Rebekah Frank got into the food-service industry because of the freedom it allowed her: to travel, to go to school, to figure out what she might want to do later. She hopped among a number of different jobs in New York City—at a pub, a steak house, a celebrity chef’s restaurant. About three years ago, she got a job bartending in Brooklyn.

Soon after the job started, her manager told her to be careful about how much water she drank on the job, because male customers were going to grope her on the way to the bathroom. And they did, frequently grabbing her butt or hugging her while making offensive comments. “At least once every single shift, someone would whisper something absolutely foul into my ear,” Frank said. One guy told her that he had wet dreams about her every night. Another liked to tell her what he would do with her once he took her home. He was so persistent that she tried to get the six security guards on hand every night to kick him out, to no avail. “He was always there and always harassing me and always staring at me,” she said. “I would lie and tell him I was married, because it seemed like the only way to get him to not bother me.” The harassment went on for months; the man was only ejected from the bar after he got into a physical altercation with another male customer.

One night, a regular customer, whom Frank had considered to be a friend, offered to drive her home after work. “But he dropped me off at the house and stuck his tongue down my throat,” she said. She pushed him off. In the following weeks, he would hang out after the bar closed and whisper “the most crass, disgusting stuff” in her ear: how much he wanted to fuck her, how he couldn’t stop thinking about her. He sent her texts about how her Instagram photos made him hard.

The abuse took its toll on her. “It’s so disarming, no matter how many times it happens,” Frank said. She began breaking out in hives all over her body. Her thick hair started thinning out. Once, as she was walking to work, “all of the things that had happened caught up with me,” she recalled, and she had a full-blown panic attack; she became unable to breathe and lost sensation in her legs and hands. “And there’s nothing you can do about it,” she said. It wasn’t as if there was a human-resources department or someone designated to report problems to. These kinds of incidents are “so normalized; we experience them so much, and so much more when you work in this kind of industry,” Frank continued. “None of this is about sex, necessarily—it’s all about power. They’re not necessarily getting off on it; they’re showing us how small and insignificant we are and how our bodies aren’t ours. Even our ear canals aren’t ours.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Frank worried that speaking up would make her even less safe. When she finally told the owners of the bar about the incidents, they said they would say something to the customers. But that could escalate the behavior. “I always found myself in these situations where I’d be like, ‘This guy says things and it’s disgusting and I don’t like it, but is it going to make my life worse if I talk to somebody about it and they talk to him about it? Is that going to make my job harder, is that going to make me less safe, am I going to endure abuse of a different kind?’ You’re constantly weighing out these things. Not even what battle is worth fighting, but what battle is safe to fight.”

Frank felt particularly stuck because of the money she was able to make there—$400 to $500 a night, sometimes as much as $700, thanks to her tips. “I don’t want these men controlling my life, but at the same time they kind of were,” she said. At this bar, she added, “If you tell [a harassing customer] off, you don’t have any customers.”

Eventually, Frank left that job, though since then she has occasionally picked up shifts at that bar. Still, even going back to that neighborhood can trigger an anxiety attack. She now works days at a different bar in Brooklyn. “I am financially totally screwed,” she noted; tips are typically much lower during the day. But she faces far less harassment. “I actually feel like myself again.”

This is the bind that so many women who work in the country’s bars and restaurants find themselves in: The jobs are relatively easy to secure, offer a creative, unconventional work environment, and can even net them a sizable income. But far too often, that culture and that income are tied to putting up with sexual harassment.

Sexual harassment is a fact of life for far too many women across the economy, with about 60 percent saying they’ve experienced it. But the food-service industry is in a category all its own. In interviews with The Nation, many industry veterans struggled with how to describe the harassment or even where to begin, given how pervasive it was. (Several of the women whose stories are recounted below are referred to by first name only, due to privacy concerns.) Asking them to talk about it was like asking a fish to describe water. For the people who serve us dinner and drinks, it’s all but a way of life.

