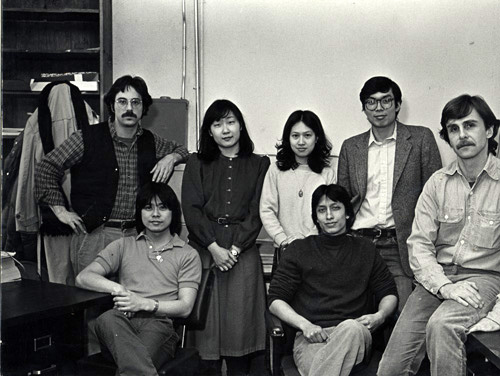

After parting ways with Basement Workshop, Tchen and Lai recruited a small group of others—including Jim Dao, Judith Luk, Yuet-fung Ho, Renqiu Yu, and photographers Bud Glick and Paul Calhoun—to join what was at first called the New York Chinatown History Project. At the time, some of Chinatown’s earliest residents were still around, though scarce; many of them were bachelors, their prospects for family curtailed by the United States’ Chinese Exclusion Act. Meanwhile, new immigrants from Hong Kong and Taiwan were arriving, beneficiaries of the 1965 Immigration Act that had removed racist quotas. Tchen and Lai saw that the neighborhood was changing before anyone had recorded it as it was. They began to scavenge the castoffs of declining Chinatown businesses and haul in trash from the street, open to its historical potential. They hung around a senior center—in the same building that caught fire last week—hoping to meet old-timers who would tell them their stories. Tchen, then a young historian, has said that he wasn’t able to find information any other way.

“I couldn’t understand this paradox—plentitude all around, yet yawning voids amidst the stewards of NYC and US history: collections and archives,” he writes in an essay published in the catalog for MOCA’s 2014–15 retrospective show. “It was as if this long-standing, omnipresent part of New York City had part of its past lobotomized.”

The group’s first exhibition, in 1980, focused on the lives of Chinese laundrymen, an older population that was on its way out. The show was called “Eight Pound Livelihood,” after the weight of an industrial clothes iron. They showed some parts of the exhibition at the senior center where they’d also scouted for subjects, opening it up to community feedback. “I could hear the seniors saying, ‘Oh, God, that’s my life,’” Lai remembered in the 2012 interview. The best part was watching people realize that their own experiences had left a mark. “Recognizing that we stand on their shoulders, and they felt like, ‘We actually have shoulders,’” said Lai. “That was huge.”

MOCA later moved into that same Mulberry Street building, showing exhibitions in four old classrooms and keeping its materials off-site; when the museum relocated to its current building in 2009, the classrooms were converted into storage for the collections and archive. Meanwhile, Chinatown is one of the last holdouts in a borough that was once a patchwork of vibrant immigrant neighborhoods—its vitality staked on a web of community organizations, outspoken local advocates, and real estate locked down in the 1960s and ’70s. Even so, predatory landlords and large-scale developments around Chinatown’s periphery are hastening gentrification. Many residents are vulnerable. The neighborhood remains a hub for new immigrants, and 28 percent of the people living there have limited English. Although Asian Americans are often painted as upwardly mobile and not in need of support, the numbers tell a different story: The poverty rate in Chinatown and the Lower East Side is 30 percent, more than double what it is in New York City as a whole.

MOCA, like many nonprofits, relies on a constellation of individual funders, foundations, public dollars, and intake from a yearly gala. The need to hustle for funding recently brought it up against the neighborhood it was founded to represent: When the city announced “give-backs” in exchange for Chinatown community members’ support of the construction of a new jail, some outlets reported that a local councilmember had used this to broker funding for a new performance space in MOCA’s main building. Since the museum would essentially be profiting from the jail construction, activists accused it of being complicit in gentrification and systems of incarceration. As New Yorker writer Hua Hsu—who cocurated a show at MOCA last year—wrote this week in a piece about the fire, “The controversy around the jails has called into question the purpose of MOCA itself—whether its survival is worth going against the will of some of its neighbors and constituencies; whether it can still abide by its hyper-local, dumpster-diving roots at a time of constant global exchange; and who such a museum is for in the first place.”

