Two hundred thousand boys and girls will be in uniform when Dixie Youth Baseball begins its 66th season this spring. Everyone will stand for the national anthem. Players will be introduced by name before the home team takes the field. The players’ parents, grandparents, brothers, and sisters will fill the bleachers and cheer as families have done for decades—and the players’ uniforms will never again be as white as they are before the first game.

Dixie League Baseball, one of the most popular youth baseball organizations in the country, is played in the 11 states that once embraced the Confederacy. Few of those players or their parents probably know that the league is a relic of Jim Crowism—or that it was founded on the heartbreak and tears of a team of 11- and 12-year-old Black boys, the Cannon Street YMCA All-Stars of Charleston, S.C.

When the Cannon Street All-Stars, the first Black little league in South Carolina, registered for the district tournament in Charleston in July 1955, it put the team and the forces of integration on a collision course with segregation, bigotry, and the Southern way of life. The Cannon Street team won the tournament by forfeit after all the white teams withdrew in protest. It then advanced to the state tournament.

Danny Jones, the state director of Little League Baseball, told Peter McGovern, the organization’s president, that he wanted a segregated tournament. McGovern rejected Jones’s request, saying that Little League Baseball’s rules prohibited racial discrimination. He said that Jones and all the coaches had agreed to those rules when they joined the organization. Any team that refused to play the Cannon Street All-Stars would be banned from Little League Baseball, McGovern said.

The 61 white teams withdrew from the tournament. The Cannon Street team won by forfeit and advanced to the regionals in Rome, Ga., where the state’s governor, Marvin Griffin, had warned of the consequences of integration. If youth baseball could be integrated, so, too, could schools, municipal parks, and swimming pools. “One break in the dike,” Griffin said, “and the relentless seas will rush in and destroy us.”

If the Cannon Street All-Stars won in Rome, they would play in the Little League World Series in Williamsport, Pa. But the tournament officials ruled the team ineligible because it had advanced by forfeit and not by winning on the field, as specified in the organization’s rules. McGovern affirmed the decision. This ended the season for the Cannon Street All-Stars.

Jones resigned from Little League Baseball in protest after being told he couldn’t have a segregated tournament and created the Little Boys League. The organization mandated segregation in its charter and put the Confederate flag on the cover of its rule books and on the uniforms of its players. Jones became the organization’s first commissioner. More than 500 teams in 120 leagues signed up for the 1956 season. As the Little Boys League expanded, Little League Baseball all but disappeared from the South.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Little League Baseball’s civil war was part of a larger response in the South to the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which ended school segregation and provided the legal framework for the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. White parents saw no difference between white and Black boys sharing the same baseball field with one another and white and Black children sharing the same schools.

“The prospect of integrated Little League tournaments struck a raw nerve among white parents enraged by Brown’s threat to the existing legal and social order,” wrote Douglas Abrams in a 2013 article in the Journal of Supreme Court History. “Images of black schoolchildren such as the Cannon Street All Stars playing organized baseball against whites evoked reactions similar to images of black schoolchildren sitting side by side with classmates.”

Little League Baseball sued the Little Boys League for copyright infringement and the organization became Dixie Youth Baseball. Dixie Youth Baseball itself became integrated in 1967. The Confederate flag remained on the league’s all-star uniforms for another quarter-century.

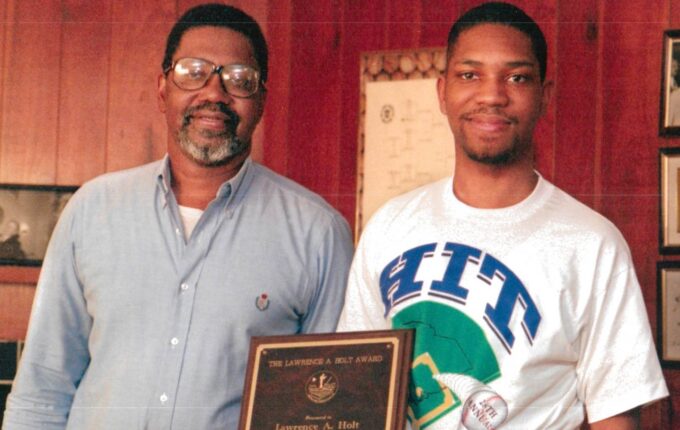

The story of Dixie League Baseball’s racist past would have remained buried had it not been for Augustus Holt, a Charleston civil rights activist. In 1993, Holt’s son, Lawrence, made the all-star team in the Dixie Youth Baseball league and proudly stood in front of his father in his uniform.

Holt’s smile disappeared when he saw the patch of the Confederate flag on his son’s uniform. He investigated how the Confederate flag—a symbol of white supremacy—had ended up there. He learned that Dixie Youth Baseball “had been founded on the tears of the Cannon Street players.”

Holt then revived Little League Baseball in Charleston and organized a reunion of the Cannon Street YMCA All-Stars. In 2002, Little League Baseball invited the team to Williamsport and apologized for its part in their pain, giving a measure of redemption to the men in their 50s.

When asked about the league’s history three years ago, Wes Skelton, who was then commissioner of Dixie Youth Baseball, said the Cannon Street team was ruled ineligible for the state tournament because it violated the rules of the organization. “As far as I know, they hadn’t played together all year. They just formed the team,” Skelton said.

But this was the case of all the teams in Little League tournaments, where coaches selected the best players in the league for an all-star team. It was, in fact, Danny Jones and the white coaches who violated the organization’s rules, which required teams to abide by the stricture against racial discrimination

Dixie Youth Baseball continues to honor Jones, who remained the organization’s commissioner until his death in 1966. The organization gives the Danny Jones Sportsmanship Award to the team in its post-season tournament that “demonstrates the character and traits for which this program was organized.”