The Police Take City College

Scores of people were arrested at the City University of New York on Wednesday—a scene “very reminiscent of the 1968 police crackdowns” at Columbia University, said one protester.

City College Gates at 139th Street and Amsterdam Avenue in the early hours of May 1.

(Photo: Nicolas Niarchos)At around 12:45 am on Wednesday, two white police buses rolled away from the City College of New York (CUNY) campus, in Hamilton Heights. For a second, there was a flash of a young man’s face, then a head wrapped in a keffiyeh. The passengers were students who had been arrested in the late hours at the Gaza Solidarity Encampment that had been occupying a plaza on campus to protest the war in Gaza.

A crowd of protesters gathered at the intersection of 139th Street and Amsterdam Avenue began to cheer at the bus. “Students, students make us proud!,” they chanted. “Hold your ground, hold your ground!”

“They were kettling us and picking people off from the group to arrest them violently. I saw people being thrown to the ground and, eventually I was stuck with a small group of people linking arms in front of the gate,” Jarrett Moran, an adjunct professor of English at CUNY, told me. “The cops dispersed us and entered the campus to arrest the students at the encampment.”

Police arrested some 173 people, and protesters saw officers with tasers come onto campus and tackle unarmed students. Videos posted on social media showed students who had been pepper-sprayed and police with bundles of zip ties attached to their belts chasing students. According to a press release by the student group CUNY 4 Palestine, police broke an undergraduate’s ankle and smashed the teeth of two protesters.

The next morning, Mayor Eric Adams told a press conference that some 300 people had been arrested at Columbia University and at City College.

Roscoe, one of the protesters who had been further inside a police cordon, told me that he had seen six police buses outside City College, and scores of students being arrested. (Most of the protesters I spoke to said they did not want to be identified by name because of concerns of reprisals.) “What is happening here tonight is very reminiscent of the 1968 police crackdowns,” he said, recalling when police reacted violently to anti–Vietnam War protests on Columbia University’s campus 56 years ago to the day. “A lot of the cops might have come up from Columbia.”

At Columbia, confusion reigned as police erected barricades in a wide perimeter around the campus, as riot police removed students who had occupied Hamilton Hall. Press were not allowed inside. Students inside the campus broadcast on WKCR, Columbia’s student radio station, describing police sweeps of the campus, and student journalists sheltered at the Journalism School, where Jelani Cobb, the journalism dean, was reportedly threatened with arrest when he advocated for the rights of journalists. (Cobb later called the events “tragic” on MSNBC.)

Columbia has been the focus of media coverage these last days, and Moran said that the lack of focus on City College offered its own set of challenges. “City College and the CUNY colleges I do think get overlooked. The students protesting are in many ways more vulnerable there,” he said. “They’re Black and brown students. Many are first-generation immigrants, working-class students. But the narrative, around, you know, an Ivy League campus in New York gets a lot more media attention.”

The City College encampment was no less focused than the one at Columbia. For the past week, a group of perhaps a hundred students had gathered around a flagpole on campus, camping out in tents, listening to speeches, and organizing teach-ins.

I visited on Monday and watched as students gave speeches about colonialism in the hot, sunny afternoon, and prayed the Asr, the Islamic afternoon prayer, on a lawn. Maria, a freshman CUNY student, told me that it was her first time there. “I’m learning a lot,” she said. The numbers ebbed and flowed as students came to support the protest.

“It was incredible when I was there. There were people teaching colonial history to groups of students,” Moran, the professor, told me. “There was a really good, supportive, energy. I feel like it was what a university campus should feel like.”

Attached to the flagpole at the middle of the campus were the students demands to the university administration: “1. Divest, 2. Boycott, 3. Solidarity, 4. Demilitarize, 5. A people’s CUNY.”

Somebody had taken down the United States flag and replaced it with a Palestinian one.

The university, however, saw the protest not as a peaceful manifestation but as a situation that offered “heightened challenges,” as City College President Vincent G. Boudreau put it in a statement. There were reports of broken windows at the university’s campus, although the encampment had tried to enforce a strict no-graffiti and no-property-damage policy. “Most importantly, this is not primarily a CCNY demonstration, and perhaps not primarily a CUNY demonstration,” Boudreau said. “The significant inclusion of unaffiliated external individuals means that we don’t have established connections to them.”

Mayor Adams at his Wednesday morning press conference said that he supported freedom of speech, but blamed “outside agitators” for violence. “We saw that there were those that were never concerned about free speech,” he said. “They were concerned about chaos.”

“I’ve seen a lot of that narrative,” Moran told me. “I saw my own students at the encampment when I was there. I saw fellow CUNY faculty members and students also at the protest last night.”

“What I saw was the president of CCNY gave authorization for the NYPD to move into the campus,” Daniel, a Hunter college alumnus who managed to get out of the encampment told me. “Vincent Boudreau—he specifically gave authorization. It wasn’t the chancellor. It was the City College president.”

“Before everything happened, they blocked all entrances to campus and they wouldn’t let anyone in or out, which is completely against the tradition of CUNY,” he added. “By the time [the police] moved in, there were maybe 50 to 100 people in there, and there were hundreds of police officers and they just entered in, broke down the barricades, started ripping down tents, started humiliating people. I saw people getting thrown onto the ground.”