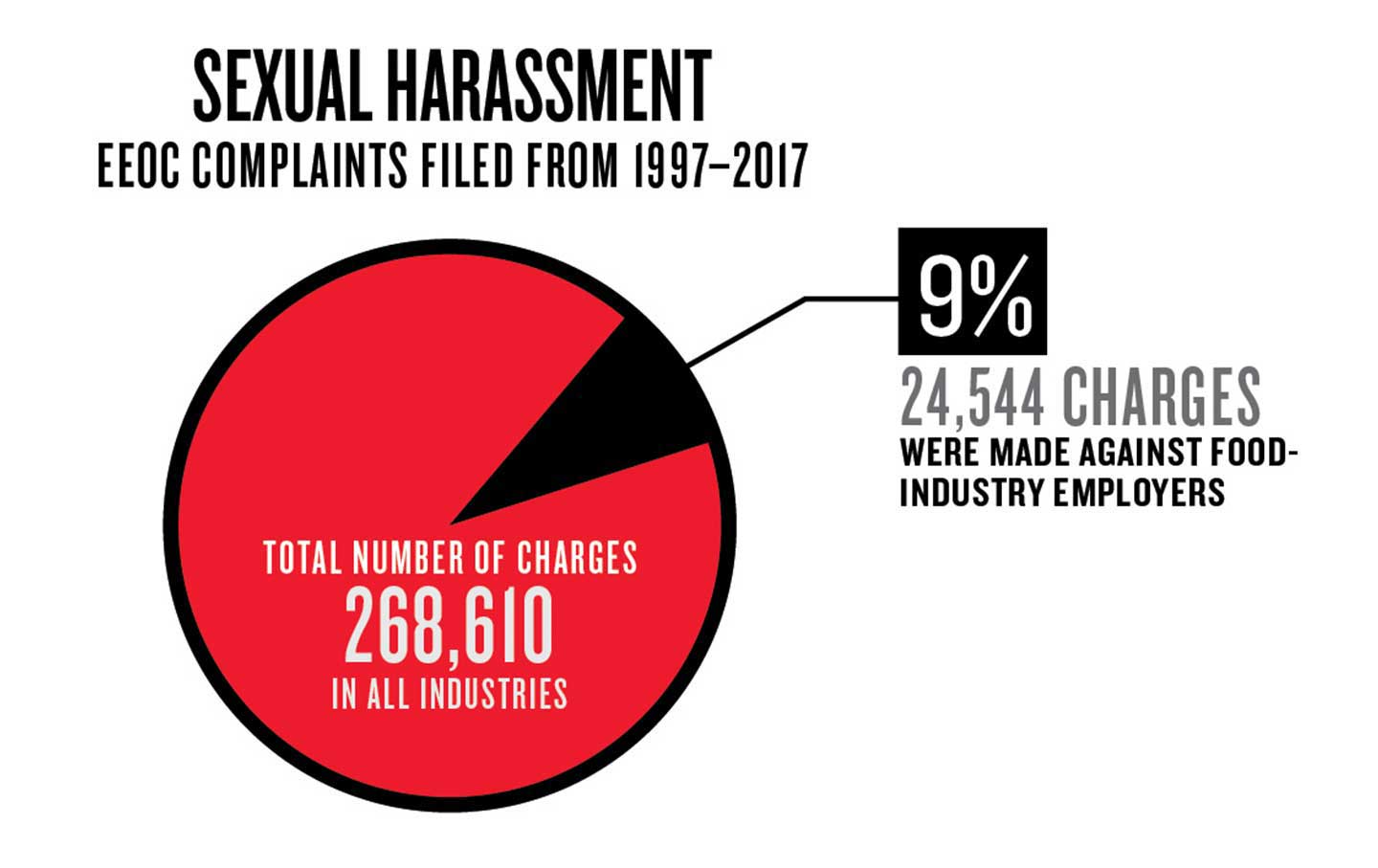

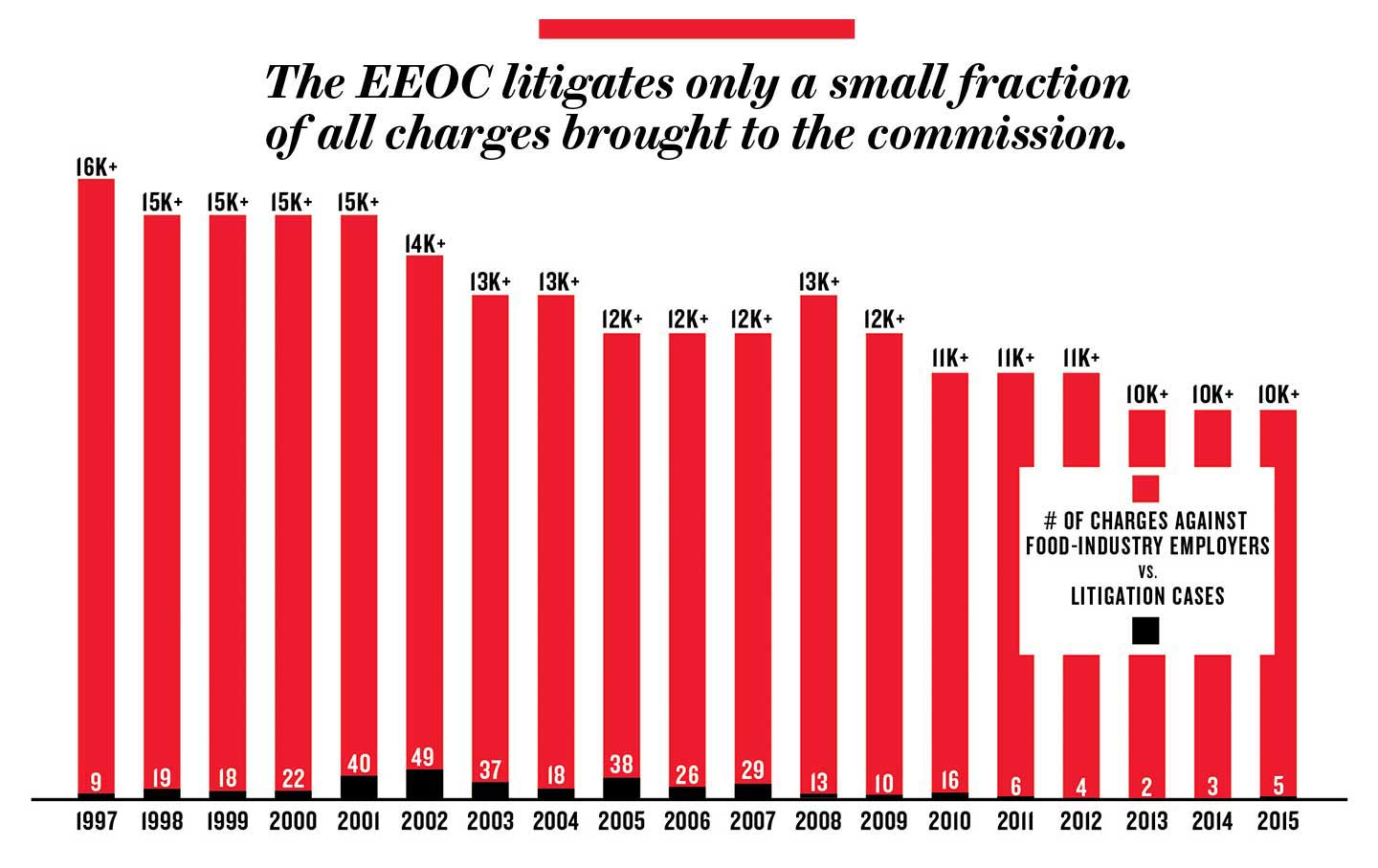

In a 2014 survey of 688 current and former restaurant employees, the Restaurant Opportunities Centers (ROC) United and Forward Together found that about 80 percent said they had been harassed by co-workers or customers. Another two-thirds said they had been harassed by managers. Sixty percent of female and transgender workers said that sexual harassment was an uncomfortable aspect of their daily work lives, while about a third said that being inappropriately touched was a common occurrence. A 2016 survey of women in the fast-food industry found that 40 percent had experienced unwanted sexual behavior on the job. In a recent study, 76 young women in food- and beverage-service jobs, followed over just three months, reported 226 incidents of sexual harassment. The accommodation and food-services industry—including bars, restaurants, and fast-food joints—was responsible for the largest share of private-sector sexual-harassment charges filed with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission from 2005 to 2015.

The food-service industry is a perfect storm of factors that foster harassment. It employs many young people, so inexperienced employees—sometimes teenagers—are often the supervisors in charge of addressing it; other young employees may not even know their own rights. Food-service jobs are disproportionately staffed by immigrants, who are more vulnerable to abuse. Employees are also easily hired and fired. The work can be repetitive, which is a risk factor for inappropriate behavior. Alcohol flows freely, and employees often spend time together late at night and after work. One unique culprit is servers’ heavy reliance on tips, which can incentivize both customers and co-workers to objectify women.

But despite the rampant nature of the abuse, there’s cause for optimism. In a new moment in which public tolerance for workplace harassment has dramatically decreased, food-service veterans and workers’ advocates are poised for action on multiple fronts involving sweeping cultural, legal, and policy changes that could completely reshape the industry.

