A Firm Sense of Resolve

Helen DeWitt and Ilya Gridneff’s sweeping and experimental anti-war novel

Helen DeWitt and Ilya Gridneff’s Sweeping Anti-War Novel

Your Name Here dramatizes the tensions and possibilities of political art.

John D. Negroponte, a career diplomat and national security official, is something of a Forrest Gump figure in the sordid annals of postwar American foreign policy. Having entered the Foreign Service in 1960, he joined the US delegation at the Paris Peace Talks in 1968 as an assistant to Henry Kissinger—where he apparently clashed with his boss over the latter’s insufficient commitment to continuing the Vietnam War. As ambassador to Honduras from 1981 to 1985, Negroponte helped cover up the operation of notorious right-wing death squads and played a key role in facilitating US support for the Nicaraguan contras. Later, he threw his weight behind the North

Books in review

Your Name Here

Buy this bookAmerican Free Trade Agreement as George H.W. Bush’s ambassador to Mexico. And in 2005, he was appointed by Bush the younger as the United States’ first director of national intelligence, an office in which he inherited a sprawling infrastructure of CIA black sites and the practice of “enhanced interrogation techniques,” the latter of which he defended as “not that big a deal” as recently as 2012.

After such an illustrious career as a loyal servant of American empire, one might be surprised by Negroponte’s latest incarnation: He has popped up yet again, this time as a minor figure in Helen DeWitt and Ilya Gridneff’s collaborative novel Your Name Here. Originally released as a PDF on DeWitt’s website in 2008, and now available in print for the first time from Deep Vellum and Dalkey Archive Press, the novel is in its own way as ambitious as Negroponte’s march through the US State Department. Moving from New York to Berlin, London, and the Middle East, and exploring the nature of collaboration as well as the function of literature in an era of narrowed horizons, Your Name Here is an ouroboros: a meandering and digressive account of its own creation by two writers stymied by a parochial publishing industry and the exigencies of making rent.

It is rare for a novel to be cowritten —unlike, say, a work of nonfiction investigating the links between American diplomats and foreign paramilitaries of strategic importance to US interests—and so Your Name Here is already an experiment in enlarging our understanding of how fiction might be composed. But by making frequent, jarring reference to the military operations pulverizing Iraq and Afghanistan at the time of its writing, the novel also finds a canny way to capture how the drumbeat of war colonizes our imagination, no matter how far removed we may be from the front lines.

Over the past two decades, DeWitt has achieved something like cult status among a subset of serious readers. Best known for her indelible 2000 debut, The Last Samurai, she has published four other books since then, including the novel Lightning Rods in 2011, the story collection Some Trick in 2018, and the novella The English Understand Wool in 2022. Each has tackled a different if related set of concerns. The Last Samurai depicted the relationship between a brilliant but thwarted single mother, Sibylla, and Ludo, her preternaturally gifted son, who—inspired by the Akira Kurosawa film Seven Samurai—spends the latter half of the novel searching for a father figure worthy of the title when his biological one turns out to be a disappointment. Lightning Rods, meanwhile, plays with ideas about sexual harassment and salesmanship, while notions of fraudulence and connoisseurship animate The English Understand Wool, the story of an heiress who discovers that her wealthy parents are in fact kidnappers who embezzled her inheritance.

Acerbic, discursive, and studded with surprising formal choices, the novels frequently break from lyrical realist orthodoxy, even as DeWitt is telling recognizable stories about artists, workplaces, or families. Partly for this reason, many of these titles appeared long after they were completed. Take Lightning Rods, a satirical book about one entrepreneur’s scheme to dispel excess libidinal energy in the office by allowing men to copulate with undercover sex workers through high-tech glory holes. Though it was written mostly in 1998 and 1999, DeWitt had trouble getting it published after The Last Samurai because it was so different from her debut. After the rights reverted to her in the late aughts, 17 publishers passed on the manuscript before the storied independent press New Directions finally bought it in 2010.

