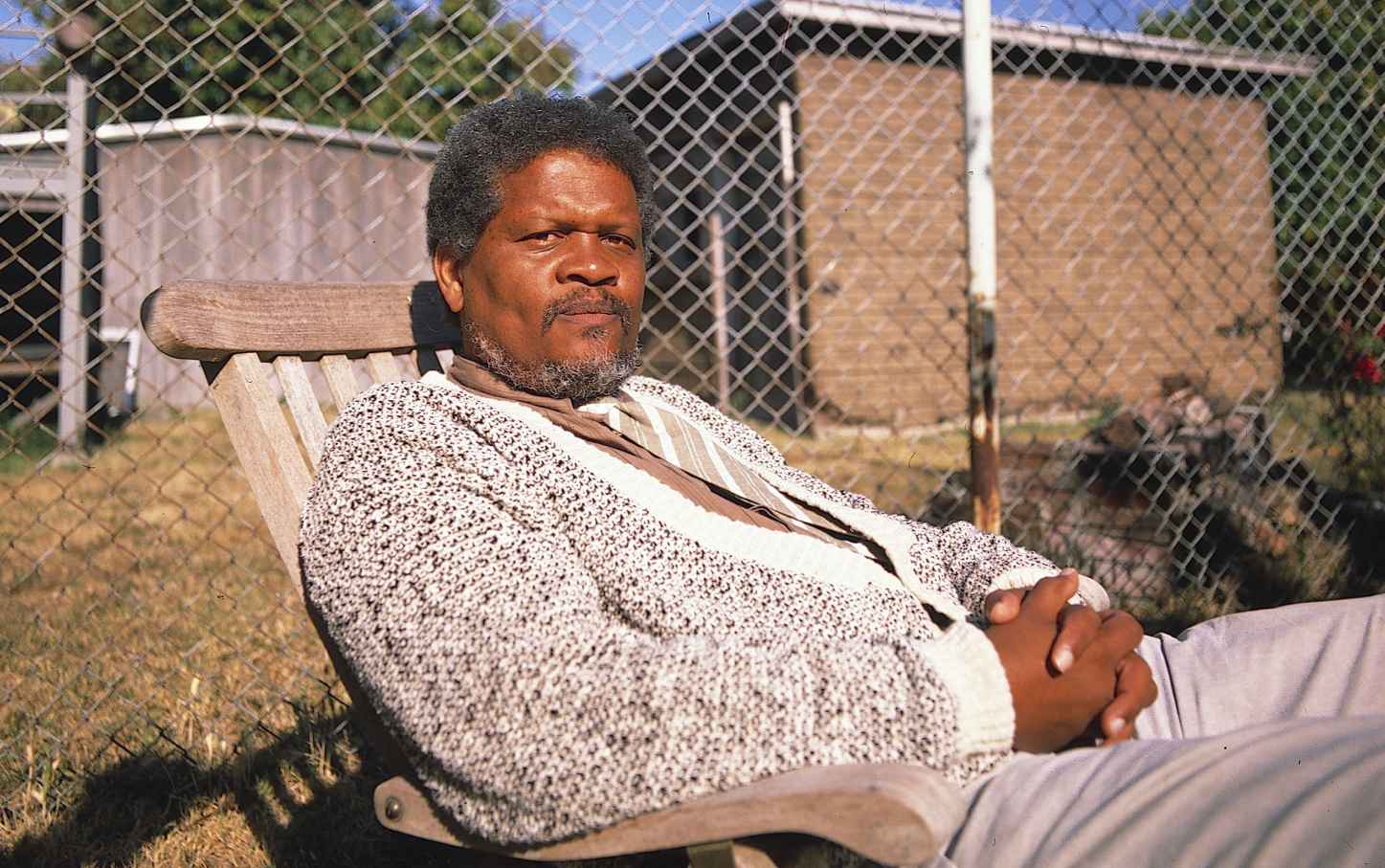

Ishmael Reed on His Diverse Inspirations

The origins of the Before Columbus Foundation.

In New York during the 1960s, I came under the influence of Black cultural nationalists, such as Askia Touré, the founder of the Black Arts Movement. The Umbra Workshop, which published four issues of a literary magazine with the same name, introduced me to Black history and culture, something that was absent from my education.

My world was Black and white, as I straddled between the white counterculture and Black cultural nationalism. In the Woodstock program, I was one of three writers cited as the counterculture’s favorites, but my work also appeared in Black publications, such as The Liberator and Cricket. Walter Bowart and I cofounded The East Village Other, the voice of the counterculture, but I also participated in fundraisers for the Black Arts Repertory Theater in Harlem.

