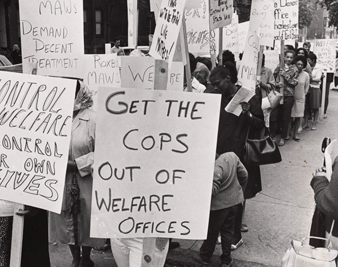

BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY, PRINT DEPT.Mothers for Adequate Welfare protest, Boston, 1966

BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY, PRINT DEPT.Mothers for Adequate Welfare protest, Boston, 1966

The year 1943 seemed, to contemporary observers, “1776 for the Negro”–a revolutionary time in which the promises of full citizenship for African-Americans were finally to be redeemed. Franklin Delano Roosevelt had desegregated the war industries two years before, and blacks were migrating en masse from the Jim Crow South to Northern cities, streaming into decent-paying jobs as welders, shipbuilders and machinists. The war was stirring a passionate commitment from black Americans, who came to understand it as a fight against fascism abroad and racism at home–and to understand themselves, in turn, as democracy’s cutting edge.

Yet in retrospect 1943 was also a time of quiet counterrevolution, in which longstanding inequities were being consolidated under the pretense of business as usual. The National Association of Real Estate Boards, for instance, issued a seemingly innocuous brochure titled “Fundamentals of Real Estate Practice,” which warned realtors that, no matter the size of the down payment on the table, they needed to guard against selling to undesirable elements. “The prospective buyer might be a bootlegger who would cause considerable annoyance to his neighbors, a madam who had a number of call girls on her string, a gangster who wants a screen for his activities by living in a better neighborhood” or–the grace note here–“a colored man of means who was giving his children a college education and thought they were entitled to live among whites.” Just as more blacks were earning enough to consider moving to better neighborhoods, that is, realtors were being instructed that they needed, in defense of American property values, to stave off this “form of blight” and nix any such deal.

It might seem incongruous to lump together bootleggers, madams, gangsters and upwardly mobile black Americans, as if black wealth were a form of ill-gotten gain, but that bitter absurdity sits at the heart of Sweet Land of Liberty, Thomas J. Sugrue’s panoramic account of the civil rights movement in the North. Again and again, Sugrue shows, Northern blacks rallied against racial inequality but were shut out from postwar prosperity–isolated from job- and tax-rich suburbs, their neighborhoods demolished or cordoned off by urban renewal, their schools left underfunded and decaying–in an exclusionary process ratified by state-backed policies and court-issued decisions. Sweet Land of Liberty is a sobering and meticulous excavation of the barriers to Northern black advancement in the three decades after World War II–an invaluable historical primer on why, even with the recent expansion of the black middle class, black household wealth remains distressingly low on average, only one-tenth of that of white households.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

The book is also a bold, if decidedly underdramatic, rewriting of civil rights history. In now-standard accounts like the PBS documentary Eyes on the Prize, the Northern movement literally explodes into view with the urban insurrections of the mid- to late ’60s–with Stokely Carmichael’s chant of “Black Power” taken up in burning cities from Watts to Newark. From this angle, the Northern civil rights movement seems to coincide with the starburst, and subsequent flameout, of Black Power, and Black Power appears largely as a betrayal of Martin Luther King Jr.’s inclusive vision rather than as a strategy that evolved from the painful dilemmas faced by the Northern side of the movement.

Sweet Land recovers an altogether different Northern movement, one that generally operated far from the cameras of the major networks (though black newspapers like the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier covered it fastidiously). Its most powerful foot soldiers were not men packing guns but mothers carrying picket signs and filing legal briefs on behalf of their children, community organizers armed with clipboards and pens, and social scientists wielding an array of statistics to press the cause. Sugrue offers a history of the Northern civil rights movement in which the Black Panthers have been demoted to bit players, Angela Davis and the Attica prison revolt make no appearance and a less-celebrated band of local activists–from smaller cities like Jersey City and New Rochelle–dominates the stage, battling against faceless if powerful entities like the National Association of Real Estate Boards.