When the students were cleared from campus, police took down the Palestinian flag and hoisted the US flag. “An incredible scene and proud moment as we have assisted @CityCollegeNY in restoring order on campus,” Kaz Daughtry, the NYPD’s deputy commissioner for operations wrote on X.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

At 139th Street, several people told me that they were CUNY or City College students. Others told me they had come to support the students. Hilal, a young man with his head wrapped in a red-and-white keffiyeh brandished a Yemeni flag. (Yemen’s Houthi rebels have bombarded shipping in the Red Sea.) He told me he had traveled from Westchester to show solidarity. His parents came to America, he told me, from the Yemeni city of Ibb. “I think it’s very peaceful,” he said when I asked him about the protest. “It’s the students showing their opinion on what’s happening, and their voices should be heard by the administration, by the people in charge.”

Just after 1 am, the police retreated across Amsterdam Avenue under a cold drizzle. A master’s student read a note she had received on her phone from organizers. A small group of protesters continued to chant, but she urged them to head downtown, to One Police Plaza, to protest in support of the arrested students. Lawyers were needed. “If you have legal training, they need all the help they can get,” she said. “Just go to one Police Plaza. You will meet—you will find people there.”

More from The Nation

What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer’s latest film, The End, is a Golden Age, postapocalyptic musical crying out from the depths of the earth.

What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America

When social structures corrode, as they are doing now, they trigger desperate deeds like Mangione’s, and rightist vigilantes like Penny.

Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk

Far from being an alien interloper, the incoming president draws from homegrown authoritarianism.

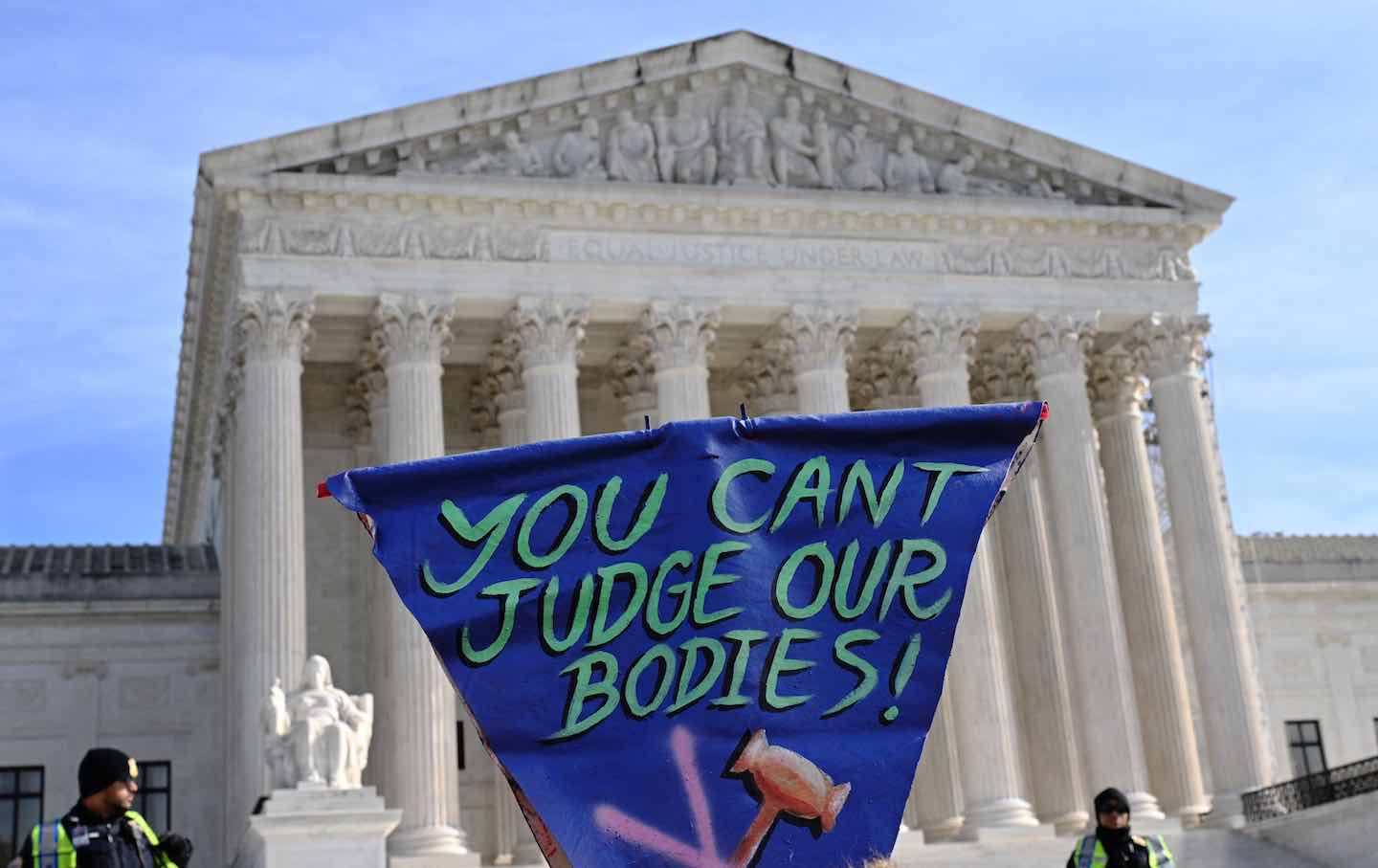

Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm

Contrary to what conservative lawmakers argue, the Supreme Court will increase risks by upholding state bans on gender-affirming care.