As government leaders, environmental experts, and concerned citizens from around the world gathered last week in San Francisco at the Global Climate Action Summit, a message has emerged from progressive activists: Action on climate change is about more than just power plants or temperature goals. The climate movement has become a powerful political force, with tens of thousands of people from across America’s largest cities and smallest communities calling for an end to the unsustainable use of fossil fuels—but now the call includes plans that create jobs and address the possible disproportionate effects on marginal and at-risk communities. Progressive politicians are following their lead, increasingly realizing that the only way to equitably meet the challenge of a clean-energy revolution is a 21st-century economy that guarantees clean air and water, modernizes national infrastructure, and creates high-quality jobs.

Insurgent Democratic candidates have been the rock stars of the 2018 election cycle, with large parts of the progressive agenda rocketing up the charts with them. And key to that agenda is these candidates’ embrace of activist positions on climate change, jobs, and environmental justice. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—who caught the nation’s attention with her inspiring primary win over a member of the Democratic House leadership, Representative Joe Crowley—includes in her platform “transitioning the United States to a carbon-free, 100-percent renewable energy system, and a fully modernized electrical grid by 2035.” Randy Bryce—the hard-hatted, union-backed veteran known as “IronStache”—is running to take the Wisconsin seat being vacated by House Speaker Paul Ryan. He calls for a “massive investment in green infrastructure that would generate tens of thousands of new jobs,” bring an end to fossil-fuel use, and build community resilience.

Similar initiatives are championed by Michigan Democrat Rashida Tlaib, who is hoping to be the first Muslim woman elected to Congress; Andrew Gillum, the Democratic nominee who could be the first African-American governor of Florida; and Kevin de León, who is up against 26-year incumbent US senator and Democratic institution Dianne Feinstein in California. Their proposals vary in form and potential, but they each fall under the same banner.

They call it a Green New Deal.

The name draws on Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal economic reform and job programs of the 1930s. The novel environmental framing has been traced back to a decade ago, when New York Times columnist and hardly man-of-the-left Thomas Friedman used it to call—in a distinctly capitalist context—for caps on emissions and an end to fuel subsidies. But today, in the hands and on the platforms of a new wave of activist candidates, the Green New Deal has become something more comprehensive and ambitious. A new report by Data for Progress outlines this vision, demonstrating that, like in FDR’s time, this new deal is one that should energize progressive voters.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The Green New Deal is a broad, yet specific, set of policy goals and investments that blend environmental sustainability and economic stability in ways that are both just and equitable. First, the study factors in the best current research to ensure the components of a Green New Deal meet the urgency and scale of our greatest environmental threats: heading off further climate change by taking fossil fuels out of the economy, restoring our forests and wetlands so they can suck more carbon out of the atmosphere, and finishing the job of cleaning our air and water. Second, a Green New Deal is about bringing sustainability and stability to the economy. This means sustainable agriculture and zero waste, upgrading our infrastructure and urban transit systems, and building up resilience to the severe weather disasters in both urban and rural communities.

Third, a Green New Deal is a job creator. Targeted investments in clean energy, energy efficiency, reforestation, and construction will generate private-sector green jobs. The combination of training and a green-job guarantee ensures there is employment and a livable wage waiting for anyone who wants to join the 21st-century sustainable, clean-energy workforce. Finally, and most importantly, a Green New Deal is founded upon principles of equity and justice. The goal is to avoid the past mistakes of similar initiatives by resolving the inequities felt by those—particularly in low-income, indigenous, and minority communities—who historically endure a greater share of environmental harm and receive fewer benefits.

This is what makes the Green New Deal different. Environmentalists who might have once ignored economics and equity have learned the hard lessons of the past. In the state of Washington, for example, Ballot Initiative 732 was a first-of-its-kind carbon-tax law in 2016—however, it lost support by failing to provide for investment in the most vulnerable and hardest-hit communities. A revised initiative, 1631, which promises investments in green programs with immediate economic benefits, heads to the ballot this November. With broader support and a better chance of passing, it could provide a roadmap for beating back opposition from powerful fossil-fuel lobbies. This year, seven state houses—in Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington—have seen the introduction of carbon-pricing legislation with some consideration of equity.