At the Greek-owned restaurant in Virginia where Vanessa Fleming worked as a college student, her manager told her how to dress and act. “One time I wore a pair of pants, and I got in trouble because I’m supposed to be wearing shorts,” she recalled. “Halloween came along and I dressed up, and my boss really wanted me to be the upfront person because I had on a sexy outfit.” Physical appearance determined who got ahead and who didn’t. “I got a promotion to bartender because I was cuter; I got the better shifts on the cocktail bar because I was cuter,” Fleming said. “It’s this expectation…that we have to appease the men and acquiesce to what they want, and we’re just sexual objects, just there to be cutesy and flirty. The idea was: This is how it is—you deal with it or you leave…because serving jobs are a dime a dozen and servers are a dime a dozen.”

In most of the country, servers and bartenders can be paid a lower wage if their tips make up the difference between their pay and the federal minimum wage. The federal floor is just $2.13 per hour for tipped workers, versus $7.25 for everyone else. Tips from customers, therefore, have an enormous impact on what people earn. In a recent report, the National Employment Law Project found that tips account for nearly 60 percent of servers’ earnings and more than half for bartenders. “When you’re working for tips, you have to please people, and you can’t just throw a drink in some customer’s face because they say something shitty to you,” said Anna Donnell, a six-year veteran of waitressing jobs, primarily in high-end restaurants in Mississippi and Illinois. “A 20 percent tip is how you make your life work.” That makes servers highly dependent on the whims of customers to earn a living. ROC United found that female restaurant workers who live in states where employers can pay them a lower minimum wage if they work for tips are twice as likely to experience sexual harassment as those in the seven states where all workers are paid the same wage.

Servers’ reliance on tips doesn’t only make them vulnerable to harassment from customers; it fuels abuse from co-workers, too. Marie’s first waitressing job was on the night shift at a diner in Massachusetts. In her first month, a cook repeatedly asked her out. “I refused, but in a way where you try to give the soft no and hope that that’s enough.” It wasn’t. One night, the cook asked her for a kiss and Marie said no. He grabbed her by the wrist and dragged her to a prep area behind the kitchen that had a walk-in cooler. He tried to pull her into the cooler while insisting on a kiss. The incident only ended when Marie was able to tear her arm away.

“That was really, really scary,” she recalled. “I told my manager what had happened; she seemed disgusted but not outraged.” Marie had to keep working with the cook, who ended up facing no consequences. “There was no disciplinary process in this restaurant.”

From then on, Marie was subjected to a daily barrage of catcalls, whistles, comments on her body and her dateability, even the spreading of rumors about her sex life. Co-workers grabbed her; one kissed her on the neck. “The cooks would do this thing where they wouldn’t let you take your food to your tables—as you’d reach for the plate, they’d reach for your hand and try to lick [it],” she said. If anyone reported the bad behavior, the cooks would retaliate by purposely messing up their orders. Then “we would lose money from our customers because we’re reliant on the tips,” she said. “You’re not only at the customer’s beck and call…but also everyone around [you] has power over [you].”

Marie couldn’t afford to do anything that might put her job at risk: “You do what you have to do to pay the bills. Are you going to risk getting your hand licked, or are you going to risk getting evicted?” Marie’s dilemma is a common pattern, says Saru Jayaraman, the co-director of ROC United. “Once you’re told to make yourself an object for customers, you’re then an object to everybody in the restaurant.”

Working as a banquet server in a Chicago hotel for 14 years has offered Pavielle steady employment and a way to pay her bills. But she’s dealt with constant harassment from customers. “I was getting pinched, or getting invites,” she said. “Customers grab me at the table around my waist. And I’ve been touched on my butt, I’ve been kissed a lot.” The customers feel entitled to do it: “If I’m waiting on someone, they see me as a servant,” Pavielle observed. “They pay so much money for their tickets [to the hotel’s various events], I guess they just think this is part of the experience.

“It’s almost like it’s part of the job description,” Pavielle continued. “You’re going to get harassed by guests.” Social events, such as weddings or New Year’s Eve parties, are the worst, she added; she’ll often try to call out ahead of those shifts. As New Year’s Eve approaches, Pavielle tries to prepare mentally for the various ways she will likely be harassed.

She also faces another problem that’s pervasive in the restaurant industry: a lack of policies and protocols for dealing with that harassment—and, often, no reliable channel for reporting it. The manager who hired her has also harassed her, so she doesn’t think she can turn to him for help. The other managers, who are mostly male, “don’t see a problem,” Pavielle continued. “They see it as just: The guest is happy—and if the guest is happy, we should be doing whatever we can to keep the guest happy.” As a result, she risks reprisal if she tries to stop the harassment herself. “If I say something to the guest and the guest takes it the wrong way, they could write a bad comment or send an e-mail complaining, and then I could get written up or fired.”

