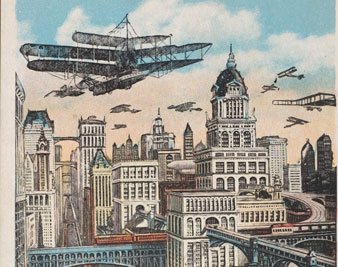

WALKER EVANS ARCHIVE/THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NYCA postcard from the Walker Evans Archive

WALKER EVANS ARCHIVE/THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, NYCA postcard from the Walker Evans Archive

For nearly sixty years of his life, Walker Evans collected picture postcards. An exhibit of that collection, which by the time of Evans’s death in 1975 totaled some 9,000 items, is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City through May 25. In a telling gesture, a vitrine near the exhibit’s entrance houses objects from Evans’s other collections–bottle caps, beer tabs, driftwood, road signs–as well as postcard storage boxes and dividers with labels like “Street Scenes,” “Summer Hotels,” “Fancy Architecture,” “Railroad Stations,” “Monuments,” “Bridges” and “Curiosities.” Such categories could well classify Evans’s own photographs, from the stark, magisterial black-and-white pictures he took while working with the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression to the haunting color images that he made with a Polaroid SX-70 Land Camera in the last years of his life. Evans is widely touted as having fully refined the documentary style of photography, a “styleless” or “artless” style that married simplicity of composition, devotion to the life of the vernacular and social awareness.

While the postcards clearly resonate with Evans’s photography, it’s worth asking whether the collection should be understood not as an archive of source texts but as an artistic project in its own right. After all, Evans’s first contact with the Museum of Modern Art, the institution that would vault him to wide esteem in the art world, was a project undertaken in 1936 featuring photographic images printed by Evans in the dimensions of postcards. (Examples of these small prints are on view at the Met; the project was abandoned in 1938.) A decade on, newly installed at Fortune as “special photographic editor,” Evans turned his first picture story into a portfolio of postcards from his collection. An unsigned response to the piece noted, “His selections are manifestly neither a gag nor a fad nor an amusing hobby; they perform exactly the same function as his photographs.”

Evans’s devotion to, and obsession with, indigenous forms, and his developing taste for vernacular objects worth collecting, were points of fierce pride. Friends and acquaintances sent Evans postcards in hopes theirs might be inducted into the rarefied lot of his collection, while his counterparts in the art and publishing world humored his interests, publishing several postcard-based photo essays and inviting him to lecture on the subject. To all suitors and facilitators Evans tended to play the part of the evangelist, arguing that the postcards were more than ephemera of an age gone by. Their very ordinariness was, to him, critical to their significance in telling the story of the United States. He was always at pains to prove that his interest in these documents wasn’t comedic or, worse, ironic. People did indeed appreciate the postcards, mostly because of the aura of the collector. This was a disappointment. Evans intended his collection to be more than an interesting tidbit; to him, it was an object lesson. The postcards exhibited a profound vision of American life, one he perhaps thought even superior to his own.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Who collects, and why? Along with the completists are those collectors just as happy to hunt and gather on the margins of a genre. There are collectors obsessed with calculating the value of an object according to an economics of scarcity and those obsessed only with the value they ascribe to their objects. There are collectors whose aim is the preservation of history for posterity, and those whose aim is purely autobiographical. Few collectors simply accumulate. Always there is an underlying principle, be it obsessive, altruistic or economic. This determines which genre of vinyl records, what vintage of comic book, which brand of electric guitar, what era of books and which sort of postcards are sought and treasured the most.

Born in 1903, Evans came of age as a boom in American travel coincided with an explosion in the picture postcard business. Away from home, Americans kept in touch with loved ones and recorded their unprecedented journeys to distant towns and cities. In 1903 the US Postal Service processed 700 million postcards. They cost only a penny to mail, and following a change in the postal code in 1907, half of a postcard’s blank side was for correspondence and the other half for the address. (Taken by amateurs, the postcards were printed and hand-colored, mostly in Germany.) Some older cards have even briefer messages scrawled right on the pictures. Evans loved such anomalies: one card on display at the Met reads, “Drug store where I am now working,” with an arrow pointing to the shop.

Evans began collecting during his teens, purchasing cards as mementos of family trips. He bought new cards at Kresge’s and Woolworths but also looked for older examples, raiding the cards kept by family and friends. While the size of Evans’s collection is impressive for a lifetime, it is hardly astronomical, and if you consider that 9,000 cards amount to an average of 150 per year, or just three per week, it seems modest indeed. Evans could have amassed ten times as many cards, but he treated his collection as something more than an agglomeration. Evans was a connoisseur, not just of the various types of cards, or of cards from selected decades, but of a card’s composition, color and mood. Evans didn’t desire just any postcard–because just any postcard wouldn’t express the variety of elements he wanted his collection to breathe. His was a curated selection of objects, one with intention, personality and purpose.

