AVENGING ANGELS

AVENGING ANGELS

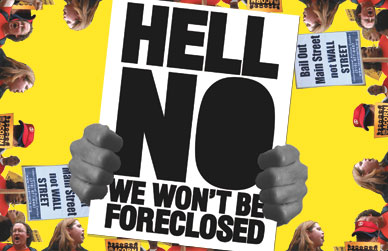

“This is a crowd that won’t scatter,” James Steele wrote in the pages of The Nation some seventy-five years ago. Early one morning in July 1933, the police had evicted John Sparanga and his family from a home on Cleveland’s east side. Sparanga had lost his job and fallen behind on mortgage payments. The bank had foreclosed. A grassroots “home defense” organization, which had managed to forestall the eviction on three occasions, put out the call, and 10,000 people–mainly working-class immigrants from Southern and Central Europe–soon gathered, withstanding wave after wave of police tear gas, clubbings and bullets, “vowing not to leave until John Sparanga [was] back in his home.”

“The small home-owners of the United States are organizing,” Steele concluded, “tardily perhaps, but none the less surely.” It wasn’t just homeowners–three months earlier the governor of Iowa had called out the National Guard after farmers stormed a courthouse and threatened to hang the judge if he didn’t stop issuing foreclosures. They left him in a ditch, bruised but alive. By the end of the 1930s, farmers’ and home-owners’ struggles had pushed the legislatures of no fewer than twenty-seven states to pass moratoriums on foreclosures.

The crowds appear to be gathering again–far more quietly this time but hardly tentatively. Community-based movements to halt the flood of foreclosures have been building across the country. They turned out in Cleveland once again in October, when a coalition of grassroots housing groups rallied outside the Cuyahoga County courthouse, calling for a foreclosure freeze and constructing a mock graveyard of Styrofoam headstones bearing the names of local communities decimated by the housing crisis. (They did not, unfortunately, stop the more than 1,000 foreclosure filings in the county the following month.) In Boston the Neighborhood Assistance Corporation of America began protesting in front of Countrywide Financial offices in October 2007. Within weeks, Countrywide had agreed to work with the group to renegotiate loans. In Philadelphia ACORN and other community organizations helped to pressure the city council to order the county sheriff to halt foreclosure auctions this past March. Philadelphia has since implemented a program mandating “conciliation conferences” between defaulting homeowners and lenders. ACORN organizers say the program has a 78 percent success rate at keeping people in their homes. One activist group in Miami has taken a more direct approach to the crisis, housing homeless families in abandoned bank-owned homes without waiting for government permission.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

It’s unlikely, though, that any of these activists will be able to relax soon. Other than calling for a ninety-day freeze on foreclosures–which, given that loan negotiations can take many months to work out, would almost certainly be inadequate–President Obama has been consistently vague about his plans to address the foreclosure crisis. He has indicated his support for a $24 billion program proposed in November by FDIC chair Sheila Bair, which would offer banks incentives to renegotiate loans, aiming to reduce mortgage payments to 31 percent of homeowners’ monthly income. Obama’s economic team has since worked with House Financial Services Committee chair Barney Frank on a bill that would require that between $40 billion and $100 billion of what’s left in the bailout package be spent on an unspecified foreclosure mitigation program. It would be left to Obama’s Treasury Department to design that program. But Frank’s and Bair’s proposed plans are voluntary. Banks that choose not to accept federal assistance won’t have to renegotiate a single loan.

Community organizers, however, aren’t sitting around waiting for banks to come to the table. Nowhere have they had more cause to keep busy than in California, home to a quarter of the 3.2 million foreclosures filed in the country last year. The collapse of the state’s hyperinflated real estate market has left as many as 27 percent of mortgage holders owing more on their homes than the properties are worth; California’s foreclosure rate is more than twice the national average. From San Diego to Stockton, in churches, union halls and community centers, angry homeowners have been organizing to freeze foreclosures and impose a systematic modification of home loans.

The crisis has produced some unlikely activists. Faith Bautista didn’t start out as a rabble-rouser. A small, energetic and stubbornly cheerful woman, she has run a tiny nonprofit called the Mabuhay Alliance since 2004. Until recently, it functioned as an all-purpose minority small-business association. With a staff of six working out of a mini-mall office behind an auto parts store in an industrial section of San Diego, the Mabuhay Alliance served a largely Filipino community (mabuhay translates roughly from Tagalog as viva!) offering, among other services, free income-tax preparation, microloans and counseling for first-time homeowners.

