How Was Sociology Invented?

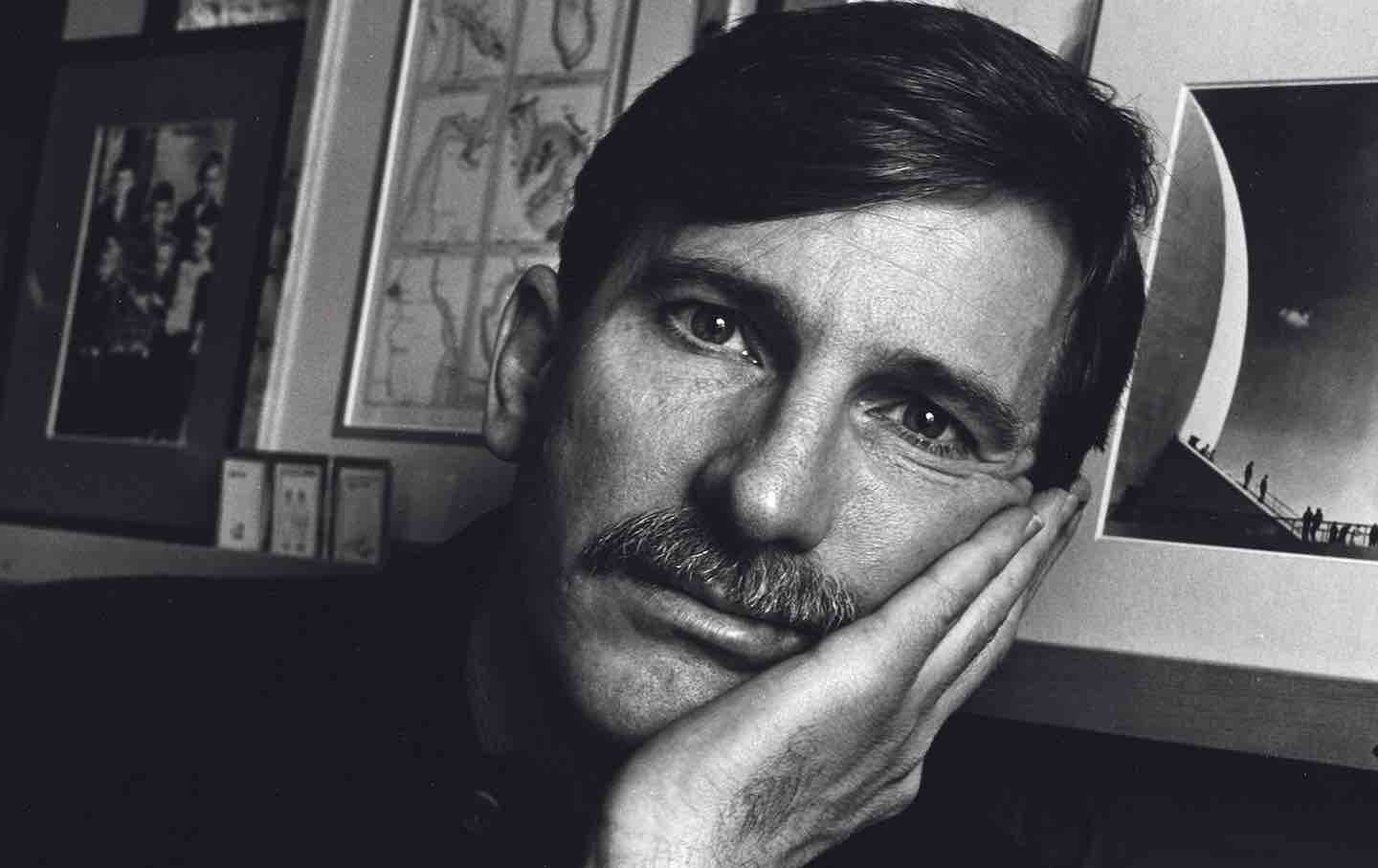

A conversation with Kwame Anthony Appiah about the religious origins of social theory and his recent book Captive Gods.

The philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah’s latest book, Captive Gods: Religion and the Rise of Social Science, is concerned with the origins of the social sciences. His main claim is that “it’s through religion that society becomes a disciplinary object.” What Appiah means by this is that the founders of the modern social sciences—notably Edward Burnett Tylor, Max Weber, Emile Durkheim, George Simmel—used religion as a framework through which they established sociology as a discipline. But what religious assumption, then, did their sociological analysis assume? And what significance does the religious origins of the social sciences have for contemporary social thought? The Nation spoke with Appiah about the anti-secular stance of right-wing movements, the invention of sociology, and his new book. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

—Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins: This book is principally concerned about the connection between religion and the rise of the social sciences. Perhaps its central thesis is the idea that “it’s through religion that society becomes a disciplinary object.” Can you elaborate on what you mean by this?

Kwame Anthony Appiah: What I mean is that “religion” was the way the classical sociologists like like Emil Durkheim, Georg Simmel, and Max Weber first managed to turn “society” into something you could actually study. Durkheim’s Elementary Forms defines religion as a system of beliefs and practices tied to sacred things, and what matters there is how those beliefs and rituals bind people together into a moral community—the church. For him, the believer isn’t wrong to think he depends on a higher power. That power does exist, but it’s society itself. For Weber, the religious creeds and customs of a people were the key to understanding the historical trajectory of a civilization. Simmel, meanwhile, thought of God as a kind of personification of society, a way of absolutizing our own rules. And then he borrowed from Friedrich Schleiermacher’s idea that religion is rooted in the feeling of absolute dependence on God and argued that this mirrors our dependence on the social order as it stretches across time and space. What we feel as religiosity, he suggested, is really an intimation of how society constitutes us and keeps us connected.

A critical point is that it’s in the same line of work that we see a new idea of “society” taking shape. Earlier thinkers tended to see it as just a collection of individuals under a contract, say, or as a static backdrop subject to divine or natural laws. By the late 19th century, though, the sense was that society had its own inner workings. It wasn’t reducible to individual psychology, or to the laws of the natural sciences. It had dynamics of its own—structures, sentiments, norms—that shaped people even as people shaped them.

You see this in Durkheim’s homo duplex: Each of us is both an individual and a bearer of collective life. Simmel stressed the constant interplay between social forms and the content that fills them. Weber takes up the concept of social action, and he’s fascinated by collective forms of self-transcendence. What religion gave them was a way into this discovery: By analyzing “religion” as a social phenomenon, they were really inventing “society” in the terms that we know it today.

DSJ: Does this argument assume a particular understanding of religion? I ask this question because my understanding is that there is no scholarly consensus on what religion actually is. The theologian Paul Tillich, for instance, defined religion as “ultimate concern” meaning that almost anything can be religious as long as it is the thing that someone cares about the most.

KAA: Right, one of the themes I keep coming back to in the book is just how elusive a definition of religion has always been. Tillich’s “ultimate concern” is one attempt, but there are dozens of others: ritual, belief in spirits, systems of symbols, social glue, a sense of absolute dependence, and so on. None of them really carries the day. In fact, not everyone has thought “religion” was even an intelligible category. Wilfred Cantwell Smith, in the ’60s, argued that it wasn’t—that the term conflated too many different things to be a valid object of inquiry, and that we’d be better off speaking of “faith” and “cumulative traditions.” There were strong arguments there: Critics noted how much the concept seemed to owe to a Protestantized model of belief and how awkwardly that fit what you found in much of the rest of the world. It was fair to ask: Does “religion” exist?

What’s striking is that even the skeptics couldn’t quite do without it. They kept lapsing in their vows, going back to using the word. There are a lot of semantic stakeholders here. It’s not that there’s some single right answer. It’s that the very effort to treat “religion” as a discrete object of study was what helped conjure into being “society” as a parallel object. The thesis doesn’t depend on a dogmatic definition so much as on the historical fact that the attempt to give contours to religion was a critical part of the intellectual work that made “society” visible.