There is no doubt that DeWitt’s fiction asks more from its readers than most mainstream novels do; that is its genius and a large part of its appeal. The publishing industry has been reluctant to support the kind of intellectually demanding, technically complex work that is her specialty: In addition to numerous foreign scripts, her fiction has incorporated mathematical equations, statistical graphics, and unorthodox typesetting techniques. In fact, the five books that DeWitt has published to date likely represent only a shard of her total oeuvre. In interviews, she has referred to them as “the handful of books by HDW which have escaped my hard drive.”

For its part, Your Name Here—written with Gridneff, an insouciant young freelancer who has since gone on to a robust career in investigative journalism and policy research—stuck around on DeWitt’s hard drive for nearly 20 years. It is to our benefit that Dalkey Archive has finally made it available as a physical object formatted to the authors’ specifications. The novel is shaped, explicitly and otherwise, by the dispiriting clashes with publishing gatekeepers that kept it out of view for so long. It also revisits several of DeWitt’s other enduring themes, including depression and the vagaries of genius in societies hostile to nonconformity. But more than any of her other works, Your Name Here asks how literature should respond to a reality that is equal parts vapid and violent, where the celebration of mediocrity is correlated with an utter disregard for human life.

This latter idea is expressed in Your Name Here largely through the omnipresence of the so-called War on Terror, a conflict that hums insistently in the background of DeWitt and Gridneff’s project. It is present from the very first chapter, when one of the novel’s many second-person narrators notices someone reading a copy of Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close on their flight. Only the text seems to have been tampered with to conjure an alternative publishing world in which the CIA funds literary projects covertly designed to increase the number of Arabists in the US population. Instead of corresponding with the physicist Stephen Hawking, as he did in the original novel, Safran Foer’s precocious child protagonist Oskar has written to Negroponte in this version, suggesting to him that “national intelligence would be improved if Arabic, Hebrew, Farsi, Pashtu and other so-called ‘exotic’ languages were to be introduced to a text of comparable popularity” as that enjoyed by The Lord of the Rings. As Oskar points out, Tolkien’s series has sold over 100 million copies, making it theoretically possible for legions of readers to master the dialects of various dwarves and elves while remaining ignorant of the myriad real languages spoken in the Middle East—a skill you’d think the US government might be interested in cultivating by any means necessary.

No single part of Your Name Here could be said to capture the novel’s entire bewildering scope, but the Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close episode does manage to signal many of its preoccupations: language, the cost of incuriosity, the degrading compromises that are sometimes necessary to fund challenging works of art, and—of course—the US invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq. Of the books that DeWitt has published since The Last Samurai, Your Name Here has the most in common, thematically and formally, with the one that made her name. Like that of Sibylla and Ludo, it is about the relationship between a hopeful neophyte and a mentor inured by experience, and like The Last Samurai’s profusion of quest narratives, it is also an assemblage of stories, albeit a more jagged and discontinuous one. Rather than nesting elegantly inside one another, its several distinct components, comprising texts both real and invented, accumulate in a more disorienting fashion. One narrator makes the comparison between the two novels unflatteringly explicit: “You’re reading Your Name Here, the new novel by Helen DeWitt. You’re extremely aggrieved. Instead of the wealth of stories you loved in the last book there are narrative strands which you find hard to follow.”

This kind of self-referentiality is one of a few ways the novel seems to anticipate trends in contemporary literary fiction that would emerge after it initially failed to find a publisher, notably the mainstreaming of autofiction, a genre that not only troubles the line between the real and the fictional but sometimes takes as its subject the composition of a work that may, in fact, be the one you’re reading. With its frenetic cross-cutting and inclusion of digital ephemera, you could also argue that Your Name Here prefigures what’s been called the “Internet novel” in recent years: fragmentary texts that replicate something of the experience of scrolling social media feeds while also largely being about scrolling social media feeds. The critic Jenny Turner, writing about the self-published version of Your Name Here for the London Review of Books back in 2008, observed that reading it was “like catching a flicker of the future.”

