A monthly gathering of personal enthusiasms and observations about the passing scene, Field Notes will, in the tradition of The Nation, draw attention to things overlooked or often misunderstood.

This first installment of Field Notes celebrates the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, where the story of American art is being rewritten in museums across this country, and its corollary in music, Dust-to-Digital. This dispatch pursues the notion that cultural currents in the South flow in a deeper, healthier, and more progressive direction than frequently credited. That theme may reappear from time to time amid other dispatches on culture and politics, where the heat of the political moment also obscures a quiet revolution that deserves our attention and should fuel our optimism: brave new directions in young adult fiction; the mobilization of teenage activists by Generation Citizen; art-world facts and follies; and dispatches from the front lines of prison reform.

A miscellany of things, to be sure—but all of them important to an observer eager to spread the word.

Souls Grown Deep

I’ve known rivers;

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than

the flow of human blood in human veins…My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

—Langston Hughes

Bad habits die hard, but now and then they fade away, clearing the air for a little fresh thought. There is a breeze blowing through the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York just now, where History Refused to Die: Highlights From the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift, an exhibition of 30 works by African Americans made in the South between the civil-rights era and the early years of the present century, has swept aside the patronizing labels attached by critics and historians to art they can’t easily account for. Neither folk, outsider, self-taught, nor outlier, this work by little-known artists touched with greatness is exhibited on its own merits. Made mostly of found materials in isolated communities, it speaks eloquently, if paradoxically, of a better country than the one we know or think we know.

Of the 57 works the Souls Grown Deep Foundation gave the Met, a few of the 30 on view are not entirely unfamiliar, though showing them in conversation with one another renders visible the African roots of African-American art (much as Robert Farris Thompson’s landmark Flash of the Spirit did, decades earlier). There are 10 quilts by Loretta Pettway, Annie Mae Young, and other artists of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. Thornton Dial (1928–2016), another native of Alabama, is here too; although he’s had a following for many years, his six assemblages on display—especially the gigantic one that gives the exhibition its name—belong to a different order of greatness with their muscular commentary on American history. Poor, mostly uneducated, and isolated in the town of Bessemer, Thornton Dial understood more about this country than Jeff Sessions ever will.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The show ends with Dial’s ironic Victory in Iraq (2004), a relief painting composed of a mannequin head, barbed wire, steel, clothing scraps, tin, electrical wire, wheels, stuffed animals, toy cars, figurines, and paint. The curators have been bold enough to separate it from the rest of the exhibition and display it in an adjoining gallery alongside Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and other abstract expressionists. Go see for yourself how those art stars fare in proximity to Dial. His work is intricate, visceral, and overwhelmingly aware of the world. Photographs are insufficient.

Lesser-known artists in the exhibition such as Lonnie Holley, Ronald Lockett, Nellie Mae Rowe, and Joe Minter combine a sure aesthetic sense with equally pungent references to matters both close to home (Minter’s Four Hundred Years of Free Labor, 1995), and national (Lockett’s The Enemy Among Us, a meditation on the Oklahoma bombing, 1995).

If Souls Grown Deep’s placement of this art in the Met—as well as in many other major museums across the country—has erased old labels and shown that it is important on a global scale, it also has the potential for doing far more by interrupting and revising the story of American art. That will take time. The Met has made a beginning with this exhibition and a fine catalogue with four careful essays on the work, and yet I could not get a satisfactory answer when I asked how many of the 57 works will be on permanent display after the exhibition closes on September 23. A piece here and there, as I understand it. I dream of a donor who will fund a permanent gallery so that Lonnie Holley, Joe Minter, Ronald Lockett, Thornton Dial, Nellie Mae Rowe, and Loretta Pettway can be seen by every visitor just as Winslow Homer, Georgia O’Keefe, and Andy Warhol are. Someday, maybe.

In the meantime, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, New Orleans Museum of Art, Atlanta’s High Museum, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Virginia Museum of the Fine Arts, as well as several historically black colleges and universities are rolling out their exhibitions of art from Souls Grown Deep, keeping the story alive. This has been founder William Arnett’s goal since he created the foundation in 2010: to build bridges to other institutions by distributing its 1,200 works across the country.

The story of Arnett’s collection began in the 1980s, when he returned to the South after a few years abroad collecting Asian and West African art. An introduction to Dial and the nearby quilters of Gee’s Bend proved revelatory, and set him on the path to forming Souls Grown Deep. At every step he seems to have operated in an exemplary, if obsessive, manner. In addition to gathering the art and loaning it to earlier exhibitions across the country—including the 2002 Whitney blockbuster The Quilts of Gee’s Bend—Arnett invited well-known scholars and eminent artists to write about the work for a huge two-volume set published by his imprint Tinwood Books. He also assembled a massive archive of photographs, oral histories, and other materials now housed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where—along with art the foundation has donated to the university’s Ackland Art Museum—it has become a major resource for teaching and scholarship.

Dust-to-Digital

“The concept of Dust-to-Digital is something…. It’s almost biblical. But it’s voice. It’s not so much digital images, but it’s digital sound that can take people back and remind them of what these humans went through, their stories!”