And that’s a start, but organizers and progressive candidates who recognize the stakes this election cycle are infusing environmental lawmaking with a sense of urgency that inspires more than incremental steps. The Trump administration has pulled out of international accords on climate change while moving to bail out the coal industry and roll back air-pollution regulations—actions that could cause thousands more premature deaths each year.

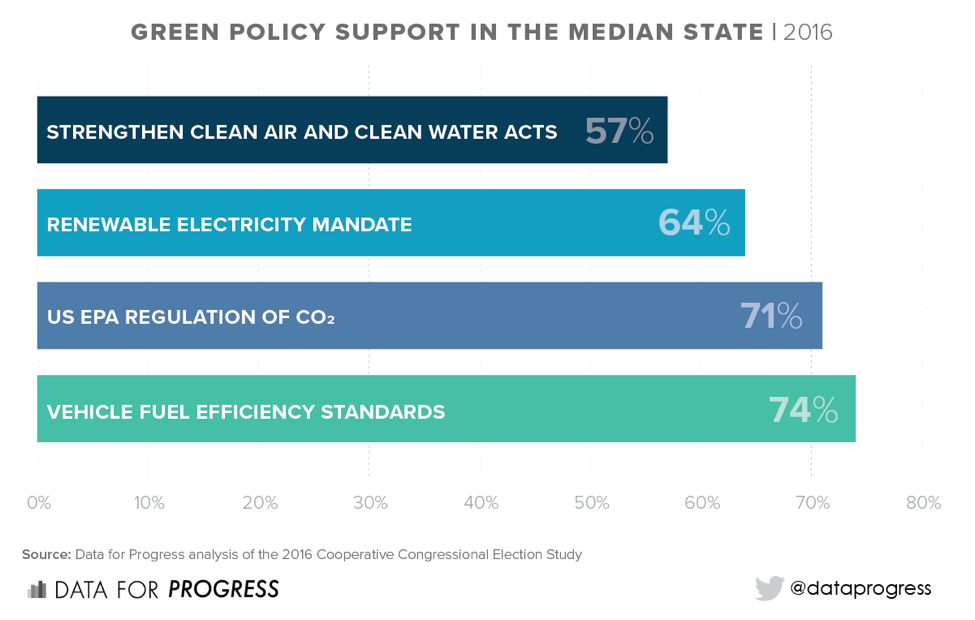

But the federal government’s hostility to environmental stewardship could prove to be progressive candidates’ opportunity. The Data for Progress report analyzed the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study survey results, which asked about political attitudes and policy support during the 2016 election cycle. The chart below shows specific environmental policies that have greater than 55 percent support in the median state, topping out with fuel-efficiency standards garnering 74 percent. (We analyze the median state to give a better sense of the middle of America, because polarized opinions can skew a national average and are not distributed evenly across the country.)