Nearly 20 years on, however, Your Name Here is less striking for its ability to channel the future than for illuminating the ways we’re stuck in the past, living in a world fundamentally shaped by the wars that are constantly intruding on DeWitt and Gridneff’s text. These interruptions come not only in the form of cameos like Negroponte’s but also as apparent non sequiturs, delivered by a voice that seems to issue from nowhere: “Patrick has also solved the first puzzle but did not understood the clue!!!!!!! Should he go to a magnet school? 80 people are dying a week in Iraq.” It’s difficult to read such lines today and not think about the vast numbers of Palestinians who, because of Israel’s genocidal siege, have died and are continuing to die in Gaza—a place that is mentioned at least four times in Your Name Here.

With US-backed bloodshed in the Middle East once again forming the substrate of our age, and so many of the other injustices suffered by DeWitt and Gridneff’s characters (austerity, inanity) now chronic phenomena, Your Name Here points to how fiction writers might engage with such realities beyond traditional representation. The novel’s sometimes maddening porousness has a way of bringing all kinds of repressed truths about contemporary existence to the surface, whether or not they have anything obviously to do with Your Name Here’s ultimate subject: itself.

If the late 2000s were marked by all sorts of difficulties for DeWitt in publishing her fiction, the early 2000s were not easy years for her either, despite how charmed her entrée into the literary world might have looked from the outside. The Last Samurai was undeniably successful—it sold 100,000 copies in English and was nominated for prestigious awards, including the Orange Prize for Fiction—but releasing it ushered DeWitt into a state of profound depression. Her contract had guaranteed her final approval on the text, yet she nonetheless found herself facing off with a recalcitrant copy editor, a time-and-energy-consuming burden that impeded her ability to make progress on other manuscripts. This was no mere inconvenience; as she put it on her blog in 2011, “There is a genuine risk of suicide if too much work is disrupted and destroyed.” The demands involved in promoting the book proved to be a similar drain. She described it this way: “So if you publish a book you have to go back and eat your own vomit. Then the physical object is available for sale, you’re expected to give interviews and go out and tell everyone how nice it tastes.” DeWitt wasn’t speaking only metaphorically: Her early experiences in the publishing industry literally made her sick, to the point of suicidal ideation and at least one failed attempt that was intrusively reported on by the New York media.

This dark period is, in some sense, where Your Name Here begins. When we meet “the reclusive Rachel Zozanian,” DeWitt’s fictional mirror, she has been alienated to the point of aphasia by the release of her novel Lotteryland, a satire about a society in which everything—not just goods but also qualities like “FIRM SENSE OF RESOLVE”—is distributed via lottery. Hospitalized after a breakdown, Rachel struggles to communicate with the well-wishers who call her incessantly on the phone; she picks up, and “sounds pour into her ear in the shape of words.” The only sentences she can bear to absorb are the exuberantly chaotic ones in an old e-mail written by a young stranger whom she once met briefly in a bar. The message—detailing, in roundabout fashion, romantic misadventures and a three-day bender—is from “Alyosha Popovitch Pechorin,” one of multiple joking pseudonyms for the novel’s Gridneff character that are derived from Russian literature and politics. (Alyosha Popovitch is a folkloric trickster; Pechorin is the protagonist of Mikhail Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time, the archetypal superfluous man.) Rereading the e-mail makes death seem less appealing to her.

When Rachel has recovered enough to relocate to Berlin and resume work on her next novel, she has two creative epiphanies: “What if the book becomes Kaufmanesque in its self-absorption (and so destined to be a cult classic)” and “What if I bring in a voice, that crazy anarchic voice, the voice that calls back zombies from the undead, the voice that dispels the anomie of the alienated third person orphan in schwarzweiss Kansas and hurls us Over the Rainbow into the glorious Technicolor of the first-person singular?”

That voice, of course, is Alyosha’s, and soon their collaboration is born. At first, Rachel tries to solicit commitments to publish Alyosha’s work from her industry contacts based on the strength of his wild e-mails, as if by doing so she might spare him the kind of spiritual damage she’s endured trying to make a living as a working writer. When this fails to pan out, Rachel offers him a flat £1,000 fee to use the e-mails in her own book; an adventurous reporter who funds trips to the Middle East by hunting down celebrity gossip for British rags, he always needs cash. But as the novel progresses, Alyosha (and Gridneff’s other avatars, like “Alexander Chatsky”) becomes a less passive muse and exerts more and more influence over the shape of the project.

