Mary Sully’s Astonishing Art Pictures American History Through Indigenous Eyes

A new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum reveals how deeply embedded a Native woman’s perspective on our culture might be.

When Jaune Quick-To-See Smith lit up the Whitney Museum’s galleries last year, and the New-York Historical Society followed with Kay WalkingStick’s painterly revisions of Hudson River School landscapes, it seemed as if Indigenous women’s art had finally made its mark on the contemporary scene. Both artists cast a cold eye on American history and American art while never descending into caricature, and although some of the art press celebrated their shows as something new, they weren’t really. The two artists have been admired for decades, if largely unknown to the wider museum-going public.

Over at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the revelatory exhibition “Mary Sully: Native Modern” (through January 12, 2025) suggests just how deeply embedded in American art a Native woman’s perspective on American culture might be. Until recently, Mary Sully (1896–1963) was all but unknown except as the sister of the ethnographer Ella Cara Deloria, the aunt of Vine Deloria Jr. (author of Custer Died for Your Sins), and the great-aunt of Philip Deloria (author of Indians in Unexpected Places, among other works). In 2006, Philip Deloria and his mother, Barbara, opened a tattered box of Sully’s art that had been passed down to them. What they found inside—more than 100 vertically arranged images, each done in colored pencil or graphite on paper—inspired Deloria to write his superb book, Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract. The works have now been restored, and 15 of the 25 that were purchased by the Met are on view in the museum’s American Wing.

She was not born Mary Sully; Susan Mabel Deloria was her birth name. Born on the Standing Rock Reservation, pathologically shy and reclusive in a family that was anything but, she adopted her mother’s maiden name—perhaps to link her art to that of her great-grandfather, the illustrious painter Thomas Sully, whose portrait of “Indian killer” Andrew Jackson is the source for the image on our $20 bill. The ironies don’t end there: Her grandfather Alfred Sully (1820–1879), a colonel in the US Army, would boast more than once about his 1863 massacre of Indians at Whitestone Hill. Alfred Sully left his Indian family and eventually married a daughter of the Confederacy.

An American story, although one that does not entirely explain how Mary Sully’s sense of irony and social justice kept such easy company with her witty, affectionate, and sly appreciations of figures in American popular culture.