It was through the latter program that Bautista heard the first rumblings of the mortgage meltdown, which would ultimately bring down Wall Street’s most powerful financial firms. Southern California’s development boom hadn’t yet begun to ebb in late 2006, but, Bautista says, “people were already calling us and asking what was going to happen. They were clearly going to default.”

The community Mabuhay serves–about 40 percent Filipino, the remainder Latino, African-American and other Asians–was hit particularly hard. Throughout the housing boom, immigrant and minority borrowers were disproportionately issued high-priced subprime loans, even when they qualified for less expensive, fixed-rate mortgages. One study by the California Reinvestment Coalition found that African-American and Latino borrowers were nearly four times as likely as whites to receive high-cost mortgages. Bautista had an adjustable-rate mortgage on the home she bought in 2004. Her monthly payments soon leapt to $6,000. It took her nine months, she says, and a personal meeting with the CEO of the bank that held her mortgage, to renegotiate the loan. It quickly became obvious to her that fighting the banks on an individual basis would be inadequate to the scale of the crisis–only an organized battle for systematic changes would help keep people in their homes.

In the early months of 2007, as the first of the subprime lenders began to declare bankruptcy, Bautista started contacting major lenders, asking them to stop foreclosures and take part in a “massive loan-modification program”–dropping interest rates, writing down principals and donating executive bonuses to a fund for borrowers at risk of default. If lenders shared responsibility for the crisis, she calculated, homeowners shouldn’t bear the full brunt of the suffering. Not surprisingly, she laughs, “they didn’t want to talk to us.”

That summer, with the help of the Greenlining Institute, a Berkeley-based research and advocacy group that works on racial equality issues, she was able to arrange a meeting with Countrywide co-founder and CEO Angelo Mozilo. At the time, almost one-fourth of Countrywide’s subprime loans were delinquent. The meeting, Bautista says, was fruitless: “Eyes are closed, ears are closed.” Over the next few months, she met three more times with Countrywide management, getting nowhere. “They didn’t want to admit they were doing anything wrong.”

Elected officials appeared equally blind to the extent of the problem. Countrywide’s stock had plummeted, but the influence of the nation’s largest mortgage lender still ran deep. Mozilo’s so-called Friends of Angelo program had cut favorable deals on loans to his highly placed acquaintances, including Christopher Dodd and Kent Conrad, chairs of the Senate banking and budget committees, respectively. And Countrywide, along with other top mortgage lenders and industry associations, spent tens of millions of dollars lobbying Congress and gave millions more in campaign contributions. By mid-October 2007, the government’s only response to the foreclosure crisis had been the creation of the Hope Now alliance, a voluntary mortgage-industry coalition that established a telephone hot line to aid homeowners in altering the terms of their mortgages. But, critics say, the program has done little more than design repayment plans that in many cases actually increased borrowers’ monthly payments. “I call it Hope Not,” quips Bautista.

At the state level, things weren’t much better. Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger brokered a nonbinding agreement in which Countrywide and other lenders volunteered to extend the introductory low interest rates on some adjustable-rate mortgages. It only deferred disaster and did nothing for those who were already in default. Meanwhile, new foreclosure records were being broken every month.

The day before Thanksgiving, the Mabuhay Alliance, joined by the Mexican-American Political Alliance, staged a protest in front of Countrywide’s San Diego office. They attempted to hand-deliver a turkey to Mozilo, who, not counting stock options, would be paid $22 million in 2007, down from $42 million in 2006. Once again, the doors were locked. Only about fifty people showed up that day, but the protest got enough press to have a powerful symbolic effect. “No one was willing to take on Mozilo in California,” says Greenlining’s Robert Gnaizda. “He held enormous power. And [Bautista] took him on. She forced the financial industry to pay attention.”

The next week, Bautista and Gnaizda went to Washington and met with Federal Reserve chief Ben Bernanke and FDIC chair Sheila Bair, asking for a freeze on foreclosures and wholesale relief for mortgage holders. Bair was receptive, Bautista says. Bernanke was not. Eight months later, when the FDIC took over IndyMac, Bair immediately suspended foreclosures. “Now they’re willing to do it,” Bautista shrugs. If they’d acted earlier, she says, “all those people who were foreclosed wouldn’t have been foreclosed.”

In December, a few weeks after the Countrywide protest, she and Gnaizda wangled a meeting with California Attorney General Jerry Brown, asking him to sue Countrywide for defrauding borrowers. He wasn’t interested, Bautista says. The following June, a few days before Bank of America bought out the crippled lender, Brown finally filed suit against Mozilo and Countrywide. Gnaizda explains the delay: “Countrywide was not weak in December.”

