Walking the Camino in the Shadow of Belief

I trudged through Spain as a rift grew within American Catholicism. I returned home with a renewed sense and understanding of faith.

A pilgrim approaches the church in the village of Hospital on the Camino de Santiago.

(Xurxo Lobato / Getty Images)

It began with the reckless flip of a coin. Heads, tails. Right, left. Forwards, backwards. “Fate,” or something stranger.

Standing on a sidewalk in Brooklyn beside a man who did not love me but who would not let me leave, I liked to play a game, one borrowed from the Situationists in Paris. I liked to take long walks. Upon reaching an intersection, I’d take a quarter from my pocket kept expressly for these purposes and flip it. Heads, we’d take a right. Tails, left.

Sometimes I’d adjust the rules: Tails would embolden me to walk backward a block while heads meant I would move forward. It kept the uneasy air between me and this man calm, lending a sense of purpose to the otherwise aimless hours we spent together, building toward nothing. With these simple goals, we were distracted, and we would not argue. I could convince myself that he was kind.

One afternoon, after I took myself out on one of these walking games, this time alone, I fantasized about what it might feel like to walk endlessly; to walk out of my day-to-day life and into a happier future. To walk for hours, long past the time I usually spent on these meanders. I was in graduate school, with a student’s schedule for the first time in over a decade, and I’d have the summer off.

A few days later, a photo taken by a stranger in Spain came up on my timeline. It depicted a stretch of something I had once heard of, back in my days of Catholic school: the Camino de Santiago. An ancient pilgrimage dating from the ninth century CE, crisscrossing Spain and ending at the cathedral of the northwestern city of Santiago de Compostela, where the remains of the apostle James supposedly lie, in the last 40 years transformed into a popular and somewhat secularized revival following an enterprising Galician priest’s idea to renovate the trails as a tourist draw.

I turned the quarter over in my palm. Heads, tails. Forward, or backward?

Often, when you toss a coin in the air so as to allow Providence to make its decision, you already know which path you’re going to take.

Of all the various forms of long-distance walking that can be found—the hike, the urban ramble of the flaneur—the pilgrimage is perhaps the truest distillation of one of the principal aims of this kind of walking: that of losing oneself.

The Camino de Santiago, or the Way of Saint James, is in fact not simply a single path but many, crisscrossing across Spain and connecting the other pilgrim paths found across Europe, each ultimately leading to the shrine of Saint James located in Santiago de Compostela.

During the late Middle Ages, the Camino became especially popular. Saint Francis of Assisi is one of the many pilgrims said to have walked its path. The particular Camino that I chose to follow—colloquially known as the Camino Frances, or French Way, since it starts at the base of the Pyrenees, the border between France and Spain—is the most famous of all the Caminos. Walking, on average, six to seven hours and 30 kilometers a day, I passed from the south of France into the north of Spain, walking westward through cities that included Pamplona, Logroño, Burgos, and Ponferrada, along with numerous small towns and villages. I hiked mountains, navigated through wet forests, and crossed flat and dusty plains. In total, it took me roughly five weeks to complete.

My decision to walk the Camino was not rational. Days after I first saw the photo of it online, I had booked myself a plane ticket and bought a guidebook, my actions more the result of a of gut-level compulsion than an orchestrated plan. I spoke almost no Spanish. I was heartbroken, didn’t have much money, and every editor in New York was passing on both a novel and a short story collection I had written. What I craved most was a blankness of the mind, a stripping away of myself and my identity, which would allow me to bypass the anxious spiraling that had left me frozen in place as I awaited the decisions of others. The pursuit of chance and serendipity, like the kind offered by coin flips and the Situationist dérive, or unplanned drifting through an urban landscape, struck me as one way to achieve this state of being. But so too was this idea of ceaseless walking, mindless walking, the kind of walking that would—I hoped—offer its own form of transcendence, not dissimilar to that of which experienced by the mystics and the saints whose existence had formed a vague and constant wallpaper to my life since childhood.

Quickly, I came up with a plan, finding someone to sublet my room in Brooklyn and arranging to briefly cat-sit for a friend in Paris before finally taking a train down to the Camino Frances’s traditional starting point, a small and winsome French town called Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. I did not practice or train much, naïvely thinking that all my city walks would be enough to prepare me. This would quickly prove to be untrue: On the first three days of the Camino alone, I’d lose multiple toenails.

