UNC PRESSA cartoon from Puck magazine, 1897

UNC PRESSA cartoon from Puck magazine, 1897

Three days before Christmas in 1946, Havana’s Hotel Nacional was closed for a private meeting. Armed guards blocked entry to its lovely grounds atop a seaside bluff in the plush El Vedado district. Inside the stately cream-colored Art Deco hotel, a group of distinguished foreign visitors tucked into a feast of local delicacies. There were crab and queen conch enchiladas from the southern archipelago; swordfish and oysters from the nearby village of Cojímar; roast breast of flamingo and tortoise stew; grilled manatee, washed down with añejo rum. It is unknown whether the attendees–whose number included about twenty of North America’s most notorious gangsters–ended their meal with a cake like the one served at their feast’s fictional rendering in The Godfather Part II. But as in the film, the purpose of the gathering was clear: to divvy up shares in the empire of vice they were busy establishing in Havana.

During the next decade, the mafia built a seaside gambling resort, which soon rivaled in profits and glamour its sister project in dusty Las Vegas. Under the canny direction of Meyer Lansky, the Jewish don who’d risen from the streets of New York’s Lower East Side, members of the Havana Mob became fabulously wealthy. So too did Cuba’s US-backed dictator, Fulgencio Batista, whose stake in the mob’s affairs exceeded the sacks of cash delivered weekly to the presidential palace. With Lansky and fellow mobsters like Santo Trafficante employed as “tourism experts” in his government, Batista eliminated taxes on the tourism industry, guaranteed public financing for hotel construction and–as T.J. English shows in Havana Nocturne, an exacting and lively account of the era–even granted responsibility for Cuba’s infrastructure development to a new mob-controlled bank, BANDES. In December 1957 the opening of the Riviera, a $14 million mafia show palace just down the seawall from the Nacional, was celebrated by a special episode of The Steve Allen Show on US television and a gala in Havana featuring Ginger Rogers. Three months later, the twenty-five-story Havana Hilton–mortgage holder: BANDES–became Cuba’s biggest hotel yet.

The party ended on New Year’s 1959, when Batista fled the island as Fidel Castro’s barbudos advanced on its capital. Castro and his bearded rebels established their headquarters in the Havana Hilton and loosed a truckload of pigs on the sleek lobby of the Riviera. Castro announced the “socialist nature” of his revolution. Nikita Khrushchev sent Soviet missiles. President John F. Kennedy–who, during a visit to Havana the previous year as a senator, had spent an afternoon with three mob-supplied prostitutes under the gaze, from behind a two-way hotel-room mirror, of Santo Trafficante–instituted the embargo that defines US-Cuba relations to this day.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

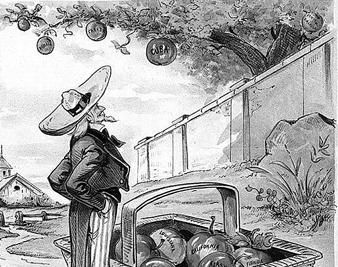

“I couldn’t get that little island off of my mind,” Lansky remarked after his first visit to Cuba in the 1920s. The gangster was no less covetous of Cuba, and proved no less fixated on controlling it, than a series of US presidents reaching back to the founders. “I have ever looked on Cuba,” wrote Thomas Jefferson to President James Monroe when the United States gained control of the Florida peninsula in 1821, “as the most interesting addition which could ever be made to our system of States.” Monroe’s secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, was more blunt. “The annexation of Cuba to our federal republic,” he wrote, “will be indispensable to the continuance and integrity of the Union itself.” After the United States took possession of Texas and California by war in 1848, many in Washington advocated annexing Cuba by force as well. The impulse was quashed for a time. Nevertheless, with Spain’s empire sunk in a long decline, the United States’ eventual possession of Cuba was viewed as inevitable for most of the nineteenth century. In a political cartoon from 1897, one of a trove of such images Louis A. Pérez Jr. uses to illustrate his brilliant book Cuba in the American Imagination, Uncle Sam stands beneath a fruit tree with a basket of plums, each bearing the name of a foreign territory already attained–Louisiana, Florida, Texas. From an upper branch hangs a “Cuba” plum, upon which Sam gazes keenly, his look distilling the common view: if America refrained from picking Cuba with a forceful hand, the ripe prize would eventually fall to its basket simply by dint of geography and time.

