Brown University Students Are on a Hunger Strike for Palestine

On Friday, students at Brown began the longest hunger strike for Palestine in the US, calling on the university to divest their endowment.

A pro-Palestine rally at Brown University in February 2024.

(Brown Divest Coalition)At 12:30 pm on Friday, February 2, a group of 19 students at Brown University began what has become the largest hunger strike for Palestine in the United States since the war in Gaza began. The strikers have promised to refuse food until the university administration agrees to bring a resolution to the Brown Corporation, the university’s chief governing body, to divest its endowment from companies that provide weapons and equipment to the Israeli government.

Student activists say the strike was their last resort after the university refused to consider divestment following protests in the fall. Those actions included two separate sit-ins undertaken by more than 60 students, all of whom were arrested for trespassing.

“Although I feel a little dizzy, I do know that I am privileged,” said a Palestinian student at a rally on Monday during his fourth day without food. “If a medical issue was to arise, I would be immediately rushed to the hospital, something my people in Gaza no longer have.”

But even the health of students has failed to move the university administration. Hours after the strike was announced on Friday, President Christina Paxson sent a letter to the protesters saying she would not place a divestment resolution on the agenda for the corporation’s meetings scheduled for Thursday and Friday, as the strikers demanded.

In a 2019 referendum, 69 percent of voting undergraduate students supported divestment from companies that “facilitate human rights violations in Palestine,” but Paxson declined to bring the issue to the Brown Corporation. She wrote in a 2021 letter that “Brown’s endowment should not be used as an instrument to take sides on contested geopolitical issues over which thoughtful and intelligent members of the Brown community vehemently disagree.”

In her speech at Monday’s rally, striker Ariela Rosenzweig rejected the claim that the administration is not taking a side. “There is no neutrality,” she said. “There is only complicity or justice.”

Since the beginning of the invasion of Gaza, student activists at Brown have been at the forefront of nationwide efforts to pressure university administrations to divest their endowments. In November, 20 Jewish students held a sit-in in the university administration building, refusing to leave until President Paxson agreed to divest.

All 20 students were arrested but later had their charges dropped after three Palestinian students, including Hisham Awartani, a junior at Brown, were shot in Vermont. Two days after the shooting, the Brown administration held a vigil during which President Paxson was shouted off the stage with calls to divest.

In December, dozens of other students at Brown held another sit-in, and the university has continued to pursue criminal charges for this second group of protesters, which will have their arraignments on February 12 and 14.

“We exhausted all other avenues,” said Nour Abaherah, a Palestinian student and one of the hunger strikers.

Officials with the United Nations have warned that hundreds of thousands of Gazans are currently experiencing famine conditions as a result of the Israeli bombardment and invasion. For Abaherah, the choice of a hunger strike was intentional. “It’s also an effort to turn everyone’s attention to the state-sanctioned famine that Israel is weaponizing in service of its genocidal campaign.”

It is not the first time Brown students have held a hunger strike. In 1986, four students announced that they were refusing food until Brown divested from apartheid South Africa. Brown disenrolled the students, who then ended their fast.

Over the course of the current hunger strike, activists have held programming in the campus center, bringing in experts to hold teach-ins about the Israeli-Palestine conflict and artists to perform Palestinian music while holding mourning and prayer rituals. According to Providence Journal reporter Amy Russo, the university hasn’t allowed outside reporters to enter campus buildings to report on the strike.

“There’s nothing unusual about limiting reporters’ access to campus buildings, where individuals may have an expectation of privacy and where normal academic and administrative activity is taking place,” wrote university spokesperson Brian Clark to The Nation. “We’ve been particularly cautious about situations where Brown students or community members end up in news photos or broadcast clips and end up facing doxxing challenges as a result, because we’ve seen this happen multiple times since Oct. 7.”

In Friday’s letter to the strikers, Paxson copied from her 2021 letter in which she initially refused to take up the divestment recommendation, writing that a 2020 report from the university’s Advisory Committee on Corporate Responsibility in Investment Policies (ACCRIP) “did not meet established standards for identifying specific entities for divestment or the articulation for how financial divestment from the entities would address social harm.”

Student activists dispute these arguments. The ACCRIP report—which was produced over eight months and totaled 16 pages—was the starting point for a longer divestment process that Paxson never allowed to continue, activists argue. In the report, ACCRIP acknowledged that it had not yet identified specific criteria to determine which companies to divest from, but that it was planning to do so in the upcoming semester.

