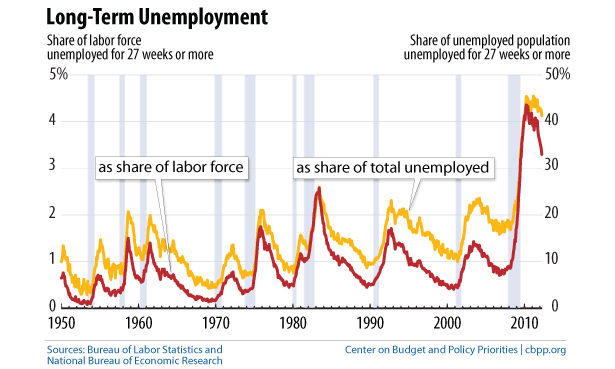

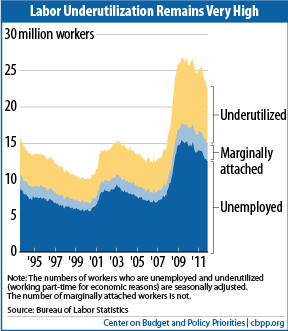

There are 12.5 million unemployed people still seeking work in the United States, and over 5 million of them have been looking for work for twenty-seven weeks or longer.

These are “the long-term unemployed,” and their prospects for finding employment or getting assistance are rapidly diminishing.

The long-term unemployed now make up over 40 percent of all unemployed workers, and 3.3 percent of the labor force. In the past six decades, the previous highs for these figures were 26 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

Instead of helping these folks weather the storm and find ways to re-enter the workforce, our nation is moving in the opposite direction. In fact, this past Sunday, 230,000 people who have been looking for work for over a year lost their unemployment benefits. More than 400,000 people have now lost unemployment insurance (UI) since the beginning of the year as twenty-five high-unemployment states have ended their Extended Benefits (EB) program.

What makes the denial of this lifeline all the more absurd is the reason for it. As Hannah Shaw, research associate at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), writes, “Benefits have ended not because economic conditions have improved, but because they have not significantly deteriorated in the past three years.”

It’s all about an obscure rule called “the three-year lookback.”

Under federal guidelines, for a state to offer additional weeks of benefits it must have an unemployment rate of at least 6.5 percent, and—according to the lookback rule—the rate must be “at least 10 percent higher than it was any of the three prior years.”

“Unemployment rates have remained so elevated for so long that most states no longer meet this latter criterion,” writes Shaw. She points to California as a prime example. For more than three years, its unemployment rate has remained above 10 percent, but it fails the three-year lookback test because the rate didn’t rise sufficiently. As a result, over 90,000 Californians lost their benefits on Sunday.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Prior to Congress reducing the maximum number of weeks of unemployment benefits earlier this year, there was some discussion of changing the lookback rule to four years, or even suspending it. But in the end there wasn’t the political will to do it and there certainly isn’t now.

Shaw wants people to understand the real impact that these cuts have on the long-term unemployed.

“Many of these people have been looking for work for well over a year and now their UI benefits have ended sooner than expected,” she says. “Many families rely on these benefits to make ends meet [and now] many are left with little else.”

Indeed in 2010, unemployment benefits kept 3.2 million people above the poverty line—which is roughly $17, 300 for a family of three. A report from the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) gives some indication of what might lie ahead for people who exhaust their benefits.

Of the 15.4 million workers who lost jobs from 2007 to 2009, half received unemployment benefits, half didn’t, and about 2 million who did receive benefits exhausted them by early 2010. Those who exhausted benefits had a poverty rate of 18 percent, compared to 13 percent among working-age adults; more than 40 percent had incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty line (below about $35,000 for a family of three), which is the level where many economists believe people start really struggling to pay for the basics.