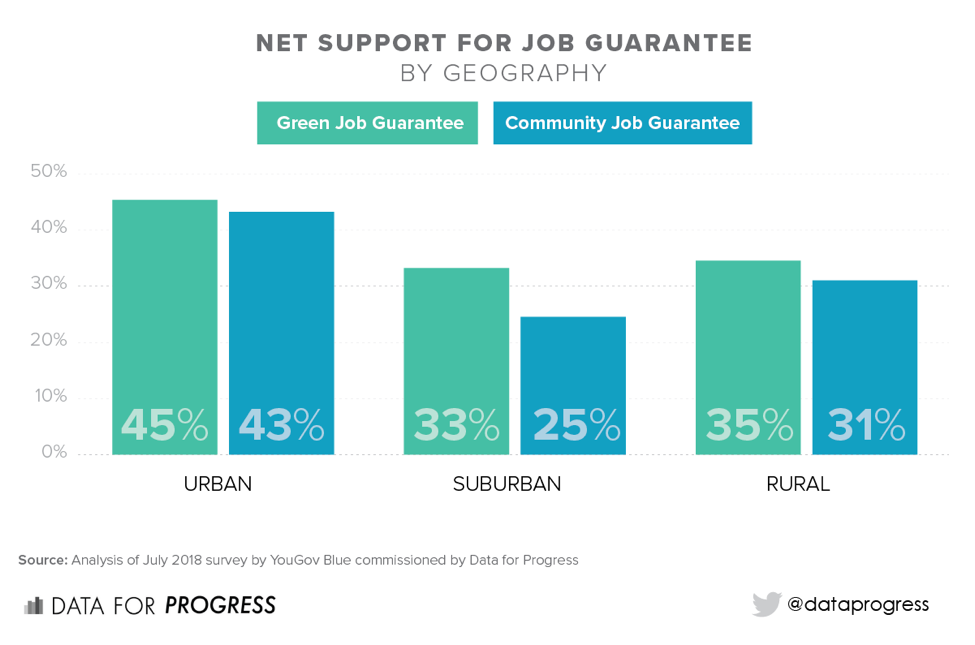

We also analyzed results from a public-opinion survey commissioned in July 2018 by Data for Progress and the advocacy groups Sunrise Movement and 350 Action. One question asked about support for, or opposition to, community job creation, for both generic jobs and green jobs. While 55 percent of Americans support both generic and green job creation equally, the green-job framing elicited far less opposition: 18 percent, compared to 23 percent for generic job creation. Green jobs also performed well across across all age groups, particularly among young voters, as well as across geographic demarcations, garnering high net support among urban, suburban, and rural populations. The analysis (with interactive maps) suggests that such policies would have strong support across the country.

