One of President Donald Trump’s closest friends and confidants took advantage of the Great Recession to build an unprecedented real-estate business that makes him tantamount to a modern-day slumlord—buying up homes, hiking rents, and allowing the properties to fall into disrepair. Southern California billionaire Thomas J. Barrack is the mastermind behind the scheme. Five years ago, Barrack founded a company now called Colony Starwood Homes. The company has subsequently removed 31,000 single-family homes from the US housing market and transformed them into high-cost rentals. Barrack calls it “the greatest thing I’ve ever done.” Like other Trump associates, he now stands to profit further from looser financial regulations, which he is in a position to shape through his influence with the president.

“We’re just little people in his world,” Makita Edwards, 25, says of Barrack, whose company owns the split-level neocolonial she rents in Atlanta’s eastern suburbs. Since Edwards and her family moved in last August, she says her life has been a nightmare. They went without heat in the winter and dealt with persistent water leaks. Two weeks after moving in, Edwards was lying in bed with her 3-month-old son, Mason, when the ceiling caved in and the ceiling fan collapsed on top of them. Luckily, no one was hurt.

“It’s kind of insane,” said Edwards’s mother, Marina Pope, who found the rental house on the Internet following her own divorce and a foreclosure. “I was in a rushed situation. I would never recommend this company to anyone.”

Tenants in dozens of homes in two of the company’s largest markets, Atlanta and Los Angeles, told Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting similar stories. Most of the homes were former foreclosures, bought between 2012 and 2015. In many cases, the house’s former owner and occupant had been wiped out by the housing bust.

Viewed from the outside, most of these houses look nice—set back from the street, with manicured lawns. Most are in the suburbs, in good school districts. But inside, many of the properties visited by Reveal look like they’ve been severely neglected. Like Edwards, other renters were struggling without heat and coping with leaky roofs. Some faced peeling tiles, collapsing counters, even a snake infestation.

“safety hazard!!!” a county code inspector near Atlanta wrote in his report of a ceiling leak that channeled water through a light fixture when it rained. A month later, the leak continued.

Tom Barrack, 70, is among the winners of the US housing crisis, which washed away the wealth of millions of people. Today, his rental empire spans at least 10 states, from California to Florida. In a speech to a University of Chicago real-estate conference in 2012, Barrack—tall, fit, pacing the room like a motivational speaker—likened managing thousands of homes across the country to running a chain of Kinko’s copy shops. His secret? “Acquisition [and] retrofit” a property and then rent it out, he told the audience. “I can’t get a plumber to come to my house for $1,500 an hour,” he added. “We retrofit many of these houses for $1,500 total.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

An emerging body of evidence tells the other side of that story. For starters, while Barrack’s company puts $19,000 into these homes when it buys them, it spent just $800 on maintenance per home in 2016, according to the company’s most recent annual prospectus.

Nationally, the Better Business Bureau reports “a pattern of complaints concerning billing or collection issues [and] repair issues” at Colony-owned homes, which are rented under the trade name Waypoint. The litany of problems posted on the bureau’s website includes broken air conditioners, flooding, mold, and serious infestation. “When consumers attempt to reach the business regarding repair issues, they report that the business is unresponsive,” the bureau said.

Both Barrack and representatives from Colony declined to be interviewed for this story. In a statement, Charles Young, the company’s chief operating officer, said, “Colony Starwood Homes plays an important role in providing high-quality and affordable rental housing for thousands of Americans.” The company claims high marks for maintenance, saying that in a recent customer-satisfaction survey it received 4.6 out of 5 possible points. “We are honored to serve the thousands of renters across the country who call our properties home,” Young said in the statement.

In the heart of Colony’s largest market, however—Fulton County, Georgia—the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta found corporate landlords were much more likely to file eviction notices than mom-and-pop landlords. And Colony was the most aggressive of these corporate landlords, the report’s data show; in 2015, Colony moved to evict one-third of its tenants. In its statement to Reveal, Colony disputed the Federal Reserve Bank’s study and said most residents who receive eviction notices are not actually forced to leave. The company said that it kicked out only 10 percent of its Fulton County tenants in 2016.

The Federal Reserve’s researchers also found that the impact of the company’s actions wasn’t felt evenly across the community: African-American neighborhoods bore the brunt of the aggression. “Given the public debate, we expected to see that gentrification was a major cause of evictions,” said Elora Raymond, lead author of the Federal Reserve report, told Reveal. But the Fed’s analysis in fact found one factor that seemed to predict whether a tenant would get an eviction notice: “the concentration of blacks in the neighborhood.”

In Los Angeles, Colony tenant Evelyn Knights received a three-day eviction notice over $49.33 past due in November. Knights, who is African American, previously owned a home in South Los Angeles, but she lost it to foreclosure after her husband died. Now she pays $2,125 a month to rent a similar bungalow 10 miles away.