Of the 15.4 million workers who lost jobs from 2007 to 2009, half received unemployment benefits, half didn’t, and about 2 million who did receive benefits exhausted them by early 2010. Those who exhausted benefits had a poverty rate of 18 percent, compared to 13 percent among working-age adults; more than 40 percent had incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty line (below about $35,000 for a family of three), which is the level where many economists believe people start really struggling to pay for the basics.

While one might expect to see budgetary savings from reduced unemployment insurance payments, anti-poverty advocates say a shift in demand is more likely, as more people—especially families with children—turn to other safety net programs like food stamps, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Assistance will be much harder to come by for individuals or couples without children, especially since state General Assistance programs have been decimated.

It is all the more alarming—as National Employment Law Project executive director Christine Owens testified in Congress this week—that older workers ages 50 and up are disproportionately represented in the ranks of the long-term unemployed. They made up over 29 percent of long-term unemployed workers in 2011, compared to just 26 percent in 2007. In 2011, more than 54 percent of older jobless workers were out of work for at least six months, and those high rates have continued into 2012. Owens noted that prolonged periods of unemployment can have a severe impact on older workers’ retirement prospects and later-life well-being.

In addition to legislation protecting older workers from discrimination, Owens urged Congress to invest in subsidized employment and workforce development and job training programs—vital to unemployed workers of all ages.

According to the Center for Law and Social Policy, a 2005 study of seven states found that adults and dislocated workers receiving Workforce Investment Act (WIA) services—including job training—were 10 percentage points more likely to be employed and to have higher earnings (about $800 per quarter in 2000 dollars) than those who hadn’t received services. They were also less likely to need public assistance. A 2011 study by Washington State found that WIA services boost employment and earnings for adults, dislocated workers and youth.

House Republicans are attempting to “reform” federal workforce programs through the positively Orwellian-named “Workforce Investment Improvement Act.” When they say reform, they mean pulling out their handy-dandy, favorite tool: the block grant.

“Basically, the legislation would throw funding that currently is used for specialized training programs into one big pot—and reduce the amount of money in that pot,” says Shaw.

It’s true that job-training programs need improvement but simply cutting funding and eliminating programs won’t do a thing to help anyone. What is needed is a serious effort along the lines of what economists Dean Baker of the progressive Center for Economic and Policy Research, and Kevin Hassett of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, describe in a New York Times op-ed:

Policy makers must come together and recognize that this is an emergency, and fashion a comprehensive re-employment policy that addresses the specific needs of the long-term unemployed. A policy package…should spend money to help expand public and private training programs with proven track records; expand entrepreneurial opportunities by increasing access to small-business financing; reduce government hurdles to the formation of new businesses; and explore subsidies for private employers who hire the long-term unemployed.… Managers who are filling open [government] positions should be given explicit incentives to reconnect these lost workers.

If there isn’t enough urgency for legislators and their constituents already, people should consider this: things are about to get worse. Not only did Congress fail to address the lookback earlier this year, it also made changes that will shorten the number of weeks people can receive temporary, federally funded benefits after exhausting their state-run programs. Those reductions will begin at the end of this month.

“It’s not going to be as dramatic as the end of the Extended Benefits program—there won’t be hundreds of thousands of people losing their benefits all at once,” says Shaw. “But the changes are coming down the pipeline and will affect people in every state. The UI program will look very different in a few months than it does today.”

So Rich, So Poor by Peter Edelman

When it comes to public policy and poverty in the United States, few people know more about it than Georgetown University law professor Peter Edelman. He has battled poverty for nearly fifty years, most notably as a legislative assistant to Senator Robert Kennedy and as an assistant secretary of health and human services in the Clinton administration—a post he resigned in protest over the 1996 welfare reform bill. He’s taught and written extensively on the subject, too, including his new book, So Rich, So Poor: Why It’s So Hard to End Poverty in America.

Full disclosure: Edelman is a friend of mine and a mentor when it comes to anti-poverty work. I also had the opportunity to advise him on this book. Still, I wouldn’t be writing this if I didn’t value the book, nor would he want me to.