DSJ: What is interesting about the key figures discussed in your book—Edward Burnett Tylor, Durkheim, Simmel, and Weber—is how you connect their personal biographies to your argument about the rise of the social sciences. In other words, all four are undergoing a process of secularization, even as they acknowledge the integral role that religion plays in the advent of modern secular societies, and in their family histories. You yourself acknowledge something similar about your own background when talking about growing up around Christian, Islamic, Jewish influences and how they shaped you. All of which leads me to wonder if the rise of the social sciences really is about the rise of a new class of Western educated academics who are grappling with their own personal experience of moving away from traditional religion.

KAA: It’s natural to think that Tylor’s break from Quakerism and Durkheim’s break from his rabbinical lineage gave each of them some secular skin in the game. But I should also note that secularity itself was a civic ideal introduced and advanced by religious people. In particular, by religious minorities, as both Tylor and Durkheim were, because if you’re part of a non-state religion, you’ll be drawn to the idea of a separation of church and state.

Now, with Simmel, you’re looking at someone who hadn’t grown up with much religious observance at all. Which makes it all the more impressive that he was so sensitive to the affective charge of religion, and so quick to reach for the language of tone and color to capture experiences that fascinated him precisely because they felt exotic, a little strange. And Weber, of course, described himself as “religiously unmusical.” Even in his teenage letters, you see him writing about piety as though peering in from the outside. He could theorize brilliantly about the social power of religion, and he stressed that he wasn’t anti-religious, but he suspected he had a tin ear for the sacred and the spiritual.

For all of them, I agree, the retreat of institutional religion was not just a social fact they observed but also a standpoint from which they thought. It’s just that they weren’t congratulating themselves on their skepticism. On the contrary: that distance helped them explore how religion’s force still lingered in modern life, under other guises. Secularization was something they saw—and something they saw through.

DSJ: With the rise of the social sciences in the late 19th century there was a real concern, especially in Germany, with the attempt to model the human sciences on methods of the natural sciences, as you show in your chapter on Simmel. In other words, there was the fear that the humanities would be delegitimated by an over-fixation on the regularities of the natural sciences as it alone was viewed as a true science. In this regard your book shows the vital role that religion played in early sociology, and in particular for resisting this tendency. Might the failure to value this distinction be a way of explaining why the humanities are in such a state of crisis today, especially given how little they are funded in comparison to STEM fields?

KAA: I do find it fascinating to revisit those late-19th-century debates. Ernst Mach, the Austrian physicist, complained that humanists and scientists were behaving like the Montagues and the Capulets, and he hoped for a Romeo and Juliet to unite them—ideally, he added, without the tragic ending. Humanists, of course, worried about whose terms the marriage would be on.

The social theorists in my book were alert to the danger: that the richness of lived experience would get flattened into a set of mechanical laws. Religion, as I argue, was a counterweight here. In grappling with ritual, feeling, community, and dogma, these thinkers insisted that cultural inquiry needed its own categories and methods.

I’ve sometimes found the distinction that Wilhelm Windelband drew in the 1890s between the “idiographic” and the “nomothetic” to be useful. The idea is that the humanities tend to focus on the singular—the French Revolution in all its contingencies, say—while the sciences pursue the general rule, the law that holds no matter the time or place. To put it differently: The humanities can ask what made this event, this person, this text distinctive. The sciences seek to identify universal laws of nature. Of course, the line isn’t sharp; these are tendencies, not watertight compartments. Both endeavors are indispensable, but they’re not the same. And sociology ended up carving out a kind of third space between them.