This meta plot, much of which unfolds through e-mail exchanges between DeWitt, Gridneff, and their fictional counterparts, is parceled out piecemeal, alternating with the novel’s more obviously made-up strands as well as some ready-made ones. In addition to the aforementioned second-person sections, which attribute to the reader an array of disgruntled reactions to Your Name Here, there are also excerpts from Lotteryland (a real manuscript that DeWitt wrote 65,000 words of before it became part of Your Name Here); flashbacks to Rachel’s stint as an accidental sex worker at Oxford University; tabloid journalism by Alyosha; puzzles in Arabic that readers are invited to complete; and on and on. The War on Terror may seem at first an unlikely motif for such an extravagantly metafictional book, but it is in fact central to the conditions that Your Name Here implicitly—and sometimes explicitly—attacks.

Much of DeWitt’s fiction has protested against the learned helplessness that stymies contemporary intellectual life: the widespread tendency of people to recoil from difficulty or to accept defeat by unfamiliar concepts in advance, be they linguistic, mathematical, or scientific. Her books often contain pedagogical exercises designed to counter this inertia; as Sibylla teaches Ludo to read the Greek alphabet in The Last Samurai, DeWitt also teaches us. At the same time, she is attentive to the material obstacles that prevent people from engaging with, let alone producing, great works of art. Sibylla spends most of her days transcribing old British trade magazines like Horn & Hound for £5.50 an hour to keep herself and Ludo fed; she thinks wistfully of superb works of scholarship that she can’t afford to buy, and which she would not have the time to read carefully even if she could. In Your Name Here, a college-age Rachel discovers that “after a while you find the people you know are shadows of their possible selves,” blocked from the life of the mind by seemingly immovable forces. “What happens if you fight against being a shadow?” she wonders.

What happens, Your Name Here seems to suggest, is that you may wind up prostituting yourself, whether literally or metaphorically. Rachel’s youthful dalliances with johns are paralleled by her relationship with “wheeler-dealers” in the publishing and film industries, who sign her to supposedly “friendly” deals that strand her work in limbo in exchange for straightforwardly exploitative fees. Alyosha’s work as a gonzo paparazzo is framed as a similarly dirty compromise, even if he claims he’s only “making up stories that hurt no one and perpetuate the complexities of our post-modern melange.” The idea that you could make a living through art alone is a recurring punch line in the book: “And there’s always the novel, ha ha ha ha ha, there’s always the novel, ha ha.”

But in comparison with some of DeWitt’s other works, her and Gridneff’s Your Name Here makes clear that a culture that encourages ignorance and mendacity has consequences that go far beyond the aesthetic realm. It is a culture that apportions value as irrationally as the one in Lotteryland. A culture so used to dishonesty that it is primed to accept egregious lies by heads of state. A culture that would rather send young people to war than pay to educate them. A culture that rewards the architects of “national security” for knowing nothing about the languages or history of the regions they carpet-bomb. A culture that encourages serenity in the face of far-flung mass death but exhorts consumers to “Be brave!” in their choice of lipstick. As Turner writes in the London Review of Books, “DeWitt’s pedagogical daydreams lead to questions of fundamental human rights.” The blending of these registers suggests that a less insipid world might also be a more just one.

This is not to suggest that the novel’s repeated references to the War on Terror add up to something programmatic. On the contrary, this material can be outraged but also opaque, blithe, idiosyncratic, or uncomfortably tongue-in-cheek, much like Your Name Here as a whole. The book is refreshing not for being a particularly effective anti-war novel, but for dramatizing the feedback loop between a work of art and the political forces that shape its composition—even if the results only partially succeed.

One of the most perplexing passages in Your Name Here concerns a young Israeli woman of Iraqi Jewish descent named Noga Barakh Ohayon. She is one of the novel’s many disappointed “you”s: “You’re reading Your Name Here, the new novel by Helen DeWitt. You don’t like it as much as the last one because it has quite a lot of bad language.” Noga received a scholarship to Harvard at 18 but was not permitted to attend because “the paperwork had to go through Israel, who said No, no Harvard, you have to go into the Army. Now you’re commander of a sniper unit.”

