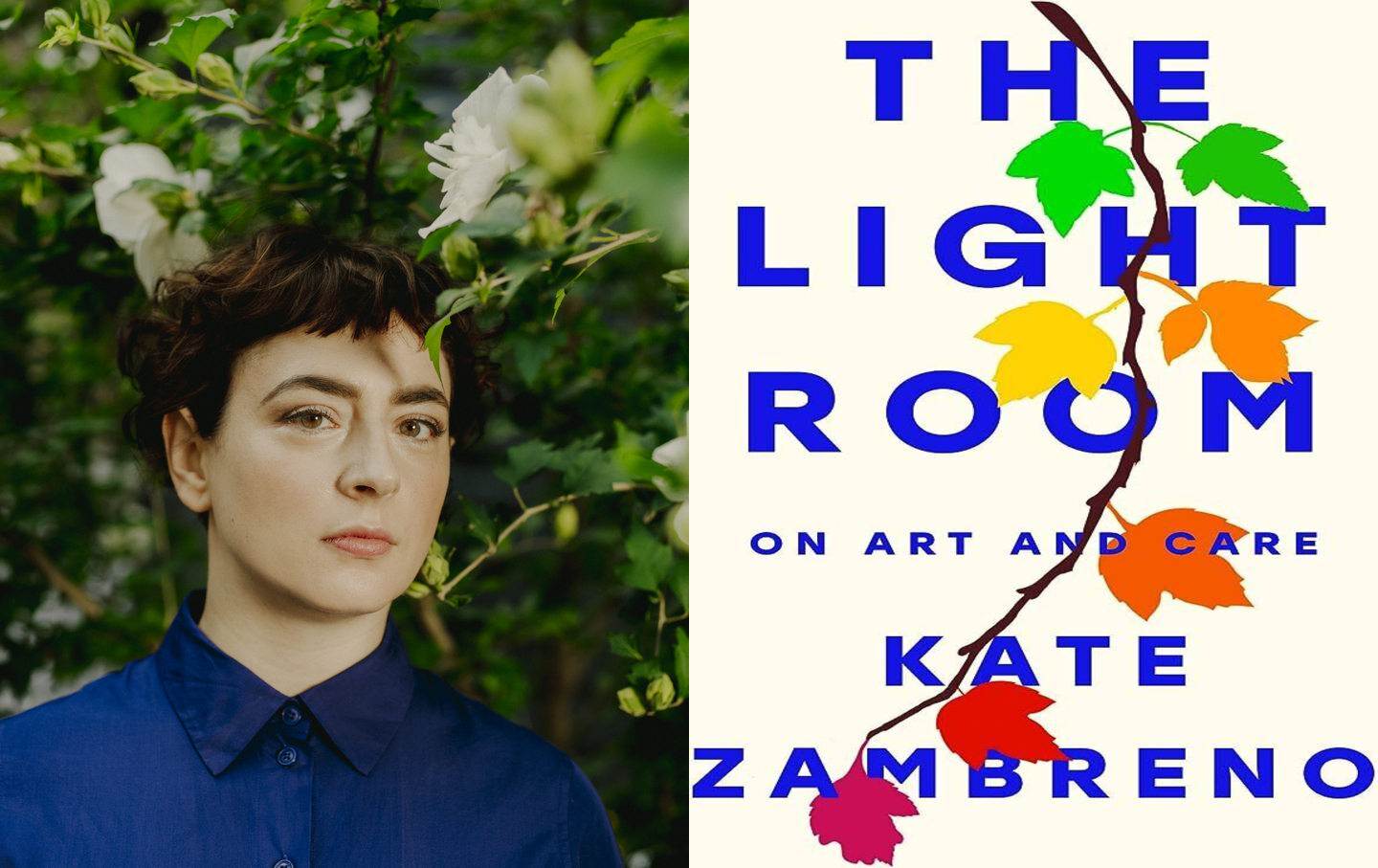

Kate Zambreno’s Lessons in Looking

A conversation about how the pandemic changed our relationship to the natural world, distrusting beauty, the challenges of writing about climate change, and her new book, The Light Room.

