Is America’s political discourse on inequality finally getting real?

In the early going of the 2020 presidential campaign, this has become a question worth asking. White House hopefuls have been condemning the maldistribution of America’s income and wealth with an intensity—and a specificity—that would have been unimaginable just a few years ago. And the rich are squirming. They see candidates proposing unprecedented taxes on their assets and even questioning their right to exist. Perhaps most worrying, this time moderates aren’t exactly rushing to their defense.

At the October Democratic primary debate, for instance, Senator Bernie Sanders delivered one of his trademark blasts against the billionaire class.

“Senator Sanders is right!” responded the wealthiest candidate in the Democratic field, Tom Steyer.

That gave Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar, a self-styled champion of moderation, an opening for the evening’s biggest laugh line. “No one on this stage wants to protect billionaires,” she pronounced. “Not even the billionaire wants to protect billionaires!”

A good many billionaires, of course, do expect to be protected, and the unwillingness of the 2020 Democratic field to fawn over their fortunes has the awesomely affluent feeling like a persecuted minority. The nation’s richest may not have felt this aggrieved since President Franklin Roosevelt declaimed, “I welcome their hatred,” back in the 1930s. Calls for a wealth tax—Senator Elizabeth Warren’s signature initiative—have our deepest pockets particularly pained.

“This is the fucking American Dream she is shitting on,” as billionaire Leon Cooperman told Politico.

Has campaign 2020 indeed put America’s superrich at existential risk? Or are our wealthiest merely hyperventilating? The Nation and the Institute for Policy Studies, the publisher of Inequality.org, decided to find out. IPS analysts first prepared a candidate questionnaire designed to divine the depth of each presidential hopeful’s commitment to challenge inequalities of income and wealth. The survey then went to all the major party candidates, Democrats and Republicans alike.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

But candidates have a nasty habit of ignoring questionnaires that leave them uncomfortable. So IPS analysts also scoured the printed and online record for the candidates’ inequality-related plans and comments.

What has all this sleuthing found? Those who seek our nation’s highest office—at least on the Democratic side—no longer see safe harbor in the warm embrace of the ultrarich. To be sure, our political class has not yet abandoned the billionaire class. But the political consensus that nurtured our contemporary top-heavy economy has cracked.

To appreciate just how much, we need to start with a little history.

In the early 1900s, after a generation of Gilded Age excess, American progressives of most every stripe arrived at a broad common vision of how best to mold a decent society. The nation needed, reformers and revolutionaries agreed, to narrow the grand divide that separated the nation’s poor many from its most privileged few, and that meant focusing on both the absence of wealth and its concentration. Americans needed to battle, as publisher Joseph Pulitzer put it, “predatory poverty” as well as “predatory plutocracy.”

This commitment to leveling up the downtrodden and leveling down what the philosopher Felix Adler termed “pomp and pride and power” would animate struggles for justice throughout the decades ahead and dominate the New Deal’s political discourse. The same egalitarian ethos would guide us through World War II and into the postwar world.

But this progressive consensus on inequality did not survive the Cold War. With the capitalist-boss-baiting Soviet Union our archenemy, anyone who continued to trumpet New Deal distributional themes was suddenly deemed dangerously subversive. By the early 1960s, top Democrats were no longer talking up the importance of taxing the rich. John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier assured Americans instead that a “rising tide lifts all boats.” We needn’t worry about the wealthy, the new party line went. If we just cut taxes to grow the economic pie, everyone could get a bigger piece.

By the 1990s, with no one in political power worrying about the wealthy, the predictable had taken place: America’s richest had become fabulously richer, amid rising poverty and flatlining wages. Republicans and Democrats shared responsibility for this. Both parties deregulated and privatized. Both lavished subsidies on the wealthy and their enterprises. Both hailed the rich as job creators.

“I’d like to create more millionaires than were created under Mr. Bush and Mr. Reagan,” Bill Clinton even opined in 1992’s first general election presidential debate.

Clinton succeeded at that task, as has every president since he left office. Will that pattern change if voters choose one of the candidates running to replace Donald Trump? Are these office seekers pushing policies and programs that hold out hope for a significantly more equal America?

Class wars unfold on multiple fronts, and virtually all national policies and programs affect how equally we distribute our income and wealth. But some fronts affect income and wealth distribution more directly than others. The Nation/IPS inequality questionnaire highlights these battlefronts, focusing on struggles that involve everything from taxes and intergenerational transfers of wealth to CEO pay and the composition of corporate boards.