The Met exhibit, which features around 750 cards, encompasses just a few rooms, yet it feels quite expansive. Upon entering, one sees a giant grid of more than 200 “street scene” postcards. Nearby is a vitrine with Evans’s other collections and a spinner-rack display of beach scenes. Deeper in, smaller but still dauntingly jampacked grids of cards featuring factories, disasters and more present themselves along the walls. Interspersed are cases containing Evans’s magazine articles about postcards and the actual cards reproduced therein. Finally, there are several examples of Evans’s own images in postcard size, which illustrate strongly his debt to the aesthetics of his collecting, and his glee in matching the “styleless” style of the postcards with his camera eye.

The beach scenes in the first room have few crashing waves and dramatic sunsets; mainly there are throngs of well-covered beachgoers and a lot of municipal buildings. One is simply a woman cowering beneath an umbrella. Her face cannot be made out.

The street scenes are mostly Mains and Fronts, alphabetical by state. They are uniformly mundane views, often poorly composed. The photographers ended up chopping off a steeple here, half a family there. On many, the image is almost entirely composed of the road itself, paved or unpaved. Buildings and cars peek in, often from behind trees, but the prime visual real estate is the street.

Factories belching smoke. Hideous resort hotels. Strangely shaped lighthouses. An image of the Holland Tunnel with oddly static-looking cars, plastic-looking drivers and passengers. An image of the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel with no cars at all; it’s just the inside of a tunnel.

The most common phrases on the cards are “a glimpse of…,” “birds eye view of…” or “looking from….” Then the cards have quick notes telling which room the sender occupies in the pictured resort, lamenting the inability of the recipient to come join the vacationer, or making jokes. In the Met gallery, one-liners drifted over the hum and buzz of the crowd, much like the brief messages scrawled across some of the images.

“That’s near Chicago.”

“Someone gave me a bunch like this.”

“What a bizarre scene.”

“That building is still there.”

“God in heaven, that’s what it looked like.”

I got pretty excited when I found a few postcards showing my hometown too.

In his introduction to the exhibition catalog, curator Jeff Rosenheim writes, “A surprising number of highly accomplished writers, picture makers, and performers are obsessive collectors.” He then speaks of Nabokov, Degas, Warhol and others. Of more recent collector-artists, Martin Parr and Richard Prince have received perhaps as much esteem for their canny collections of postcards (Parr) and trashy dime-store novels and Beat ephemera (Prince) as for their fine-art production, a development that would have thrilled Evans. Rosenheim denotes the reasons behind such collections: “pleasure and instruction, to recover their lost youth, to build archives of material upon which to construct their own personas…source material for their art…a distraction from the burden of creation.” The notion of the artist as collector, and of the collection as artwork, has matured significantly since Evans’s time.

Yet in his time it was a rather marginal idea that a collection, especially of something as banal as picture postcards, could relay any deep meaning or significance. “I think artists are collectors figuratively,” Evans once said. “I’ve noticed that my eye collects.” His work conveyed a reverence for anonymity and mass production, yet the anonymous, mass-produced items he so cherished as indigenous expressions of American life were seen as mere curios of a bygone age. He frequently extolled such average stuff as office furniture and common hand tools in his columns for Fortune and Architectural Forum. He kept lists of hoped-for concepts for pieces that never made it into the magazines but are telling nonetheless: “Ocean liners to be scrapped,” “Roadside Motels,” “Post Offices,” “Freight Car Signs,” “Jail.”

In a 1964 lecture at Yale University, a transcript of which is included in the exhibition catalog, Evans laid out his most compelling argument for the postcard collection as art. He referred to his own photographic style as the “lyric documentary” and compared it to the works of Henry James, Eugene Atget and to the postcards. This style was contrasted with the “decadent lyric,” the rather more artificial, aesthetically overwrought style of his photographic forebear, Alfred Stieglitz. He told his audience at Yale: “The real thing I’m talking about has purity and a certain severity, rigor, simplicity, directness, clarity, and it is without artistic pretension in a self-conscious sense of the word. That’s the base of it: they’re hard and firm.” Elsewhere he warned against thoughts of straight nostalgia (“‘Good old times’ is a cliché of the doddering mind”), while lamenting the modern postcard, which he had called the “quintessence of gimcrack…gaudy boasts that such and such a person visited such and such a place, and for some reason had a fine time.” “Gone is all feeling for the actual appearance of street,” he insisted, “of lived architecture, or of human mien.”

Yet while narrating a slide show that concluded the lecture, Evans lost the ability to convey his angle: “I haven’t got much to say about that except you just probably feel as I do…” and “That’s a document, and of course it’s gained a great deal in time.” It is the push and pull of the public and private at work. Reading these rhapsodic lines and seeing the cards–street scenes, men gambling, rail yards–one senses his difficulty putting forth to an audience of strangers what had taken him a lifetime to hone. At one point he admitted, “You have to spend much too much time going through junk to pick out ones that appeal to you that have this style that I care about.” To Evans the import of the images, the brilliance of composition and the wonder of their dull beauty is self-evident and moreover deeply personal, perhaps beyond telling, yet the urge to share drives the whole enterprise. Taking in these images at the Met is something like looking into the artist’s eye, the eye that collects, and gaining a profound comprehension of what that eye was always seeking.