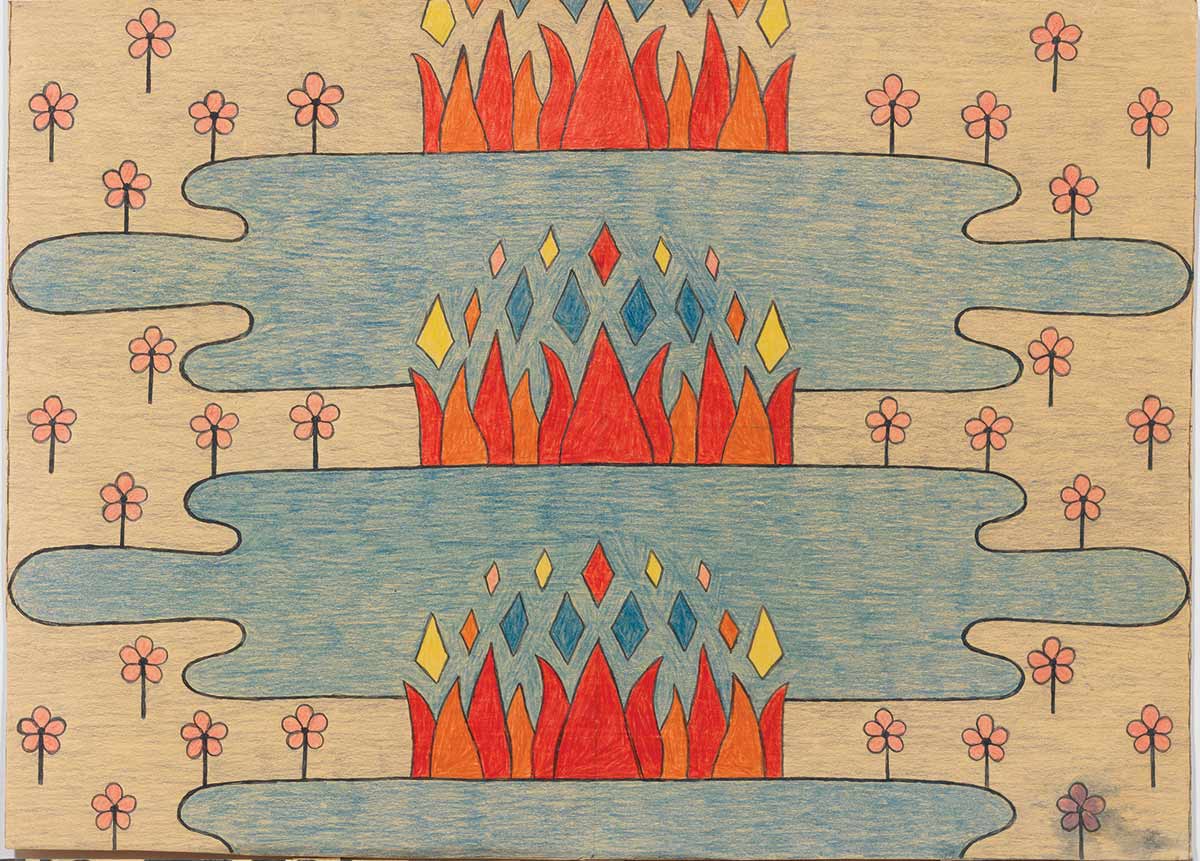

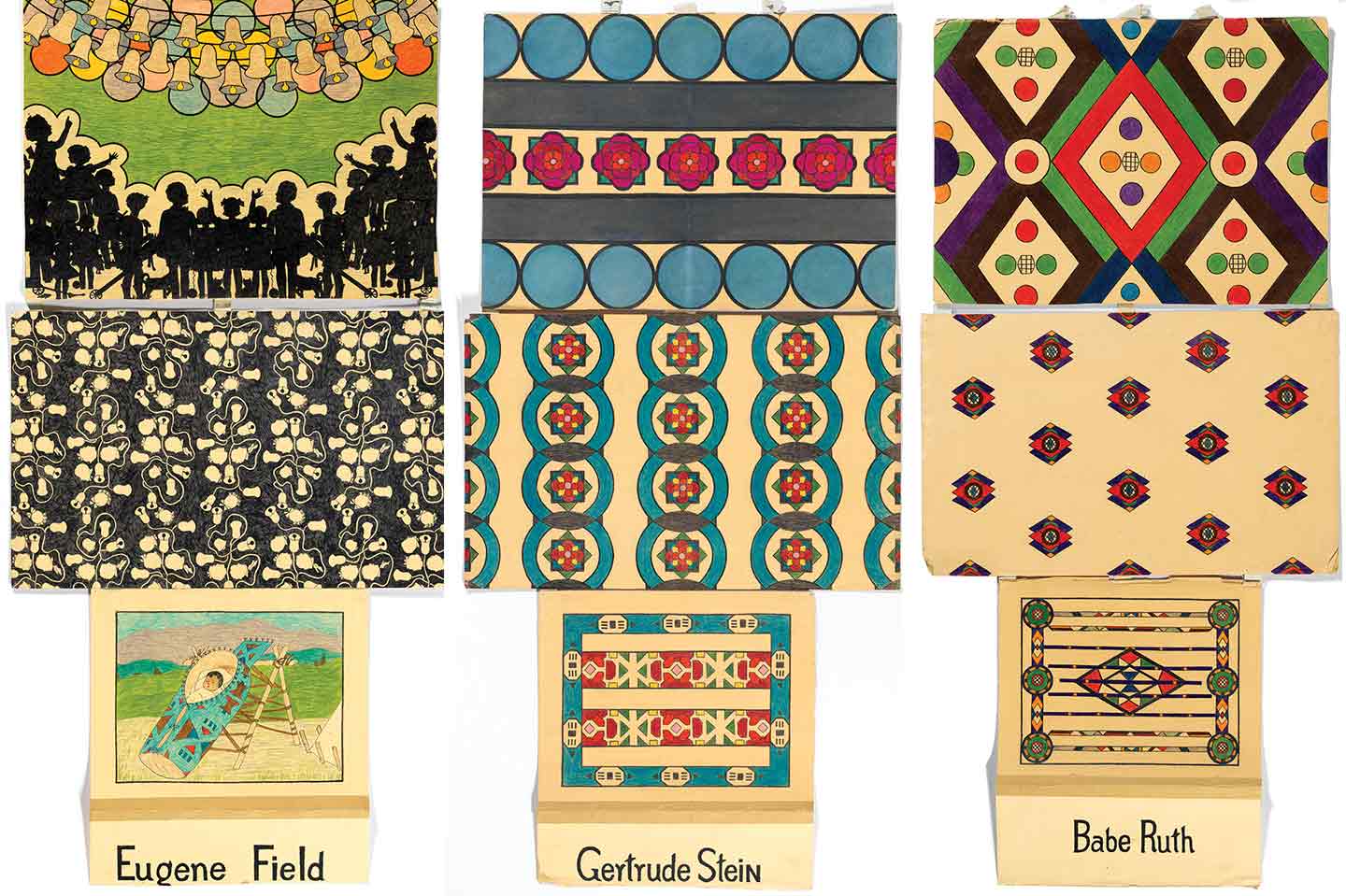

The Met has displayed Sully’s art in two adjoining galleries, one devoted to her “personality prints”—interpretations of Fred Astaire, Gertrude Stein, and Fiorello La Guardia among them—and the other to native themes and social issues. It’s a useful way to divide the work, though there is more than a little overlap between the two sets of images. If the personality prints are celebrations, they are so within a Native context. Gertrude Stein, for instance, begins with the inevitable rose repeated, as in her famous line. In the middle panel the rose undergoes a transformation as it is broken apart, and in the bottom panel it has been captured and abstracted into a design of the artist’s making.