The questionnaire is online at inequality.org/2020, as are the candidates’ full responses. No candidates seeking the GOP’s 2020 nomination chose to complete the survey, and none of them have made much of an effort on the campaign trail to address the inequality concerns that it raises.

The Democrats who chose not to complete the survey, by contrast, have commented on many of the questions it poses. The profiles that follow rest on those comments as well as the completed surveys. The profiles appear in order of the latest national poll standing.

Joe Biden

The United States, the Biden campaign proclaims, “wasn’t built by Wall Street bankers and CEOs and hedge fund managers.” We need “an economy that rewards those who actually do the work.”

On the other hand, he told deep pockets at a Manhattan fundraiser this June that we don’t need “to demonize anybody who has made money” off our existing economy. “Nobody has to be punished” to address “income inequality as large as we have,” he added. In a Biden administration, “nothing would fundamentally change.”

What exactly does he mean by that? We don’t know. His campaign didn’t complete the Nation/IPS inequality questionnaire and hasn’t released plans detailed enough to judge a Biden administration’s overall impact on inequality. We do know that Wall Street bankers, CEOs, and hedge fund managers consider Biden’s tax plan “far less extreme” than those of his two chief rivals, Warren and Sanders, according to a Forbes analysis.

Biden has not proposed a wealth tax or a marked increase in the highest income tax rate. And unlike most other top Democratic presidential contenders, he has not yet supported a financial transaction tax targeting Wall Street highfliers.

Still, the wealthy would feel pinched if the proposals Biden endorses turned up in the tax code. He supports undoing the 2017 Trump tax giveaway to the rich and ending the preferential tax treatment of their capital gains.

He has also come out in favor of eliminating the stepped-up basis loophole, a tax code provision that allows the rich to sidestep taxes on assets that have appreciated mightily over the years.

Other Biden proposals have the potential to shift who gets what as well. He’s pledging to “create a cabinet-level working group” that would within his first 100 days “deliver a plan to dramatically increase union density and address economic inequality.” And he endorses denying federal dollars to “employers who engage in union-busting activities, participate in wage theft, or violate labor law.”

Elizabeth Warren

On one level, the Massachusetts senator is telling an inequality story that the movers and shakers in Democratic Party circles over recent decades would find totally unobjectionable.

The nation needs to make the investments, Warren said in October, that give every kid in America “a chance to make it.” The wealthy just need to “pitch in” to help make that opportunity possible.

“I’m really shocked at the notion that anyone thinks I’m punitive,” she added. “Look, I don’t have a beef with billionaires.”

But plenty of billionaires have a beef with her. They see her signature tax proposal—an annual levy on personal fortunes worth over $50 million—as a slap against their success. Financial industry billionaire Ron Baron called Warren’s wealth tax proposal “pretty nuts” on CNBC’s Squawk Box. Starbucks billionaire Howard Schultz deemed it “ridiculous” on NPR’s Morning Edition.

“What’s ‘ridiculous,’” countered Warren, “is billionaires who think they can buy the presidency to keep the system rigged for themselves while opportunity slips away for everyone else.”

“We need to make,” she says on her Nation/IPS questionnaire, “big structural change to the economy.”

Warren’s wealth tax proposal—originally a 2 percent annual levy on household assets over $50 million, with a 3 percent rate over $1 billion—would certainly help restructure America’s wealth distribution. Economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman point out that David and Charles Koch held a combined fortune of $107.0 billion in 2018. If that proposed wealth tax had been in effect since 1982, the Kochs would have had to get by on a mere $37.8 billion.

In early November, Warren upped the wealth tax ante, raising her proposal’s top rate to 6 percent as part of her blueprint to fund Medicare for All.

Among the other Warren plans that would tap accumulated wealth: To finance expanded affordable housing programs, she would lower the threshold that triggers the federal estate tax from $22.8 million to $7.0 million and raise the estate tax rate to as much as 75 percent on bequest values over $1 billion.

Like Biden, Warren says she wants to sweep away the obstacles that make life miserable for workers hoping to organize. Unlike Biden, however, she’s also challenging the structure of corporate governance. Her Accountable Capitalism Act would require large corporations to become federally chartered and would empower workers to elect at least 40 percent of their boards of directors.