The barrage of harassment is so relentless that Pavielle has almost become inured to it. “It’s like, what’s really wrong?” she said. “It’s kind of hard to tell, because it seems like it’s just so constant, like it’s part of the job.”

Ellen Bravo, director of Family Values @ Work, says that the real problem here isn’t that servers don’t know harassment is wrong; rather, it’s that “nobody’s telling you, ‘You don’t have to put up with that.’ Nobody’s telling you what to do about it. My experience has been that people don’t know what to do.”

Reporting harassment can feel even riskier for immigrant women, those with uncertain citizenship status, and those who don’t speak English as a first language. In the restaurant industry, more than 20 percent of employees are immigrants, including about 10 percent who are undocumented. In the leisure and hospitality industry, which encompasses bars and restaurants, nearly a quarter of employees are Latino.

In the many years that Fabiana Santos and Marta Romero worked at McCormick and Schmick’s in Boston—nearly 14 for Santos, five for Romero—abuse was everywhere, they said. “The sexual harassment was constant and ubiquitous; it was happening every day, all the time,” Santos said in Spanish, speaking through an interpreter. “It was an environment that was tense, dirty, and gross…. There was constant terror and fear.”

“I felt like an object; I felt worthless,” Romero said, also speaking through an interpreter. “And I feel that the fact that I am a Latina woman had a role in this.” At times, men even directed their abuse at Santos’s ethnicity, commenting that Brazilian women are hot and horny.

One time, as Romero was organizing wines in a storeroom, a supervisor came in, trapped her in the room, and groped her breasts—only stopping when another co-worker appeared. One evening when Santos was getting ready to leave after her shift, an employee came up behind her as she was reviewing the schedule and touched her breasts. Both women say there were many other instances in which they were touched by co-workers.

Santos reported these incidents to the general manager and was told they would be addressed, but she says nothing ever happened. Instead, the female workers at the restaurant created “almost like a sisterhood,” exchanging phone numbers and keeping phones close by so they could reach out to one another when they needed to. In 2015, a group of women brought their complaints to the EEOC. The commission recently determined that there was “reasonable cause” to believe that the women had been discriminated against on the basis of their sex, and this past December, Santos and Romero, along with three other Latina women who worked at the restaurant, filed a lawsuit against McCormick & Schmick’s. When asked about the suit, Jeanette McKay, director of legal affairs for McCormick & Schmick’s, gave the following statement: “The Company is not immune from bad actors. Upon notification to the Company’s HR department in 2015, the HR department conducted an immediate investigation nearly 3 years ago and upon conclusion took prompt remedial action, including termination of a dishwasher found to be the main culprit. To suggest that the Company did anything wrong when 3 years ago it immediately investigated the matter and terminated an employee is feeding into the sexual harassment frenzy of today. The lawsuit filed by the attorneys is nothing more than an attempt to make money and it is a shame the media does not see this for what it is.”

Even those food-service establishments where interactions with the customers are more limited, such as fast-food joints, are hotbeds of sexual harassment. Maria says her first experience in fast food will almost certainly be her last. She needed work, and a friend recommended that she apply for a job at a fast-food restaurant. Her first brush with harassment came during training, from the very manager who was introducing her to the job. “He was just standing right behind me,” she said in Spanish through an interpreter. “I could feel he was very close, and I couldn’t concentrate. It was just so distracting.”

Things didn’t change once the job began in earnest. Then another co-worker joined in. “There were many incidents that started right when I started and didn’t stop until I left the job,” Maria said. The two men would make comments about her body or clothing, frequently in front of customers. They kept trying to touch her, despite her attempts to dodge them. When her shift was over, they would try to stop her from leaving, despite her begging and crying.

The constant abuse was emotionally damaging. “I had a lot of fear when I was leaving the store at night,” Maria recalled. “I was afraid that [the manager] might follow me. He has access to information about where I lived.”

Maria wanted to report what was happening to her, but given that her manager was the highest-level supervisor in the restaurant, she had no idea where to turn. “I didn’t know who I could tell or know where I could report it within the company,” she said. Compounding the issue was the fact that she speaks mainly Spanish, which she said meant she had limited knowledge of her rights.

Instead, Maria simply quit her job without another one lined up. “I was tired of the harassment and concerned for my personal safety, and I just couldn’t do it anymore,” she said. But that meant giving up an income that her family relied on. Maria hasn’t worked since; instead, she and her two children have to rely solely on her partner’s wages. She’s clear about one thing, though: “I don’t know what industry I’ll work in, but I’m definitely not working in the fast-food industry.”

