Why Is Yoko Ono Still Misunderstood?

A recent biography helps shed light on her life before and after John Lennon—making a case for the primacy of her art and its lasting influence.

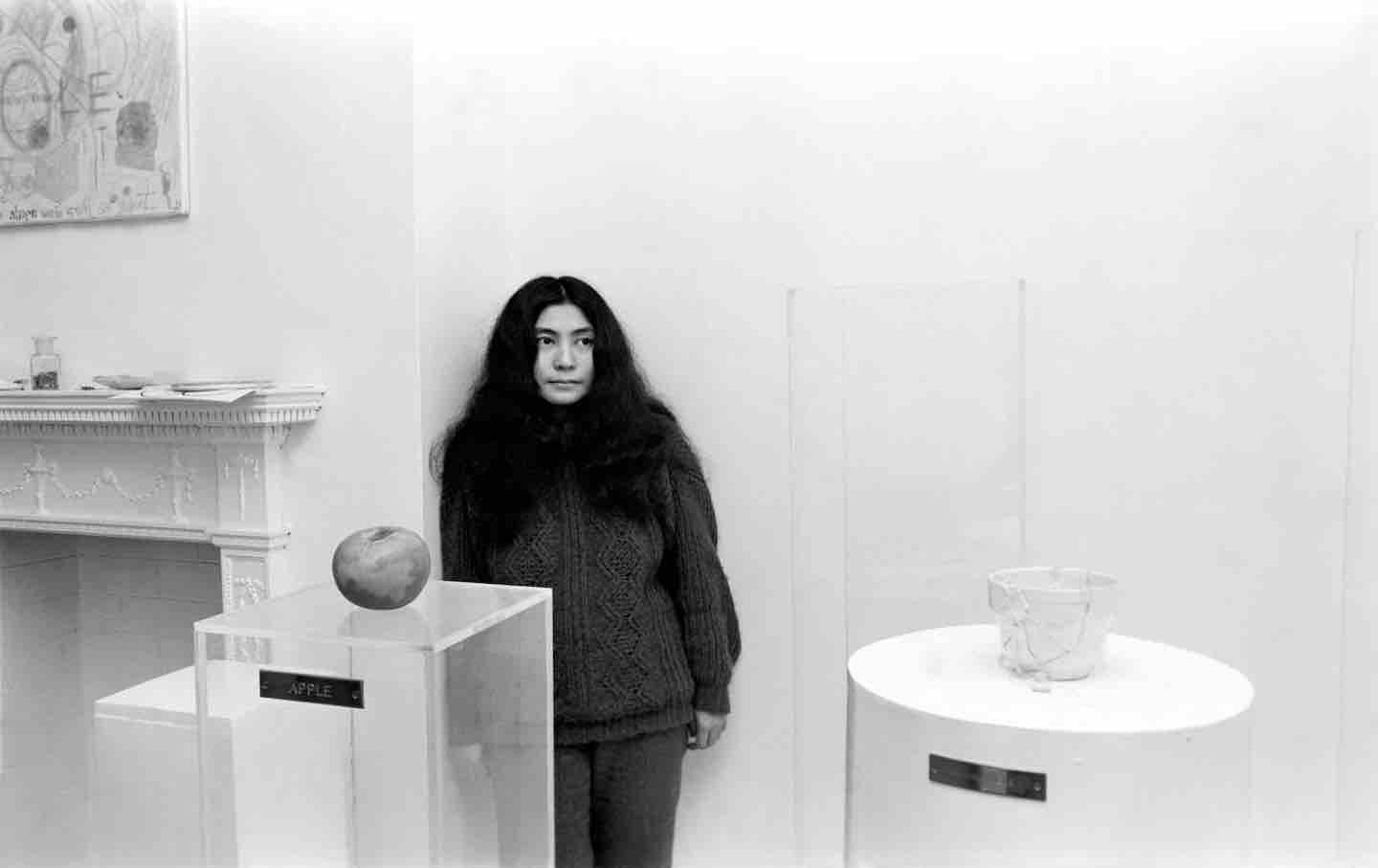

Yoko Ono, 1967.