According to Paxson’s 2021 letter, she met with ACCRIP in February 2020, a month after the report was released, and informed the committee of her initial concerns about their research. The committee revised the report to address these points and sent a fresh version to Paxson the following month. Finally, a year later—after ACCRIP had been dissolved and replaced with a new body with a broader scope, the Advisory Committee on University Resources Management (ACURM)—Paxson wrote that the edited report still did not meet standards. The Nation could not find the edited version of the report that addressed Paxson’s concerns—only the original January 2020 report is publicly available.

Clark did not respond to a question about why this updated report appears to be unavailable.

Activists also claim that the Brown administration is applying a double standard in saying the 2020 ACCRIP report did not adequately articulate how divestment would reduce social harm. The Brown Corporation voted to divest from tobacco companies in 2003 and from companies that supported Sudan’s genocide in Darfur in 2006, both times with the reasoning that divestment, even if having marginal financial impact, would serve in a broader societal effort to raise awareness.

The 2020 ACCRIP report argued that divesting from companies that support Israel could have similar impact: “Due to Brown’s significant social influence, divestment campaigns like those against Sudan and South Africa were also effective in socially stigmatizing the human rights violations carried out in those countries. Additionally, when an institution like Brown stands up against blatant human rights violations, it sends a signal to peer institutions to do the same.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Despite this background and completed research, the Brown administration has repeatedly encouraged activists to submit a new request to ACURM to examine the issue of Israel divestment, which would, in effect, restart the months-long process that resulted in ACCRIP’s 2020 report.

“We know that that is essentially a distraction tactic. The administration wants to stall us,” said Rosenzweig. “We’ve been through all of the appropriate processes already. There’s no reason to do them again.”

“There is an active genocide, so to put us through these extra means, these extra channels, when this is a very time dependent issue…. this isn’t something that can wait a week. It honestly shouldn’t be waiting another day,” Abaherah said.

The strikers presented to the administration what they called “A Critical Edition” of the 2020 ACCRIP report, intended to directly address the shortcomings that Paxson identified in the original findings. The now-50-page report adds allegations of social harm on the part of the Israeli government and identifies specific criteria to determine which companies to divest from.

But there is little indication that the administration is prepared to change its mind ahead of this weeks’ corporation meetings and adopt the activists’ plan.

Professor of English Kate Schapira, who cowrote an op-ed in the Brown Daily Herald in support of the strikers, said she didn’t understand why the university was continuing to reject demands for divestment. “Why is this the approach that they’re taking? Why are they choosing, for example, the escalation of arrests or charges. If they’re experiencing this as some kind of threat, what is it that they understand as being threatened?”

Omer Bartov, a professor of Holocaust and Genocide Studies, said he doesn’t believe Brown or any university will ever take the action of divesting its endowment from companies that support Israel. He speculated that doing so would cause pro-Israel donors to stop giving financial gifts to Brown, adding that he personally has received significant pushback from some alumni for publicly expressing views critical of Israel. Institutions like Harvard have already begun losing donors, who believe administrators should take a stronger stance in support of Israel and against pro-Palestine activism on campus. “Presidents are there to raise money, and so the same goes for Brown. These are private institutions. They depend on money coming in from donors,” Bartov said.

If a hunger strike fails to push the university to change its mind, it is unclear what will. The strikers said they will end their fast after the corporation meeting, but they and other activists said they remain hopeful that Brown will eventually divest. “The rejection of our simple demands only intensifies our resolve,” Abaherah said.

On Tuesday, the fifth day of the hunger strike, Niyanta Nepal said she was feeling dizziness, fatigue, and muscle cramping, but that she has been journaling to remind her about the lives of Gazans she is fighting for. “I can’t imagine that there will not be a huge turning point in the US in general, the world in general, specifically in this university,” said Nepal. “So I think maybe right now it seems like a very far-off reality for folks, but I trust humanity and people enough to identify what is going on.”

“We definitely don’t stop. We definitely don’t give up. Our demands are moot after the corporation meets on the 8th and 9th, but our movement keeps going,” Rosenzweig said. “I can only say that I know that someday Brown will divest and I hope that it’ll be soon.”

More from The Nation

The “Save Chinatown” Coalition Goes on the Defensive in Philadelphia The “Save Chinatown” Coalition Goes on the Defensive in Philadelphia

The construction of a new basketball arena for the 76ers threatens to fill the neighborhood with more traffic and raise rents, according to activists with the citywide campaign.

Human Rights for Everyone Human Rights for Everyone

December 10 is Human Rights Day, commemorating the anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), one of the world's most groundbreaking global pledges.