The Beats influenced us. They brought American poetry from the parlor rooms of the elites to the streets. We were not aware of the proletariat writers of the 1930s who preceded and influenced them. They’d all but disappeared, but John Reed and Louis Ginsberg certainly influenced the Beats. However, the Beats were a predominantly white male movement, a fact that Anne Waldman effectively pointed out in Women of the Beat Generation, an anthology edited by Brenda Knight. My straddling of Black and white ended when I met Carla Blank, who, at the time, was one of the dynamic postmodern dancers and choreographers of the Judson Church movement.

Carla had connections to the Indian and Japanese avant-garde. Her collaborations with Japanese dancer Suzushi Hanayagi would lead to one of the first artistic responses to the war in Vietnam, called The Wall Street Journal. Both Suzushi and Carla became collaborators of the late Robert Wilson. Soon, Carla and I were members of a circle that included Chinese, Japanese, European, and Iranian artists. Among the circle members was the late futurist F.M. Esfandiary.

My grandmother told me that her father, Marion Coleman, an Irish American, had to flee Chattanooga after attempting to organize the pipe workers. He left behind his Black wife, Mary Coleman, who supported her children by setting up a food stand in her front yard, which served white and Black workers. She insisted that they address her as “Mrs. Coleman.”

My mother, Thelma V. Reed, single-handedly organized two strikes that led to the advancement of Black women workers. She writes about these victories in her memoir, Black Girl From Tannery Flats. I must have inherited an organizing gene from my ancestors. I organized teen clubs at the YMCA and a Buffalo theater group that featured the late poet Lucille Clifton. In New York, I assembled a group that included Carla, the feminist lawyer Flo Kennedy, folk singer Len Chandler, and Leah Bernstein, a writer. I called it International Mind Mining. This group was the predecessor to the Before Columbus Foundation.

The first sign of my implementation of a new multicultural awareness was the anthology 19 Necromancers From Now. Doubleday published 19 Necromancers From Now in 1970. I added a Hispanic writer, Victor Hernández Cruz, and Frank Chin, who is Chinese American. Victor was a teenager when I met him. He’d published one chapbook, Papo’s Got His Gun. We’ve maintained a relationship with Victor since 1966. He now lives in Morocco, and Carla and I published his most recent book of poetry, Guayacán. I’d read an excerpt from Frank Chin’s unpublished novel, A Chinese Lady Dies, in a newspaper called The Great Speckled Bird.

Necromancers became more than its original purpose, which was to highlight Black writing. Because Frank was included, Asian American writers met at the book party for the anthology. Following that party, Frank Chin, Lawson Inada, Jeffrey Chan, and Shawn Wong began a collaboration. They became known as “The Four Horsemen of Asian American Literature.” They published a manifesto for the Asian American Renaissance, which I suggested that the late Charles Harris publish. At that time, Harris was the publisher of Howard University Press. The anthology Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian American Writers, edited by Frank Chin, Jeffery Paul Chan, Lawson Fusao Inada, and Shawn Wong, has gone into a third printing and is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year.

After that party for 19 Necromancers, a god of Variegation seemed to steer us in the direction of the founding of the Before Columbus Foundation, a multicultural literary organization. At that time, however, multiculturalism meant “third world.”

About the same time, in 1972, the late Al Young and I began a magazine called Yardbird Reader. We published writers who were unknown at the time and who are now part of the canon, as are many of the writers who have received American Book Awards. Yardbird 3 was an Asian American issue.

In 1974, a historic conference took place in Ellensburg, Washington, where Al Young and I met Native American writers Leslie Marmon Silko and Phil George, and sculptor Neil Tall-Eagle Parsons. Lawson Inada, who attended the Necromancers party, was also present.

The Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines funneled seed money for the distribution of Black, Latino, Asian American, and Native American magazines through the Ford Foundation. Through CCLM, I received a grant totaling $5,000 to start the organization, which I called the Before Columbus Foundation.

Ethnic Gatecrashers

To be eligible to receive the $5,000 grant, I was required to name a partner. I chose Victor Hernández Cruz. From our office on Sixth Street in Berkeley, we began distributing magazines like Maize, Puerto del Sol, Tin Tan, and other publications.

A turning point for the organization came when the late Robert Callahan accused us of discriminating against white ethnics. Callahan’s letter changed the direction of the organization. We hadn’t thought of whites as ethnics. Callahan, like me, was an ethnic gatecrasher with ties to Hispanic and Native American communities. It was through Callahan that I met Andrew Hope III, the late Tlingit poet, who became the president of Before Columbus.