Bernie Sanders

The 2016 Sanders presidential campaign, many pundits now acknowledge, moved the Democratic Party’s mainstream to the left. What the conventional wisdom hasn’t yet realized: The party’s leftward shift has emboldened him to stake out ever more ambitious progressive territory.

We see that dynamic most clearly on the idea of annually taxing wealth, a notion that Sanders floated back in 1997. Now he has detailed his wealth tax vision in a plan that one-ups the initiative Warren announced this year. Under her revised plan, wealth over $1 billion would face a 6 percent annual tax. Under the Sanders plan, Americans with fortunes over $10 billion would face an 8 percent annual wealth tax levy.

America’s 400 richest people pay just 23.0 percent of their income in local, state, and federal taxes. The original Warren wealth tax, Saez and Zucman calculate, would nearly double that rate, to 45.9 percent. The Sanders proposal would more than triple it, to 74.8 percent.

On corporate governance, there’s the same Warren-Sanders two-step. He envisions workers taking 45 percent of corporate board seats, compared with her 40 percent. His Corporate Accountability and Democracy Plan would also move workers into ownership. Under the proposal, major corporations would have to transfer at least 2 percent of company stock to their workers every year until employees owned at least 20 percent of the corporate operation.

The latest Sanders economic justice initiative takes on the corporate pay practices that contribute so much to income inequality. In 1965, the Economic Policy Institute notes, top US CEOs took home 20 times the average worker’s pay in their industry. Last year, reports a new IPS study, 50 US CEOs took home more than 1,000 times their typical worker’s pay.

Thanks to the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, publicly traded corporations must now annually disclose their ratio of CEO to median worker pay. Sanders would place consequences on these disclosures: Corporations with CEOs making more than 50 times the typical worker’s pay, under his plan, would face higher corporate income tax rates. The wider their corporate pay gap, the steeper the tax. If this plan had been part of the tax code last year, Sanders writes in his Nation/IPS inequality questionnaire, Walmart would have paid up to $793.8 million more in taxes and JPMorgan Chase an additional $991.6 million. Sanders introduced legislation incorporating this pay-ratio tax plan November 13, with Elizabeth Warren a co-sponsor.

Pete Buttigieg

Last spring, the South Bend, Indiana, mayor was introducing himself as a pragmatic pol not afraid to take on wealth and power. In a New York Times interview he declared his support for a wealth tax and welcomed the idea of raising the top income tax rate from its current 37 percent to 49.9999 percent. (The Obama years ended with a top tax rate of 39.6 percent.)

In an interview with CNBC’s John Harwood in April, Buttigieg defended inconveniencing the rich. We shouldn’t pretend, he argued, “that you can make everybody better off while making nobody worse off.” Some people, he continued, “are not paying their share.”

These days, as he pivots to pick up the moderate voters abandoning Biden, “Mayor Pete” seems to be soft-pedaling positions that might brand him as any sort of class warrior. At the October candidate debate, he rushed away from an opportunity to explain his case for a wealth tax. And the Buttigieg campaign declined to respond to the Nation/IPS inequality survey.

His website mostly highlights now-standard Democratic anti-poverty prescriptions, from a $15 minimum hourly wage to increased federal funding for “schools with the highest economic and racial inequity.” The section on an “inclusive economy” focuses rather limitedly on knocking down “unfair barriers to entrepreneurship.” But under “organized labor,” his campaign still hints at broader inequality themes.

“Decades ago, we were promised a rising tide of economic growth that would lift all boats. We got the rising tide—GDP went up, productivity went up—but our paychecks didn’t show it,” the site reads. “Our economy has been tilted toward the wealthy and away from the middle and working class because the people in power designed our laws and policies that way.”

Kamala Harris

Mainstream commentators see the California senator taking an approach to narrowing inequality that avoids “the anti-Wall Street rhetoric” of Sanders and Warren, as Matt Stevens has written in The New York Times. Harris would narrow the gap “by significantly cutting taxes for low- and moderate-income households” instead of raising taxes on the nation’s wealthiest, Howard Gleckman of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center has added.

In fact, Harris’s proposals follow the basic Warren and Sanders playbook. They would tax the rich to pay for programs to boost the nation’s most vulnerable. Her boldest economic proposal, the Lift the Middle Class Act, would offer households making less than $60,000 annually as much as $6,000 in tax credits refunded monthly, with the money coming primarily from repealing the rich-friendly Trump tax cut.