(Watford / Mirrorpix / Mirrorpix via Getty Images)

On March 9, 1945, as bombs fell on Tokyo and air raid sirens blared in every corner of the city, a 12-year-old Yoko Ono was bedridden with fever. Unable to be taken to a bomb shelter by her mother, Ono watched the deadly explosions light up the sky from her bedroom window.

Books in review

Yoko: A Biography

Buy this bookTwenty years later, in March 1965, Ono was performing a work titled Cut Piece at New York’s Carnegie Recital Hall. The 32-year-old artist sat onstage in the deferential seiza position, a pair of scissors at her side. The audience was invited to come one at a time and snip off a piece of her all-black ensemble. People were initially shy, trimming away a hem, a sleeve. But a group of young men started hacking away at her skirt and sweater. Ono became more exposed. The men kept getting back in line. Finally, one sliced her bra strap, and Ono quietly called for the curtain.

David Sheff invokes these anecdotes at the top of Yoko, his new biography of the 92-year-old artist, musician, and activist, to establish the forces that shaped her life—vulnerability and violence, darkness and serenity. In the summer of 1980, Sheff spent three weeks with Ono and her husband, John Lennon, to write an article for Playboy. On December 8, less than 24 hours after Sheff’s profile hit the newsstands, Lennon was dead, shot on the street in front of his apartment building, the Dakota, with Ono at his side. Sheff and Ono had grown close during the reporting process, and he visited her in the aftermath of Lennon’s murder. Their families remained intimate: Ono was the unnamed “old family friend” who opened her home to Sheff’s troubled son, as the author described in his 2008 memoir, Beautiful Boy (which was later adapted into a movie starring Timothée Chalamet and Steve Carell).

Written with the cooperation of family members, ex-partners, and longtime friends, Yoko is a comprehensive biography of the much-misunderstood artist. But Ono’s rich life could—and should—fill a book much longer than these 287 pages. Sheff grapples with his subject’s complexities from a polite distance and offers little critical analysis of Ono’s visual art, and even less of her music. After half the book is spent focusing on Ono and Lennon’s 14 years together, it’s a bit jarring when the next 45 years of Ono’s life fly by like a highlight reel of collaborations, retrospectives, and successes. Somewhere within these pages, though, is the portrait of an uncompromising woman defined by contradictions: an heiress making anti-elitist art, a pacifist defined by a horrific act of violence, a celebrity artist whose work invites her audience to tune inward to the music of their own minds. If anything, a book this readable emphasizes Ono’s radicalness and resistance to compromise.

Born in 1933 into a powerful Japanese banking family, Yoko Ono wanted for little, except perhaps parental affection. Ono’s mother, Isoko, was preoccupied with society life; her father, Eisuke, had dreamed of becoming a concert pianist before capitulating to the family trade. He was absent for significant chunks of Ono’s childhood and was interned in Hanoi during the war. After the Tokyo firebombings, Isoko and her three children evacuated to a farming village in March of 1945. The circumstances of their privileged life changed dramatically during the final months of the war, and Ono was tasked with bartering and foraging for food. She encouraged her malnourished siblings to imagine magnificent feasts, which her younger brother, Kei, later called her “first conceptual art piece.”

From a young age, Ono was trained to be an artist—studying piano, calligraphy, and painting. Her father encouraged her to pursue opera training because, as Ono recalled him saying, “For women it’s an easier thing to do—to sing somebody else’s songs.” But Ono resisted this path and enrolled at the elite Gakushuin University in 1952, becoming the first female student in the philosophy department. She soon grew tired of the program’s curriculum, which she felt was “theoretical—cold and dead,” and dropped out. She joined her family in New York, where her father was working for a time, and enrolled in Sarah Lawrence College in the mid-1950s.