So Rich, So Poor is a sweeping historical account and analysis of anti-poverty policy that will give readers a sense of where this nation has been—and where it’s headed—with regard to confronting (or failing to confront) poverty. Edelman examines the challenges of concentrated and intergenerational poverty, the safety net, the plight of those in deep poverty, disconnected youth, low-wage work, race and gender issues, housing policy and much, much more.

If you are a layperson, the book is a chance to absorb more than you probably ever realized is at the heart of the fight against poverty; if you are someone who has long been involved in the fight against poverty, I have little doubt you will find new ideas, angles or inspiration in these pages.

This is a man who has devoted a lifetime to fighting poverty and is passing along what he’s learned. It’s a gift, frankly.

I had an opportunity to speak with him about the book and his perspective on poverty. This is what he had to say:

Greg Kaufmann: What do you hope readers get out of your book?

Peter Edelman: I hope to reach a broad audience of people who don’t know a lot about why so many people are poor in this country. I want people to understand that we’ve done a lot of things that have worked in reducing poverty, but also to understand why we still have so much poverty.

What do you say to people who respond that the reason we have so much poverty is that these programs don’t work and they are a waste of money?

The programs do work, and about 40 million more people would be poor if we didn’t have them. The problem is that we have so much low-wage work and too many people who are coping as single parents trying to live on income from one low-paying job. A second problem is that we have so many people who have incomes below half the poverty line—who are in deep poverty—and we are doing very little to help them. Since 2000 we’ve seen a rise in the number of people living in deep poverty from 12.6 million people to 20.5 million—they are living on incomes of less than about $11,000 annually for a family of four. And then we have the even more challenging problem of persistent and intergenerational poverty.

Can you say a little more about how that’s a different kind of problem to address?

Most people who are in poverty or deep poverty go in and out of those categories. But among those who are very poor, and others who remain poor for long periods of time—especially people who live in places where there is a lot of concentrated poverty—many of them have personal problems, and there’s a lot more of the consequences of inadequate education and a lack of jobs. So that whether it’s in an inner-city, or Appalachia, or on Indian reservations, or in the Mississippi Delta, we have places of poverty in this country that are even more challenging in terms of what we need to do.

What are some of the least talked-about aspects of poverty today?

The poverty problem in this country is, on the one hand, more a problem for white people than any other group; and on the other hand, it’s a problem that’s very much connected to race, and we need people to understand both sides of that.

The largest number of people in this country who are poor are white—they are the largest group. It’s also true that African-Americans, Latinos and Native Americans are poor at a rate that’s nearly three times the rate of poverty among whites. Why is that? It reflects continuing issues of race and gender. There’s disproportionate poverty among people of color because of history, continuing discrimination, structural racism in the way that our schooling is arranged for children, and the way our criminal justice system operates, and in residential patterns.

The American reaction to poverty tends to be a reflexive image of a person of color, and that in turn—because of the way our politics are structured—hurts the case for taking action. So we need to put race and gender on the table as part of the discussion.

Looking at the breadth and depth of the challenges involved in the fight against poverty, do you feel hopeful that we can rise and respond to them?

We know much more than we did at the time of the Great Society about what works, so that’s a good thing. But we do need much more political will, and we need more public understanding that these are problems that can be solved. We can help people get more income from work, we can have a better safety net, we can do a much better job of educating our children.

Some of the problems are very difficult, that’s for sure, but I think the biggest issue is for people to understand that it’s in our self-interest as a country to act. Not just because it’s morally right—although it is—but because an economy that includes everybody is going to be a better economy for everybody. It pays off economically for the whole country, not just for the people whose personal quality of life is improved. It costs us a huge amount of money in terms of lost productivity, crime-related costs and increased costs of healthcare not to act. One estimate is that we are losing at least $500 billion per year just due to the costs of child poverty.