The Harris version of Medicare for All would rest on much the same tax-the-rich moves the Sanders plan suggests. But she would limit her plan’s premium fee to households making over $100,000 a year. To fund a $315 billion plan to raise teacher salaries, she calls for strengthening the estate tax and cracking down on loopholes that let our wealthy avoid taxes on “estates worth multiple millions or billions.”

Harris is vowing to “flip the script and finally hold corporations accountable for pay inequality in America.” To narrow gender pay disparities, she says she wants to leverage the power of the public purse by requiring corporations to obtain an “equal pay certification” before they can gain lucrative government contracts.

Andrew Yang

Mainstream commentators have sometimes blamed the growing US economic divide on technological change. That explanation has proved less than compelling. If technology were driving inequality, analysts note, then America’s peers around the world ought to have experienced the same income chasms. But they haven’t.

Entrepreneur Andrew Yang has a new twist on the technological change theme. He sees a third of America’s workers losing their jobs to automation over the next 12 years. In response, he has proposed a Freedom Dividend, a $1,000 monthly check for every American age 18 or older.

The funding for this basic income initiative would come from a variety of sources, including two new taxes. The first is a European-style value-added tax, a levy on items collected at various points in the production and sale process. Economists typically consider VATs regressive because lower-income households spend a greater share of their income on consumer goods.

Yang’s second set of taxes would be far more progressive. His administration would kill the cap on income subject to the Social Security tax, implement a financial transaction tax, and end the favorable tax treatment of capital gains.

This year’s most discussed proposal for taxing the rich—an annual wealth tax—leaves Yang skeptical. In practice, he told CNBC’s Harwood, a wealth tax would have “massive” implementation and compliance problems.

Amy Klobuchar

The Klobuchar campaign has chosen a slogan—“Leading from the heartland”—that emphasizes down-home Midwestern political values. She promises to “pursue economic justice and shared prosperity” and begins her online biography by proudly noting her status as “the granddaughter of an iron ore miner.”

That iron ore miner probably supported Floyd Olson, the Depression-era Minnesota governor who at one point stood on the state Capitol’s steps and vowed to round up those who “happen to possess considerable wealth” but weren’t helping to fund relief for the state’s most desperate.

You won’t find many echoes of that militancy in anything that Klobuchar is proposing. Her platform stresses “ensuring all families have a fair shot in today’s economy” through “investing in quality child care, overhauling our country’s housing policy, raising the minimum wage, providing paid family leave, supporting small business owners and entrepreneurs, as well as helping Americans save for retirement.”

Klobuchar describes herself as enthusiastically pro-union and willing to take on “monopoly power.” Her approach to high incomes and concentrated wealth? She supports “at least” the 39.6 percent top marginal tax rate in effect before Trump took office. At the October primary debate, she said that a wealth tax “could work” and that she remains “open to it.”

Her administration, she adds in her 100 Days Plan, would move quickly to equalize tax rates for capital gains and ordinary income, ensure that incomes over $1 million face a minimum 30 percent tax, and close the carried interest loophole that lets fund managers sidestep billions of dollars in taxes.

Cory Booker

Apologists for our staggeringly unequal economic order often argue that the superrich turn greed into good through their charitable giving. A former Newark mayor turned US senator, Booker has a long history of hobnobbing with billionaire philanthropists—most famously with the wealthy drivers of school privatization.

That history couldn’t be more inconvenient for Booker’s 2020 candidacy, given the national furor over top-heavy philanthropy that Anand Giridharadas triggered with his 2018 book Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World. His book builds on the themes of an IPS report that explores the “increasing use of philanthropy as an extension of power and privilege protection.”

Booker is working to put his problematic past behind him with a campaign that accepts the Democratic primary contest’s most widely shared progressive economic planks, from a $15 minimum hourly wage to a tougher-on-the-rich estate tax. He says he wants the revenue from a new estate tax and from plugging the step-up loophole for inherited capital to go toward funding an ambitious national “baby bond” program.

This initiative would establish a savings account—accessible at age 18—for every newborn. The federal government would deposit $1,000 into these accounts at birth and add up to $2,000 a year after that, depending on family income. Kids from the poorest families would have a nest egg close to $50,000 by the time they hit adulthood.

Tulsi Gabbard

The widespread attention this member of Congress from Hawaii has received for her foreign policy positions has tended to overshadow her across-the-board support for many of the egalitarian policy prescriptions her primary rivals have advanced.