This meeting led to several trips to Alaska. Carla and I published a book of poetry by his spouse, the late Sister Goodwin, an Inupiat, whose book, There Is a Lagoon in My Backyard, was the first book of poetry published by an Inupiat woman. Carla and I were named honorary members of the Tlingit tribe at a 1998 Sitka potlatch.

Callahan introduced us to Italian American writer Lawrence Di Stasi and Jewish American poet David Meltzer, who, along with Alta, a poet and publisher of Shameless Hussy Press, joined the Foundation’s board. At my invitation, the late author Joyce Carol Thomas signed on. Rudolfo Anaya and Simon Ortiz were also among the early members.

In 1980, at my suggestion, we initiated the American Book Awards, drawing on my experience with the National Book Awards, which, given my expanded view of American literature, fell short in terms of diversity. The National Book Foundation has changed since then and become more inclusive. In 1980, we held our first awards ceremony at the West Side Community Center.

In 1981, The New York Times covered our second American Book Awards ceremony, held at the Public Theater at the invitation of the late Joseph Papp. Among the presenters were Toni Morrison, who would receive the award in 1988, and Donald Barthelme. Since then, we have held awards ceremonies in numerous cities, including Chicago, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Seattle, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Washington, DC.

Among the distinguished writers who have attended our awards at their own expense are the late John A. Williams, the late Gloria Naylor, Don DeLillo, and Edwidge Danticat, who brought her family. The 2025 awards drew A.B. Spellman, the best poet to emerge from the downtown art scene of the 1960s, and Errol MacDonald, vice president and executive editor at Alfred A. Knopf.

Among our directors are a recipient of the Presidential Medal for Literature, three former US poet laureates, two Pulitzer Prize winners, two MacArthur fellows, a chancellor of the American Academy of Poets, and a recipient of the Booker Prize.

Humble Beginnings

The Before Columbus Foundation operated out of a two-story building on Sixth Street in Berkeley, where we distributed magazines. Visitors who occasionally occupied the upstairs apartment included novelist Chester Himes; playwright Adrienne Kennedy, whose play The Ohio State Murders reached Broadway in 2021; and surrealist poet Ted Joans, the subject of the recent biography Black Surrealist: The Legend of Ted Joans.

In November 1987, I was named writer-in-residence for The San Francisco Examiner by William Hearst III. This residency came with the use of an apartment in Pacific Heights. I had returned from Harvard and found my inner-city neighborhood occupied by a crack operation. Before long, two gangs engaged in shootouts with each other.

I wrote a series of articles for the San Francisco Examiner about the invasion of Black Oakland neighborhoods by crack dealers, which occurred around the time of an exposé about the Reagan administration turning a blind eye to contra allies who were cashing in on California crack operations. Senator John Kerry proposed that three government agencies were aware of the situation: the Department of Justice, the Department of State, and the CIA.

Peace came to our neighborhood when an ex-felon rid the area of an Asian American gang. He sold his home for $160,000. An investor flipped it with a group of non-English-speaking workers, and it was resold for $800,000, raising the block’s property value. Since redlining confines Blacks to the status of renters, an exodus of our Black neighbors began.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The Examiner articles drew the attention of the developer of Oakland’s City Center, which was under construction. He invited us to move our operation into Oakland’s Preservation Park, where 16 historic Victorian-era buildings were moved and restored to avoid demolition. Preservation Park is one of the most beautiful urban sites in California.

On November 18, 1991, my article about the Before Columbus Foundation appeared in Time magazine, accompanied by color photographs of Preservation Park. We had arrived. We had graduated from 1446, where the furniture mainly consisted of chairs discarded from a demolished movie house. We had been poor and struggling. At one point, the situation became so dire that I asked Gundars Strads, our executive director for life, how we were going to make it. He replied, “through blind persistence.” It was his coworker Mary Burgess who created the administrative structure for the Before Columbus Foundation.

The Before Columbus Foundation operated on the premise that storytelling traditions existed thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans, countering the myth that storytelling began with the Puritan settlement. Puritans were not even the first Europeans to arrive in North America; the French followed the Spanish.

Justin Desmangles, a writer and former cultural broadcaster, became our chair in 2009. He has a monk-like devotion to the organization. Even while fighting a debilitating illness, he travels by Amtrak from Sacramento to Oakland to manage our affairs. He organizes not only the American Book Awards but also forums and speakers we sponsor at the Koret Library in San Francisco.

