Some 6,000 inmates serving time for drug crimes were released early from federal prisons over the weekend. One of the most pressing questions facing the newly freed is where they’ll live. Many are likely to end up on the street: More than half of all the homeless in the United States were once in prison, thanks in part to discrimination that’s baked into the housing system.

On Monday President Obama announced a series of measures intended to help the formerly incarcerated find jobs and homes. Most of the attention has gone to his show of support for “banning the box” that forces people to reveal criminal convictions on job applications. Over 100 cities and counties, and 19 states, have already done so. Now, under Obama’s executive order, the federal government will delay inquiries about an applicant’s criminal history until late in the hiring process.

The White House also took an essential but overlooked step towards undoing some of the draconian housing policies that have made it difficult for returning citizens to rejoin their families and stay off the streets. Local public housing authorities can no longer use arrest records as “the sole basis for denying admission, terminating assistance or evicting tenants,” according to the new directive from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. HUD also reminded local authorities that “one strike” rules requiring rejection for any type of criminal activity aren’t mandated by federal policy, a common misconception. The agency will spend $1.7 million to help public-housing residents under 24 to expunge their records, and another $8.7 million for Permanent Supportive Housing for the newly released.

“In the context of policies to support reentry, safe and stable housing has incredibly powerful anti-recidivism effects, and yet many people who are released from incarceration have no idea where they’re going to live. About one-third expect to go to homeless shelters upon release,” said Rebeca Vallas, the director of policy for the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress.

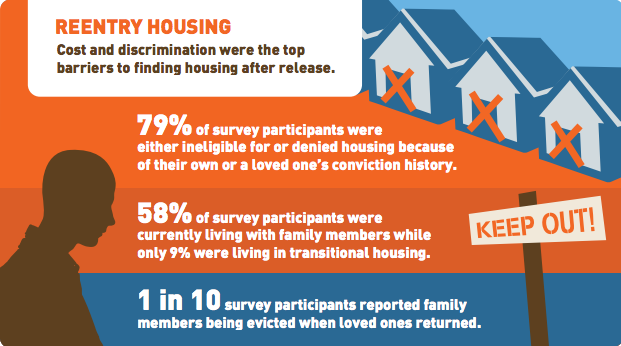

Rules vary by city, but many local public housing authorities exclude people with a criminal record either completely or for several years, exacerbating bias that exists in the wider housing market. In a recent survey of formerly incarcerated people and their families, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights found that 79 percent of respondents had been denied housing because of their own criminal record or a relative’s. One in ten reported that family members were evicted when their relatives returned from prison. Because of racial disparity in the criminal justice system, these barriers to housing likely have a disproportionate impact on people of color.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

One of the people responsible for the state of affairs is Bill Clinton, who as president pushed HUD to penalize housing authorities that didn’t exclude people with criminal histories. “If you break the law, you no longer have a home in public housing, one strike and you’re out,” Clinton announced in 1996. Two years later he signed the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act, which made certain types of offenders ineligible for public housing. That law also gave local housing authorities more latitude to discriminate against applicants or evict residents based on “other criminal activity,” a squishy standard that led some landlords to use arrest records as a disqualifying factor.

“These policies were promulgated with the idea of protecting residents and public safety, but the result has been just really, really harsh on anyone with criminal-justice involvement, and on families,” said Alison Wilkey of the Prisoner Reentry Institute at John Jay College. “Given the racial disparities in arrests, this is a pretty big step—to say that an arrest alone doesn’t mean you can deny someone admission to public housing and doesn’t mean you can evict someone.”

In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled against four elderly plaintiffs who’d been kicked out of public housing units after their younger relatives were caught with drugs. The court found that public-housing authorities could evict tenants for family members’ drug-related activity, “regardless of whether the tenant knew, or should have known” about it. That opinion is widely misinterpreted to indicate that local authorities must adopt one-strike eviction policies for all offenders, according to Bruce Reilly, deputy director of Voice of the Offender in New Orleans. The clarification from HUD is intended to correct that assumption. (Sex offenders and people convicted of meth production are permanently ineligible.)

“Folks who work for those housing boards and agencies, they don’t know the laws front to back and they’re not necessarily housing lawyers,” Reilly said. “If you have a record you are not automatically barred from public housing, but that’s the word on the street, the common knowledge. That’s one of the strongest most powerful and potent myths that holds back entire families.”

The new directives from HUD still leave local authorities with a lot of discretion to bar applicants with a criminal background—too much discretion, Reilly and other advocates say. In New York, for example, someone with a Class E felony—the lowest felony charge, usually carrying a sentence of up to four years in prison—and their family members are ineligible for housing until five years after they’ve completed their prison sentence and parole. “The federal government could prohibit housing authorities from adding on their various discretionary sanctions against people with criminal records,” said Susan Burton, who founded a reentry organization, A New Way of Life, in Los Angeles after she got out prison. “The person who has been convicted has served their time. Why would we continue to punish and exclude them from housing and jobs? Those are the primary areas that allow people to get their lives back on track.”

A number of cities have started to rethink their housing policies in recent years, in many cases because of organizing campaigns led by ex-offenders and their allies. The backlash to the war on drugs and a corresponding shift in perspective at HUD has also helped; in 2011, then-Secretary Shaun Donovan sent a letter reminding public housing directors “that people who have paid their debt to society deserve the opportunity to become productive citizens and caring parents…. Part of that support means helping ex-offenders gain access to one of the most fundamental building blocks of a stable life—a place to live.”

New York and Los Angeles are among the cities that are allowing some recently released prisoners to live in public housing, though the pilot programs there are small. In 2012, the Housing Authority of New Orleans acknowledged that a criminal background is “a likely bar to admission to most affordable housing opportunities” and that its own “practices have served to perpetuate the problem.” The new policy prohibits exclusion based solely on criminal history, but it has yet to be fully implemented. Other places have tried to stamp out discrimination in the housing market more broadly. In Oregon, for instance, landlords can no longer refuse to rent to someone because of an arrest record or particular criminal convictions.

It’s progress, but of a patchy sort. That’s why advocates would like HUD to bring reluctant public-housing directors along more forcefully. “We’ve had forty years of tough on crime and tough on people policies,” said Burton. “What’s happening is a start, but does it go far enough? Not yet.”