Ono initially thrived in this comparatively progressive environment, publishing poetry in the college newspaper and studying the 12-tone compositions of Arnold Schoenberg. But she still felt misunderstood. “Whenever I wrote a poem, they said it was too long, it was like a short story; a novel was like a short story, and a short story was like a poem,” she said in 1971. “I felt that I was like a misfit in every medium.” Awoken one morning by chirping birds, Ono was reminded of a preschool assignment to translate the sounds of nature into musical notation. While struggling to track the birdsong, Ono realized that limitations can lead to liberation: “If you wished to bring in the beauty of natural sounds into music, suddenly you noticed that the traditional way we scored music in the West was not the way,” she said. “So I decided to combine notes with instructions.”

Ono dropped out of Sarah Lawrence in 1956 and, against her parents’ wishes, married Toshi Ichiyanagi, a Juilliard-trained pianist. They became fixtures in a downtown avant-garde music scene that orbited around Morton Feldman and John Cage, who taught an experimental composition class at the New School attended by Ichiyanagi. Cage’s musical and philosophical ideas regarding duration, silence, and chance gave Ono confidence “that the direction I was going in was not crazy.” In 1960, Ono decided that she and her peers needed a space to show their work and began renting a bare-bones loft at 112 Chambers Street. Alongside the minimalist composer La Monte Young, she curated a series of concerts and performances that attracted art-world luminaries like Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Isamu Noguchi, and Peggy Guggenheim.

Ono never headlined a show at the loft—though she did perform her works at the concerts of others—and was sometimes treated with condescension by her male peers. So she was understandably frustrated when George Maciunas, an architect and designer who’d attended several loft performances, decided to start his own series. The two quickly mended fences after Maciunas offered Ono a solo show at the AG Gallery, and from there her career as a conceptual artist began in earnest. July 1961’s “Paintings & Drawings by Yoko Ono” featured interactive conceptual works that disrupted the relationship between audience and artist, including Painting to Be Stepped On—a piece of canvas that audiences were invited to tread across. Ono would later resist Maciunas’s efforts to associate her with Fluxus, an artistic movement that valued the process over the product—she had no desire to belong to a group. “I was not interested in just smashing a piano or a car or something. I was interested in the delicate way that things change—in that kind of destruction, which, in a way, is more dangerous,” she later recalled.

Ono held her first solo concert in November 1961 at Carnegie Recital Hall, a 299-seat auditorium attached to the renowned venue. She included a version of “A Grapefruit in the World of Park,” a poem-performance adapted from a story Ono first published at Sarah Lawrence. Onstage, artists and musicians including Young, Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, and Jonas Mekas performed a variety of mundane acts: eating, smashing dishes, tearing newspapers. A pair of men conjoined by rope tried to move silently across the stage, a tough task considering that tin cans were tied to their legs. A toilet intermittently flushed somewhere offstage. The performance concluded with the debut of Ono’s now-famous vocalizations: Her idiosyncratic “sixteen-track voice” blended Schoenbergian operatics, Tibetan and Indian vocalizations, breathwork, throat singing, silence, and hetai, a Kabuki singing style that incorporates deliberate vocal straining into arresting, wordless intonations. According to an “alternately stupefied and aroused” Jill Johnston in The Village Voice, Ono’s “many tones of pain and pleasure mixed with a jibberish of foreign-sounding language that was no language at all.”

Ono’s work was frequently received with confusion. The positive reaction that Cage received during a 1962 tour of Japan—Ono was among the performing musicians—exacerbated her sense of alienation, as did her parents’ horrified reaction to her work. “Who was I beyond Toshi’s wife and John Cage’s friend?” she later reflected. She attempted suicide that same year and was placed in a psychiatric institution in Japan. During her stay, she received an American visitor named Anthony Cox, who knew Young and Ichiyanagi and had seen Ono’s work in an anthology of avant-garde art. Cox helped Ono get discharged, and they began dating. Though her divorce from Ichiyanagi had not yet been finalized, Ono married Cox and gave birth to her first child, Kyoko, in 1963. The young family soon moved to London.

