The Clock

Solvej Balle’s experiments with the timeline.

Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time

The Danish novelist’s septology, On the Calculation of Volume, asks what fiction can explore when you remove one of its key characteristics—the idea of time itself.

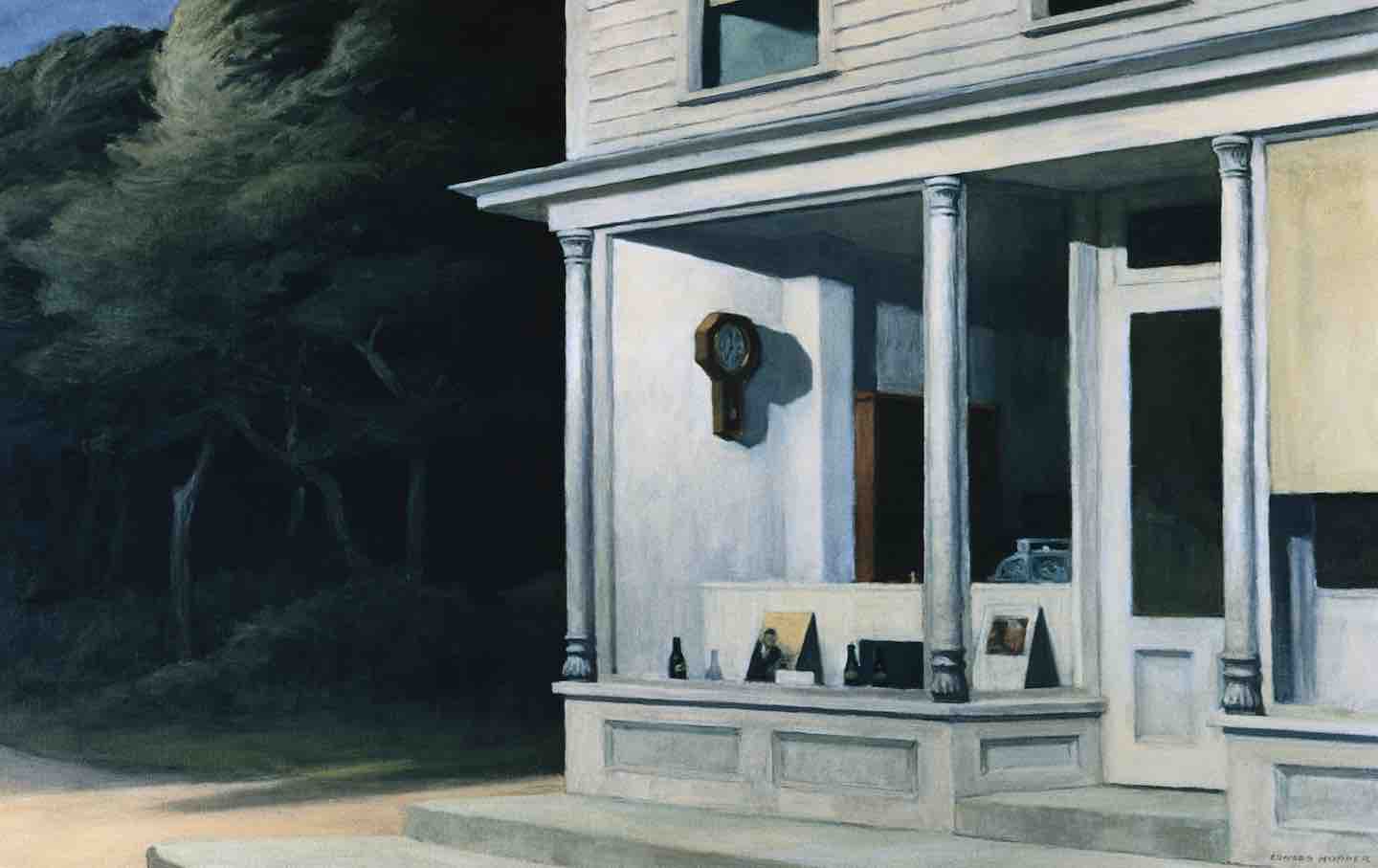

Edward Hopper, Seven A.M.

(Francis G. Mayer / Corbis / VCG via Getty Images)Without the concept of time, the fundamental principles of human experience—death, life, love, loss—could not exist, hence literature could not exist. A single day in London, kicked off by the need for flowers for a party, can unspool a narrative that moves both forward and backward to address the melancholy passage of time itself; or, alternately, a man may choose to visit a sanatorium for three weeks and leave seven years later, losing all sense of time’s passage.