It’s not an easy story to tell. The old civil rights story may be profoundly incomplete, as Sugrue and a new generation of historians have suggested, but it owes its endurance to undeniably riveting characters and an easily grasped dramatic arc, from the “once upon a time” of Brown v. Board of Education to the qualified “happily ever after” of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Even a historian’s historian like Sugrue sometimes struggles to animate his tale, which is mostly the arcless story of how local activists exposed hidden structures of inequality, only to learn they were much more difficult to dismantle than to describe. That said, having a movement that doesn’t move was a much more poignant problem for the movement itself, which was stymied in no small part because its adversary was changeable, elusive and frustratingly impersonal–often simply “the market.” Unlike in the South, few Northern whites openly defended racial injustice. The sorting of blacks into less desirable schools, careers and neighborhoods, they suggested, “just happened”–an argument that resonated in the culture and, perhaps more fatefully, in the courts, where justices interpreted Brown v. Board of Education as a mandate requiring proof of discriminatory intent. Iconoclastic NAACP lawyer Paul Zuber, one of Sweet Land‘s heroes, summed up the South-North contrast this way: “Down home, our bigots come in white sheets. Up here, they come in Brooks Brothers suits and ties.” The racism of the North wore the robes of cultural legitimacy; to many whites, it was wrapped up in their pursuit of the American Dream.

One of the most insistent lessons of Sweet Land of Liberty is that not all Northern segregation was created equal–and that the more segregation created channels of economic opportunity for white parents and their children, the more fiercely it was defended. Activists were generally able, through cunning and courage, to dismantle segregation where wealth seemed less at stake–for instance, in the realms of public accommodation and amusement. Take the case of the NAACP campaign against the RKO chain, which, like many Northern movie theater chains in the 1940s, found ways to turn away black patrons while publicly conforming to antidiscrimination statutes. Its ticket sellers would not overtly reject black customers: they simply would stop work when blacks arrived at their counter or find some other means of delaying the sale.

In response, the NAACP’s Cincinnati chapter fashioned a two-pronged campaign of litigation and civil disobedience. A black model citizen–James Smith, a “brilliant student and star athlete” at the University of Cincinnati–approached an RKO ticket counter, accompanied by three sympathetic whites. (The NAACP knew that only white testimony would be given sufficient credibility in the courts.) After he was refused service, Smith became a plaintiff in a lawsuit against RKO, repeatedly turning down RKO’s settlement offers in order to tie up the company’s lawyers.

Meanwhile, the NAACP organized dozens of “theater excursions” inspired by the Smith episode–more model black citizens queuing up, more white witnesses trained to observe discriminatory practice in all its particulars. Ticket sellers would sit silent rather than provide fodder for litigation, and the theater’s business often shut down for as long as a half-hour as employees scrambled to resolve the impasse. The campaign lasted nearly a year, but on May 24, 1941, RKO officially embraced nondiscrimination–a clear triumph for the NAACP, which, in Sugrue’s account, is credited with being more grassroots oriented and strategically imaginative than is commonly assumed.

By contrast, those activists who took on educational inequality and housing discrimination secured fewer straightforward victories. The Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, while directed toward Southern schools, had a galvanizing effect on Northern blacks, who seized upon its argument that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal”; the phrase offered hope that, whether or not a school district explicitly separated students by race, the courts would remedy instances of de facto segregation. Before Brown, Northern efforts to desegregate schools had tended to be located in smaller towns like New Jersey’s Toms River, Montclair and East Orange, where black communities were close-knit and segregation could be seen as a small-scale human failing. After Brown, the fight widened to larger cities and the structural patterns that lay behind educational inequity: segregation in education was tied, through the concept of the “neighborhood school,” to segregation in housing, and one could not be tackled without the other.

The 1960 campaign to desegregate New Rochelle schools suggests the inventiveness and tenacity of these post-Brown activists–and, again, of local chapters of the NAACP. The campaign’s flash point was the Lincoln School, which was attended overwhelmingly by black students and was so dilapidated that its building was sheathed in scaffolding to guard against falling bricks and concrete. The New Rochelle school district wanted to renovate the building; the NAACP, with the support of New Rochelle’s black parents, argued that the school should be closed down and its students transferred to other schools in the district. As the NAACP prepared its lawsuit in the fall, the black mothers of New Rochelle adopted a parallel strategy of direct action. They boycotted the Lincoln School, attempted to register their children at all of New Rochelle’s white-dominated elementary schools and staged sit-ins and marches on their campuses to draw media attention. New Rochelle was dubbed the “Little Rock of the North”; even Ghana’s prime minister Kwame Nkrumah blessed the effort.

The white parents of New Rochelle countered, in an argument that would gain traction over the coming decades, that they were colorblind liberals acting in the best interests of all New Rochelle children, black children included, by refusing to adopt a transfer policy based on race. “Nothing makes my blood boil more,” said New Rochelle’s school board president, “than a letter from the white citizens’ council saying ‘keep up the good work.'” The response was typical: by 1963, 75 percent of Northern whites said they supported the Brown decision–in effect, disassociating themselves from archsegregationists–but few supported desegregation measures in their own backyard.

