Lurking in the Shadows of the Deep State

A conversation with the journalist Kerry Howley about her reporting on whistleblowers, drone warfare, and an upcoming film adaptation of her writing on NSA leaker Reality Winner.

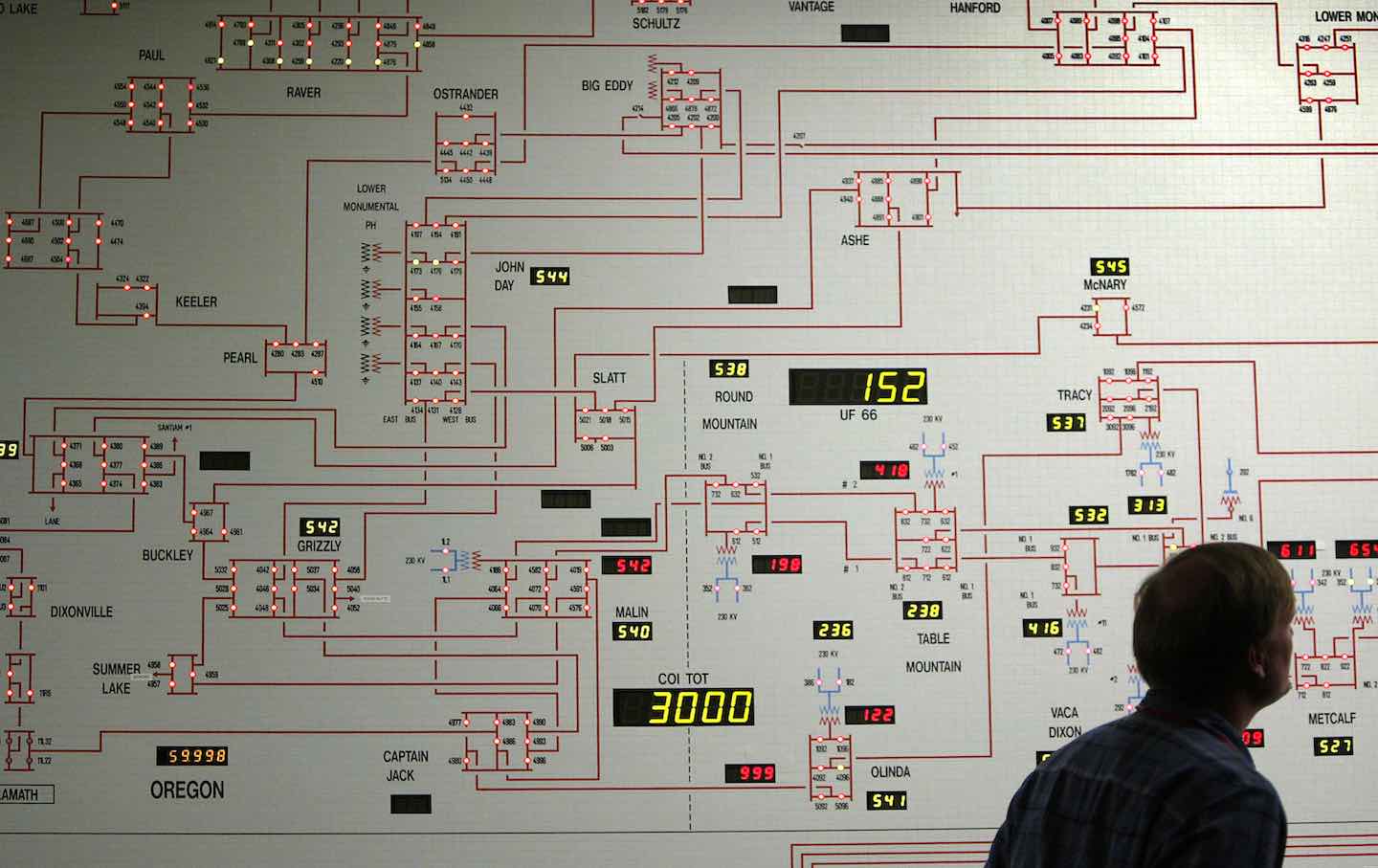

NSA headquarters in Washington, D.C., 2006.