“It’s hard,” Knights, 62, said through the metal security gate at her front door. “I’m on a fixed income and so I have to keep moving money around. Let this go to pay the light bill, let that go to pay the telephone bill.” She said that she was able to keep her home only after asking her church for help. “At that time, I didn’t even have $49.33,” she said.

Barrack and Trump

Tom Barrack and Donald Trump have known each other for more than 30 years; they’ve been friends since Barrack brokered the sale of New York’s famed Plaza Hotel to Trump in the 1980s. Since then, the two real-estate moguls have joined forces on numerous occasions, most recently on Trump’s proposal to turn the Old Post Office in Washington, DC, into a 263-room Trump International Hotel. Barrack bowed out after Trump said he didn’t need help financing the project.

By then, Barrack was working full-tilt to get Trump elected. He was one of the first business leaders to endorse Trump’s presidential campaign, and after Trump became the presumptive Republican nominee, he hosted one of the campaign’s first big-ticket fundraisers. He went on to introduce Ivanka Trump at the Republican National Convention, saying he felt like “the anchovy on Ivanka’s Caesar salad. I know you’re salivating for that and you’re gonna get it.”

Barrack helped put at least $130 million into Trump’s campaign coffers: He raised $23 million for the pro-Trump Rebuilding America Now Super PAC and, as chair of the inaugural committee, helped raise $107 million more. When candidate Trump faced fraud charges and a class-action lawsuit brought by students of the now-defunct Trump University, it was Barrack who found him a lawyer, according to The Hollywood Reporter.

The New York Times has called Tom Barrack “one of the few people whom Mr. Trump trusts.” On February 21, after he and Trump shared a meat-loaf lunch at the White House, Barrack told CNN that they talk every day.

Barrack has also been linked to some of the scandals involving the president. The New York Times reported that Barrack introduced Trump to campaign manager Paul Manafort, now at the center of investigations into possible election rigging by Russia. The Washington Post revealed that Barrack helped Trump’s son-in-law and White House adviser Jared Kushner avoid foreclosure on a 41-story Manhattan office tower Kushner bought shortly before the bust.

There are signs that Trump is now moving to help Barrack and other corporate landlords. An hour after Trump took the oath of office, his administration reversed a President Barack Obama–era rule that would have made mortgages backed by the Federal Housing Administration more affordable to borrowers who had good jobs but lacked enough money for a down payment—exactly the sort of people Barrack’s company targets as renters of his single-family homes.

Trump’s policy reversal was condemned by both realtors and consumer groups, who argue that keeping such people out of the home-buying market—and in high-price rentals like Colony’s—could lock in economic inequality over generations. “If you can’t own a home, you can’t build wealth,” said Stella Adams, chief of civil rights for the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. “And if you can’t build wealth, you can’t have the economic mobility that’s been the gift of every generation before.”

Barrack Profits Off Distress

The son of a Lebanese grocer, Tom Barrack presents himself as a renaissance man: an enthusiastic horse-polo player, a Bordeaux-style winemaker, and an avid surfer not afraid to be photographed shirtless alongside his friend the actor Rob Lowe.

But Barrack’s primary business for decades has been profiting from other people’s pain. He bought the Neverland Ranch from Michael Jackson shortly before the King of Pop’s death in 2009, and became famed photographer Annie Leibovitz’s sole creditor when she was threatened with bankruptcy in 2010.

His biggest paydays have come when he bet against conventional wisdom. In the aftermath of the savings-and-loan scandal in the 1980s, he teamed with Texas financier Robert Bass to buy a portfolio of bad loans held by American Savings, a failed thrift that had been taken over by the FDIC. The men then sold the loans back to their original borrowers, turning a $400 million profit, according to Fortune.

“This is my investment philosophy,” Barrack said in his University of Chicago speech in 2012. “You walk into a jungle where no one else wants to be and you swing and you fight and you bite and eventually, if you’re successful, they’re all swinging with you and then you’ve got to move to another jungle.”

“He who can sustain the most pain wins,” he said.

Barrack saw the housing bust coming, predicting in the 2005 magazine profile that the real-estate market would collapse just as the dot-com boom had fizzled a few years before. When the recession hit, he was ready.

Between 2008 and 2013, Colony Capital became the largest purchaser of distressed assets from failed banks under the FDIC’s structured-transaction sales program, buying $2.3 billion worth of commercial and residential real-estate loans for less than 25 cents on the dollar. In 2012, at the bottom of the housing bust, Colony began buying up actual houses, too, and turning them into rental properties.