What is the importance of the book coming out at this particular moment?

I hope that the book does some good in the context of the current election campaign—that people will want to discuss the question of inequality not just at the top, not just the 1 percent, but also the 99 percent all the way down to the bottom. The table has been set by the Occupy Movement for a national discussion of inequality that includes the reasons why people are hurting so much at the bottom as well as why some people have so much at the top. We need to talk about poverty. The p-word needs to be in the discussion.

The Economic Hardship Reporting Project

Best-selling investigative journalist Barbara Ehrenreich and the Institute for Policy Studies have launched the Economic Hardship Reporting Project to help move the crisis of poverty and economic insecurity to the center of the national conversation.

The Project aims to let unemployed, underemployed and those whose employment situations are tenuous know that they are not alone, that the current economic crisis is not their fault and that they are not always getting the information they need to find solutions. Through innovative journalism on poverty and economic hardship, reporters will tell compelling stories of individuals and families that are linked to the bigger picture—exploring extreme inequality and the decline of the middle class.

Significantly, the Project is inspired in part by the Depression-era Federal Writers Project and is collaborating with several unemployed or underemployed journalists. Freelancing is a tough road, especially right now. In recent months I’ve heard from talented reporters who have had to turn to the safety net themselves. I’ve spoken with highly accomplished journalists—whose names many of you would know—who have been asked by major media outlets to write for free just to keep their names out there (and because the outlets know they can get away with it).

“I am impatient with the standard liberal discourse on poverty,” said Ehrenreich. “We can’t go on talking about poverty without talking about how it’s being manufactured and intensified all the time.”

Ehrenreich launched the Project this week with her article, “Preying on the Poor.” I’m proud to be one of a number of advisers involved with this important effort and I hope you will follow and support it.

Video: “Still Face Experiment”

Much has been written in recent years about the link between “toxic stress” in young children and their educational, health and social outcomes later in life, as well as the public policy implications when it comes to addressing poverty. The brain is extremely pliable in the prenatal and early years, and brain architecture can be changed for the better or worse during this window. It then becomes increasingly difficult to modify over time.

For an incredible demonstration of the impact of stress on a baby—and this stress isn’t even all that toxic and lasts less than a minute—check out this video from ZERO TO THREE, a nonprofit organization working to improve the lives of infants and toddlers.

Jodie Levin-Epstein, deputy director of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP), reacted to the video this way: “From CLASP’s perspective, this video shows the fall-out from the time-poverty of parents. Fully 40 percent of working low-income parents (below 200 percent of the poverty line) have no paid time off of any kind—no parental leave, no vacation, no sick days. This is a no-brainer to fix. The US should join virtually every other nation on the globe and provide paid leave for parents. So far, the presidential candidates have not addressed this issue head-on. It’s time. And then we need to ensure good early child care.”

Get Involved

Put Childcare on the Map. Currently only about one in six children that qualify for federal child care assistance actually receives it, and it’s not on the minds of too many members of Congress. Make sure they understand just how urgent quality, affordable child care is for working families. RESULTS, the National Women’s Law Center and the Early Care and Education Consortium have launched this new long-term campaign to put child care on the map.

Raise New York’s Minimum Wage. Good news for New Yorkers: the Assembly has voted to raise the state’s minimum wage to $8.50 and index it to inflation. But Governor Andrew Cuomo has not committed to the bill, nor has he urged the Senate to pass it. The National Employment Law Project notes that the wage would be over $10.50 today if it had maintained its value since 1970. The current wage is $7.25 an hour so a full-time worker earns $15,080 annually.

“Poverty wages are good for Walmart and McDonald’s, but they’re not good for New York,” said Dan Cantor, executive director of the Working Families Party. New Yorkers can urge Governor Cuomo and Albany to take action here.