When the warship USS Maine mysteriously exploded while docked at Spanish Havana in February 1898, the United States had a pretext for shaking the tree of its remaining fruit. A few months later, Cuban rebels and invading US forces expelled Spain from the island, and Cuba (along with Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines) was annexed to the United States. “We went to war for civilization and humanity,” President William McKinley eulogized, “to relieve our oppressed neighbors in Cuba.” Humanity’s gains were hazy, but what the United States certainly gained from the war was an empire. Puerto Rico and the Philippines became de facto American colonies; and with the passage of the Platt Amendment in 1901, Washington arrogated to itself the right to intervene in Cuba’s affairs whenever it wished–providing also for the seizure of Cuban territory at Guantánamo Bay to establish a US naval base purposed “to enable the United States to maintain the independence of Cuba” (and conveniently positioned to protect what would soon be a key sea lane to the Panama Canal).

Gaining control of Cuba fulfilled a long-sought strategic aim. But equally important for the United States was how the invasion of Cuba came to shape its foreign policy and self-image at large. The Spanish-American War–the Union’s first large-scale military campaign since Reconstruction–bolstered American unity and inaugurated America’s self-conception as a “universal nation” endowed with the moral mission of projecting its power abroad. Before 1898, as Pérez stresses, quoting the historian Norman Graebner, “the foreign policies of the United States were rendered solvent by ample power to cover limited, largely hemispheric, goals.” Afterward, those policies became global, their stated aims–universal democracy and freedom for all humanity–abstract in nature and unobtainable in practice. As Pérez writes, the template for US foreign wars, up to the “war on terror,” with its crusading aim to “rid the world of evil,” was cast in America’s war for Cuba.

The argument that the Spanish-American War was a watershed in the United States’ fashioning of its national identity isn’t new. The value of Pérez’s study–the latest in a series of perceptive books on US-Cuba relations by this prolific historian–is to illustrate how an avid US self-interest was transformed into selfless moral enactment. While Cuba in the American Imagination is hampered by confusing chronology, Pérez shows clearly how in the late nineteenth century politicians in the United States and their allies in the press employed language–and a series of figurative metaphors specifically–to nurture in Americans’ minds a conception of Cuba as object and stage for fulfilling the United States’ imperial destiny. Early on, there was the image of Cuba as ripening fruit that would “naturally” and inevitably one day be Uncle Sam’s. Later came references to Cuba as “our Armenia,” implying that the United States, by defending Cuba’s rebels against Madrid’s repression, could prove its humanitarian mettle where Europe’s nations had failed to prevent the recent Armenian genocide at their door. And finally, as invasion approached, there were invocations of Cuba as a virtuous lady whose protection against Spain’s depredations was a test of American manhood.

This last figure was yanked out of the political funny pages and foisted upon Evangelina Cossío Cisneros, the 18-year-old daughter of a Cuban rebel leader purportedly arrested for sedition in August 1897 who was also, according to William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, “the most beautiful girl in the island.” Evangelina’s picture became a tabloid staple, her ordeal at the hands of her captors the topic of regular lurid updates. The melodrama ended only when Hearst’s paper announced, two months before the explosion of the USS Maine, that it had arranged for Evangelina’s escape to the United States. To celebrate her arrival as a “Cuban Joan of Arc,” Hearst organized a mass rally to which more than 75,000 New Yorkers arrived chanting “Viva Cuba Libre!”

In the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, the US agenda changed from justifying invasion to legitimating a continued military and economic presence. Accordingly, the representation of Cuba as a comely woman in distress–usually depicted, like Evangelina, as white in complexion (and thus a fair reflection of American virtue)–changed too. The mixed-race isle was now depicted in tabloid cartoons as a pitiable black child holding the hand of a beneficent Uncle Sam on the path to progress. Previously, US opponents of annexing Cuba had often based their arguments in racism. “The white inhabitants form too small a proportion of the whole number,” as one diplomat put it in 1825; moreover, explained a Congressman in 1855, “the Spanish-Creole race…are utterly ignorant of the machinery of free institutions.” Now the same logic justified a strong imperial hand. The Cubans, the commanding US general in the 1898 war declared, were “no more capable of self-government than the savages of Africa.”