Rampant harassment in fast food is due in large part to a young workforce crammed into tight quarters. “There’s a lot of unnecessary and unwanted touching,” says Gillian Thomas, senior staff attorney with the ACLU Women’s Rights Project and former senior trial attorney at the EEOC. When she worked with the EEOC, “We heard a lot of stories about being cornered in the walk-in closet, being locked in the walk-in closet, men exposing themselves…leering, being handsy, rubbing up against people, and it also went all the way to rape.”

The power imbalances in fast food are also stark. For young people, people of color, or immigrants, “fast food might be one of the only places to work, [so] there’s a lot of vulnerability,” Thomas said. “Managers have control over your schedule, have control over how many hours you work, which is how much food you put on the table in the end.” That power imbalance both leads to abuse and makes it difficult for women to speak up about it.

But many of the factors that breed harassment in fast food—tight quarters, fast-paced work, a lack of clear HR protocols, and an anything-goes mentality—are shared by full-service restaurants, as are the experiences of being abused by co-workers who should have your back instead.

When Amy moved out on her own for the first time at age 20, she started working at a family-owned restaurant in small-town Virginia. Serving positions “are really easy to get when you’re young and don’t really have a lot of experience,” she said. “I needed to earn money.”

Shortly after she was hired, she made out with one of the chefs at a holiday party. But she didn’t want it to go any further, and when he asked her out the next day, she turned him down. After she turned him down a few more times, “it morphed into him being really angry about me saying no,” Amy recalled. “Pretty much every day he was taunting me, saying things like, ‘Oh, you think you’re too good for me, you stuck-up bitch’ [and] ‘You think you’re better than me—is that why you don’t want my dick?’

“I just remember going into work every day and knowing that something was going to be said to me,” she added. “It made me just hate going to work.”

This dynamic continued for about a month. Then one day Amy had to get some sauce from a walk-in refrigerator in the back. “He walks in behind me, he shuts the door behind us,” she said, her voice quavering. “I don’t remember [his] exact words, but something to the effect of, ‘You’re going to give me what I want. I’m sick of this—you’re going to get on your knees and you’re going to give me what I want.’”

Amy remembers responding by telling him that she would throw the sauce on him if he did anything to her, and that everyone would know what he had done. “Then he gives me this look of complete disgust, and he’s like, ‘I didn’t want you anyway—I was just kidding,’ and left.”

The incident left her completely unraveled. The harm was compounded by the fact that Amy is a sexual-assault survivor. “I broke down in that fridge,” she recalled. “All of this trauma, all of this everything that I had already experienced—it felt like I couldn’t escape it.” She feared that she wouldn’t be believed if she reported the chef’s behavior, given that people had seen them kissing at the party. “I just remember leaving the fridge and wiping my eyes with my apron…and then going back to work, because what was I going to do?” she said.

Amy worked at the restaurant for a few more weeks, but after the chef kept taunting her, she decided to quit. “I just walked out—I knew I couldn’t keep going into that environment,” she said. But it also meant that she had no income; for the first time in her life, Amy went into credit-card debt. Eventually, she landed a job at another restaurant.

The #MeToo moment has toppled some luminaries of the foodie scene: celebrity chefs like Mario Batali and John Besh, powerful restaurateur Ken Friedman, chef-owner Charlie Hallowell, even Jeremy Tooker, the founder of a San Francisco coffee roaster. But it has yet to permeate workplaces without star chefs, where both customers and fellow servers mete out abuse.

The solutions, however, do exist. An important place to start is recognizing that all of it is illegal in the first place, including harassment from customers. “Under Title VII [of the Civil Rights Act, which makes sexual harassment illegal], it’s very well settled that harassment from any third party is within the employer’s responsibility to remedy,” Thomas said. If an employer knows about, or should have reasonably known about, customer harassment and doesn’t do something to fix it, that employer can be held liable. The EEOC has sued businesses over customer harassment. In 2016, a Costco employee was awarded $250,000 by a federal jury after the commission sued the company for failing to protect her from a customer’s sexual harassment. Recognition of that liability should change the industry culture. “One of the solutions to all of this does have to be a little bit of a reorientation of the restaurant and hospitality culture of ‘The customer is always right,’” Thomas said. Restaurants already have rules about customer behavior when it comes to things like refusing to serve alcohol to someone who’s intoxicated or refusing service to people who aren’t wearing shirts or shoes. “They draw lots of lines,” Thomas pointed out. “One of them has to be that if a customer is harassing a server or other staff members, [it must] be addressed.”