There was another reason I felt compelled to walk, though; one that was more difficult to articulate. I could think of it only as a loss of rhythm, and it was why I, who was as lapsed as a lapsed Catholic could be, found myself drawn to the idea of a pilgrimage. I had been raised a Catholic, but I had dropped out of my confirmation class the week before I was due to be confirmed after picking a fight with the teacher about abortion rights (my mother had been proud of me), and had not attended Mass since my father’s death a few years after that, when I was 16. Having been born at the tail end of the 20th century, I lacked any desire for belief. I had never had a holy experience in my life. And yet, for my entire childhood, the rhythm of belief had defined my calendar, it was the incongruent metronome by which we had paced our lives. In its absence, something about my own internal clock had gone haywire.

This rhythm still imposed itself upon me, articulated itself subtly within the rhythms of my life, the memory of it, the grooves of it, it had fitted itself against my very musculature, my skeleton—from a young age it had been cultivated, we fit together, and though I tried it seemed that I could not excise it fully. I could not cut it away—it would always be there, it would remain tap-tapping a rhythm, distinct and heard only by me, against the interior of my skull.

Around this time—it was 2023—a rift continued to grow inside the American wing of the Catholic Church. This had been underway for years, ever since enterprising conservatives had used the passing of Roe v. Wade as a means to mobilize and win over historically Democratic Catholic voters. More recently, a semi-ironic vogue for converting to Catholicism had spread across members of both the right and the left. Often, these newcomers espoused a distaste for certain developments in the Church’s recent history—a vocal dislike, say, for some of the reforms associated with Vatican II, including those that led to Masses being held in the respective colloquial languages of the church’s peoples, rather than the traditional Latin Mass—that caused confusion for people like my mother, who had in fact grown up with and hated the Latin Mass. Wasn’t it better, after all, to be able to understand what the priest was saying?

There was something oddly mannered and self-satisfied in the way that someone like JD Vance spoke of faith. A shamelessness suffused him, and the politics he espoused—the distrust towards immigrants, the nationalistic tribalism—would later, in 2025, lead to a public argument between Vance and several Catholic bishops in the United States. There is a basic contradiction to the Catholic Church. For all the moneyed excess and bad politics displayed by the Vatican over the centuries, there exists also inside Catholicism a twinned longing for charity, for mercy, and for transcendence. A long tradition of mysticism exists within the faith, often serving as an opportunity for the increased participation of women, who remain barred from the clergy. For myself, whenever I thought about the question of faith, a certain image repeated itself in my mind: that of my head bending towards a wall, a floor. And bashing my forehead forward until it began to bleed.

One might deny an interest in belief, but on the Camino, belief has a way of finding you.

To even begin this journey is to step outside of order, and into a more diffuse approach to time and space. Though there are maps, they do not always lead you anywhere; more reliable are the yellow arrows marking the way, some spray-painted and others embedded, via tiles, into sidewalks. But these, too, can be uncertain. Shells are also important symbols, appearing on various markers and taken from a sideways glance of how the various Caminos, upon converging at Santiago, look like a shell. When beginning their walk, every pilgrim receives a shell to tie to their backpack, marking us. Laws dating back to the Middle Ages protect the pilgrims—there are special fines, for instance, for hurting or robbing pilgrims.

There were moments as I walked in which it felt as though time moved differently. Early on, as I sat resting on a tree stump, I felt a prickling sensation at the base of my neck, and understood, somehow—with no evidence—that there was someone in the woods watching me. A circle of expensive-looking-attired men and women on horseback gathered around myself and another woman one day, like aristocrats of yore, excitedly exclaiming in Castilian Spanish about the peregrinos—pilgrims, made obvious by our walking poles, hiking shoes, seashells, and tired expressions—they had found.

In Pamplona, witnessing the Running of the Bulls, I watched the city as it was possessed by an overwhelming and frenzied energy that tapped into a tradition obscure and bloody. In an albergue—the hostels that pilgrims stay in—run by nuns in the desert portion of the Way, the sisters led us in singing a pilgrims’ song dating back to the Middle Ages. I found myself crying hot and unexpected tears. That night, a French priest who had kindly offered me almonds in Pamplona presided over the first Mass I attended in over 15 years. Kneeling and rising again in the pew, I felt unsteady, like a knock-kneed foal unsure of how to walk and yet following the body’s memory.