In DeWitt’s work, not being able to attend Harvard is always a fateful event, the thing that, in The Last Samurai, dooms Sibylla’s father to life as a provincial motelier. Why Noga did not consider conscientious objection—the punishment for which was often a short jail sentence—during a period rife with high-profile refuseniks is not explained, but it makes the kind of empathy compelled by second-person narration far more difficult, especially from the vantage point of 2025. It also makes her less persuasive as an illustration of the preference among the world’s great powers for killing over thinking. Only one of this short chapter’s assertions felt impossible not to agree with: “When you close your eyes you see dead children”—both a disturbing echo of contemporary testimony from surgeons in Gaza that Israeli military snipers are indeed deliberately targeting kids, and an accidental commentary on the unbearable images of corpses that are today a constant presence on social media.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The Noga chapter is far from the only aside in Your Name Here whose point (and success) is unclear. DeWitt has in the past evinced some skepticism about the value of editors: not so much in their curatorial capacity, but in their ability to improve a manuscript through useful changes and comments. In an interview with the Institute for the Future of the Book, she said that an editor should be “someone with strong tastes which do NOT simply replicate mine. Someone with profound knowledge of material relevant to the book under consideration.” She doesn’t seem to think she’s met many who fit that description, but the bigger problem is that, in DeWitt’s telling, the publishing industry’s typical procedures don’t allow authors to get a full picture of their various editors’ “intellectual profiles” in advance. (“My Heart Belongs to Bertie,” a story in her Some Trick collection, depicts precisely this dilemma.) As a reader, though, it’s hard not to wonder if Your Name Here could have benefited from precisely the kind of editorial meddling she deplores.

In a way, the novel prompts this hypothetical itself. Several of the excerpts from Lotteryland featured in here concern the scheme of a down-and-out hustler named Ephraim to turn his luck around by writing a bestselling memoir (truthfulness not necessarily required). He meets a woman named Gaby with contacts in the publishing world who offers to serve as his go-between, but her friends keep turning him down, dismissing his proposals as “not interesting enough” or “insincere and calculating.” Until, that is, Ephraim has a brilliant idea: While writing, he’ll use his lottomonitor, a kind of personal computer that allows the characters in Lotteryland to enter giveaways and check highly specific odds, “to see whether each new sentence [has] maximised my chances of appealing to the maximum possible audience.” This strategy results in a series of ruthless subtractions: From his current manuscript, he takes out the lottery—the institution that most directly structures his reality and that of his readers—as well as a number of recognizably DeWittian flourishes, like “advice about maths and English” or even “talking about the book with Gaby,” a mirror of the kind of conversations that Your Name Here contains in spades.

Dispiritingly, Ephraim’s gambit appears to succeed: The most insincere and calculating version of the book is the one that finally catches publishers’ attention. This allegory of how an increasingly risk-averse industry encourages homogeneity among writers by forcing them to sand down whatever is deemed too ambitious, original, or noncommercial in their work may be unsubtle, but it is also strangely poignant. Reading it, I saw Your Name Here’s missteps and excesses—which a more traditional path to publication would have tried to stamp out—in a new light. I thought about the reader in DeWitt and Gridneff’s book with whom I had most identified: “You’re a romantic at heart. You want writers to be rebels, revolutionaries, you want them to break the machine or be broken.” It’s hard not to conclude that, right now, the machine is winning. But Your Name Here’s brokenness is a testament to the virtues of putting our bodies upon the gears.