In the meantime, all the major loan providers in the country have agreed to work with Mabuhay to modify individual loans. This means, Bautista says, that Mabuhay can help about twenty people a week. She is far from satisfied. Despite the hundreds of billions of dollars given to the financial industry, no federal or state government has provided any substantive relief to the people hit the hardest by the mortgage crisis–the ones who are losing their homes. “You gotta start from the bottom and go up,” Bautista says. “If you start at the top, then at the bottom you get crumbs. You get nothing.”

In December Mabuhay sponsored a “foreclosure clinic” at a community college in the San Francisco Bay Area city of Vallejo, which despite its small size–its population is about 112,000–boasted the tenth-highest foreclosure rate in the country at the time. About 150 anxious homeowners showed up, clutching thick folders of financial documents, waiting to speak with mortgage counselors. Their stories were painfully similar: one couple was struggling to pay an interest rate of 16 percent; another was unable to make $4,300 monthly payments and owed $630,000 on a home worth $370,000; another, in their mid-60s, had resigned themselves to losing the home in which they’d lived for twenty-three years and spending their retirement in a motor home.

Standing beside Bautista at the front of the auditorium, Gnaizda did his best to channel the crowd’s frustration into action. “Ten million families are facing foreclosure right now,” he said. “Change is not going to come about because President Obama wants it to. He is not going to act unless you hold his feet to the fire.”

Gnaizda was not alone in that conclusion: other grassroots efforts to stop foreclosures have been sprouting up all over California. In metropolitan Los Angeles and Oakland, groups like ACORN had already established an effective infrastructure to organize low-income homeowners. A list of community demands that came out of a December 2007 ACORN-sponsored meeting at an Oakland senior center became the basis for a July state law requiring banks to warn homeowners thirty days before filing a notice of default. The law is credited with dramatically lowering foreclosure rates in California for two months after it took effect. (Predictably, foreclosure rates resumed their northward climb after that.)

More recently, ACORN has been pushing the adoption of the program the group helped pioneer in Philadelphia, a mandatory mediation process that forces lenders to negotiate with homeowners before filing a judgment of default. “If they can’t figure this out in Sacramento,” says ACORN’s Austin King, “they’re not trying.”

Much of the local organizing on the issue, though, has not come from the usual activist suspects. Circumstances have forced groups that usually practice more staid forms of engagement into the fray, particularly in the former industrial towns just beyond the urban fringe, which have been among those hit hardest by the economic collapse. The antiforeclosure movement in Antioch, about thirty-five miles east of Vallejo, began with ten people forming an organizing committee at a local Catholic church. “We just heard dozens and dozens of stories of people struggling to keep their homes, of people losing their homes. They couldn’t get any of the banks to respond or even speak to them,” says Adam Kruggel, executive director of Contra Costa Interfaith Supporting Community Organization (CCISCO). Two hundred and fifty people showed up at the group’s first meeting on the issue. “We sort of deputized ourselves,” Kruggel says. “The government wasn’t regulating the banks, so we were going to embarrass them in public.”

The strategy worked. CCISCO protested in front of several Antioch bank branches in May. Lenders soon began returning the group’s phone calls and agreeing to renegotiate their members’ loans. But the Bush administration’s bailout plan generated enough anger that, Kruggel says, “we realized we needed to work on a local and national level. For less than what [the Treasury] gave Wells Fargo, they could create a loan-modification program that could save a million and a half families their homes.” CCISCO began coordinating with similar efforts one county over in Stockton and halfway across the country in Kansas City, and the group sent a lobbying delegation to Washington. It’s asking for a six-month freeze on foreclosures and a cap on mortgage payments at 34 percent of family income. “Any bank that got any bailout money needs to do systematic loan modifications,” Kruggel says. “We’re not going to wait for the Obama administration.”

Craig Robbins, who directs ACORN’s foreclosure campaign, echoes Kruggel’s sentiment: “We’re excited about some of the things Obama has been saying, but there’s got to be tremendous pressure for a real, comprehensive federal solution.” Taking cues from Depression-era antiforeclosure movements, ACORN activists began disrupting foreclosure sales at courthouses across the country in Januaary. “We’re looking to throw a wrench in the foreclosure machinery,” says Robbins, adding that ACORN is planning to organize “rapid defense teams” ready to turn out crowds on short notice to prevent evictions. Until that happens, it might help to remember that the crowd of thousands that came to the Sparanga family’s defense in Cleveland didn’t gather until four years into the Depression. This one has just begun.