In this superheated atmosphere, the NAACP filed its suit and won–Lincoln was demolished, black students were transferred–but on a larger level, the protests in New Rochelle and other Northern cities had a mixed effect. As a rule, the more integrated a school district became, the more white parents sought a way out–by moving to more “exclusive” neighborhoods or transferring their children to private schools–and, as a result, school districts often resegregated over time. Equity in education was a moving target. Paul Zuber, who had spearheaded the legal case in New Rochelle, persevered and ratcheted up his rhetoric. “Residents of expensive homes are not entitled to a public school attended only by children whose parents own expensive homes,” he argued in 1962. “The North has a choice. They can desegregate voluntarily, or they will be forced to do so.” Other activists, though, started to question whether it made sense to double down on the fight for integrated schools: perhaps it was better, given the rancor stirred by desegregation, simply to call for urban schools to be adequately funded and more accountable to the communities they served.

Open-housing advocates faced a similar dilemma by the mid-’60s. They had targeted restrictive covenants in the courts and sponsored several “move-ins,” in which middle-class black families were recruited to open up a wedge in all-white enclaves like Levittown, Pennsylvania. But white resistance was intense, and the rewards, while symbolically large, were logistically meager. It took several years to recruit a single black family, William and Daisy Myers and their three children, for the Levittown move-in, and then white Levittowners led an extended “war of nerves” against them, rallying outside their home during the day, breaking their windows at night and intimidating their supporters. The violence recalled segregation battles in the South, but the logic behind it had a Northern stamp: one white neighbor confessed to a reporter that William Myers was “probably a nice guy, but every time I look at him I see $2,000 drop off the value of my house.” Two years after moving into Levittown, the Myerses moved out, tired of the experiment. Like education activists, then, housing activists started turning away from the integrationist ideal and toward the thorny problems faced by poor and working-class blacks, who had been left behind in the search for “model” move-in families. The ghetto, not the suburbs, would become the new proving ground for housing reform, as tenant organizing and community-based economic development captured the imagination of the movement.

By the mid-’60s, even those desegregated RKO theaters seemed like a hollow prize, devalued by the same one-way flow of wealth to the suburbs that frustrated activists on other fronts. As whites fled cities for suburbia, the movie theaters followed–along with the swimming pools and amusement parks that had also just been integrated. Blacks ended up with fewer choices for diversion in the cities where they lived and were made to feel less than welcome in the suburban neighborhoods favored by entertainment chains; the consumer’s republic did not extend to them. Ever the structuralist, Sugrue concludes this relatively heartening chapter with a grim observation: “It was not coincidental that just as black consumers gained access to urban commerce, it began to decentralize.”

By this point in his story, Sugrue has offered a sharp corrective to prevailing civil rights narratives that place the movement’s center of gravity in the South before 1965. He has shifted our attention from the movement’s front-page victories to its “paradoxes and ambiguities.” In the process, by accounting for the deep-seated frustrations that surfaced dramatically in the urban riots of the mid-’60s, he has also altered our sense of the political battles of the late ’60s. It’s hard to see the white resistance to Black Power as a “backlash,” given that such resistance dogged the civil rights movement from its inception and was among the factors that sapped black activists’ faith in the project of integration.

What Sugrue does next, though, is more surprising still, and refreshingly independent-minded. While he pays tribute to Black Power’s ideological diversity and its search for alternatives to racial liberalism, he reassesses its usual exponents, the Black Panthers. He takes a dim view of the Panthers’ “romanticization of violence,” arguing that it became “a self-fulfilling prophecy” when authorities took literally the threats of police assassination illustrated, quite graphically, in the party newspaper. Sugrue also puts the Panthers’ community service programs in a rarely noted broader context: “Claims that there was something new and revolutionary about the establishment of free breakfast programs and health clinics revealed a willful ignorance of the extraordinary array of black-led and interracial social service agencies, meal programs, and health clinics, most of which operated off camera.”

Not coincidentally, “off camera” was precisely where women activists were likely to be at the height of Black Power, and Sugrue has kinder words for the alternative, and less theatrical, strand of black radicalism they sponsored. Generally speaking, the radicalism spearheaded by black men in the late ’60s was suspicious of the state. In the rhetoric of the Panthers, the state was a police state, and the “pigs” were the enemy; the language of revolutionary honor brooked little room for compromise. By contrast, female activists were more likely to exploit the opening provided by Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and to see the state as a provider of services, a welfare state. When Johnson’s war on poverty channeled funding to Community Action Agencies, women assumed positions of leadership: in Philadelphia, more than 70 percent of elected Community Action board members were women.