(Photo by Brooks Kraft LLC / Corbis via Getty Images)In the past few years, the story of Reality Winner—the former intelligence specialist who was prosecuted for leaking a classified report on a Russian cyberattack—has served as fodder for a play (Is This a Room), a documentary, and an HBO film (Reality). The play and film drew a forensic chalk circle around Winner’s interrogation by FBI agents; they conveyed the tense atmosphere in which she divulged information that led to her eventual arrest and subsequent charges under the Espionage Act, but viewers learned little about Winner’s background—who she was before enlisting in the Air Force, training as a translator, and then becoming a contractor and finally a leaker.

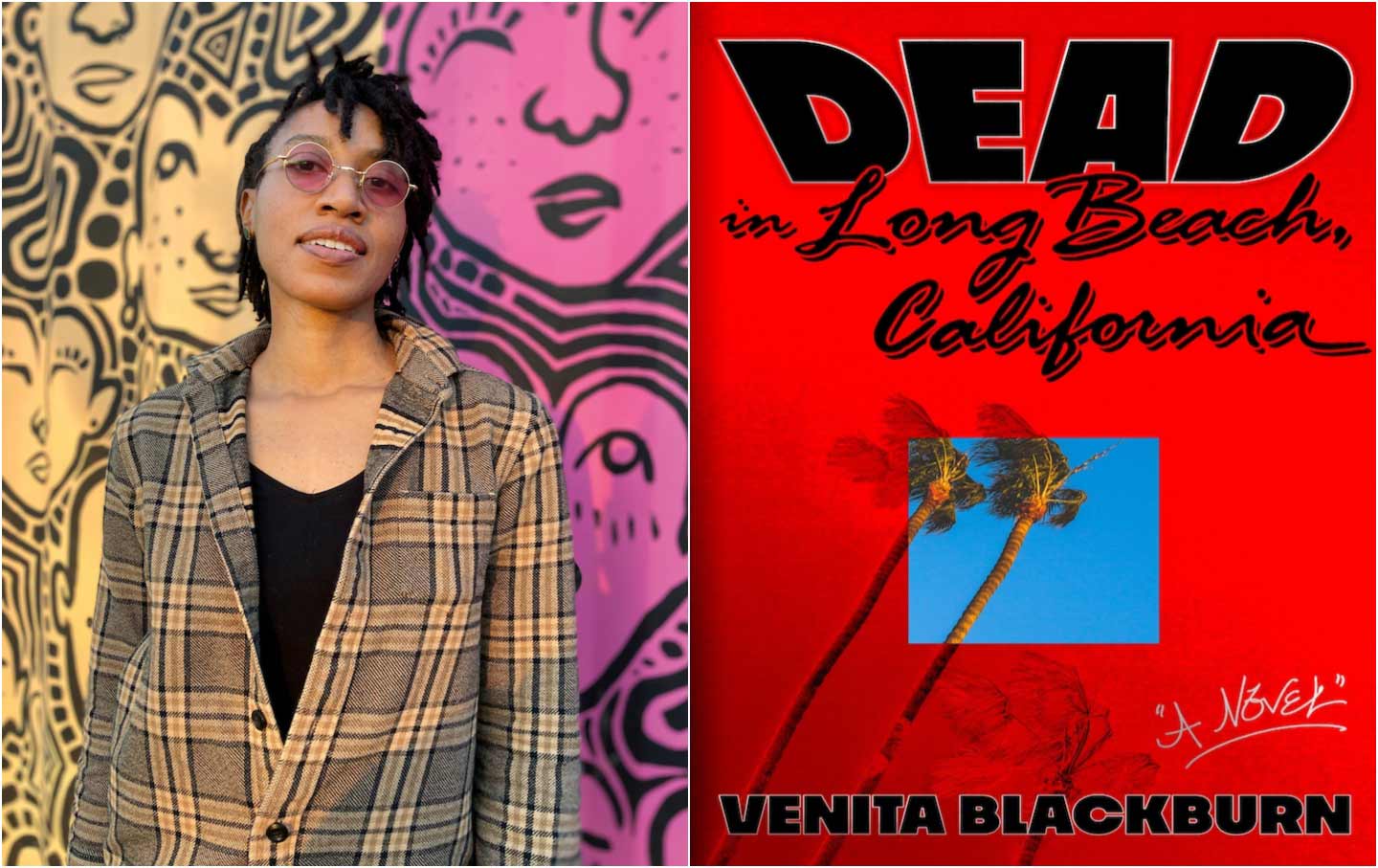

A recent book, Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs: A Journey Through the Deep State, by Kerry Howley, a writer for New York magazine, provides a much fuller picture of Winner. We learn that she once asked her high school boyfriend to read a specific number of books each week and that she’s an accomplished painter whose “most frequent subjects were herself, Nelson Mandela, and Jesus.” She also seems to have a great sense of humor. “I’m often asked whether Reality is a good or bad person, whether she did a good or bad thing, and I’m not being coy when I say I don’t even know how to begin to answer this question,” Howley told me. “Once, in court, when she was tired of being drawn by an incompetent courtroom sketch artist, Reality met his gaze, picked up a pencil, and began to draw him. That’s the moment worth writing into…. These moments are the text, the thing worth essaying, and they happen to relate in a bizarre way to a large and largely invisible apparatus that rules over all of us.”

Howley’s book grew out of a profile of Winner, but it is not exclusively concerned with the cryptolinguist, whom Howley has called “a never-ending, frequently exhausting source of information on the world, its problems, and our collective obligation to pay attention.” Bottoms Up kaleidoscopes the story of Reality Winner with those of other people who leaked state secrets, including Julian Assange, Edward Snowden, and John Kiriakou, a former CIA agent who confirmed that the organization waterboarded detainees.