Kate Zambreno’s The Light Room is a book of boxes, surfaces, and close observation, set during the first two years of the Covid-19 pandemic. The book is divided into several distinct sections: the first, “Light Boxes,” is the most intimate, pairing scenes of the close and cluttered domestic interior with outings to Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, which serves as a school and a sanctuary. Through accumulation, a portrait of the early days of the pandemic—and of parenting a newborn—emerges. Zambreno’s eye in these moments is fine-tuned: The impression is of dust motes illuminated in a ray of light. “The snow is so beautiful,” Zambreno writes. “I watch it from the window. It falls so fast. The baby is asleep on me. Her body is changing. The circle of fat at her wrist is disappearing. Soon she will be toddling after her sister, building cities.”

The book, which is not quite memoir, not quite an experimental novel, but a text that synthesizes multiple ways of looking at the same thing, incorporates Zambreno’s affinity for research and notebooking. She cites artists and writers as varied as Joseph Cornell, David Wojnarowicz, and Yuko Tsushima, whose novel Territory of Light informs her reflections on motherhood.

I talked to Zambreno about The Light Room, atmospheric disturbances, nature writing, the end of capitalism, and much more.

—Larissa Pham

Larissa Pham: Why did you choose to shift from the first to the third person in the book?

Kate Zambreno: In the past couple of years, I’ve been really trying to interrogate the first person. I think sometimes someone writes to just try to figure out why they write. And I think that I’ve really tried to examine what the first person is. It is hopefully a space of inquiry and curiosity that can gesture to something larger. I’ve tried to gesture to precarities, and the relationship with the self under capitalism, and the boundaries of the self.

I still really believe in the first person, but I am skeptical of it. Which is, I think, why I keep writing it. “Translucencies,” the part of the book told in third person, is playing with what and who is the third person? What does it do? How does that defamiliarize our ideas, or my sense of what I’m writing? Something like an estranging form of memoir. I was really inspired by the idea of a photograph becoming a third-person fiction. What does it mean to think of yourself as a character?

LP: I feel like the “I” is so tied to the body. And in those early sections, which are in first person, it’s very much about your body, or like your children and your body, and the baby and the body.

KZ: My writing has been tremendously shaped by having children. Because it’s been a sort of enforced solitude for me. There’s a level of privilege I’m speaking from, because it’s very hard for a lot of mothers to write at all. So I am part of a two-parent form where we co-parent, you know, we try to work through a division of labor with that. And my writing happens in the spaces where I can create physical solitude for myself. The forced solitude of the naptime, for example, was a monastic existence for me, where everything went away. I think that’s why so many of my works come from the notebook. The notebook became its own little room that I could fit into myself.

LP: Hearing you speak about the notebook as a space, what is the relationship between making notes and writing notes and then—these products that come to people like me?

KZ: I think that publishing not only creates the I as this alienating presence, this I above all other I’s individualism, but also this idea of the big book.

There’s probably no mistake that the artists I write to in The Light Room are incredibly interested in the serial form. May Sarton, her series of journals; David Wojnarowicz, the interconnectedness of all his different forms and genres. And then Joseph Cornell, who repeats throughout the book. He would make one box, but he couldn’t just make one box. It wasn’t the only box, it was a series. The box didn’t fulfill it. And it wasn’t about selling it.

These artists that I’m looking at are more interested in the private ritual of the series, or the documentation. The idea of the one and it has to be big—that’s the commodity form. It is pretty alienated from how I view my own work. I do think of the shape of a work. I do want to give it shape. I think about its form; I want to finish it. It is over a certain period of my life, usually, and usually the works don’t intersect. But it’s not as though I’m like, this one’s nonfiction, so it’s this, and this one’s fiction, so it’s that. Those are often just ways people agree to publish me. I don’t think of The Light Room as memoir. I don’t think memoir is bad. I think my work is obviously interested in memoir. I’m interested in memoir, I’m interested in memory. But why are we memoirists? Publishing’s tendency is towards flattening.

LP: I wanted to ask you about this thread that you pick up toward the end of the book, which is about early childhood education. And toys, and beauty, and—the role of beauty, in the world and for children. And I see it as consistent with the rest of your work in terms of wanting a life of the mind, wanting family, and the desire for beauty, amid all the pressures of daily life, seems so indulgent in some ways, but it’s also so necessary.