More from The Nation

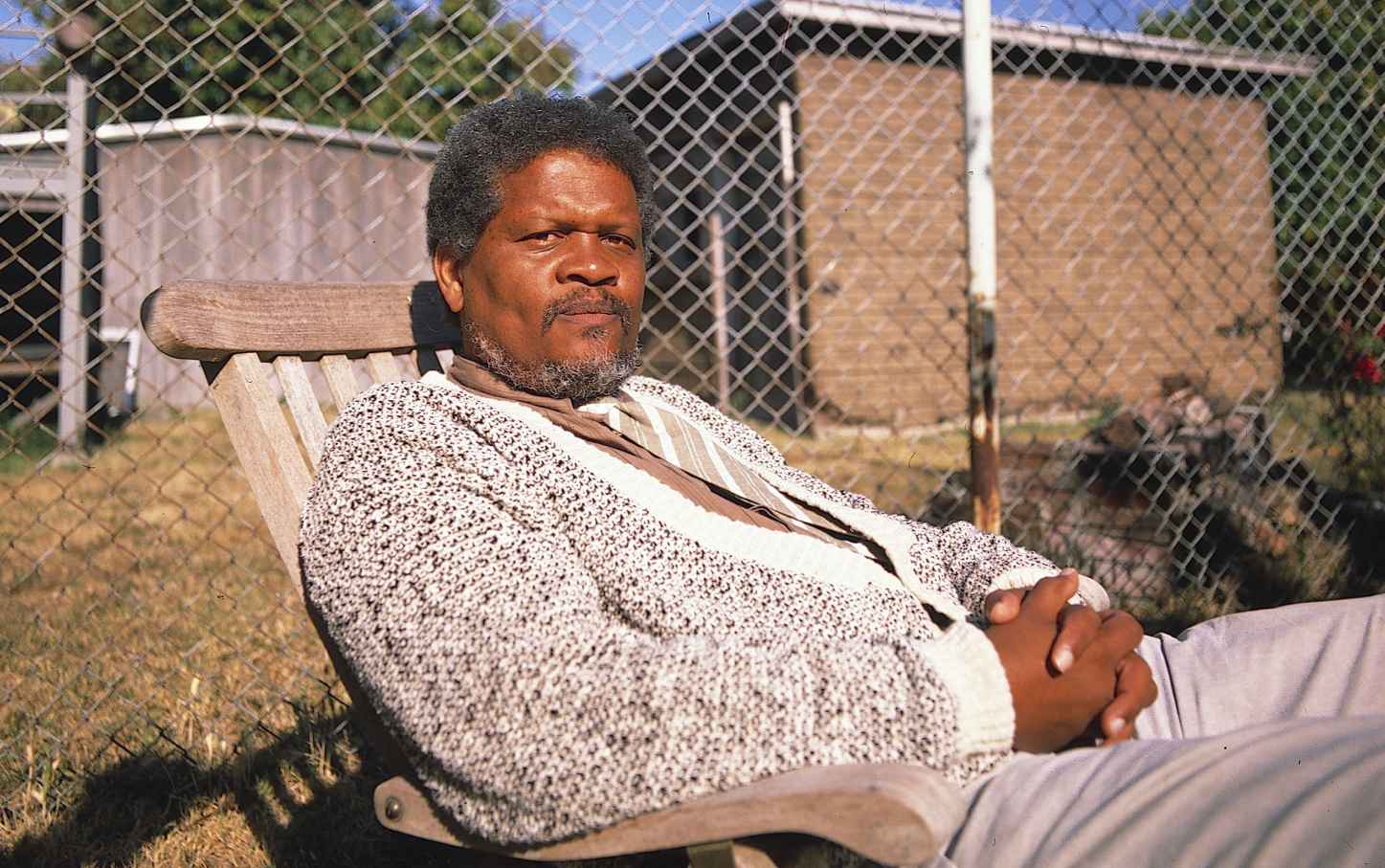

Ishmael Reed on His Diverse Inspirations Ishmael Reed on His Diverse Inspirations

The origins of the Before Columbus Foundation.

How Was Sociology Invented? How Was Sociology Invented?

A conversation with Kwame Anthony Appiah about the religious origins of social theory and his recent book Captive Gods.

How Immigration Transformed Europe’s Most Conservative Capital How Immigration Transformed Europe’s Most Conservative Capital

Madrid has changed greatly since 1975, at once opening itself to immigrants from Latin America while also doubling down on conservative politics.

