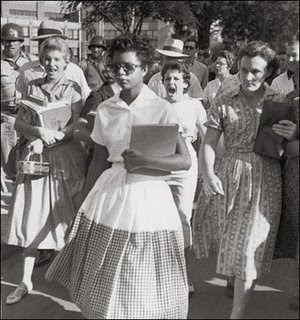

One of the most enduring images of the Civil Rights Movement is of Elizabeth Eckford. She is being harassed and taunted by a group of white students, parents, and police on her way to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. On that morning Eckford missed connecting with the eight other African American students of the Little Rock Nine and their NAACP leader, Daisy Bates. Eckford was alone when the angry crowd surrounded and confronted her.

The photo is now iconic. Eckford’s dignity, strength, and self-possession are stunning counterpoint to the contorted, hate-filled faces of those following her.

This image of Eckford kept returning to me as I watched the Senate confirmation hearings of Sonia Sotomayor. Although Sotomayor herself deplores metaphor and analogy, Eckford’s harassment seemed an apt comparison to the hearings. Although her confirmation was nearly certain, Republican senators were determined to make Sotomayor walk a gauntlet on her way to the Supreme Court.

After Anita Hill’s testimony, Clarence Thomas famously called his confirmation hearings a "high-tech lynching." Yes, he was a powerful black man subjected to white interrogation about sex, but it was a terrible analogy because no group of white men has ever formed a posse to lynch a black man in defense of a sexually degraded black woman. The lynching imagery was powerful nonetheless and Thomas forcefully deployed it against the senators. It framed a particular, historic understanding of black men’s vulnerability within white-dominated systems of power. Women of color have fewer metaphors available to contextualize their degradation and dehumanization. For me the Sotomayor hearings were an Elizabeth Eckford moment.

Like Eckford, Sotomayor has been praised for her dignity, her stillness, and the evenness of her voice as she responded to hostile mischaracterizations. She managed to laugh off sexist jokes. She didn’t flinch when she was repeatedly interrupted. Senator Lindsey Graham warned that her confirmation could only be derailed if she had "a complete meltdown." The rules of the game were set: the Senators could mischaracterize her record, accuse her of racial bias, and mispronounce her name but she could not respond in kind. She could not be hurt or offended or angry. She had to remain a pillar of rationality and neutrality and control.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The hearing was a performance of a broader set of social rules that govern race and gender interactions in American politics. Women, and most especially black and brown women, have to prove their fitness for public life by demonstrating the ability to endure harsh brutality without openly fighting back. The ability to bear up under public degradation is a test of worth. America’s favorite black woman heroine is Rosa Parks, a woman who is remembered as silently enduring the humiliation of being ejected from a public bus for refusing to comply with segregated seating.

Sotomayor passed the test. She met the Senators’ questioning with thoughtful responses. Her voice did not quiver. Her face did not scowl. Many women of all races feel inspired by her. But I wonder about this lesson that continues to teach women that we can only have space in the public realm as long as we control all emotion.

Undoubtedly part of the power of the non-violent Civil Rights Movement was its ability to reveal the evil of segregation by displaying the segregationist’s disproportionate response to upstanding citizens. Yet one of the reasons black power emerged from the rubble of the Civil Rights Movement was to fulfill another basic human need: the desire for self- defense when attacked.

All Supreme Court nominees endure tough, ideologically driven questioning. It’s as true for white male conservative justices as for Sotomayor. But this public display took on different meaning as white men repeatedly asserted that Sotomayor was capable of making legal judgments based only on her personal experience and ethnic identity.

I was proud of Sotomayor’s restraint, but I also wanted her to counter attack, to punch back, to show anger. She couldn’t do so in part because she is bound by the rules of judicial decorum. She also couldn’t do so because of the racialized, gender rules of political engagement that allow white men, from senators to firemen, to express outrage, indignation, and emotion, but disallow those same expressions from women of color.

Such restraint comes at a cost. Elizabeth Eckford must have been terrified and hurt behind those dark shades, but she never shows it. Sotomayor must have been angry at times this week, but it never showed. They are each powerful trailblazers whose dignified response is estimable. They are also morality tales that suggest women still have little room for public displays of emotional self-defense.

The Republican attacks on Sotomayor were not meant to derail her nomination. They were meant to degrade and humiliate as a warning: if you attempt to assert your equality within a system still dominated by white male racial privilege you may get a place at the table, but not without public punishment.