KZ: Beauty as an aesthetic quality is something to hold suspect, as a moral quality, as a quality so dependent upon capitalism in so many ways. So my desire for aesthetic beauty, I think, is also suspect. But it is about trying to pay attention. I think the main thrust of this book is trying to pay attention, to find beauty in a world that’s quite diminishing. And in an environment that is so often shabby and cluttered, in a domestic world that is so chaotic. The desire for beauty is a little bit like the desire for joy, which can be easily co-opted or commodified. But joy is hopefully a release from capitalism, even if for a temporary second. A relief from overwork. Just the ability to actually pay attention or to take care of something.

LP: I found that in my own life, I became much more attuned to the natural world during the pandemic. And similarly, I didn’t always think of you as an ecological writer, but that really came to the front in this book.

KZ: I didn’t think of myself as an ecological writer. But I became interested in writing about animals and zoos. I started to be interested in how to write the local, the neighborhood. And a lot of how I taught ecological writing to students was thinking about attention and care. My students took walks around their neighborhoods when they were living in their childhood bedrooms, and were observing the weather patterns where they were, which is a very serious subject, now, especially. This is the first year I’ve taught it in person, and we’d walk sweetly down the grass together on campus, we’d observe certain trees. I think that has changed me as a writer.

LP: Thinking about the environment, and weather, I’m reminded of how our self expands much further than the boundaries of our bodies.

KZ: We are so porous. We’re breathing each other’s air. I mean, I think the pandemic should hopefully be a lesson in that. So many people became more private and insular. Secured their own bubbles, their own air-conditioned units away from people. One of the lessons of the pandemic, or from even this recent atmospheric disturbance where we’re literally breathing air that’s from Canada, is that we have to start thinking of how porous we are. And we have to start thinking of all of us together.

LP: I’m actually curious now, hearing you speak about this, because I personally don’t see your work as political—I don’t see you as necessarily writing in a tradition of political, argumentative writing.

KZ: No. Although Heroines maybe has something in common with Andrea Dworkin’s Intercourse or Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto. I think there’s a manifesto quality to Heroines, like there’s a rawness to it. The early works like O Fallen Angel, Green Girl, Heroines, have much more of this agitating quality.

LP: I’m curious how you would locate this more recent work within contemporary politics—be it the climate or critiques of capitalism?

KZ: I’m very interested in precarities. I’ve always been very interested in the material conditions of being a writer and how one survives as a writer, and thinking of labor as essentially political. How to live a life? We’re still under capitalism. We’re overworked and precarious. How can we still live life? And how do we live life? For example, the landlord-tenant relationship, or the hierarchies of wealth and privilege—I think that’s essentially political. I think writing a first-person story that’s as intimate and based in reality as possible, especially if you are living in some level of precarity, that’s essentially political, too. It’s not seen as political because it’s seen as intimate and interior. Like these Japanese women writers, like Hiroko Oyamada, she’s writing often about young women working amidst this ambience of patriarchy. And it’s that ambience which is not often seen as political in so many first-person works by women, which are about that ambience.

if you’re writing about that ambience or of cruelties, and how one survives amidst these cruelties, I think that’s essentially political.

LP: I feel like it’s very important also just in a literary sense to think about how the shape of a book does not necessarily need to be built around a climactic event that is particularly cruel or particularly devastating.

KZ: That’s right. Someone once said to me—I thought this was very helpful—they said, You know, it’s very interesting that you write about sadness. I thought, Oh, I do write about sadness. And sadness is not seen as political. But I think sadness is very political. Like to write ugly feelings, what Sianne Ngai calls ugly feelings. Sofia Samatar and I had a conversation about irritation in Nella Larson’s Quicksand. Nella Larson’s narrator is not seen as political or the books aren’t seen as political in a way because she’s just irritated. But that irritation is a very important emotion. Because it’s chafing against this ambient racism, ambient patriarchy, classism. So I think, to me, my works often are about these negative feelings, like sadness, or ambivalence or irritation. But I think they’re about how we live.