The Banal Spectacle of Avatar: Fire and Ash

The Banal Spectacle of “Avatar: Fire and Ash”

Has James Cameron’s epic sci-fi series run aground?

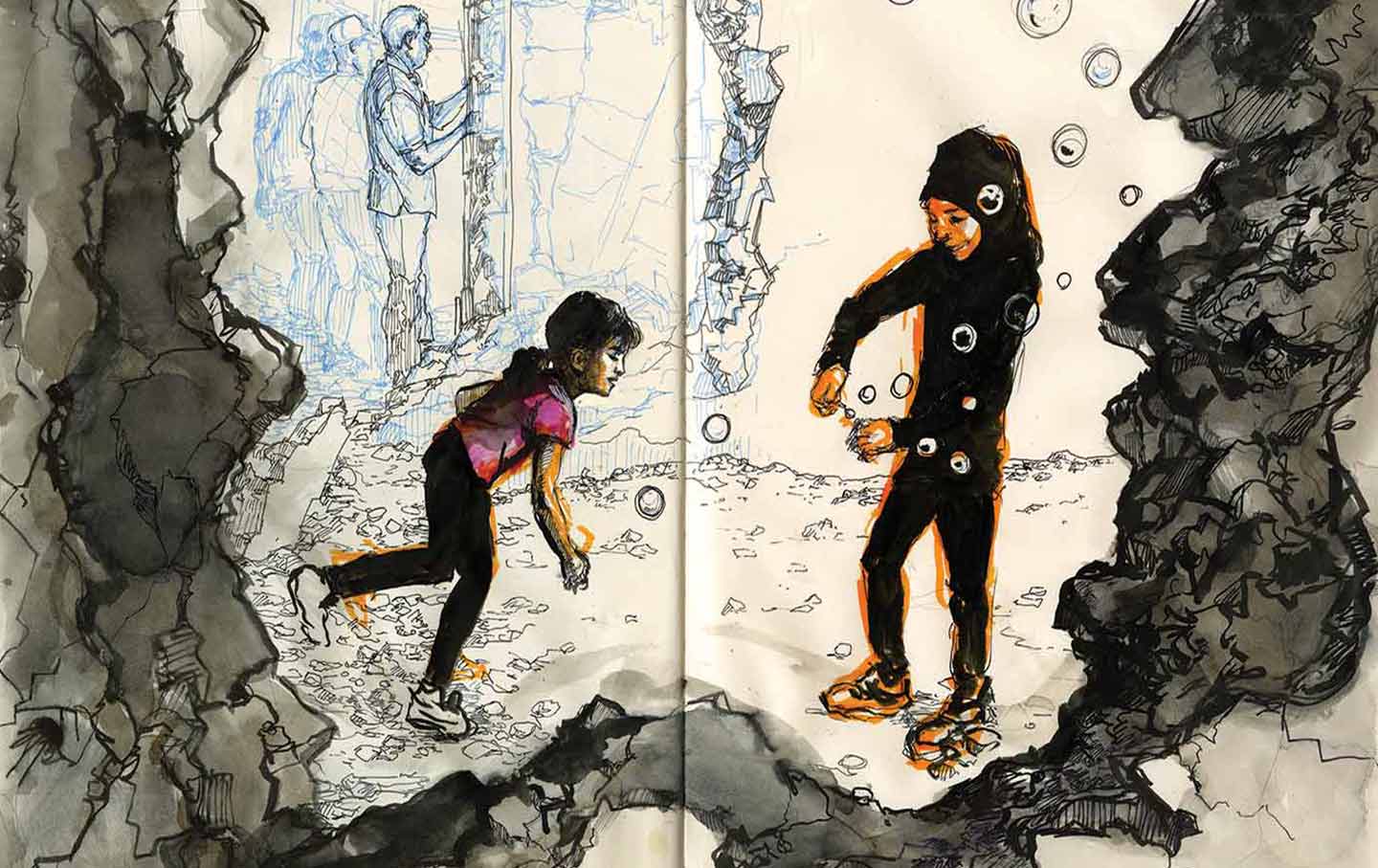

James Cameron’s latest Avatar movie opens with a scene of innocent wonder. Two young brothers soar through the air on winged beasts, taking in the vertiginous views of their majestic home world. Both are Na’Vi, lithe bipedal inhabitants of the verdant moon Pandora introduced back in 2009 in the series’ first entry. The boys experience Pandora as a playground, its psychedelic flora and fauna a boundless source of delight. The catch is that one of the brothers is dead. The shared flight is possible only because a ritual (and literal) connection to nature and their world’s shared memory allows the living one, Lo’ak (Brian Dalton), to commune with his older sibling, Neteyam (Jamie Flatters). For the Na’Vi, the environment is kindred, so much so that a special organ lets them link to the planet itself.