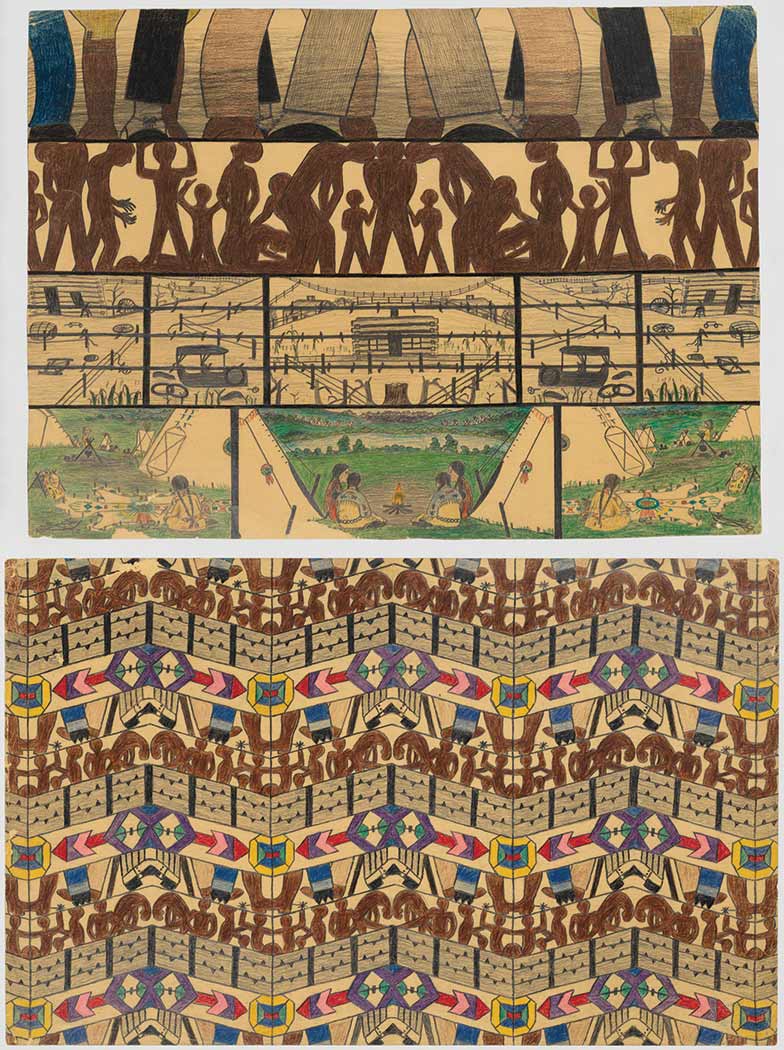

Fred Astaire displays a similar alchemy, beginning with the wonderfully antic but carefully balanced movement of dance steps in the top panel, passing through the transformations of the middle stage, and ending in the fractured encapsulation of movement in a Native pattern, again of the artist’s invention. Thus are these and other celebrities of their time turned around to face and be captured by something unfamiliar… at least to them. If these brilliant compositions are lighthearted, they nevertheless contain a serious undertow of Native wit.

The entrance to the adjoining gallery holds what may be a late summation of sorts: Three Stages of Indian History: Pre-Columbian Freedom, Reservation Fetters, the Bewildering Present. That title describes only the top panel, where, reading from the bottom up, a woman-centered pre-Columbian idyll gives way to the barbed wire of the reservation, which in turn culminates in the image of disembodied legs in pinstripes and spats over upraised brown arms.

But what of the bottom panels, with their arrows and diamonds? Here the wall label by the Met’s curator, Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha), suggests that the arrows “define past, present, and future generations as inextricable.” It’s a plausible and optimistic reading, and certainly one that corresponds with my understanding of the greatest influence on Mary Sully’s life, her sister Ella Cara Deloria, whose life and ethnographic work were inextricably tied to the artist’s.

Because Mary was so hampered by shyness (the layman’s term of the time), Ella assumed responsibility for her, and they were rarely apart. But the connection worked both ways. Doing fieldwork for Franz Boas on the Dakota language and culture, supervised by Ruth Benedict and later by Margaret Mead, Ella Deloria traveled widely. Mary was her driver on many of these trips, and her designs appear on a few of Ella’s monographs. The sisters were often in New York in the 1930s and ’40s, where the push and pull of two quite different cultures surely made an impression on them both.

Ella Deloria had struggles of her own. She died in 1971. Her major ethnographic work, The Dakota Way of Life, had to wait almost 50 years before being published in 2022. It is absorbing reading, but it shows a scholar obsessively concerned with and hampered by the tension between the demands of her fieldwork and her Nativeness. She persistently asks questions about ethnography as she rushes to document a vanishing culture—painstakingly noting what has been lost, forgotten, disparaged, or destroyed. You can see her struggling with the proper distance as she relates anecdotes and worries about losing the “zest and sparkle” that animate the Dakota language and its culture.

I am in no position to evaluate her ethnography, but I do see in Mary Sully’s art a resolution of the tensions that bedeviled Ella Deloria, where the zest and sparkle persist, and where, as the curator observes, generations are united and, improbably enough, nothing has been lost.

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?