If once Cuba had figured as a virtuous lady in need of saving by an imperial enterprise cloaked in a mission civilitrice, it soon came to be seen as a different sort of woman, one whose mission was servicing others. “We gave Cuba her liberty,” declared a US Army veteran on holiday in Havana in 1925, “and now we are going to enjoy it.” The island’s bustling main seaport had never been a stranger to prostitution. But as the tourist trade grew, so did Havana’s reputation as “the brothel of the New World.” The island “was like a woman in love,” touted a typical travel writer’s account, and “eager to give pleasure, she will be anything you want her to be.” Simultaneously overseas and right next door, Cuba became the place where Americans–especially American men–went to escape the stolid mores of wife and home. With the passage of Prohibition in 1919, legal booze fortified Cuba’s libertine lure. When It’s Cocktail Time in Cuba was the title of a popular US tourist guide, and Havana bartenders concocted new rum-based elixirs like the Cuba Libre and mojito to coax more cash from Northern visitors. A short cruise from Florida–or, after Pan-American Airways launched its first international passenger route with Miami-Havana flights in 1928, an even shorter plane ride–Cuba was, by the 1930s, receiving more US visitors than even Canada.

By the time the US mob launched their Havana plot in earnest in 1946, tourism was already well established as a key portion of Cuba’s economy. Mob designs for “the Monte Carlo of the Caribbean” evoked European playgrounds, with hotels named the Riviera, Deauville and Capri. But by the 1950s, “Havana” had acquired its own cachet for American consumers as both brand and idea. On television Desi Arnaz was the all-purpose Latin Lover, and advertisements hawked Havana perfume, Havana soft drinks, Havana lingerie. “Waving palms, a cool island breeze,” went the slogan for El Paso brand Cuban Black Bean Dip. “Visit a forbidden paradise of silky black beans, sweet red pepper and an undercurrent of rich gold rum, resulting in a Cuban sensation that may taste mild, but is definitely hot, hot, hot!”

The cold war ended Havana’s viability as marketing hook for consumers to the north. That it also made Cuba legally forbidden to American travelers, though, doubtless contributes to a still-thriving trade in Cuba-related books in the United States–volumes that (no matter their particular topic or politics) often find it impossible not to trade in shopworn clichés about pulsing rhythms and caramel skin and crashing waves on the Malecón. Even in a book like T.J. English’s authoritative and otherwise sharply written Havana Nocturne, everything from Batista’s facial features to the city’s jazz scene is described as “exotic.” Never mind that the cultures of Cuba and the United States have always been more deeply intertwined than partisans of either nation have sometimes cared to admit. The jazz bands that thrilled American tourists in 1950s Havana borrowed from the inventions of musicians in New York and Chicago; and no less a touchstone of Americana than rock ‘n’ roll, as the music historian Ned Sublette has convincingly shown, owed as much in its genesis to Cuban rhythms ringing out of Havana as it did to blues riffs busting out of Memphis or New Orleans. Indeed, for two centuries up until 1960, the cultures of New Orleans and Havana were joined and nurtured by the streams of migrants and goods flowing between them.

What the “exotic” label also tends to conceal about Cuba is that to its own people as well as outsiders, the island has long been as much an idea as a country. At least since José Martí, the great poet laureate of Cuban independence, began composing odes to the island’s “half-breed” soul in the late 1800s, there has existed in Cuba an obsession with reflecting upon and debating the national character. This tradition is perhaps most memorably manifested in the seminal anthropologist Fernando Ortiz’s argument, in Cuban Counterpoint (1940), that all of Cuban identity and culture–from the rumba to the mulata to the cigar–can be understood as outgrowths of an economy based in producing tobacco and sugar for export. The discussion has taken many forms, but perhaps the dominant current in Cuba’s politics and intellectual culture has always been the struggle over cubanía, or Cubanness. Fidel’s revolution, before it was Marxist-Leninist or Castroist or anything else, has always been framed and experienced in Cuba as a nationalist struggle. Accordingly, it was not solely on the grounds of Marxian virtue but also cubanía that Fidel battled cocaine and prostitution as “un-Cuban” in the 1960s (never mind the Havana Mob’s avoidance of the drug trade, or that sex-for-pay held a prominent place in Cuban society long before its exploitation by yanquis) and contended, during the 1970s, that Cuba’s military involvement in Angola and Mozambique was driven by Cuba’s core identity as an “Afro-Latin” nation.