That bond, and the transcendental encounters it makes possible, are threatened in Avatar: Fire and Ash. In Cameron’s third trip to this edenic land, the conflict between the conscientious Na’Vi and the greedy, spacefaring earthlings of the first two films has escalated into full-blown warfare. In the previous movie, 2022’s Avatar: The Way of Water, Neteyam died in a climactic battle between the humans and the Na’Vi, a loss that haunts the sequel. Now his surviving family, the Sullys, must mourn Neteyam while rallying to fight for the future of Pandora.

These themes—war, grief, colonization, environmental calamity—are the stuff of epics, but Cameron can’t escape bland allegory. The Na’Vi, already a thin puree of New Age woo-woo and stereotypical indigeneity, get further diluted in Fire and Ash. In an attempt to complicate his noble savages, Cameron introduces ignoble ones: the Ash people, a group of pyromaniac Na’Vi who’ve turned against their kind because their village was destroyed by a volcanic eruption. When the Ash people team up with the humans, Pandora for the first time faces both internal and external threats. But the new antagonists only further underscore how thinly the Na’Vi have been portrayed since the first movie.

Fire and Ash cements the emptiness of Avatar. The blockbuster series is supposed to be about clashing civilizations and their disparate relationships to nature, but across nine hours of screentime, it has relied on rigid binaries: machine versus organic, alien versus native, science versus magic. Cameron’s incurious characters rarely seek out third (or fourth) positions or express and experience wonder on their own terms. Since it ushered in the modern age of 3D filmmaking back in 2009, Avatar has been touted as a series to look at, to get lost in. But the deeper Cameron plunges into this fictional universe, the shallower it proves to be.

Fire and Ash ramps up quickly. After opening with the brothers in flight, the film checks in with the rest of the Sullys, who are also struggling to cope with Neteyam’s death. Stoic dad Jake (Sam Worthington), the former Marine who became a Na’Vi in the first film, broods and compiles weapons for the coming battles. Meanwhile, warrior mother Neytiri (Zoe Saldana) seethes, casting foul glances at their adopted son, Spider (Jake Champion), a human raised among the Na’Vi who’s essentially a teenage Tarzan. And flowerchild Na’Vi Kiri (Sigourney Weaver), another adopted Sully, longs to reconnect with nature, which has mysteriously shut her out. Concerns about Spider’s ability to breathe, which requires gas masks because Pandoran air is toxic to humans, result in the family’s joining a convoy of “Wind Traders” to take him to an area safe for humans.

The Traders hint at a more complex story. Despite the winged creatures they’ve flown on since the first film, Na’Vi have previously been depicted as territorial, rarely venturing far from where they roost. It makes you wonder: Is there a Na’Vi economy? Do they exchange information about the encroachment of humans? How far apart are these communities?

Cameron glosses over such possibilities, instead relishing the otherworldly spectacle of the carriages, which are designed as a kind of organic steampunk hot air balloon. Flying creatures reminiscent of manta rays pull the vessels, while the “balloons” resemble pearlescent jellyfish. It’s certainly a sight, but after the Ash people attack the convoy, the story leaves behind the traders, and any interest in wider Na’Vi perspectives.

From there, Fire and Ash becomes an elaborate game of cat and mouse as the Sullys elude central antagonist Quaritch (Stephen Lang), a commando reborn in The Way of Water as a Na’Vi hell-bent on capturing Jake. Quaritch casts Jake as the ultimate species traitor, boasting, “Doesn’t matter what color I am, I remember what team I’m playing for.” But he finds himself venturing down the same path as his nemesis: Like Jake, Quaritch has become increasingly comfortable with Na’vi ways of life despite his allegiance to Earth, an irony that deepens when he falls for the fiery Varang (Oona Chaplin) of the Ash people. They bond over their mutual bloodlust, with Quaritch suggestively vowing to help Varang “spread your fire across the world.”