Luck, too, had a way of finding me at my lowest: Toward the end of the Camino, when I had one final mountain to climb and all I wanted to do was go back to Brooklyn, relief came in the form of an unexpected kindness: an Irish pilgrim had paid it forward at a very nice albergue, allowing anyone traveling on an Irish passport—this happened to include me—to spend the night for free.

What was it that I was after, other than a novel challenge that would put me outside of myself and allow me to ignore and avoid the anxieties I had left in the United States? The first 10 days of the Camino were some of the hardest of my life. Standing at the top of yet another hill in an endless rolling series of them, I began to cry uncontrollably. I had imagined the Camino as a form of escapism; what it offered instead was a confrontation. Another rejection had landed in my inbox as I climbed that hill, and my mind circled endlessly around what had led me to begin this walk. My feet bled, my right shoulder hurt, and nothing was going according to plan in either my romantic or my professional life.

Since childhood, I had exhibited a relentless and rigid need to plan, to chart my life out, to make sure I was hitting my goals. On the Camino, there was no plan. Each day moved differently; not one looked similar to the days before. I was alone on that hill, and I had no coin to flip. A cliché popped into my head, albeit a bit of a truism: I would have to accept that there were things in life I could not control. Self-pity would accomplish nothing; it would instead detract from the real goal at hand, which was experience. Immediately, I stopped crying.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Two years after I walked the Camino, an American became the pope. This was a choice that, outside of television shows, seemed for years unlikely, simply due to the United States’ place as the world’s leading hegemony. To have the leader of the world’s most powerful country share a nationality with the leader of the world’s largest Christian denomination seemed too much.

Livestreaming the news surrounding the papal conclave, I listened to two BBC reporters speculate that if, by some chance, an American were chosen, it would be a sign indicating the US’s diminished global position—as well as a warning to those hard-liners who were, such as the vice president, against Vatican II and in favor of repressive crackdowns on immigrants, refugees, and the poor.

It is both our fortune and our misfortune that we live—still—in an age of belief. Perhaps this is not always belief in religion. But there is belief in certain political ideologies; belief in certain speeches; belief that the ugly ideas of the past, its fascisms and its prejudices, hold the key towards creating a new future. But amid all this smallness, belief also holds the capacity for something bigger, something truer. Belief is what I feel when I read a novel and know that human hands made it, that a human mind is speaking directly to me, not the pale imitation set forth by AI. Belief is what I feel when I set one foot in front of the other before I begin a long Saturday morning walk, having left my phone at home so as to not distract me from the world outside. Belief is what hovers in the air in that exact breath-caught moment in which the coin is turning and turning, the future still unknown.

Upon reaching Santiago, the end of every Camino route, I felt a kind of momentary emptiness. After five weeks of walking, to have reached my destination meant that an end I was not ready for was drawing nearer. Numb, I collected my certificate of completion issued by the Archdiocese of Santiago de Compostela and dropped my bag off at a small private albergue room I had rented for the night, before attending that day’s pilgrim’s Mass alongside new friends with whom I had been walking the last few weeks. Sitting inside the vast and glittering cathedral and smelling the richness of the incense—a smell that always reminded me of the first day of school in the suburbs of Seattle, when the priest would bless us as we stood lined up before class—I began, suddenly, to break down.

A woman’s arms darted out to grip me. I hadn’t noticed her sitting beside me, and if she was a pilgrim, she had to have started walking later than the group of us who had been walking since France, because I didn’t recognize her. But there was something immensely comforting to this stranger’s arms around me, holding me up so that I didn’t fall. Without speaking, she soothed me, holding me close to her and allowing me to cry. When the service was over, I wiped some of the tears and snot from my face clumsily and thanked her.

She said nothing. She simply smiled a small half-smile and gave me another big hug before slipping something into the palm of my hand. I looked down at it, felt the grooves of it. Not a coin, but a shell. Like a smaller version of the pilgrim shell I wore tied to the zipper of my backpack.

“Thank you so much,” I tried to say. But when I looked up, she was gone.