The welfare rights movement was, by Sugrue’s lights, the Northern civil rights movement at its finest–as rigorous as it needed to be to define a problem, and as supple as it needed to be to tackle it. Ideologically pioneering, it rebutted the prevalent notion that there was a “culture of poverty,” arguing instead that state policies around welfare created a poverty trap; moreover, it forced policy-makers, who previously had disparaged “matriarchal” families, to recognize the plight of poor women with children. Strategically resourceful, it asked poor mothers to march, social workers to change the system from within and activist lawyers to challenge the arbitrariness of eligibility standards in the courts. And through the creation of the umbrella National Welfare Rights Organization, it knitted together hundreds of local grassroots groups into a coalition that could press for changes on the largest structural level.

This broad-based interracial coalition was not only admirable; it was effective–a rare example of political success in a book full of campaigns that, however heroic, could not budge the systems they took on. The Supreme Court ruled that welfare was “not a gratuity” but an entitlement, and that welfare recipients had the right to a hearing before their relief payments were cut off. Politicians modified eligibility rules at the same time that poor women became more conscious of the benefits they were entitled to, and consequently there was a sea change in the administration of the system: in the space of ten years, the percentage of eligible families receiving benefits climbed from one-third to nearly 90 percent. Insofar as the war on poverty reduced black poverty, studies have concluded, it was due to this change in welfare disbursal.

Sweet Land of Liberty is so capacious, encyclopedic really, that it can be startling to realize all it leaves out–not in terms of ground it doesn’t cover but rather in terms of dimensions it doesn’t probe. Happily, it resurrects a cast of less-remembered activists and traces their individual itineraries; less happily, it does not ask why they devoted so much of their lives to the movement, how they sustained themselves in its darker moments or how their lives changed with its vicissitudes. The human drama we so often associate with civil rights history–A. Philip Randolph jousting with Franklin Roosevelt at the White House over the integration of war industries; Martin Luther King Jr. praying to God for guidance after the bombing of his Montgomery home–is passed over so that Sugrue might focus on the nuts and bolts of organization, policy and court rulings.

Sweet Land may even be, on principle, antipsychological: one of the book’s few openly polemical turns is Sugrue’s critique of how social psychology misled the movement, promising activists that if whites were in contact with respectable black men and women, they would be shed of their prejudice and equality would become the law of the land. As Sugrue underscores, whites in the postwar era did lose much of their animosity toward blacks–in a 2007 survey, 87 percent of whites claimed to have black friends–but that transformation of the white psyche has paid many fewer dividends than expected. It may have helped to elect a mixed-race African-American to the presidency, but black babies still die more than twice as often as white babies, black men still live six years less on average than white men, black Americans are still almost six times as likely to be incarcerated as white Americans and black communities are still ravaged by levels of violence unfamiliar to white America: in a recent study, 70 percent of blacks reported that they knew someone who had been shot within the past five years. We seem, that is, to have arrived at a near-reversal of the state of affairs that Swedish social scientist Gunnar Myrdal diagnosed in 1944: “The social paradox in the North is exactly this, that almost everybody is against discrimination in general but, at the same time, almost everybody practices discrimination in his own personal affairs.” The paradox nowadays is that fewer whites practice discrimination in their personal affairs, but at the same time, a powerful majority countenances discrimination in general.

Sugrue’s brief against the “prejudice” school of social psychology is convincing and should be required reading for all those pundits who enthused that Barack Obama’s victory meant that the civil rights movement could hang up a “mission accomplished” sign. (For those unrepentant holdouts, here’s another sobering statistic: among whites nationwide, John McCain beat Obama by a twelve-point margin.) Still, it’s one thing to document how a psychological paradigm created false expectations, and another to downplay the psychological dimensions of experience in toto. Sweet Land‘s activists analyze their dilemmas in a cultural and emotional vacuum; they can seem like walking position papers, people with no time for such frivolities as family, church or entertainment–this despite the fact that the rise of “soul” culture counts as one of the Northern civil rights movement’s most lasting contributions to American life. Fittingly, the book has an especially high regard for social scientists who gathered data, crunched numbers and produced reports documenting inequality–intellectuals who, in their faith in the power of statistics, much resemble Thomas J. Sugrue.

The problem here is not that Sweet Land‘s analysis is wrong but rather that the book isn’t equipped to meet the larger challenge it faces: how to animate those damning statistics, and the lives of those who have struggled against them, so that they have the strength to take on the morality-play version of civil rights history, shift our cultural memory and galvanize a new debate about racial inequality. Against the traditional, and quite Christian, tale of sin, suffering, death and redemption, Sugrue offers a numbers-driven story of perseverance without relief–the myth of Sisyphus rather than A Pilgrim’s Progress. How to produce a PBS miniseries based on that?