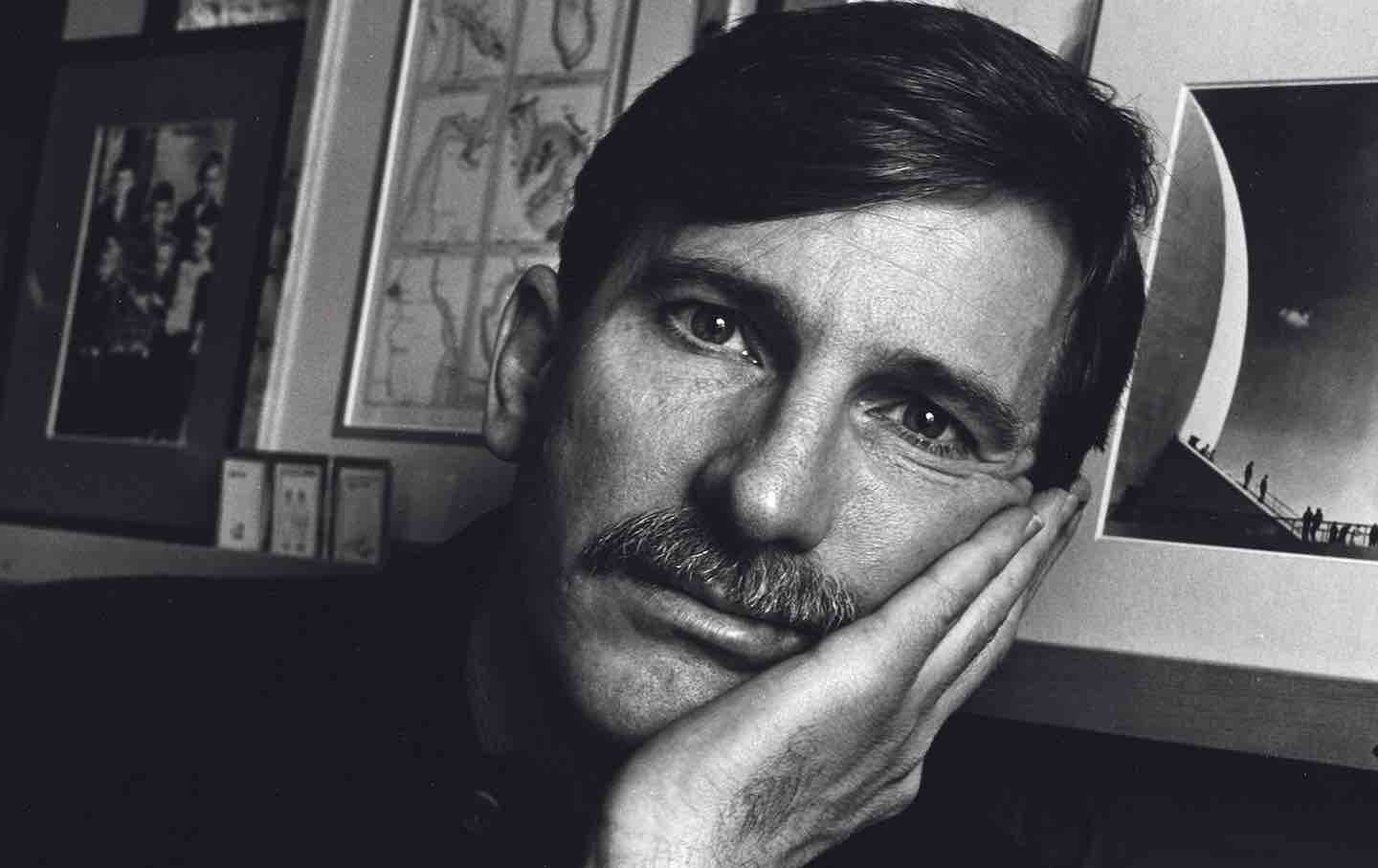

A Living Archive of Peter Hujar A Living Archive of Peter Hujar

The director Ira Sachs’s transforms an intimate interview with the photographer into a film about friendship, routine, and why we make art at all.