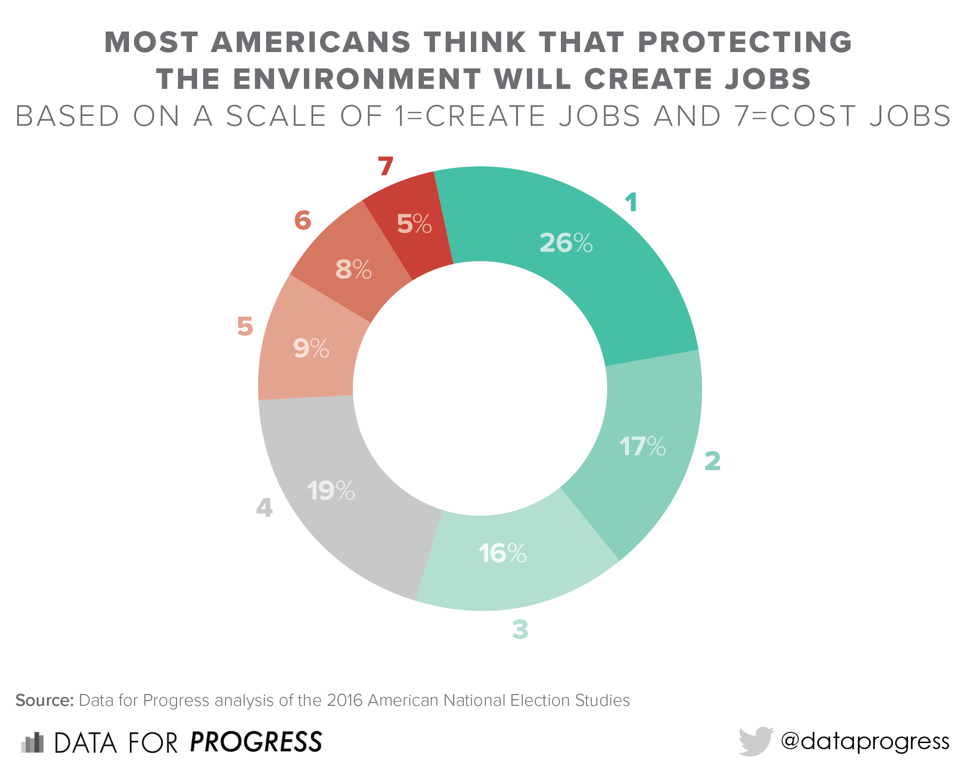

A message around green jobs would help progressives combat the myth that environmental policies harm workers. However, even the concern that voters buy in to this myth is overstated. Also in the American National Election Studies 2016 results, which Data For Progress analyzed, were opinions on whether environmental regulation creates jobs or costs jobs: Fifty-eight percent of Americans felt that protecting the environment would create jobs–while only 22 percent felt it would decrease the number of jobs.

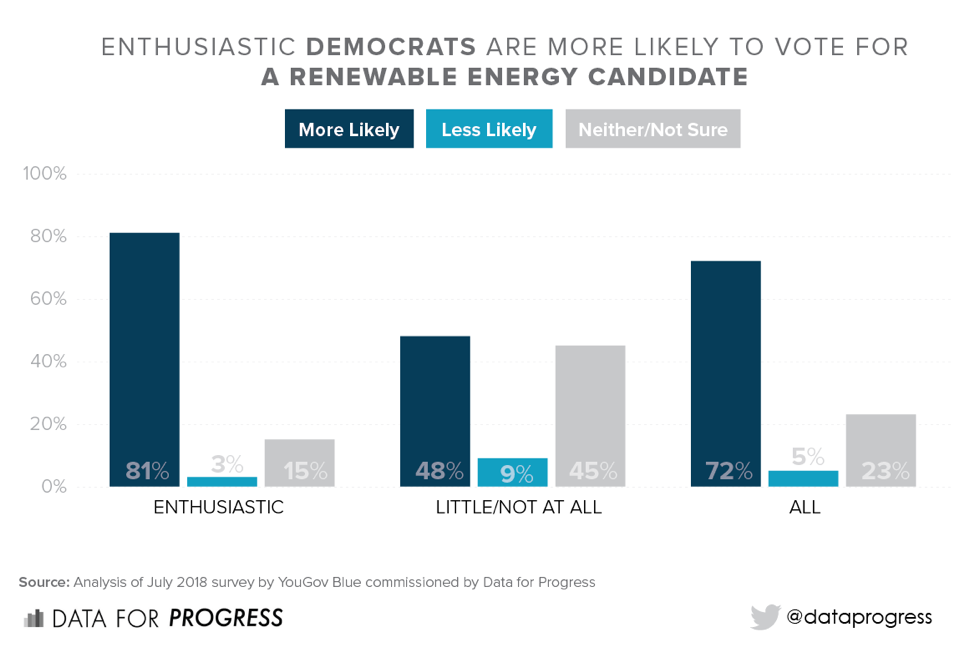

The more important question, however, is whether these preferences will change votes or turnout on Election Day. We also found signs this could be the case. Among eligible voters who expressed enthusiasm for the 2018 elections, 55 percent said they are more likely to vote for a candidate who supports a green-jobs guarantee. And 52 percent said they are more likely to vote for a candidate backing a 100-percent renewable-energy policy. Support for both policies jumps to 81 percent when questioning Democratic voters.

Not only is a Green New Deal practically feasible, it’s also politically feasible, especially in the Democratic party.

A Green New Deal is more than a smart carbon tax or some environmental regulation. It is one part of a progressive vision that strives to actually create the much-talked-about but still-painfully-absent 21st- century economy—with millions of living-wage jobs and justice for all. It also just happens to have the added benefits of mitigating climate change, guaranteeing clean air and water, and building community resilience.

Not a bad deal at all.