That’s particularly true given that the costs of failing to act can be steep. Defending against legal action is expensive. EEOC commissioner Chai Feldblum wants businesses to know that “the EEOC will be out there, both in terms of outreach and education and in terms of enforcement.” The EEOC can’t independently decide to audit a restaurant or police the industry, but it can act on anonymous reports. If the #MeToo movement spurs more employees to lodge complaints with the commission, “it may be more likely that a restaurant will find the EEOC showing up at their door and potentially suing them,” Feldblum said. Dealing proactively with harassment will be “a lot less expensive…versus the amount of money [you could spend] on lawyers. That should not be a hard cost-benefit analysis for an owner to figure out.”

Jordan Gleason founded the Black Acre Brewing Company, a brewery and taproom in Indianapolis with a clear stance on harassment: “If anybody were to say anything offensive or make servers uncomfortable, they’d be talked to, and if they continued to harass anybody, they’d be kicked out.” His policy was put into practice recently when a customer told a female staffer, “I like staring at your tits.” The customer was asked to stop but didn’t, so the staffer kicked him out.

Gleason believes this zero-tolerance policy pays off. “If someone were to sue you, that’s millions of dollars in liability,” he noted.

Another cost for employers to consider is the price incurred by high turnover as staffers flee an abusive environment. The industry too often views employees as dispensable, so owners allow the harassment to continue under the assumption that unhappy employees can be replaced. But turnover is an economic drain: It costs the equivalent of about a fifth of an employee’s pay to replace her. When Christophe Hille was a partner in a restaurant years ago, a top manager engaged in aggressive abuse and various kinds of demeaning behavior. His restaurant could barely hire fast enough to keep up with the people leaving. Once the manager was removed, the restaurant experienced an “amazing” reduction in turnover. “From that moment…we did not hire a front-of-house position for 18 months,” Hille said. “It proved how directly turnover was correlated with this one person’s actions.”

Some employees are refusing to let harassment in their industry go unchallenged. New Orleans has one of the highest number of bars per capita in the country, and as Caroline Richter has worked in them, she’s also become familiar with the atmosphere of harassment. At one bar and restaurant, a line cook regularly commented on her breasts. But it wasn’t just co-workers: Once, when she ran into a regular customer outside of work, he told her, “I want to fuck you tonight.” Richter tried to laugh it off, but the customer spent the whole night trying to persuade her to go home with him. After she decided to call a cab, the customer followed her outside. “He pushed me against the wall, groped me, and licked me from my collarbone up to my eye,” Richter said. Eventually, she was able to push him off and leave.

When she told her manager about what happened and asked not to serve the customer again or, if she had to, not to be alone behind the bar, “I was told I was being unrealistic and, in asking he be banned from the restaurant, I was just being dramatic,” Richter said. Instead, the manager suggested that the customer be asked to write her a letter of apology. Eventually, the manager agreed to ban the customer from the bar—but he apparently forgot to do so, because when Richter saw the customer a few months later, he tried to hug her hello. “The fact that this wasn’t the first thing on [my manager’s] mind was such an upsetting realization—that other people were taking this so casually,” Richter said. “To me, it was such a huge, life-altering event.”

Richter doesn’t want to put up with the abuse, but she also doesn’t want to leave the industry she loves. So she started a group she’s dubbed Medusa—a reference to the mythical creature with the ability to protect herself by turning men into stone—with two other women from the New Orleans restaurant scene. She found herself thinking, “It’s better to do something and have three people show up to a meeting than just sit around all the time angry and upset about the culture that I’m working in.”

More than three people showed up to Medusa’s first meeting last November: It drew a crowd of about 50, a mix of restaurant owners, front-of-house staff, and back-of-house employees. Richter had to cut the conversation off at 11 pm “because we could have talked for hours.”

She began the meeting by reading a list of guiding principles for the restaurant industry that she created with the help of some psychologists and HR professionals, including a clear zero-tolerance policy and reporting structure for harassment, as well as the expectation that it’s the responsibility of managers to intervene when customers harass the staff. To Richter’s surprise, everyone at the meeting quickly agreed with what she’d drafted. So the discussion shifted to implementation: If they asked restaurants to sign a code of ethics, for example, how could they enforce compliance? How could they make harassment-intervention training standard in the industry?