This is how Soviet-era literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin diagnosed the problem of novelistic time: “Time, as it were, thickens, takes on flesh, becomes artistically visible; likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time, plot and history.” His idea of chronotope, loosely based on Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, was a name for the presence that categorized different types of literature based on how time and circumstance weave through plot. “The chronotope is the place where the knots of narrative are tied and untied. It can be said without qualification that to them belongs the meaning that shapes narrative.” What happens, then, if time ceases to exist?

Books in review

-

On the Calculation of Volume I

Buy this book -

On the Calculation of Volume II

Buy this book -

On the Calculation of Volume III

Buy this book

This is the question animating Solvej Balle’s On the Calculation of Volume, a septology of novels told from the vantage point of Tara Selter, an antiquarian bookseller forced to live through the same day, November 18, over and over again. Balle, a heavyweight in the Danish literary world since the late 1980s, has said in interviews that she came up with the idea of Calculation in 1987, six years before Groundhog Day popularized the trope of a person stuck in time. “My way of seeing Tara get older was very childish,” she told interviewer Adam Biles for Shakespeare and Company’s podcast. She proceeded to treat her own aging as “just research” before turning back to the project. Over 30 years and many drafts later, she self-published the first volume through her own press, Pelagraf, and quickly gained an audience in Denmark and abroad. Balle approaches the series through a theoretical framework not unlike Bakhtin: If time is the glue holding narrative together, what happens to a world unbound by its constraints?

Tara’s first November 18 begins when she wakes up in a hotel room in Paris, there to attend a rare books auction on behalf of her business with her partner, Thomas (the other T of their antiquarian book business, T&T Selter). When she wakes up the next morning to have breakfast in the hotel lobby, she knows something is wrong when she sees someone drop a slice of white bread and, deliberating on whether to eat it, drop it in the garbage. It is the same event, and the same person, she witnessed the morning before. From there, she goes on to see that everyone is playing out the same day in the same pattern, presumably living out their November 18 for the first time while she, Tara, is trapped.

Upon this realization, she calls Thomas before taking a train home to a fictional town in northern France called Clairon-sous-Bois. Together, they map out different possibilities and theories of what could have happened. They spend their days making love and experimenting with the new laws of this world; sometimes objects newly acquired stay and sometimes they disappear. Eggshells evaporate from the trash but the gap in the carton remains. A jar of pickles stays in the fridge but a newly purchased pair of tights disappears. Some receipts of purchases stick around the next morning while others vanish, though the money in her bank account is always renewed. Later, she realizes she can make objects stay by sleeping with them under her pillow.

After she visits her friends Philip and Marie, owners of a rare-coin shop, on the evening of her first 18, she buys an Ancient Roman coin—a sestertius depicting Emperor Antoninus Pius on one side and Annona, goddess of grain, on the other. Together, they discuss the “high demand for rare and not so rare relics of the past” that keep their businesses afloat (an early hint that Tara has always been a little unstuck from the present). The coin she buys disappears back to the shop, but it’s not the last time we will catch sight of it.

Each day, Thomas wakes up surprised to see Tara at home lying beside him and she must explain their situation anew. Writing in a notebook to keep track of the time, Tara recounts these days at home with Thomas as the happiest of her life, the confusion of their new reality blending into a fog on their gray November as Tara confronts an eternal present that Thomas pledges to accompany her on: “he made a short speech, addressed first to the books under my pillow, then to the books at the foot of the bed, asking them to stay a little while longer, and then he snuggled up close to me, put his arms around me and asked me, too, to stay till the next day, whatever day it might be, or better still, the day after that—and preferably forever, in fact.”

But eventually the haze breaks and too many days stand between them. “We were living in two different times and there was no hiding the differences,” Tara writes. Her hair and fingernails grow longer, and a burn she received on her first November 18 slowly heals into a scar; “Thomas was caught in eternity and I was slowly but surely moving towards my grave.” It’s through the dissolution of their love story that Tara’s uneasiness about the world around her starts to settle in, and her notebooks transform into a remarkably porous narrative that absorb the anxieties of modern life and time itself—supply chain shortages, globalism, and climate change, but also universally timeless fears of being alive—love, death, and mortality. These anxieties, sublimated by lack, unspool as Tara dives deeper into her day.