Cox, a multidisciplinary artist with a job in advertising, encouraged Ono to monetize her works. Though she “felt it was a form of compromise to objectify,” Cox explained in a letter to Sheff, he was “more pragmatic: I wanted to create objects we could sell to support our family.” Cox facilitated the publication of 1964’s Grapefruit, a small, square book composed of works like “Blood Piece” from 1960: “Use your blood to paint / keep painting until you faint. (a) / keep painting until you die. (b).” Cox “wanted it to be both of us,” Ono later said. “All I wanted was someone who would be interested in my work.”

In 1966, Ono met John Lennon while installing a solo show at London’s Indica Gallery, and he was tickled by her optimistic sense of humor. “Everything that was supposedly interesting was all negative,” Lennon said of the art scene in London at the time. “It was all anti, anti, anti. Anti-art, arti-establishment.” Intrigued, Lennon took part in Ono’s show and climbed atop the ladder that was part of the interactive installation Ceiling Painting (or Yes Painting), then peered through a magnifying glass hanging from the ceiling to examine one tiny word: yes. Just that simple affirmation “made me stay in a gallery full of apples and nails,” Lennon said. He and Ono bonded over art, philosophy, painful childhoods, and splintering marriages. “We saw each other’s loneliness,” she reflected years later.

Ono and Lennon’s relationship was an evolving collaboration from the day they met. Their first musical project, Two Virgins, was a sound collage created the night they consummated their relationship. Their passion is evident on a song like “John & Yoko” from 1969’s Wedding Album, which consists of the pair vocalizing each other’s names in whispers and shouts over the sound of their own heartbeats. Lennon began bringing his more outré impulses—and the woman who encouraged them—into the Beatles’ rehearsals. Ono’s ubiquity in the studio and perceived influence on Lennon’s creative direction were villainized after the band broke up. She faced horrific racism and sexism and continues to be cast as the destroyer of marriages and male musical friendships, a cruel irony for an artist synonymous with peace. But Sheff makes the case that Ono’s presence—humorous, charming, benign—helped the Beatles stay together long enough to complete Let It Be and Abbey Road. “John had a foot out the door. If he hadn’t had Yoko, the other foot might have followed sooner than it did,” he writes.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →When she wasn’t sitting on an amp, minding her business, Ono focused on experimental filmmaking. Back in 1966, she made several conceptual shorts based on the instructions in Grapefruit—a blinking eye, a burning match. Most notable was Film No. 4, a tightly cropped series of buttocks that later evolved into an 80-minute film documenting approximately 200 rear ends as their owners walked on a treadmill. (Ono called the film “an aimless petition signed by people with their anuses!”) There were more theoretical works too, such as Film No. 1 (Fly) (1970), which meditates on objectification as the titular insect crawls across a nude female body.

Ono divorced Cox and married Lennon in 1969. By the early 1970s, the couple were living in New York and increasingly involved in the anti-war movement, performing at a fundraiser for anti-racism activist John Sinclair and making macrobiotic food with Black Panther Bobby Seale on late-night television. The FBI and the Immigration and Naturalization Service took notice and attempted to use Lennon’s 1968 cannabis-possession misdemeanor charge as grounds for his deportation. (Lennon ultimately received his green card in 1976.)

While Lennon lavished praise on Ono in interviews, he didn’t always treat her as an equal. Despite Ono’s contribution of concepts and lyrics to 1971’s “Imagine,” she only received a songwriting credit in 2017. In 1980, Lennon admitted to Sheff that he wasn’t “man enough” to acknowledge Ono’s contributions. Ono later described herself as “castrated” by the magnitude of Lennon’s celebrity, and his mainstream audience also had little interest in her art. The October 1973 opening of her first solo museum show, which featured Lennon as a guest artist and happened to fall on his birthday, drew a crowd that broke down the door in the hopes of a Beatles reunion.

Ono needed space, so she suggested that Lennon find a lover. Conveniently, she had a candidate in mind: their 22-year-old personal assistant May Pang. Sheff writes that “John’s lost weekend is well documented, but Yoko’s experience over that period has mostly been ignored.” But the author adds little to the narrative, describing Ono’s side of the 18-month separation in a vague, prosaic style (“She saw friends—musicians and artists, mostly”). The feminist liberation that courses through Ono’s two 1973 albums, Approximately Infinite Universe and Feeling the Space, is more revealing. “And all of us live under the mercy of male society / Thinking that their want is our need,” Ono sings on “What a Bastard the World Is.” Pang’s perspective is noticeably absent too, despite her offering plenty of material in a 2022 documentary. Eventually, Ono allowed Lennon to come home and soon became pregnant, giving birth to the couple’s only child, Sean, in 1975.