A Canadian Publisher

Significantly, Blind Persistence: The History of the Before Columbus Foundation has a Canadian publisher, Robin Philpot. Canada is where Benjamin Drew published The Refugee: or the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada (1856), a book that would never have been published in the United States, where “polarization” is marketable.

Our organization demonstrates that writers from diverse backgrounds are capable of collaboration—for 50 years. Our president is the Pakistani American writer and playwright Wajahat Ali. While our organization embraces Woke, so does our Black Pope, Leo. President Trump’s Antebellum Restoration wages a campaign against Woke without defining the term. It is the 21st-century version of the Lost Cause, because the United States has never been a white nation and never will be one.

More from The Nation

How Was Sociology Invented? How Was Sociology Invented?

A conversation with Kwame Anthony Appiah about the religious origins of social theory and his recent book Captive Gods.

How Immigration Transformed Europe’s Most Conservative Capital How Immigration Transformed Europe’s Most Conservative Capital

Madrid has changed greatly since 1975, at once opening itself to immigrants from Latin America while also doubling down on conservative politics.

A Living Archive of Peter Hujar A Living Archive of Peter Hujar

The director Ira Sachs’s transforms an intimate interview with the photographer into a film about friendship, routine, and why we make art at all.

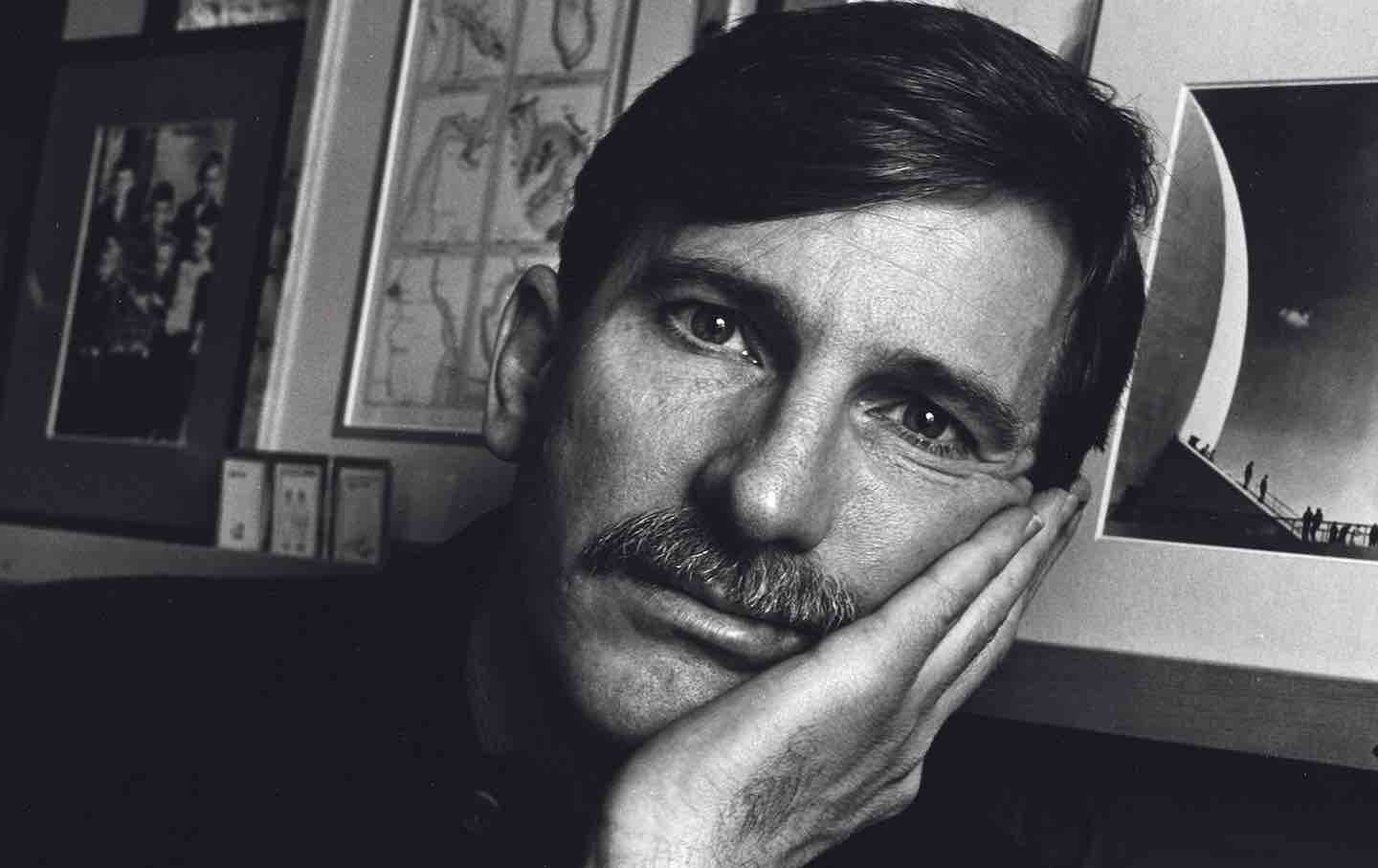

George Whitmore’s Unsparing Queer Fiction George Whitmore’s Unsparing Queer Fiction

Long out of print, his novel Nebraska is an enigmatic record of queer survival in midcentury America.