—Lonnie Holley, musician and artist

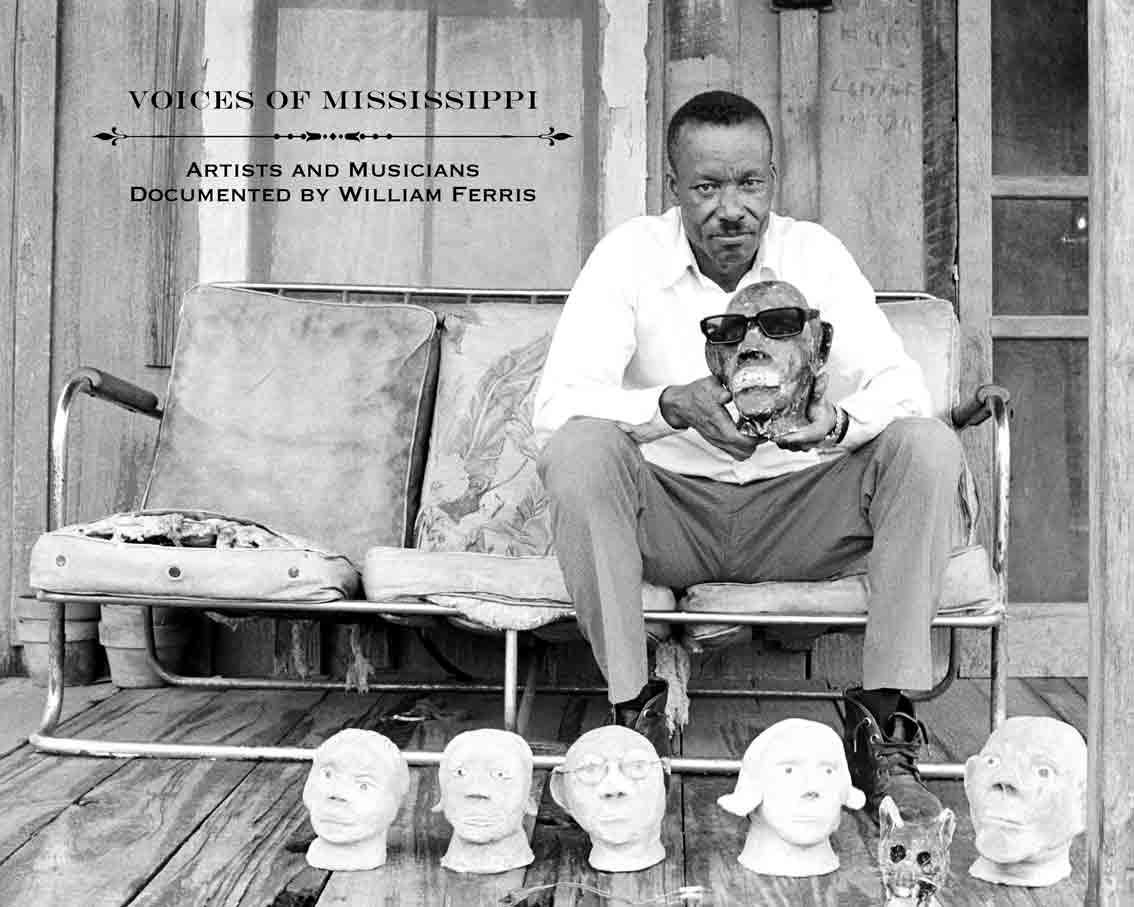

If Arnett has changed the story of American art, his work is part of a broader current that has been flowing through the South for years now and transforming our picture of its culture. The interconnections are many. One of my favorite artists in the Souls Grown Deep collection is James “Son Ford” Thomas, a Delta blues guitarist who also made sculptures. Son Ford’s life and work have been documented for decades by William Ferris, eminent professor of history at UNC Chapel Hill and eminent documentarian of film, music, art, storytelling—of virtually everything in Southern folk life and culture of the mid-20th century and onward. Asking Bill about Son Ford led me to Dust-to-Digital, where April and Lance Ledbetter have been rescuing blues, gospel, film, photography, and much else since 2003. They have now produced Voices of Mississippi: Artists and Musicians Documented by William Ferris, a handsome boxed set (three CDs, a DVD, and a book) where one can look at Son Ford’s work, hear him talk, and listen to his music along, with that of many other musicians and artists patiently recorded by Ferris—even including a bit of Eudora Welty chatting about the South and reading a passage from “Why I Live at the P.O.”

Dust-to-Digital issues the kind of box set you can imagine Bob Dylan giving to Neil Young—something he actually did, sending off Goodbye Babylon, a collection of great early gospel music in its handsome wooden box, to the grateful Young. The sound quality of everything the Ledbetters issue is astonishing; their care with documentation and the artistry of their presentation imaginative and thoroughly satisfying; the significance immeasurable. I’m especially fond of the two-volume Art of Field Recording, a compilation of traditional American music recorded by Art Rosenbaum and delivered with eight CDs and two books of excellent photographs, commentary, and Rosenbaum’s evocative drawings and paintings.