Hold the House Accountable. Last week I wrote about the cuts to “lower-priority spending” that House Republicans voted for in order to protect defense spending and tax cuts for the wealthy. The bill would slash food stamps, Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act, the Child Tax Credit, the Social Services Block Grant and other programs poor people rely on at a time of record poverty. In an email, the Coalition on Human Needs (CHN) writes, “The people who want to protect or increase military spending and tax breaks at the top are making their views known, day after day. We cannot be silent.” CHN is giving you the opportunity to express your displeasure or approval with your Representative’s vote here. The only way they will know we care about poverty is if we start telling them we care about poverty.

Save the American Community Survey. The House voted last week to eliminate funding for the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. It’s the only source of objective and comprehensive information about the nation’s social, economic, and demographic characteristics down to the neighborhood level. The information is used by the public, private and nonprofit sectors for everything from funding programs and assessing their effectiveness to enforcing the Voting Rights Act to delivering goods and services. You can find your Senator and tell him or her to save the American Community Survey here.

Notable Studies

“Welfare Reform: What Have We Learned in Fifteen Years?” Urban Institute & MDRC. Fifteen years after the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program replaced America’s longstanding cash-assistance entitlement, eight briefs by the Urban Institute and MDRC assess how well TANF works within the larger social safety net and to what extent it helps families receiving aid toward self-sufficiency.

“Policy Matters: Public Policy, Paid Leave for New Parents, and Economic Security for US Workers,” the Center for Women and Work at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey and the National Partnership for Women & Families. The report shows how paid leave policies can be viewed as proactive public investments in the health and well-being of children and families in the United States. Also, public assistance and food stamp receipt are lower for new mothers who live in states with paid leave policies.

Further Reading

“A Mom Struggles as Budget Crisis Deepens,” Dan Morain

“WPB Neighborhood Concerned About Trash and Transients,” Dan Corcoran

“The Human Disaster of Unemployment,” Dean Baker and Kevin Hassett

“Social Justice Movements in a Liminal Age,” Deepak Bhargava

“The Outlook is Still Grim for Women in the Job Market,” Bryce Covert

“For Mother’s Day: A Present that Values Families,” Hannah Matthews & Jodie Levin-Epstein

“An Alarming Number of Americans Think Poor People Are Simply Lazy,” Mandi Woodruff

“Community Struggles With Poverty Rate Twice National Average,” Spencer Platt

“Hunger Among Senior Citizens Continues to Rise,” Alfred Lubrano

“Recession Added Debt, Drained Families’ Savings,” Christine Dugas

Vital Statistics

US poverty (less than $22,314 for a family of four): 46 million people, 15.1 percent of population.

Children in poverty: 16.4 million, 22 percent of all children, including 40 percent of African-American children and 37 percent of Latino children.

Number of poor children receiving cash aid: one in five.

Poverty rate for people in female-headed families: 42 percent.

Poverty rate for children under age 5 in female-headed families: 59 percent.

Single mothers with incomes under $25,000: 50 percent.

Single mothers working: 67 percent.

Deep poverty (less than $11,157 for a family of four): 20.5 million people, 6.7 percent of population. Up from 12.6 million in 2000.

Increase in deep poverty, 1976–2010: doubled—3.3 percent of population to 6.7 percent.

Twice the poverty level (less than $44,628 for a family of four): 103 million people, roughly 1 in 3 Americans.

Families receiving cash assistance, 1996: 68 of every 100 families with children living in poverty.

Families receiving cash assistance, 2010: 27 of every 100 families with children living in poverty.

Impact of public policy, 2010: without government assistance, poverty would have been twice as high—nearly 30 percent of population.

Quote of the Week

“People want to say people on welfare are sitting around. I’ve been hustling. I’ve been begging. I’m on my knees. I cry every day. My daughter doesn’t deserve this.”

—Jonetta Hall, single mother of 4-year-old Kayla

This Week in Poverty posts every Friday morning. Please comment below. You can also e-mail me at [email protected] and follow me on Twitter.