So one debate was about what you were trying to understand. Another was about what counted as understanding it. Simmel and Weber made much of Verstehen—a sort of interpretive, experiential grasp, as opposed to a more mechanistic explanation, Erklären. Windelband wanted to replace that distinction with his idiographic/nomothetic distinction, though in practice his scheme mostly piled on rather than displaced what came before. And then there’s the matter of values. Not just the values scholars bring to the table, but the values they study. At one point, Simmel asks what happens if we take religion not as a bundle of empirical claims but as a state of being. It’s problematic, sure, but it opened up a way of treating religion as a framework for interpreting and judging empirical claims without making such claims itself.

That’s not so far from what a lot of qualitative and interpretive scholarship still does. Which is why today, when the humanities are starved of funds and legitimacy, part of the trouble is a failure to grasp these old distinctions. Understanding society, history, and culture needs tools other than those you’d find in a laboratory. Now, one sign of the strange times we’re living in is that we now have to worry about those laboratories, too, because politicized policymakers have taken them hostage in their battles.

DSJ: Durkheim famously equated religion with society. Of course, in Third Republic France that wasn’t such a leap to make as ethical teaching in the name of society seems little more than a counterpart to being in a predominately Catholic culture. Do you think, however, that something like Durkheim’s notion of a shared collective consciousness can apply to a country as big and politically divided as the US?

KAA: You might think that Durkheim had more personal reasons for thinking this way. He grew up in an orthodox rabbinic community, so he knew what it felt like to inhabit a total moral world. As he’s writing, Catholicism in France was losing its grip under laïcité and anticlerical laws, but he could see that republican ideals were taking on a sacred glow of their own.

Still, his ideas weren’t just a French reflex. He’d spent time in Germany, where the leading social theorists had come of age in a famously fractured political landscape. And when Durkheim talked about “collective consciousness” in the 1890s, he didn’t mean some mystical group mind. He meant the shared moral world that small, tight-knit communities tend to generate. He thought you saw it most strongly the farther back you went in history, and he believed that as societies modernized, religions got less all-encompassing and more open. By the 1900s, he’d retired the psychological talk of “consciousness” and started speaking instead about the “collective representations” through which societies sketch out their moral blueprints.

He wasn’t really chasing the idea of a grand national spirit. He was asking a more basic question: How does any community, large or small, manage to reproduce its moral order? And though he never made it to America, Weber did, just as he was drafting parts of The Protestant Ethic. What Weber saw here—the dizzying variety and vitality of sects, of small denominations—only reinforced his belief that theology could be an engine for an entire civilization. And if you follow Durkheim’s later language, those “collective representations”—the rituals, symbols, and practices that carry a society’s self-understanding—are remarkably potent in America, even if they’re as much sites of contestation as of consensus.

DSJ: All of the main figures you discussed were in some sense trying to articulate the ties that bind modern societies together despite the gradual fading away of traditional religion. Fast forward to our current moment, and sociologists talk of an unprecedented loneliness epidemic that marks modern Western societies. Is secularism to blame?

KAA: Experts debate whether there really is such an epidemic. There’s certainly a lot of talk about it, and it’s true that nonreligious people often report being less happy on surveys. Whether or not people are feeling lonelier, they feel they feel lonelier. Part of this might come from the way contemporary cultures have heightened our reflexivity. We’re constantly encouraged to monitor our own emotional states, to measure ourselves against others, to narrate our experience in therapeutic terms.

But I want to complicate the picture. If you go back to, say, the German history of Pietism, which gets started in the late 17th century, you see that the underlying issue isn’t new. When Pietists exalted heartfelt devotion over formal ritual, they obviously weren’t rebelling against secularity. They were rebelling against what felt like bloodless institutions and practices. Pietism was an effort to find intimacy, immediacy, inwardness, deep interpersonal communion—hence those little collegia pietatis. Versions of this craving have been with us for centuries. Even in a thoroughly religious world, people could experience a sense of spiritual emptiness and the desire to feel full again. That’s why Weber said that religious experience gets hollowed out as soon it gets systematized and institutionalized. And it was Weber, too, who stressed that Calvinism’s doctrine of predestination—the idea that no matter what you did, your fate was fixed—could leave you with a feeling of “tremendous inner loneliness.” In other words, the discontents we now ascribe to secular existence were once ascribed to certain kinds of religious existence.