Fidel’s custodianship of cubanía has deep roots in a much longer history of Cuban men of privilege (and usually light skin) defining the nation’s identity. Batista was a mulatto cane-cutter’s son; Fidel and his brother Raúl were the children of wealthy Spanish landowners–putative members, that is, of a class of Cubans who thought the déclassé rule of an uneducated army colonel a national shame. Not every member of Cuba’s elite who came to support Castro against Batista in the 1950s was driven by prejudice; Fidel has always been a strong antiracist, in his way. But the machista worlds of elite Cuban politics and culture have always been paternalistic, whether in José Martí’s wishful 1891 declaration that in Cuba “there are no races,” or the longstanding tradition–from Nicolás Guillén’s iconic 1930 poem “Mulata” to innumerable paintings of the copper-skinned Virgen de la Caridad–of holding up the sexy mulata as embodiment of cubanía, while affording to actual brown-skinned Cuban women little place in that nation beyond its brothels and kitchens.

After racial discrimination was officially banned in 1960 by his revolution, Fidel blithely declared that racism was defeated in Cuba. As in 1891, the actual situation was more complex. The masses of Afro-Cubans who’d lived in illiterate destitution since slavery–and seen 6,000 of their forebears massacred in a horrific 1912 race war–had the most to gain from socialist projects in housing, healthcare and education. That Cuba’s 4 million blacks still provide a key base of Communist Party support is a measure of how much their lives have improved under Fidel. But as Carlos Moore writes in a poignant new memoir, Pichón, Castro’s blind spots with regard to race have at times also been pernicious. Pichón takes its title from a Cuban slur for Jamaican and Haitian laborers who survived the Depression by scrounging for slaughterhouse scraps in the manner of ugly black buzzards, or pichónes. The book begins with Moore recounting a rural Cuban childhood of being tormented by the fists and epithets of white schoolmates. Then comes the story of his personal epic: leaving for New York City at 16 in the late 1950s and falling into the black radical demimonde of Maya Angelou and Malcolm X, then returning to Cuba as an ardent Fidel admirer in the early 1960s, only to be imprisoned and exiled by Fidel’s revolution for daring to protest the race prejudice of certain of its ministers.

Moore renders this tragic tale with frank clarity. He met his mentor Angelou in a Harlem bookshop shortly after his arrival to the cosmopolis in 1958; scarcely two years later, he directed an occupation of the UN General Assembly to protest the US-sponsored killing of the Congolese freedom fighter Patrice Lumumba. It was during Castro’s own 1960 visit to the UN–during which Fidel stayed at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem to convey solidarity with those oppressed by the US empire at home–that Moore decided it was his revolutionary duty to join the cause.

Returning to Havana in June 1961, Moore sought to put his skills as an English speaker to work at the Foreign Ministry. He became convinced that the bureaucrat denying his requests for a job was doing so on account of his dark skin, and he took the audacious step of traveling to a provincial army barracks to demand a meeting with the only Afro-Cuban member of Fidel’s inner circle, the guerrilla hero Juán Almeida. Almeida indulged the headstrong youth with a warning to “stop talking as you do,” but once back in Havana, Moore was “detailed” by the revolutionary police and tossed into a new jail made from a converted mansion on the city’s outskirts. He was released a few weeks later with no charge or explanation and eventually found work in another branch of the government. But in late 1962, after some months of increasing disquiet about the revolution’s puritanical excesses–with police sending homosexuals to labor camps and forcibly shuttering Afro-Cuban social clubs–Moore encountered his old nemesis in the Foreign Ministry. Furious that the young negrito was still at large, the bureaucrat promised to ensure that Moore was “take[n] care of” for good. That afternoon Moore knocked at the door of the Havana embassy of the new West African nation of Guinea and requested asylum; a few weeks later he left Cuba on a freighter bound for Africa. Eventually settling in Paris, he went on to write Castro, the Blacks, and Africa (1989), a controversial radical critique of the revolution’s race mores whose exaggerated animus, given the experiences related in Moore’s more personal and worthwhile memoir, is perhaps now clearer at its source.