Ono and Lennon were in the midst of a fruitful collaborative period when the biography’s central tragedy occurred. Sheff’s firsthand recollections of the darkness and paranoia that consumed Ono after Lennon’s death are among the book’s most revealing. Ono spent $1 million on security in 1981, as razor blades and a copy of the couple’s 1980 album Double Fantasy riddled with bullet holes arrived in the mail. Gun-toting guards patrolled the halls of the Dakota, while inside Ono’s apartment, assistants pilfered all sorts of personal ephemera, including Lennon’s diaries. “I don’t know why, was getting so good with us,” Ono sings on 1981’s Season of Glass, her first solo album following the murder. “You bastards!” she shouts. “Hate us! Hate me! We had everything!”

Sheff loses sight of Ono as she emerges from the long shadow of Lennon’s death. Surrounded by an entourage of friends and employees—with the lines often blurring—Ono disappeared behind a stream of projects honoring her late husband’s legacy. The latter portion of the book makes frequent use of interviews from three loved ones: her son, Sean; her decorator turned partner, Sam Havadtoy; and her daughter, Kyoko, who reunited with Ono in the early 1990s after vanishing with Cox following a custody battle in 1971. (The pair spent years living as members of a religious cult.) Rarely do we hear from Ono herself in this period; while compelling glimpses into her psyche do exist, Sheff is seemingly uninterested in psychoanalyzing his subject and his friend. Sheff asks in the book’s intro, “Can a journalist tell the truth about a friend?” Here’s something of an answer.

After a nearly 20-year absence, Ono returned to the art world in the late 1980s. Her participation in a Cincinnati gallery’s tribute to John Cage opened the door to showing her new work, and she was given a modest retrospective at the Whitney in 1989 and then a critically acclaimed 2000 retrospective at New York’s Japan Society Gallery. Her musical reassessment began with 1992’s Onobox, a comprehensive six-disc collection of records from 1968 to 1985. By the time of her 2015 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Ono had been recognized as a pioneering feminist and activist who used art as a force for change in ways both conceptual and concrete.

Lennon once referred to Ono as the “most famous unknown artist. Everybody knows her name, but nobody knows what she does.” In a sense, this is still true, even though today her contributions are more readily recognized. But to many, Yoko Ono will forever exist as a shorthand for domineering women and divisive outsiders. She remains a misfit in every medium, both as an artist and an individual, still determined to induce others toward openness. “Instead of giving the audience what the artist chooses to give,” Ono once wrote of Cut Piece, “the artist gives what the audience chooses to take.”

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

Barbara Pym’s Archaic England Barbara Pym’s Archaic England

In the novelist’s work, she mocks English culture’s nostalgia, revealing what lies beneath the country’s obsession with its heritage.

Why We’re Still Fighting Over Elgin’s Marbles Why We’re Still Fighting Over Elgin’s Marbles

In A.E. Stallings’s Frieze Frame, the poet retells the many conflicts, political and cultural, the ransacked portion of the Parthenon has inspired.

Is it Too Late to Save Hollywood? Is it Too Late to Save Hollywood?

A conversation with A.S. Hamrah about the dispiriting state of the movie business in the post-Covid era.

The Melania in “Melania” Likes Her Gilded Cage Just Fine The Melania in “Melania” Likes Her Gilded Cage Just Fine

The $45 million advertorial abounds in unintended ironies.

Nobody Knows “The Bluest Eye” Nobody Knows “The Bluest Eye”

Toni Morrison’s debut novel might be her most misunderstood.

Melania at the Multiplex Melania at the Multiplex

Packaging a $75 million bribe from Jeff Bezos as a vapid, content-challenged biopic.