Quaritch’s human son, Spider, a minor character in the previous film, becomes a centerpiece, one of the film’s thorniest turns. Through a twist, he becomes able to breathe the planet’s air, which makes him a high-value target for the humans. If they can reverse-engineer the process that lets him breathe, human colonization can ramp up. Neytiri, fearing that outcome and motivated by a growing hatred for humans, suggests killing Spider, a move Jake opposes and later considers. Spider, meanwhile, feels increasingly attached to Pandora, and even grows the Na’Vi organ that allows communion with nature, muddying the line between native and alien.

There’s a lot going on here: contested paternity, purist ideas of kinship, extinction, racial allegiance and grievance. But the film rarely slows enough to push these threads in fruitful directions, always charging toward the next big battle or twist. Cameron’s understanding of difference is too simplistic to make these shifting views feel revelatory. We see this when the Ash people enlist with Quaritch in exchange for guns. As part of the arrangement, they move to Pandora’s human hub, and have no trouble adjusting. Likewise, when Spider is captured and taken to that same city, the story speeds through what should be a dizzying predicament: Spider is among his species, but these are not his people, all while poised to be the savior for his homeland and the destroyer of his adopted one.

There’s little internal turmoil amid all the body-hopping and species-mingling. Cameron’s characters bicker and fight without ever transforming, often giving hokey reasons for their inertia. “The people say that when you touch steel, its poison seeps into your heart,” Lo’ak says at one point, describing an arbitrary Na’Vi prohibition against metal. The Na’Vi have literally been invaded by aliens, but Cameron can only imagine them as folksy mystics.

The failures of Fire and Ash are all tied up in that strange and artificial fixity of the Na’Vi. Over the course of the series, they have experienced human colonization for decades—enough time for humans to build a city, for businesses on Earth to be involved in intergalactic extraction of Pandoran resources, for some Na’Vi to learn English, and for Jake, a former human, to start a family. But this history has the barest footprint. Na’Vis call humans “Sky people” and “pink skins,” shorthands that signify racial difference more than planetary or political divergence. Speaking of planets, despite living on a moon, the Na’Vi oddly don’t even have a cosmology: We never learn the name of the planet the moon revolves around, or learn Na’Vi beliefs about what lies beyond Pandora’s atmosphere. Cameron gives them a religion, a global spirit they call Eywa, but their conception of nature is ultimately terrestrial and static, bound to the soil. That choice reveals how flatly Cameron imagines his hero race.

That flat vision lingers even if you try to enjoy the popcorn thrills of Fire and Ash. Yes, it boasts the bleeding edge of digital effects, and is relentlessly filigreed with textures and colors. Although it was shot at the same time as The Way of Water, Fire and Ash is even more dazzling: the flame motif results in chiaroscuro shadows and lighting even in underwater scenes. And the attention to detail is exquisite: At one point, a whale-like creature with septum piercings breaches water to speak with the Sullys, and when she speaks, the water around her ripples and splashes in perfectly imperfect concentric circles. The level of scrutiny applied to this story’s visual environment is endlessly stunning.

But that precision ultimately makes the innate flaws of the saga more unbearable. Despite how much more richly rendered the world has become across three movies, the denizens of Pandora have not been granted much interiority or depth: Cameron’s Na’Vi are virtuous stewards of the landscape; his humans are warmongering brutes. Pandora is a lush paradise, while Earth, which we never see, is a wasteland that’s just industrious enough to maintain interstellar capitalism. He attempts to invert those dynamics here with Spider, a valiant human who wants to be Na’Vi, and the Ash people, crazed fiends who want to make Pandora a wasteland, as well as the various arcs of the Sullys.

But the positions the characters can inhabit, the thoughts they can think and paths they can take, remain circumscribed—a determinism at odds with the romance and whimsy Cameron tries so hard to stoke. Fire and Ash is the dullest kind of science fiction, intricate but uninquisitive, sprawling but close-minded, the story never evolving past Cameron’s backhanded love for Indigenous environmentalism and fondness for loud, gee-whiz action. No matter how ornate the CGI gets, this series sticks to the same offensive premise: cowboys and Indians.