This news might seem to indicate a turn toward the kind of values that MOCA’s founders once sought to reject. But a crisis of this kind may have been near-unavoidable for an ambitious institution without, as Hsu puts it, “a preexisting base of Chinese-American donors.” The two other community-founded museums mentioned above also went through their own crises this past year: El Museo del Barrio was panned for honoring a wealthy donor who was discovered to have right-wing views, as well as for hiring a curator who is not Latinx; Weeksville—lacking wealthy, right-wing donors—was nearly shuttered, before an emergency fundraising campaign pulled it from the brink. Not to mention the protests against the city’s biggest museums, whose mission statements have been tainted by opioid wealth and teargas money.

If MOCA wants to stay close to the grassroots of Chinatown, it will need to confront the contradictions between the cross-class community it serves and its need for continuous funding. As moderate as MOCA’s mission may seem to us now, it has fiercely progressive origins, and its curators care deeply about the Chinese American story. There’s no reason MOCA can’t be pushed to keep reflecting the people that need it most. That’s part of why the fire is so potentially devastating: It happened right as the museum was poised to evolve.

I can’t pretend to be a neutral observer here. As I write this, my family’s history hangs on the museum’s walls, part of its current show, “Gathering.” The exhibition brings together artifacts and histories from Chinese diaspora organizations across North America, with the goal (as I saw it) to link these scattered narratives, using MOCA as a kind of catalytic hub. The institutions in the show range from deep-rooted museums to ad hoc heritage sites—including, in one case, a Chinese cemetery in a former Canadian mining town. That last one is my family’s: a burial ground cofounded by my great-great-grandfather, tended by my grandfather, and presented here by me.

At the show’s opening, I found myself talking ancestors with my fellow participants, who had traveled for the occasion from Mexicali, Mississippi, Maui. Many were part of my mother’s generation, people who came of age as the Asian American movement gained steam. Tchen—who left MOCA in 1986 and is now a historian at Rutgers University, Newark—gave a brief talk as well, drawing a through line between the present show and the museum at its founding, an alternative space with civil rights roots.

As I listened to Tchen speak and looked around the room, I had the rare sensation of being in the presence of elders: a sampling of those whose outlook had helped define what it means to be “Chinese American,” now a label to be embraced, subverted, expanded, or rejected entirely. If my own feelings about Chinese American-ness (or Canadian-ness) can tip into frustration—over “our” complacency, complicity with white supremacy, embrace of ethnonationalism, and so on—then these are feelings that have basis in self-recognition, a grounding that I am lucky enough to almost take for granted. Almost.

I want us to be able to keep troubling these ideas. For that, we require materials that can show us where we came from. MOCA’s collections are invaluable, with their mission to serve—as the museum’s curator, Herb Tam, wrote in the retrospective catalog—“as a counter-narrative to misrepresentations and racist stereotypes.” (A counter-narrative that coronavirus panic reminds us we still desperately need.) As Rebatta told me, the archive is crucial to the museum’s programming, inspiring many of their exhibitions. Before the fire, they’d already been planning a show about the ’90s collective Godzilla: Asian American Art Network, among several others. “The core, the bones, is this collection—it’s the source of everything,” Rebatta said.

As we spoke, the fate of those bones was still unclear. The museum’s president had already stated that the entire collection could be destroyed, but nothing had been confirmed yet. This week the city will begin removing MOCA’s items from the damaged building, transporting them to a place where conservators can begin triage. On Monday, the museum tweeted a zoomed-in photo showing stacks of storage boxes, visible through one of the windows: reason to hope that at least part of the archive could survive.

When I visited the site of the disaster on Monday evening, the man working at my favorite Cantonese sponge cake joint told me there had been another fire earlier that day; unbelievably, it happened just one block away. Back at the ruined community building, the city had erected a high plywood construction fence, then blocked off the intersection with metal police barriers. Signs were pasted to the fence in English and Chinese, redirecting patrons of the senior center. The top two floors of the building, where the fire had raged, looked forlorn and exposed: window frames gaping, roof blackened or gone. Standing on the corner, you could look up through the building’s fifth floor and see straight through to the sky.

But the neighborhood at dusk felt lively in spite of this scene, the scorched former school just one part of the street. Pedestrians flowed around the blocked-off intersection, stepping around the police barriers like they’d been doing it all their lives: teenagers gossiping, workers hurrying home with produce in red plastic bags. Awash in confetti from the New Year’s celebrations and glass shards from the building’s exploded windows, the pavement on Mulberry glittered under the streetlights. Occasionally, a passerby would stop to peek at the building through a hole in the fence: a glimpse at a Chinatown that could’ve seemed completely permanent, until one day a fire proved it wasn’t at all.