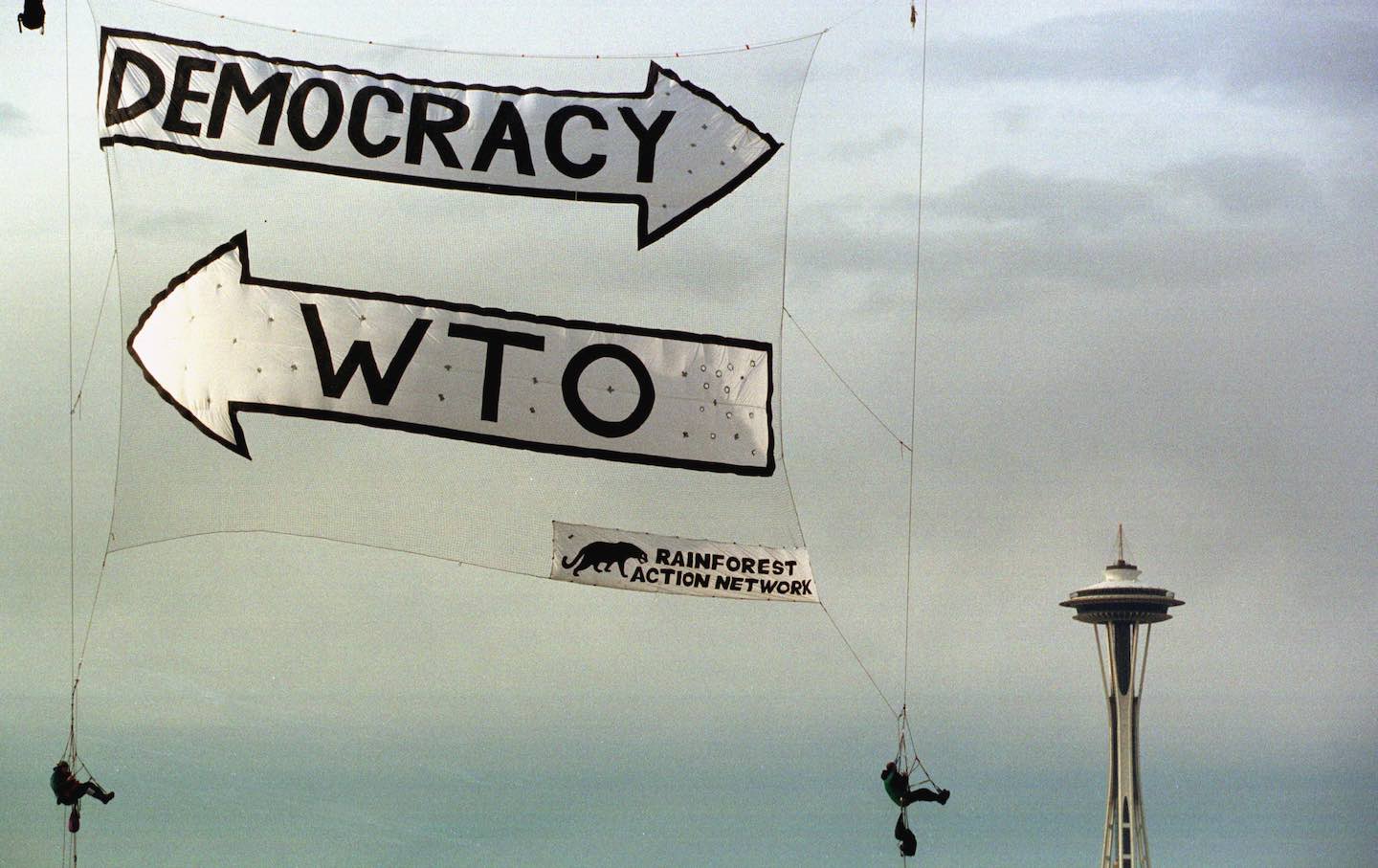

25 Years Ago, the Battle of Seattle Showed Us What Democracy Looks Like 25 Years Ago, the Battle of Seattle Showed Us What Democracy Looks Like

The protests against the WTO Conference in 1999 were short-lived. But their legacy has reverberated through American political life ever since.

Hollywood’s Vocal Actors Union Goes Silent on a Gaza Ceasefire Hollywood’s Vocal Actors Union Goes Silent on a Gaza Ceasefire

Amin El Gamal, head of SAG-AFTRA's committee on Middle Eastern and North African members, has advocated for a statement supporting a ceasefire in Gaza—so far without success

The Mirabal Sisters The Mirabal Sisters

Patria, Minerva, and María Teresa Mirabal were sisters from the Dominican Republic who opposed the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo; they were assassinated on November 25, 1960, und...

What Will a Peace Movement Look Like Under Trump’s Second Presidency? What Will a Peace Movement Look Like Under Trump’s Second Presidency?

An all-hands-on-deck approach to the coming world of Donald Trump and crew is distinctly in order.