Gabbard supports eliminating tax breaks for corporations that shift profits abroad and a national $15 hourly minimum wage. She says she wants to “ensure Social Security’s solvency by taking the trillions of tax dollars now spent on military spending and tax giveaways to the wealthiest American families and corporations and reinvesting them” in the Social Security program.

“The profound income and wealth inequality in America,” she wrote on Twitter, “tears at the fabric of who we are as a nation.”

Julián Castro

From deep in the heart of Texas, Castro has followed an impeccably traditional route to political stardom: Harvard Law, a big-city mayor’s office, a federal cabinet position. Unfortunately for him, a few awkward debate moments have pundits writing him off as a serious candidate. But Castro, like Harris, has some serious egalitarian ideas that deserve attention—and demonstrate again how deeply inequality concerns have penetrated the Democratic Party mainstream.

“The fundamental economic challenge of our time,” Castro’s campaign proclaims, “is to reverse widening inequality and lift up working families.”

His People First Economic Plan for Working Families, unveiled in August, attempts to do both, in part by changing how the nation treats the transgenerational shifting of wealth. The current approach taxes the estates the wealthy leave behind at death. Progressive analysts have suggested an alternative: taxing the windfalls that wealthy people inherit as ordinary income. Castro takes this approach. His proposed tax on inheritances of $2 million or more would raise an estimated $250 billion over 10 years.

Castro would also target the annual untaxed gains the wealthy realize on the value of their assets. Deep pockets currently pay tax on their investing profits only when they sell assets. Under the mark-to-market approach that Castro favors, owners of assets that gain in annual value would pay tax on those gains.

Workers have their labor income taxed at the end of every year, and “multi-millionaires and billionaires who rely primarily on investment income” should have the same obligation, he said in an August statement.

Revenue from these and other tax changes, under the Castro plan, would fund universal child care and a major expansion of the earned income tax credit for struggling households.

Tom Steyer

The richest Democrat in the 2020 race so far, billionaire Tom Steyer is making points Americans seldom hear the richest among us make.

“The top 0.1 percent—people like me—have amassed nearly as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent of Americans,” Steyer wrote in October. “As some 43 percent of American households struggle to pay for basic monthly expenses, it’s undeniable that this is an unfair system…. And it’s only getting worse under Trump, who has worked with Republicans in Congress to open up even more loopholes for himself and others at the top.”

Steyer supports a higher estate tax and a 1 percent annual wealth tax on the nation’s richest 0.1 percent, essentially those worth over $20 million. As part of his People Over Profits Economic Agenda, he’s pushing for a $15 national minimum hourly wage, a repeal of the Trump tax cuts, and two years of free public college.

The billionaire styles himself as “a progressive and a capitalist” who understands that “unchecked capitalism produces market failures and economic inequities.” He shelled out over $10 million on TV and online ads in his campaign’s first month, outspending all his rivals. But his early ads have been more biographical than programmatic.

Whether that changes—and whether Steyer starts to stress his class-traitor perspective on the system that made him rich—will likely determine whether his candidacy proves to be more than a rich man’s idiosyncratic political fling.

Marianne Williamson

Political analysts and policy wonks almost universally dismiss the candidacy of spiritual leader Williamson as a spaced-out sideshow. But she doesn’t deserve that contempt. Her Nation/IPS questionnaire responses show a candidate grappling with a staggeringly unequal status quo.

Williamson supports a wealth tax and a return to a 70 percent top-bracket income tax. She said she wants to “make it illegal for CEOs to be paid with stock options,” considers herself “the first presidential candidate to advocate for reparations” for slavery, and believes “strong unions make America strong by reducing wealth inequality.”

Joe Sestak

A former admiral and a Pennsylvania congressman, Sestak has made ending corporate welfare one of his signature issues, and his questionnaire answers evince a deep disappointment with the wide gaps that divide corporate CEO and worker pay. Sestak says he wants to end the preferential tax treatment of capital gains and supports the elimination of the step-up loophole that lets the affluent transfer appreciated stock and other assets to their heirs without ever incurring a capital gains tax.

Michael Bennet

The Colorado senator told a New Hampshire audience in October that he has the “capabilities to push back on someone who needs to be pushed back on.” Yet those who need to be pushed, in his supercentrist worldview, don’t appear to be the holders of ample private fortunes. Bennet’s policy prescriptions include nothing that would more than slightly inconvenience the nation’s rich. He has a Plan to Reward Hard Work but can’t even bring himself to support a national $15 hourly minimum wage.