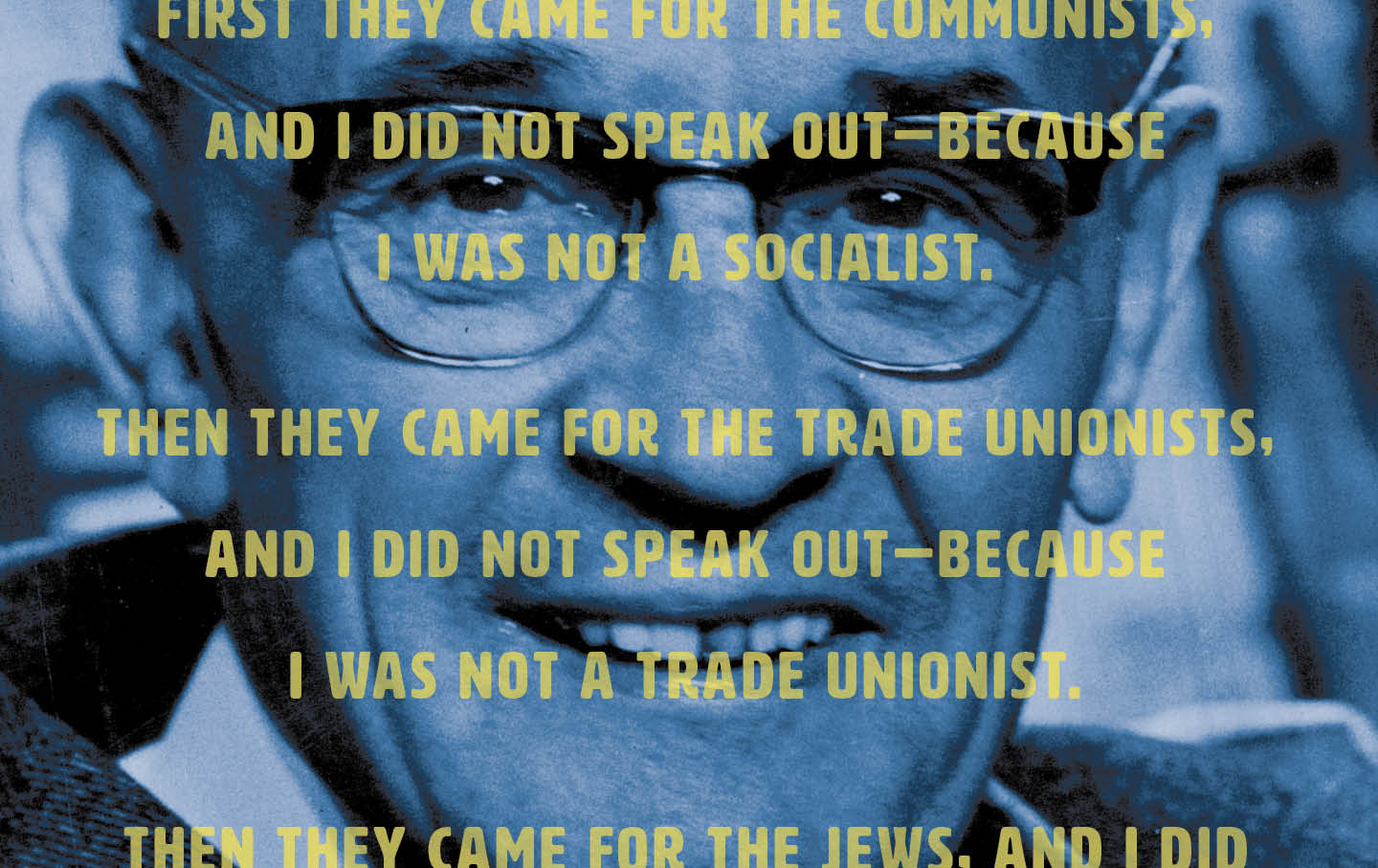

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”