As part of her official duties, Winner worked with drones and was assigned to eavesdrop on conversations; she also bristled against the “intimate violence” of her job. Howley’s book itself moves drone-like over various subjects: In the space of just a few pages, she writes about cell phones (“wave-spitting little beacons”); Daniel Hale, who leaked the secret documents that were basis for The Intercept’s eight-part series “The Drone Papers”; a Jordanian pilot tortured by ISIS militants; and Winner’s trip to SeaWorld as a child. Howley told me that her experience of writing the book was “agoraphobic, not claustrophobic.”

Later this year, Howley’s writing on Winner will become the basis of another film: Winner, starring Emilia Clarke of Game of Thrones fame. The Nation spoke with Howley about Bottoms Up, the upcoming biopic of “Re” (as Reality’s family refers to her), and how her story opens up an “exploration of an anxiety particular to our time.”

—Rhoda Feng

Rhoda Feng: What inspired you to write about Reality Winner, and what drew you to the topic of government whistleblowers writ large? Also, is “whistleblower” really the right word to describe Reality?

Kerry Howley: I was assigned a profile of Reality in 2017, before anyone knew anything about her beyond the outlandishness of her name. The book, though, is born of a different impulse. It’s a work that grew out of an anxiety many of us live without naming—the sense that we are leaving pieces of ourselves all over the ether, and the possibility that those pieces might be reassembled to create a self we do not recognize. You play a character in your group chat; that exchange is alienable from you, and it is possible to build an image of you that is at once factual and deeply wrong. I don’t mean this in any sort of normative or nostalgic sense; it’s not that life before was better, our identities somehow more authentic. It’s simply a change we are experiencing, and the book is an attempt to defamiliarize and concretize the change.

In the service of restoring reality to sensory experience, I drove people bonkers asking what things look and feel like: “Tell me about the threads of glass undersea along which the electrons travel. Tell me how hot the machines are, tell me about the water used to cool them, the dogs used to guard them.” I asked a whistleblower who’d told us much of what we know about the drone war to describe the drone itself. He’d never seen one in person. I wanted to make the world feel as real as it is. Whether I succeeded is a different question, but that’s the energy underneath the page.