When Moore went into exile in the early 1960s, most Cubans who fled the island belonged to its white upper classes. The arch-right-wingers among them nurtured a deep anger about Castro’s “giving it all away” to the riffraff and pichónes. Their story is perhaps less tragic than that of exile families with more liberal pasts like the Bacardis, owners of the eponymous liquor empire, whose story Tom Gjelten traces in his splendid family chronicle Bacardi and the Long Fight for Cuba. The tale begins with the penniless Catalan immigrant Facundo Bacardi’s discovering, in the 1860s, a new way to distill sugar cane into clear white rum. His son Emilio Bacardi became a key ally of José Martí in the fight for independence in the 1890s, and the Bacardis’ 1950s heirs were fervid Fidel supporters–but then left the island and became fervid Castro-haters when he ordered a state takeover of the company they’d spent a century building from scratch. (One of Fidel’s great claims to revolutionary virtue is that he did not spare his own parents’ latifundio from being nationalized and split up in the first agrarian reform.) Family sagas about seized storehouses and abandoned mansions compose the sacred text of mainstream Cuban-exile politics. But as stories like Carlos Moore’s show, belonging to a class of Cubans whose lot the revolution improved granted no exemption from being tyrannized by party discipline and hierarchy.

When Fidel Castro took command of Havana in January 1959, few in or outside Cuba knew much about him beyond his magnetism and rousing oratory; apart from Castro’s loathing of Batista and idolizing of Martí, his politics–as the Eisenhower administration’s “watch and wait” approach to his government shows–were vague even to close observers. Soon enough, his strident nationalism and messianic bent were clear. But even as Castro’s government began seizing lands owned by US companies as part of its first agrarian reform in June 1959–and powerful Washington interests began urging Eisenhower to respond by ending the longstanding US agreement to purchase most of Cuba’s sugar–few foresaw the antagonisms and escalation to come.

With Cuba’s continued access to the chief market for its main crop looking unsure, and radicals like Che Guevara at Fidel’s ear, whatever doubts Castro had about Leninism disappeared. In February 1960 a delegation of Soviet ministers arrived in Havana and signed an agreement to purchase much of Cuba’s sugar; Che traveled to Moscow a short while later to secure Havana’s ties to the Eastern Bloc. Three years after Khrushchev had promised “we will bury you,” the Soviets had established a Communist beachhead in easy range of Florida, on an island, moreover, that the United States had regarded as an amour propre. The trauma was deep. In Washington a flurry of panicked recriminations over how this could have been allowed to happen–traced by Lars Schoultz with insightful verve in That Infernal Little Cuban Republic, a comprehensive history of US-Cuba relations since World War II–was translated into an ill-conceived CIA-sponsored invasion in April 1961. The Bay of Pigs fiasco did Fidel the great favor of allowing him to oversee the defeat of imperialist invaders on Cuba’s beaches. In the months following, the Kennedy administration hatched a tragicomic series of attempts to kill Castro with explosive seashells and poisoned cigars (a job for which the CIA contracted the president’s old Havana pimp, Santo Trafficante, now in Miami). But no matter. In October 1962, Washington’s worst fears were realized when a US spy plane over Cuba’s countryside snapped photos of Soviet missile launchers nestled amid royal palms.

Whether or not the Cuban missile crisis was the most dangerous and direct confrontation of the cold war, it’s clear that Cuba’s role was that of pawn or prop. This did not comfort Castro, who harbored deep resentment when Khrushchev failed to consult him before Moscow agreed to remove its nuclear missiles–a reaction that reveals the particularly Cuban pathos of this puffed-up leader of a smallish island driven by the need to be treated and seen as head of a big powerful nation (or at least a sovereign one). The longstanding US irritation with Cuba, Schoultz observes, stems from its leaders’ persistent denial of the base precept of political realism distilled in Thucydides’ dictum that the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must. Schoultz presents his history as a “case study in the trials and tribulations of realism”–an investigation into how for the past fifty years a weak state has “gotten away” with standing up to its vastly stronger neighbor and how, conversely, the stronger was made to let the weaker do so.