Steve Bullock

In his one and only debate performance, the Montana governor tried to make the case that he could win Trump voters without the “wish list economics” of programs like Medicare for All. His “fair shot agenda” calls for expanding labor protections but goes light on tax policy specifics.

“Steve will ensure our tax code promotes economic growth for all,” his website promises, “while encouraging investment in employees and infrastructure—not just stock buy-backs.”

Does this mean that the tax code should continue to countenance stock buy-backs—an executive maneuver that artificially jacks up share prices, as well as the executive compensation keyed to them?

John Delaney

In the Democratic primary race, the former congressman from Maryland has emerged as the comic relief, a rich businessman tromping through every county of Iowa, spending down his personal fortune while making zero progress in the polls.

But his candidacy may carry an important political lesson: What Delaney is selling—a tone-deaf take that largely ignores the dangers posed by concentrated wealth—hasn’t been finding many buyers among primary voters.

A quarter century ago, New York University economist Edward Wolff pitched Bill Bradley, then a Democratic senator from New Jersey with presidential ambitions and a reputation for bold thinking, on a wealth tax. Households with over $1 million in net worth, under Wolff’s plan, would face a 0.3 percent annual levy on their assets.

Bradley seemed enthusiastic about the idea at first, Wolff told The New Yorker early this year, but later walked away from it. The senator thought that a wealth tax would be politically dangerous, calling it “dynamite.”

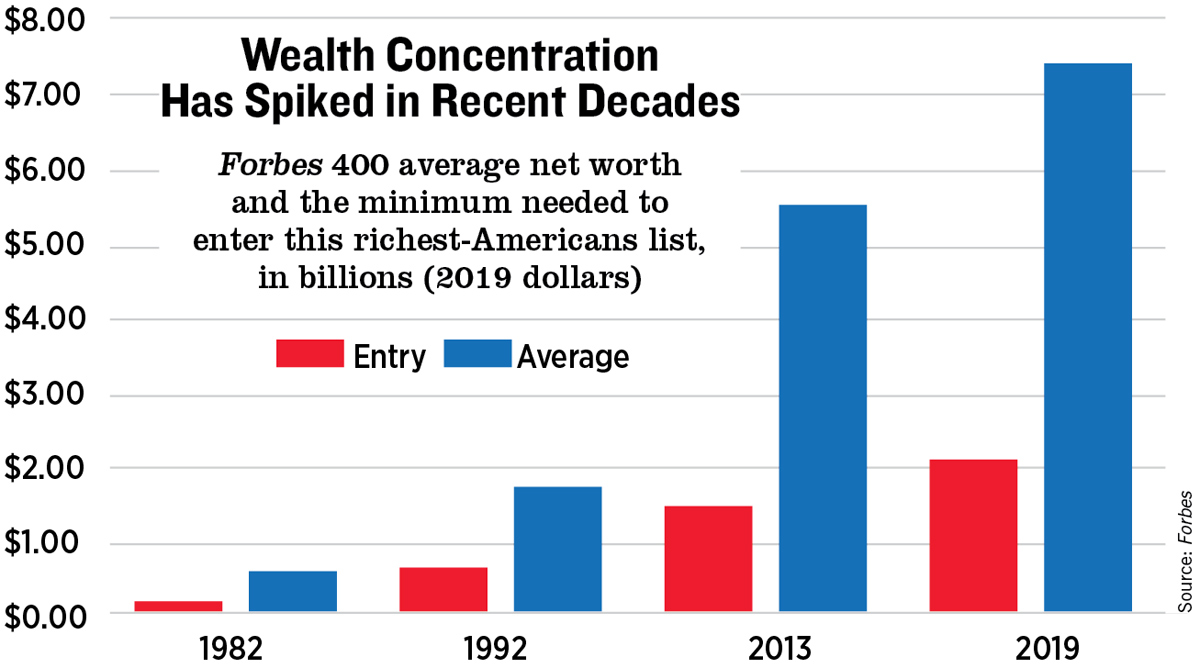

Today, a generation later, two of the top three Democratic presidential contenders are seeking a wealth tax 20 times as aggressive as the plan Bradley considered too toxic.

Even more remarkable: Most of the other Democratic candidates are backing at least a significant part of the inequality-fighting agenda that Sanders and Warren share. The rich, it seems, may have finally lost their political immunity.