Mirroring the conversation she had with Philip and Marie—on the “nostalgia or hunger for history,” that define their professional lives as antiquarians—Tara will fill the void of the present by consuming herself with questions of the past.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →As weeks of November 18ths go by, the shelves of the local grocery store dwindle; the coffee and chocolate bars bought at the local grocery store remain consumed and unreplenished. When Tara picks a leek from the garden to boil with some bouillon, the leek does not grow back (“I harvest nothing. I sow nothing.”) She describes herself as a “monster” eating her world while the people living out their day without consciousness of repetition, like Thomas, are “ghosts.” She is suddenly made aware that her main presence in this world is her footprint of consumption, and so she begins her exile in the guest bedroom, hidden from having to explain herself to Thomas, who is stuck in his own “pattern.”

Lurking in their shared home, her world opens up as more details emerge—she memorizes the sound of the wind knocking a planter against the wall, Thomas’s footsteps as he pads around the house, the familiar birdcalls: “The world was porous, there were chinks in it, there was another year underneath.” Her fixation is not just subterranean; she buys a telescope and studies the heavens that move in the same pattern every evening, suspended in time (though she nearly convinces herself one night that the moon is larger than it usually is). At the conclusion of Book I, she goes back to Paris to retrace her steps on the first anniversary of her predicament, hoping that her attention to detail will reveal what thrust her into this temporal loop. Like her first November 18, she visits the coin shop again, the Roman sestertius sitting safely in its case. But this time, her friends, somewhat disturbed by her strange and desperate affect, wrap up the sestertius for her as a gift before setting her on her way.

No matter how many days she is forced to repeat, Tara is constantly bewildered, intrigued, delighted, and horrified by her material world. “I get it into my head that there is someone who wants something of me and that what they want of me is not good,” she writes when roaming the streets of Paris. When plotting how to store leftovers that will be able to stay with her overnight, she imagines the fridge to be laughing alongside her: “It just stood there, upright, emitting its stuttering, almost sobbing laugh.” If time helps create stories, perhaps it is objects themselves that act as interlocutors by its absence.

In Book II, Tara resolves to experience seasons for herself, first by forcing an early Christmas onto her family, then by traveling through Europe to experience glimmers of winter, spring, and summer; there’s snow to be found in the North, beach weather to be found in the South. After she twists her ankle outside of a cafe in Odense, she strikes up a conversation in the hospital waiting room with a meteorologist, who, believing she is scouting potential shooting locations for a movie, advises her on where she might find various microclimates to suit her needs.

With a database of weather, Tara eats winter soups in Norway, visits spring lambs in Cornwall that, given the increasingly warm weather (in one of the book’s subtle nods to climate change), are now being bred in autumn, and finds summer in Montpellier. The concept of seasons is put into question by the meteorologist: “She saw them more as psychological phenomena. Memory concentrates. Accepted stereotypes. Conglomerates of experiences and feelings, perhaps.” Upon entering a grocery store in London, Tara is struck by the “seasonal havoc” forced upon the contemporary shopper—berries, vegetables, and international cuisines on offer. Indeed, one of the primary anxieties that Balle intersects with time’s ceasing to move concerns the fact that our lives already seem out of sorts with the world’s natural rhythm: Food is grown artificially year-round, and human labor is required to distribute it. Tara’s fears invoke a whole community of people she no longer can reach; she swallows the supply chain.

The artifices that comprise her world spur her journey onward: If the concept of seasons can be remade in a single day according to location, what else can be regained in her reality? It is partly this question that eventually causes Tara to gaze upon her coin with newfound suspicion: “I felt this growing awareness of the coin on the countertop. A coin that wants something of me, I thought, although coins don’t, of course, lie around wanting anything of anyone.” From there, an obsession develops, and she dedicates her waking hours to learning about the ancients. “And now I too have been smitten. A coin gone astray and suddenly I am seized by the urge to know more. About Annona and Antoninus. About the Romans and their boundaries. About gods and emperors, coins and the grain trade.” Walking along the Rhine, which formed the northernmost border of the Roman empire, she thinks of how they’ve been with her all along. If time is a container, she thinks, so is empire, so are cities, the aqueducts, the vessels they crafted to make olive oil. Since time has stopped moving in a forward direction, she’s gone sideways in search of seasons and then goes backward in search of the past; how deep of a container is she in?

When she starts attending lectures on the Roman empire at a university in Dusseldorf, she meets a man named Henry Dale who is also stuck in time, marking the end of Book II and beginning of Book III. Henry Dale, much like Tara, dwells in the humanities as a sociology professor. We learn that he’s spent his years of November 18ths rewriting a paper he was meant to present the following day, reading Dante, and visiting his 5-year-old son in Ithaca, New York. Together, he and Tara embark on a meandering set of days in which they contemplate history and civilization. In one of their first conversations after he moves in with her, they talk about their mutual recently acquired affinity for the Roman Empire:

When you inhabit the same day for so long, you start to see all the cracks. There’s nowhere to hide anymore. We have come to a standstill in a time that is starting to crumble. Europe in free fall. The final days of the West. It’s no wonder one feels compelled to follow in the Romans’ footsteps. One wants to know what led them to their downfall.