The government helped him get started. In November 2012, Barrack’s firm went into business with Fannie Mae, buying an equity stake in 970 foreclosed homes that had fallen into the hands of the government-controlled mortgage company. Colony paid $35 million for an ownership share of the bundle valued at $157 million. Under the terms of the deal, Colony was allowed to keep a share of the rents along with a fee in exchange for its management work. Together with Fannie Mae, Colony still owns and runs many of these homes.

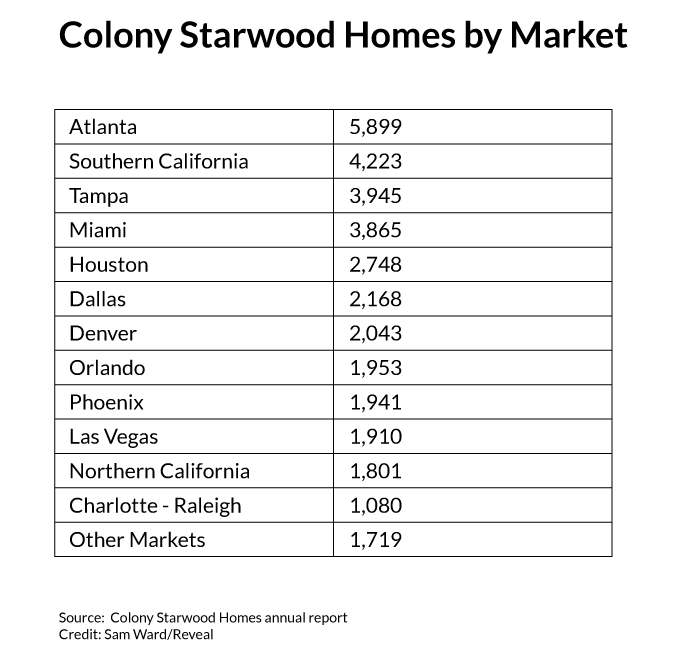

Over the next three years, Barrack’s company acquired 20,000 homes. Its purchases focused on suburbs in the Sun Belt—from Los Angeles and Phoenix to Atlanta and Miami. Last year, Colony merged with one of its rivals, Starwood Waypoint, creating an empire that manages more than 35,000 homes. The combined company now controls more than $6 billion in residential real estate, mostly houses lost by their previous owners through foreclosure during the Great Recession.

In interviews, most tenants told Reveal they had no idea who owns their house. The one name they will never see on paperwork is Colony. The combined company’s forward-facing brand is Waypoint Homes. Tenants pay their rent to Waypoint and call Waypoint’s toll-free 800 number when something breaks. But if tenants get hit with an eviction notice, or if they want to take their landlord to court, they find that Waypoint Homes owns no property.

The homes’ legal owners, mentioned once across the top of the lease, are spread across dozens of limited-liability companies. These faceless entities are usually named for mortgage-backed securities and are registered to suites in office parks in Wilmington, Delaware. It’s lawyers for those companies who file eviction notices when Colony’s tenants fall behind on the rent.

“They’re the ultimate absentee, far-removed, out-of-state landlord,” said Michael Lucas, deputy director of the Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers Foundation, which represents tenants pro bono in Colony’s largest market. He also coauthored the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta report on evictions by corporate landlords.

“You don’t have a landlord who gets to know the tenant,” Lucas added. “Instead, they are a massive bureaucracy not unlike the servicers of all the mortgages that went bad, and they’re just making a decision: On the 5th we evict, or whatever it is.”

Makita Edwards’s experience is instructive. Last September, after the 25-year-old mother’s experience with the collapsed ceiling fan, she fell behind on rent and received an eviction notice. If she wanted to stay, the attorney for Colony’s company said in a court filing, she needed to pay not only her past due rent but also a $95 late fee, $60 in court costs, and a $25 charge for the process server who delivered the eviction notice.

Edwards paid those charges, but her family was already living on the edge. Spending the extra $180 made her late on October’s rent, leading to another round of additional charges. Over the next six months, her family paid more than $1,000 in fees. “It just starts that spiral downward and the tenant can’t keep up,” Lucas said of such fees.

The fees are a gold mine for Colony, however. The company’s stock filings show that last year it made $14 million from fees and another $12 million on so-called tenant clawbacks, including seized security deposits.

As for Tom Barrack, he’s already cashing out. Last October, a month before his good friend Trump was elected, Barrack off-loaded three-quarters of his stock in Colony Starwood Homes, then valued at $728 million. This spring, Barrack and his investment firm sold about half of their remaining stock. On a single day in March, Barrack personally made $127 million. Now the billionaire is building a 77,000-square-foot mansion high above Los Angeles. When it’s finished, the estate will boast breathtaking views of the Pacific, three fountains, two swimming pools, one tennis court—and 10 bedrooms just for the help.