For three decades, of course, a large part of how Cuba “stood up” to the US empire lay also in its becoming the client state of another empire. This truth did not prevent Cuba from becoming a new kind of symbol across a Latin America long frustrated by the condescension of its Northern hegemon. Across the hemisphere, the mythic story of Cuba–a miraculous fable about a merry band of longhairs who went into their country’s mountains and a few years later swept into its capital on the shoulders of its poor–was one that women and men who loved justice would seek to re-create from El Salvador to Colombia to Bolivia and Peru. In Washington, conversely, a new guiding metaphor for Cuba emerged: that of a malignant cancer whose spread had to be contained at all costs. And so it was that many thousands of those Latin Americans who went to the continent’s jungles during the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, some toting photos of Che and Fidel in their knapsacks, died awful deaths with those whose cause they raised, too often the “disappeared” victims of US-backed dictatorships and death squads.

Since the cold war’s end, US policy mavens have argued over the extent to which those dark decades’ abuses were, if not justifiable, understandable given the strategic threat posed by the prospect of another Soviet satellite in its “backyard.” What the years since the USSR’s fall have also laid bare, however, is the extent to which Washington’s approach to Cuba itself has been driven by other than simply rational aims like containment. “Castro is not merely an adversary, but an enemy,” a 1993 report from the US Army War College observes, “an embodiment of evil who must be punished for his defiance of the United States…. There is a desire to hurt the enemy that is mirrored in the malevolence that Castro has exhibited towards us.” For US politicians in national campaigns, being “tough on Cuba” long ago took its place with being “a friend to Israel” as a sine qua non of victory. As Cuba’s potential threat to US security has progressively dwindled to nearly nil, US antagonism toward its government has only deepened. The Cuban Democracy Act of 1992 codified the embargo as US law and was toughened in the Helms-Burton Act signed by Bill Clinton in 1996, which prohibited US companies from dealing with foreign firms engaged in business with Cuban property seized by the revolution, and also mandated that the embargo could not be lifted until such time as Cuba is run by a government “that does not include Fidel Castro or Raúl Castro.”

More recently, George W. Bush, who owed his presidency to south Florida, used his office in 2004 to funnel $59 million in new funding to no-bid Miami-Cuban boondoggles like the propaganda networks Radio and TV Martí. He also moved to close one of the embargo’s few loopholes by introducing strict limits on remittances Cuban-Americans may send to family members on the island and on the number of trips they may take to visit them. Bush also placed Cuba on the US list of “state sponsors of terror” (based on an alleged chemical weapons program whose existence his own State Department doubted) and, in the long run-up to the 2004 election, established, at the heart of the executive branch and under the chairmanship of Secretary of State Colin Powell, a Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba. It was charged with determining how “to hasten the end” of the Castro dictatorship and in May 2004 produced a report recommending, for example, that in the wake of an anticipated violent transition, Cuban schools be kept open “in order to keep children and teenagers off the streets.”

As Daniel Erikson shows in The Cuba Wars, a sharp and deeply reported account of dynamics informing US-Cuba policy since the Clinton administration, Castro’s government was concerned that Cuba’s involvement in Bush’s “war on terror” would go beyond the United States’ use of its imperial relic at Guantánamo Bay to hold certain prisoners beyond the jurisdiction of US courts. The Cubans “were really worried,” Lawrence Wilkerson, longtime chief of staff to Colin Powell, tells Erikson of a visit he made to Havana just after leaving the State Department in 2005. “They wanted me first of all to assure them that we weren’t going to invade.” In the spring of 2003, Fidel Castro–practiced in paranoia, always more comfortable on a war footing than not–responded to the new provocations by ordering the trial for treason of some seventy-five “dissidents,” some of whom were indeed Cubans being paid by the United States to tweak (if hardly, in practice, to destabilize) their government, but most of whose offenses amounted to writing articles and circulating petitions. Some fifty-odd of “the 75” remain jailed today.