The organization is now gearing up to create a certification program. Restaurants will pay on a sliding scale, and in return Medusa will offer training about rights, disclosure, and how to intervene when someone is being harassed. After the training, Medusa will certify the establishment. The organization will conduct regular “wellness checks” to ensure that restaurants are complying with its code of conduct, and those that aren’t and fail to make changes will lose their certification. Medusa also wants to serve as a third party where employees can report harassment and be connected with resources. “It’s not you against the entire restaurant; it’s you and all of Medusa against the restaurant,” Richter explained. Their goal is to have a program in place by Mardi Gras.

Other attempts to push a culture change have sprung up across the country. Safe Bars has been training front-of-house staff in the “ways to step up when they see unwanted sexual aggression” directed at both staff and patrons in more than 20 Washington, DC–area bars since 2015, said Lauren Taylor, the group’s founder. She noted that servers are already good at reading whether people are enjoying themselves or not, so “we’re building on their existing skills and expertise.” The trainers offer participants a variety of strategies for intervening with either the abuser or the target. If at least 80 percent of a bar’s staff attends the training, Safe Bars will then certify it, which means the bar can display a window decal and get listed on the organization’s website. The group has trained people in 11 other cities to do similar work in their own locations.

In early January, Futures Without Violence rolled out a training program for a local restaurant association that incorporated small-group workshops about identifying and responding to sexual harassment and role-playing ways to intervene in a harassment scenario set in a steak house. Managers left with information on how to conduct their own trainings in their workplaces. The training is far more involved than just “‘Here’s the complaint procedure, here’s who you report to,’” said Linda A. Seabrook, general counsel at the organization. “A lot of our training programs are pretty intensive because we are trying to do culture change. It’s really more about, ‘OK, if something like this happens, then what are you going to do?’” The organization is currently developing a curriculum for servers, broken down into 10- or 15-minute sessions.

But solutions that emphasize training and cultural shifts depend on owners’ willingness to engage. Advocates are also pursuing public-policy solutions and other organizing efforts that could rapidly reshape the industry. Saru Jayaraman, of ROC United, argues that getting rid of the tipped minimum wage throughout the country would cut sexual harassment in half. “No other industry has a policy solution that goes way beyond education and litigation and regulation,” she points out.

This idea has taken root in a few places. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced last year that he would hold hearings on eliminating the tipped minimum wage in his state. In Michigan, a measure to both raise the minimum wage to $12 an hour and apply it to tipped workers may be on the ballot this November, and activists in Washington, DC, are pushing a ballot measure that would apply the city’s minimum wage to those who earn tips.

Unions can also play a role in enforcing sexual-harassment laws and policies. Historically, harassment hasn’t always been a go-to issue for them. But increasingly, unions representing hotel, restaurant, and casino workers have begun pushing legislative solutions that would mitigate harassment. Unions recently chalked up two major wins in Chicago and Seattle. In Chicago, Unite Here Local 1 helped secure a law that requires hotels to provide a panic button to employees who work alone and also obligates them to draft and comply with an anti-sexual-harassment policy that encourages employees to report harassment and establishes a clear procedure for what happens when they do. Employees must be allowed to stop work and leave the area if they feel unsafe because of a guest, and the law forbids retaliation. With the help of Unite Here Local 8, Seattle passed a similar law via a ballot measure in November 2016.

Ellen Bravo, of Family Values @ Work, says that unionizing is “the most important way for the workers to demand change.” Through the collective-bargaining process, employees can demand that provisions be added to contracts that allow them to stop work and leave a situation if a customer is harassing them. And having somewhere to report harassment other than a manager can be vital. “Knowing that you have a union to back you up—that is enormous, that makes a big difference,” Bravo said. When Melody Rauen started working in hotel bars as a bartender and server, “they put us in skimpy little uniforms,” she said. Guests could easily look down the front of her shirt or up the back of her skirt, and they frequently asked her out or patted her on the butt. But Rauen said that since she became involved with her union, Unite Here Local 8, things have gotten much better. Now she can wear a shirt and slacks, and management “realized that it wasn’t just me saying, ‘Wait a minute’—it was also the fact that I had the union behind me. The union…has really made sure the hotel understands what the repercussions are for mistreating employees.”

Changing “kitchen culture” won’t be easy, says Caroline Richter. “There are people who think the hazing and joking is part of the industry, and if you take it out, [the industry] doesn’t exist anymore.” But if any time is the right time for changing that culture, it is now. “For the past 10, 20, 30 years, the repercussions for speaking out against someone like John Besh was that you got fired and never got hired again.” But the exposé, and Besh’s subsequent departure, “made people feel like this is something we can actually talk about.”

“At the very least,” Richter added, “people who are being affected by the issue aren’t going to forget. And that’s a lot of people.”