RF: You also have a forthcoming film about Reality that you’ve described as a “comic coming-of-age story.” Did you come up with the idea for the film while you were drafting Bottoms Up?

KH: I was approached by a producer to write that script and remain amazed that anything came of it. Our idea was always a fast-paced, comedic work—the antithesis of the dark (often literally dark) whistleblower movie in the halls of the NSA. The flat, ominous, self-serious feel of so much work about leakers and government agencies is not something that interests or feels true to me. You simply cannot depict the reality of our government if you aren’t willing to see the darkly comic incompetence at the center of things.

This isn’t in the film, but to this point: The torture program was something I was only kind of atmospherically aware of when it was first made public. I did not therefore know that the guys who came up with the program were just two psychologists willing to sell themselves as experts—men with no language skills, no expertise in interrogation, no relevant knowledge at all. One had studied “family therapy” in grad school, and the other had studied the effects of diet and exercise on blood pressure. What an absolute amateur shit show the torture program was… just the darkest comedy of errors. I don’t think you could tell that story with the flat self-seriousness of competent men in dark suits giving one another orders. That’s not how it happened at all.

RF: Do you hope that your film accomplishes something different than your book?

KH: I hadn’t thought of them in relation to one another before. The book is an essay, an exploration of an anxiety particular to our time. It’s one attempt to understand the relationship between being online and having an identity, and it proceeds by a kind of associational logic. The film, a collaboration between myself and the filmmakers, is pure narrative: It follows a single person’s journey from incorrigible Texas kid to the prisoner drawing pictures of her sketch artist. It’s clean in a way the book resists. Both, I hope, hover in an unstable way between tragedy and comedy.

RF: I haven’t seen the film yet but am curious to know if it dramatizes the relationship between Reality and her sister, which I found one of the most fascinating parts of your book. At one point, you write: “Reality was intellectual but she had not been raised in an intellectually sophisticated household.” The picture of her that emerges is one of an autodidact—someone with no clear allegiance to this or that “ism.” You liken her to Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning, and Daniel Hale and write that “an intellectual orphan comes to knowledge absent the social pressure to conform to a particular set of ideas.” Yet other parts of the book complicate the idea that Reality was not reared in an “intellectually sophisticated household.” I think the ways that characters squirm in and out of their original outlines proves your larger point that people aren’t just one thing.

KH: From the moment you try to create a character out of a person, you start to revise to accommodate someone bigger and messier. Anything you make will be shattered—if it’s stable, you’ve failed. I should add that the film is a work of fiction, heightened for humor and pace.

RF: You note that “through Manning, [Assange] created a new kind of leak not targeting a specific wrong but covering many wrongs, an increase in scope that mirrored the increase in surveillance itself. If the government would collect data massively and indiscriminately, data would be leaked massively and indiscriminately.” How does Reality fit into this broader trend?

KH: Early on in the book, a woman notes that Reality’s leak was so thoughtful: a single document, neatly delivered. It was not indiscriminate but pointed—an argument, a response, a challenge, perhaps. It used to be that your typical leaker was a fiftysomething bureaucrat who knew the system well and had some problem with it. Reality was part of something new: people under 30, exposed to the masses of information kept secret, largely for no good reason, who had grown up listening not to distant anchormen but to niche activist-journalists one might well feel a sense of companionship for. One might feel that such a journalist was on your side—would receive, with gratitude and sufficient context, your sacrifice.

RF: You have one line in the book about how “the internet is vision externalized.” Can you say more about this? It makes me think of the philosopher Justin E.H. Smith’s claim, in The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is, that the Internet is a kind of digital or cognitive prosthesis.

KH: At this point, the Internet, the “cognitive prosthesis,” is inseparable from surveillance. It’s a part of us, and that part of us is consistently watched. It’s very hard to think about a part of yourself, and it’s hard to think about anything in which you are enmeshed. One thing we can do is try to imagine the hardware. It’s a series of tubes, and we should spend more time visualizing them.