More from The Nation

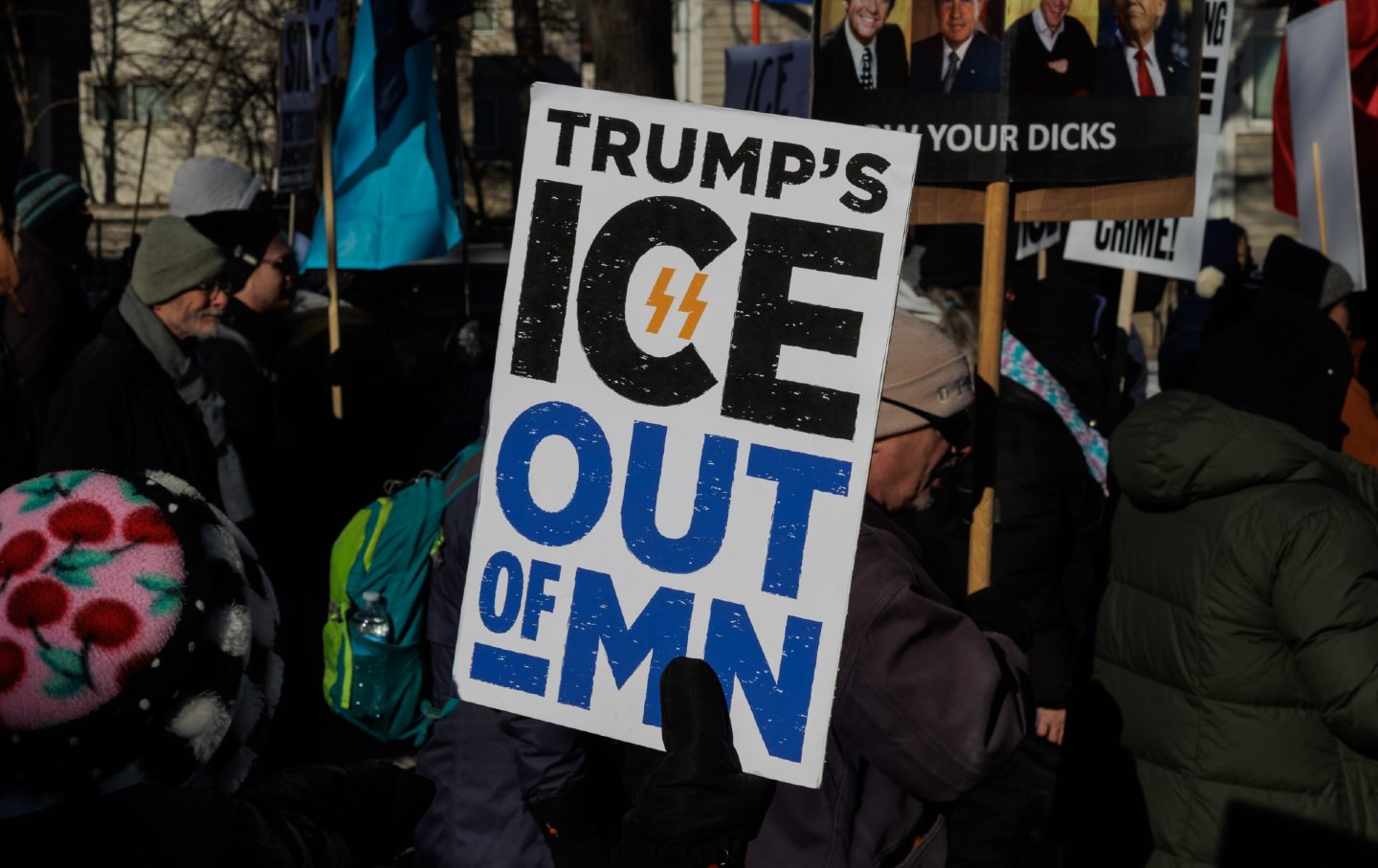

ICE Melts in the Minneapolis Winter ICE Melts in the Minneapolis Winter

Now it’s time to abolish the agency and impeach Kristi Noem.

Minnesota Made Trump Blink Minnesota Made Trump Blink

But Tom Homan is a lying liar, and the work’s not done. Plus, Gallup’s sketchy new polling policy (is the analytics firm in the Trump tank?), the law for deepfakes, and more in th...

The Republican Crack-Up Has Begun The Republican Crack-Up Has Begun

Even conservatives are fleeing the GOP as more and more Americans turn against Trump’s authoritarian project.

The NFL Owners and Olympic Organizers in Epstein’s Inbox The NFL Owners and Olympic Organizers in Epstein’s Inbox

The sports media is ignoring the story, but wealthy sports figures are all over the Epstein files.