Sugrue comes closest to capturing the soul of the Northern movement with the twin tales of Herman Ferguson and Roxanne Jones. Ferguson was a New York City teacher and school administrator, “one of those mild-mannered, slow-burning but very dedicated kind of guys,” in the words of a colleague. In the spring of 1963 he led protests against a Jamaica, Queens, bank for its “Billy Banjo” mural, a plantation scene with a smiling, strumming, barefoot Negro at its center. That summer, he spearheaded a campaign demanding that black workers be employed in the construction of a 6,000-unit apartment complex. The demonstrations grew more militant until, in September, Ferguson and eight other protesters broke into the construction site, locked themselves to the top of a crane and threw away the keys. By the end of 1963 the campaign had widened to include boycotts against neighborhood stores and had drawn in Malcolm X, with his call for black communities to “buy black.”

Yet while Ferguson’s methods became steadily more confrontational, they didn’t produce the hoped-for results: even “Billy Banjo,” with his wide grin and straw hat, was a tough, unmoving antagonist. By early 1964, Ferguson had joined Malcolm’s Organization of Afro-American Unity, chairing its education program. When Malcolm was assassinated not long after, Ferguson blamed the government and turned broodingly apocalyptic, eventually calling for blacks to “obtain weapons and practice using them” in preparation for the imminent race war.

His paranoia, while profound, was not totally misplaced. In 1967, Ferguson and fifteen other members of the Revolutionary Action Movement were arrested on charges of conspiracy, accused of having planned raids on the homes of more moderate civil rights leaders. Yet who were the actual conspirators here? Ferguson and his comrades had stockpiled guns and ammunition under the auspices of the “Jamaica Rifle and Pistol Club,” but an undercover police officer revealed, during the ensuing trial, that he was the one who had purchased the maps of the relevant neighborhoods and copied out the directions to the homes. When the jury–all white and all male–found Ferguson guilty under an obscure New York law forbidding “anarchistic” conspiracies, Ferguson refused to serve time, jumping bail and moving to the socialist state of Guyana, where he lived for nineteen years under an assumed name.

If Ferguson’s trajectory suggests a sadly familiar spiral of radicalization and repression, the story of Roxanne Jones is a tale less told, perhaps because it asks us to reconcile how, in the wake of the civil rights movement, black Americans have been simultaneously empowered and marginalized. Born in South Carolina in 1928, and the first black woman elected to the Pennsylvania State Senate, Jones lived nearly half her adult life on welfare and cut her teeth as an organizer with the welfare rights movement. In 1976 she co-founded Philadelphia Citizens in Action, an organization that advocated for the city’s poor in a post-Great Society moment. While Ronald Reagan conjured up the image of a welfare queen driving a white Cadillac, Jones highlighted the image’s absurdity. She herself could not afford a car–only a quarter of the people in her neighborhood even had access to one–and much of her community work tried to figure out how to shuttle people without cars to jobs outside their neighborhood. Through the early ’80s, she remained undeterred by the conservative counterrevolution, fighting back by filing a lawsuit against Pennsylvania’s workfare program and leading a two-week occupation of the State Capitol rotunda.

Deciding that community organizing was not enough to remedy the plight of the urban poor, Jones made an Obama-like transition: in 1984, two years after occupying the Capitol rotunda as a protester, she returned to it as a state senator, building bridges between policy wonks and welfare recipients, corporate attorneys and ex-cons. Like many black officials elected to legislatures in the post-civil rights wave, however, she found it easier to be re-elected than to influence policy. Most of her proposals were torpedoed by a Republican majority. One of her last acts was to introduce legislation that would provide reimbursement for the bus fares of poor children attending school; it too was defeated. By 1983, Pennsylvania’s welfare benefits had dipped below pre-movement levels; by 1992, federal welfare payments were 43 percent lower than in 1970. In August 1996, two months after Jones’s death, Bill Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, reversing the gains secured by Jones and other activists by limiting welfare to a temporary program.

It’s easier to explain why Herman Ferguson ended up in Guyana, the vanishing point of his militant journey, than to explain why Jones ended up a coalition-builder with no forceful coalition behind her, a lonely defender of the poor. Sugrue deserves much credit for forcing attention on the hard questions that the Northern civil rights movement asked of American society. He deserves even more for forcing attention on the arduous questions that the movement’s disappointments reflect back on us.