But for Tara, it is not history itself but the objects that fall out of history that move her: “I had traveled through history, watching battles play out, but I kept stopping at a loaf of bread, a building, a glass.”

Despite being trapped within the confines of November 18, Tara wakes up, goes to bed, night turns to morning, and, ultimately, time passes. Her hair grows long (Balle has said that she has grown her hair out alongside Tara while writing the septology) and she notices new lines on her face. When Henry leaves to go back to Ithaca, Tara goes back to Clairon-sous-Bois to listen to Thomas while she hides in the guestroom. The gushing of pipes as a toilet flushes, the sound of a shower, the teakettle whistling are all sublimated as familiar sounds of longing, a remnant of her connection to Thomas; he lives in his day while she listens.

Even so, there’s always depth to the pattern, layers to peel back:

Until today, I have only heard the gush of water in the pipes when Thomas was in the shower, a trickle down the drain. I have heard his movements whisper through the house. A hand or a sleeve brushing a wall. Urine, water, and toothpaste through the pipes. Footsteps across the floor before he goes to bed. But now I can hear him singing. He sounds happy.

This passage is reminiscent of the penultimate chapter of Ulysses (a novel Balle has cited as an influence), where Leopold Bloom turns on a faucet in order to fill his kettle to boil water. Beyond his comprehension, the narrative zooms outward to a reservoir in Wicklow from where this water derives, tracing its journey through the pipes of Dublin. All of Ireland is working at that moment to bring him water for his hot cocoa. It’s a passage of connection that binds Bloom, despite the isolated nature in which he spends his day, to the nation of Ireland as a whole. Could it be that, despite the solitude Tara seeks in the guest bedroom, the sounds of Thomas (boiling water, flushing the toilet, showering) connect them not only to each other but to the world at large?

Perhaps if there were an omniscient narrator, they too would have shown us the system of pipes that create the sounds of the house, or the supply chain that affords her orange-flavored chocolate. But Balle presents us with a more gradual becoming in the discoveries of her world, contained within first-person narration. But by the end of the third volume, there’s a key shift: Tara and Henry have met fellow travelers. Tara’s insular musings (“There is no healing to be found in sentences, they disintegrate, there is garbage and roses, stray notes which curl up and disappear. There are open windows, breadless birds, lost routines”) become reanimated with the arrival of a new set of characters.

Upon meeting a teenager named Olga, she writes, “Her sentences bled into mine, and I could feel the words gradually coming back to life, the sentences began to take shape again, my own sentences too—or ones resembling those I used to say.” Like time itself, which she describes as, “the edges of lawns or like weeds, or hedges and flower beds and things that merge together or overshadow each other as they grow,” Tara’s narrative begins to absorb the voices around her.

We might look at the novel as its own container; it’s enclosed in Tara’s notebook, after all. After three novels of inquiry, Tara’s subjectivity gives way to a collective. Suddenly, the container has expanded into a chorus of anxiety. Together, she and her fellow travelers may construct their own form of time, finding themselves, once again, among the living.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

Barbara Pym’s Archaic England Barbara Pym’s Archaic England

In the novelist’s work, she mocks English culture’s nostalgia, revealing what lies beneath the country’s obsession with its heritage.

Why We’re Still Fighting Over Elgin’s Marbles Why We’re Still Fighting Over Elgin’s Marbles

In A.E. Stallings’s Frieze Frame, the poet retells the many conflicts, political and cultural, the ransacked portion of the Parthenon has inspired.

Is it Too Late to Save Hollywood? Is it Too Late to Save Hollywood?

A conversation with A.S. Hamrah about the dispiriting state of the movie business in the post-Covid era.

The Melania in “Melania” Likes Her Gilded Cage Just Fine The Melania in “Melania” Likes Her Gilded Cage Just Fine

The $45 million advertorial abounds in unintended ironies.

Nobody Knows “The Bluest Eye” Nobody Knows “The Bluest Eye”

Toni Morrison’s debut novel might be her most misunderstood.

Melania at the Multiplex Melania at the Multiplex

Packaging a $75 million bribe from Jeff Bezos as a vapid, content-challenged biopic.