In 2003 I was living in Havana, and as at so many other times when Cuba had become the subject of hyperventilated fits abroad, the arrests and diplomatic volleys were little more than background noise to the struggles of quotidian life. People who sought more food than allotted by their ration card broke the law daily. That spring, an architect I was friendly with began selling stolen shellfish to feed his family, and his cousin had taken to earning new clothes by satisfying the bedroom predilections of Italian sex tourists. More significant to Cubans than Washington’s longstanding obsession with upending their government were concerns over what that government might do to repair a broken economy. Such grave ills aside, not a few Cubans remain proud that theirs is a poor country in which “no children sleep in the streets,” as a propaganda billboard near my Havana apartment touted truly. The Communist Party enjoys significant support, especially in the provincias–where peasants fifty years ago lived in dirt-floored huts and still do so today, but now regard free healthcare for their parents and good schools for their kids as birthrights. More generally, it’s open to debate whether the Cuban state’s solicitude toward its young and its aged is “worth” the repression too often endured by everyone else. But from the standpoint of a failed fifty-year attempt by the United States to change the island’s government by isolation, the salient facts about Cuba are that it enjoys good relations and strong economic ties to every other country in the hemisphere, including Canada (not to mention China and the European Union), and that it has a stable government, in evidently firm control of its military and police, which has carried off its recent change to a new head of state with apparently minimal fuss.

Raúl Castro–longtime head of Cuba’s military, a dour party man–has, with the illness of his brother, been cast in the unlikely role of reformer. Many in Cuba express hope that Raúl’s early gestures at reform, like his opening of the grounds of tourist hotels such as the Hotel Nacional to ordinary Cubans, may augur a larger opening of the Cuban economy. During the presidential campaign, Barack Obama called Raúl’s bluff by suggesting that he’d be willing to sit down with Cuba’s new leader with a view toward improving relations. Realists predictably think this prospect, like Raúl’s proffering of Cuba’s “willingness to discuss on equal footing the prolonged dispute” with the United States, is a nonstarter: Obama’s secretary of state, back when she was not his head diplomat but primary rival, called his willingness to meet with “foreign dictators” like Cuba’s new leader “irresponsible.” But during its first weeks, the Obama administration–no doubt cognizant of polls showing that younger Cuban-Americans voice little support for the hardline stance of the past, and that even a symbolic thaw with Cuba would be an easy way to improve relations with the rest of Latin America–successfully marshaled a bill through Congress overturning Bush-era restrictions on family visits and remittances. All this move does is return the United States’ Cuba policy to its 2003 status. But it was a key signal that a larger overhaul of the Cuba policy will be on the table in Obama’s Washington. At April’s Summit of the Americas, the president observed that Cuba’s thousands of doctors dispersed throughout the region were “a reminder for us in the United States that if our only interaction with many of these countries is…military, then we may not be developing the connections that can, over time, increase our influence.” Obama also declared that a “new beginning with Cuba” could be near. That initial signal, it seems, has been confirmed.

In 1891, José Martí, the most articulate of Cuban nationalists and also perhaps his generation’s most perceptive writer on inter-American relations, wrote in Nuestra América, “One must not attribute, through a provincial antipathy, a fatal and inbred wickedness to the continent’s fair-skinned nation simply because it does not speak our language, or see the world as we see it, or resemble us in its political defects, so different from our own.” For many Cubans, the election of Obama represents an overcoming of political defects, and in his brown face they see not a “fair-skinned nation” but something of themselves; their hope is that Obama will be a leader free of many of his country’s old neuroses. The ultimate test of those hopes will be ending the long-running embargo, which Wilkerson, expressing a widely held but rarely stated Washington view, called, in an interview with GQ, “the dumbest policy on the face of the earth.” No less incontestable is a remark made in 1974 by the now-ailing barbudo in Havana, who recently expressed doubt that he’d live to see the end of Obama’s first term. “We cannot move, nor can the United States,” Fidel Castro observed in an interview. “Speaking realistically, someday some sort of ties will have to be established.”