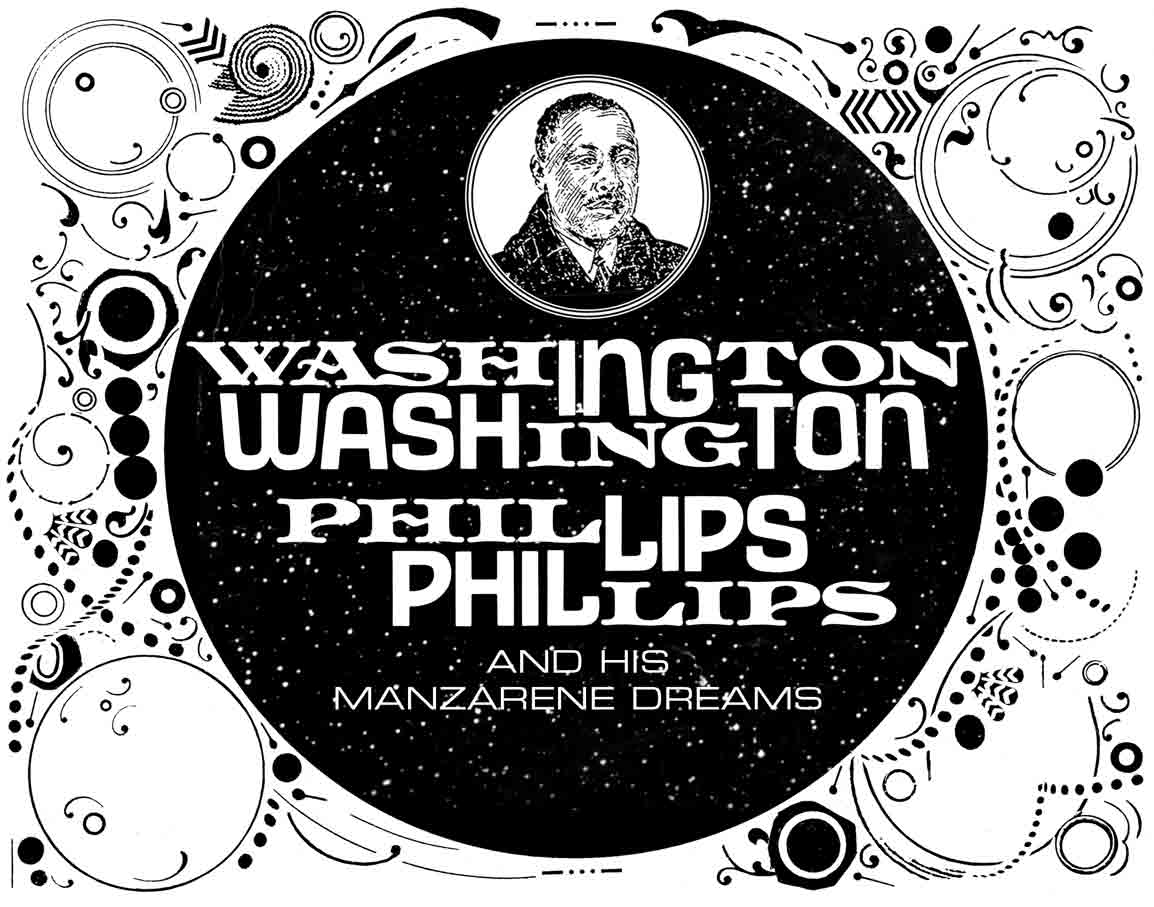

Among Dust-to-Digital’s most unexpected discoveries is the book-and-CD set Washington Phillips and His Manzarene Dreams. Phillips (1880–1954) sang Christian blues and accompanied himself on a homemade instrument with a strange and heavenly sound. The reissue straightens out his biography and the story of his “manzarene” in a handsome little volume that accompanies the CD. Vintage photographs, lyrics, and historic documents are all folded into the book, as they are with most Dust-to-Digital projects.

But Voices of Mississippi, the digitization of Bill Ferris’s archives, is in many ways the perfect complement to the work of Souls Grown Deep. Ferris is as unobtrusive as Arnett has been explosive and that modesty has served him well: at Yale where he introduced his students to Son Ford, B.B. King, and other emissaries from the world of blues and roots; at the University of Mississippi’s Center for the Study of Southern Culture, which he founded while at Yale; in his travels making photographs alongside his friend William Eggleston; even as head of the National Endowment for the Humanities in the Clinton administration. There is important music here, important stories and photographs, and indelible films all depicting a way of creative survival that is indestructible, despite heavy odds. No one will pass this way again.

What Bill Ferris knows, he has learned through what Tom Rankin describes in the box set’s introductory essay as “the patience of his considered listening.” He gets out of the way. If there is a royal line of succession from Alan Lomax to Fred Ramsey, Harry Smith, and Art Rosenbaum, it culminates in Bill Ferris and the work of Dust-to-Digital.