George Whitmore’s Unsparing Queer Fiction George Whitmore’s Unsparing Queer Fiction

Long out of print, his novel Nebraska is an enigmatic record of queer survival in midcentury America.

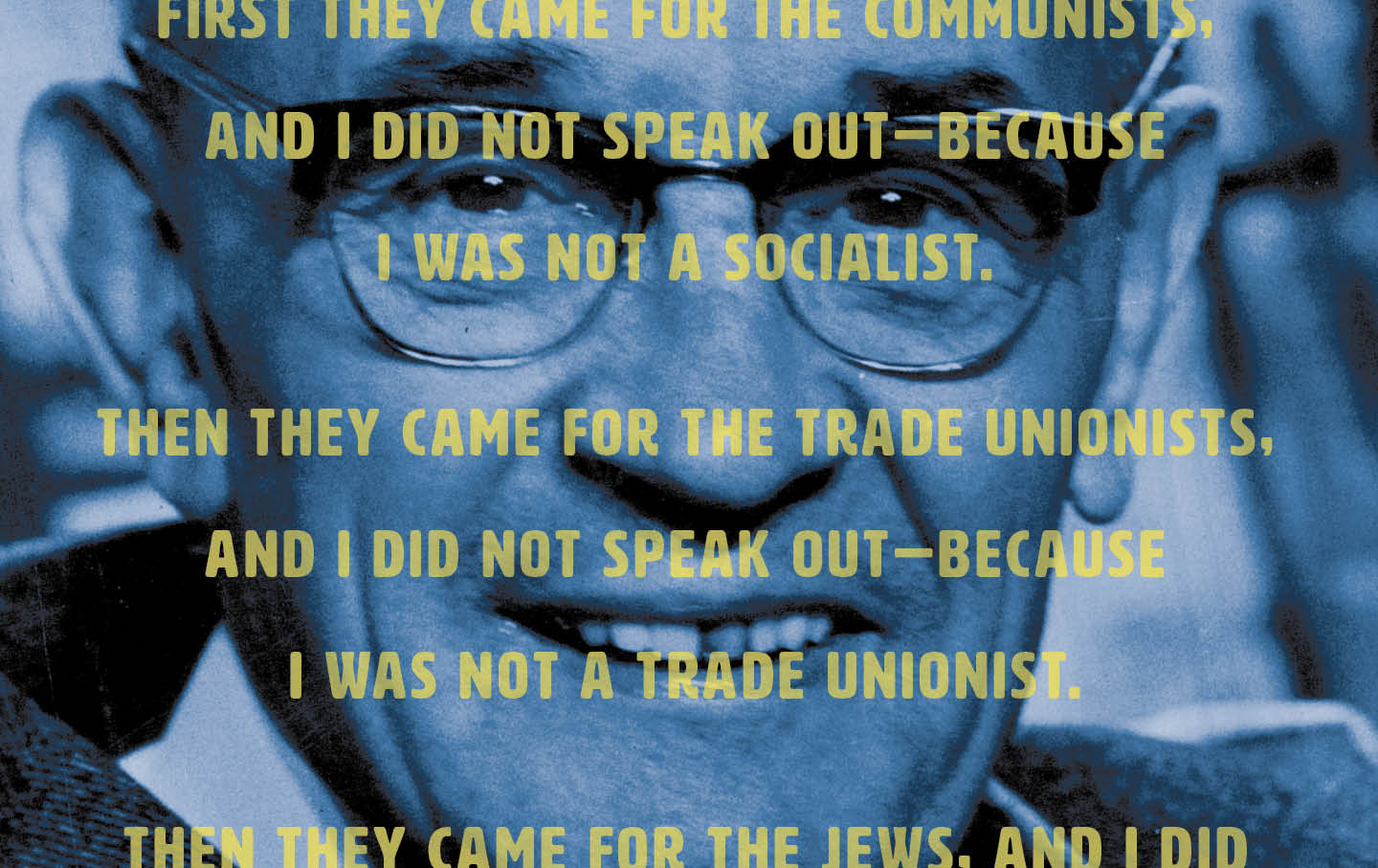

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?