RF: Drones are another kind of technology that externalizes vision. You write that, contra the popular notion that drones create a kind of alienating distance between operators and their targets, the experience of operating a drone is “of deep, half-imagined, crazy-making intimacy…. Drone operators watch families retrieve limbs from exploded bodies.” It’s hard to read a sentence like that and not think that drone operators must suffer from PTSD as often as combat troops on the ground do.

KH: I think that’s right, and of course it’s then hard to obtain help; what you’ve seen is classified, and talking about it with someone who isn’t cleared is a federal offense. Most people can compartmentalize, but that’s a kind of damage, too.

RF: The five-page document that Reality leaked concerned a cyberattack by Russian intelligence on a US software company that provided election support to several states. As we approach an election year, more outlets and organizations have been demanding accountability for election subversion and intimidation. One in three election officials surveyed in 2022 knew someone who had left their job running elections because they didn’t feel safe, and one in five election officials plan to leave their jobs before 2024. In addition to the potential for cyberattacks that could stop people from voting and call into question the election results, we now also have to contend with the threat of AI in election-related communications. Do you have concerns about the security of voter data? And do you want to comment on any of the above?

KH: I think one can only feel anxious about all the unknowing involved in what you’ve articulated. I also think it’s interesting that the rioters responsible for January 6—people who tend to be very concerned about government surveillance—were mostly caught because they filmed themselves committing serious crimes… posting big pointing-finger emojis next to the words “This is me” while participating in an insurrection, things like that. Whatever happens will involve a kind of complexity, an interplay between the surveillants and the surveilled, that none of us can presently predict.

RF: What role do you think the media plays in shaping public perceptions of leakers like Reality?

KH: There’s a heavy presumption in mainstream media that leakers are traitors. I don’t share this intuition. Still, leakers unsettle the people to whom they leak. Even when an audience is glad to have the information, they seem to want to keep a distance from the messenger. I think Reality’s story enables a kind of thinking through a system that is otherwise, in its vastness, almost impossible to think about.

There is a certain kind of person who has devoted themselves to thinking about the things the rest of us spend so much energy not thinking about. I admire so many of these people—I’m thinking of journalists like Radley Balko, Liliana Segura, and Spencer Ackerman, and people who work in criminal justice, such as Emily Galvin-Almanza, who is, quite relevantly, the daughter of the poet (Josie Graham) who has expressed most clearly the patterns of mind produced by the digital world. I’m thinking of the kind of people who won’t stop talking about the conditions under which pigs are forced to live in Iowa.

Reality Winner is like this, and so, I think, is the Intercept journalist whose carelessness helped put her so swiftly in jail. I don’t know that you can ever “influence the discourse.” I think of these people as lights in a persistent darkness—and, to be clear, I do not count myself among them. I just wrote a feature about a luxury grocery store.… I can exist quite happily in the darkness.

RF: Your book ends with Reality’s parents visiting her in prison. Since your book came out, Reality has been released and has moved back in with her mother, though she wears an ankle monitor and can’t talk about her time in the Air Force. Do you know if she’s had a chance to read your book?

KH: Reality’s mother has been extraordinarily kind about the book, and in a way I think she, not Reality, is its beating heart. The essay is dedicated to the “Mothers of Reckless Children”; I wrote the prologue after finding out, while alone at a writing residency in the disturbingly open space of Marfa, that I was pregnant. I thought a lot about how we tell our kids to do what they believe is the right thing, and how devastating it can be when they follow through. Do we really mean what we say? Perhaps living morally in this society would involve a kind of lawlessness and asceticism no one wants for her own child.

Reality keeps a distance from the works about her, which I think is wise. She is a person who is sophisticated about the relationship between art and life, between one’s interiority and public narrative. I think she knows no static work can ever capture the full complexity of her identity, which is ever-evolving and, at some deep level, unknowable even to her. All I can do is try to do better, to introduce more ambiguity and enable more negative capability than a public identity previously allowed for. I hope I have done so.

Thank you for reading The Nation

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply-reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Throughout this critical election year and a time of media austerity and renewed campus activism and rising labor organizing, independent journalism that gets to the heart of the matter is more critical than ever before. Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to properly investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories into the hands of readers.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.