What’s more recent is the idea that we might have nonreligious forms of religion. When Durkheim talked about the “religion of humanity,” he had something like this in mind. For Simmel, the religious impulse was like a hermit crab, which could readily inhabit very different shells. He decided that the “problem of religion” would be solved if people lead religious lives—not lives “lived with religion” but lives that were, in their essence, religious. He’s using the adjectival form. That’s the move the German sociologist Ulrich Beck makes too. He tells us to distinguish between “religion” and “religious.” The noun sets up an either/or—are you in or are you out? The adjective works differently; it opens the door to a both/and. You can be “religious” in your orientation to ultimate questions without belonging to any particular institution. Here the point is that climate activism, human rights activism, or even the “wellness” movement involves forms and feelings we associate with religion. From that angle, the story isn’t just about secularism eroding our ties. It’s about people constantly reinventing forms of shared meaning, even if they don’t look like the churches of the past.

DSJ: Do you see a connection here with the success of rightwing authoritarian movements which are almost all resoundingly anti-secular?

KAA: Let me start by saying that the theorists I write about would probably frame the story differently. They’d ask whether these authoritarian movements really are simply reactions against secularism, against a supposed loss or loosening of faith. Someone like Viktor Orbán doesn’t present himself as a regular churchgoer or a pious congregant. Instead, he’s a defender of “civilizational Christianity.” And when he talks about his opponents, he doesn’t describe them as godless, or slack in their convictions. He calls them pious, even fanatical, adherents of a false creed. He says that European liberals in Brussels are missionaries on behalf of “the ideology of universal salvation and peace” and that they brook no dissent because their message to humanity can be “valid and true only if it is true without exception.” That is precisely the language of one universalizing religion attacking another.

Culture wars have long been waged in that key. The very term Kulturkampf originally referred to Bismarck’s battle against the Catholic Church in the 1870s. In contemporary America, you hear the same anathematizing register, when people on the right rail against the “woke mind virus,” describe the Democratic Party as “demonic,” demand a “360-degree holy war,” or charge that what liberals support is “Satanic.” And I’m putting aside those lurid QAnon theories about literal Satan worship. The point is, these aren’t attacks on disbelief. You don’t wage a holy war against atheism. You wage it against a rival creed—against people who, in your view, bow to all the wrong gods.

DSJ: Given all this, in what sense might your book be considered a kind of recovery project?

KAA: My social theorists were, to circle back, skeptical about any simple version of the secularity thesis, the idea that modernity simply means religion fading away. That’s a story people still reach for, but it wasn’t theirs. Durkheim, Simmel, Weber—what fascinated them was how “religion” and “society” became intelligible only in relation to one another, and my book is about how that interplay gave birth to the social sciences.

Today we often reduce religion to survey data about declining church membership. But for these earlier thinkers, religion was at the heart of understanding society itself. Religion, in their sense, was a definition-defying tangle of beliefs, practices, and feelings whose edges were always blurry. And what mattered was not simply what people thought or did or felt but how they lived together.

That idea hasn’t gone away. Various cognitive scientists now argue that large-scale societies required belief in supernatural enforcers of moral norms. Interpretive sociologists explore forms of religiosity that don’t recognize themselves as such. Weber, memorably, imagined a modern world prowled by a pantheon of rival gods, each with its own values, each fighting for followers. Which sounds a lot like the world we inhabit.

So if Captive Gods is a recovery project, it’s about bringing back the recognition that every society generates and sustains itself through transcendental meanings. And it’s about the modesty this recognition should inspire: the willingness to make room for practices and beliefs we don’t ourselves see the point of, and to interrogate our own dogmas as much as anyone else’s. Or, as a fellow once said: “Sit down, be humble.”