Thomas Mallon’s Theory of the Diary

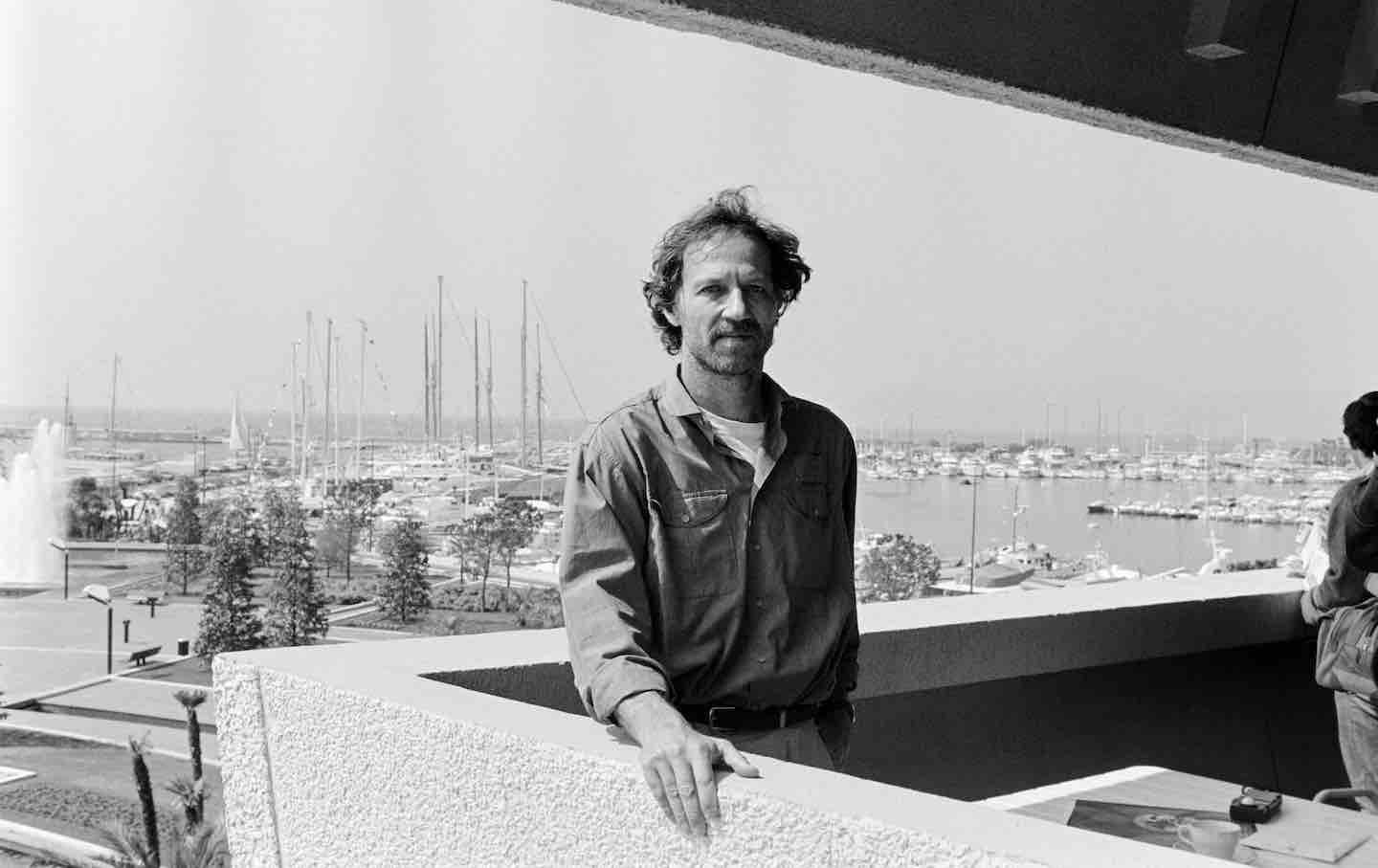

The New York writer and editor’s diaries of the AIDS era presents a curious case of what we are supposed to expect from private documents that become historical sources.

Photo by Ann Imbrie

(Photo by Ann Imbrie / Courtesy of Knopf)

Before they become historical documents, diaries start out as ordinary ledgers, a frame-by-frame accounting of the moments and events of a person’s days. With the help of time, scholarship, and critical interest, they become history in miniature, an up-close look at how a life was formed and shaped by the times the diarist lived in. One could read Randy Shilts’s monumental 1987 history And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic to learn about the infuriating and chaotic early history of the crisis: the recalcitrant politicians who saw gays as undesirables, the government’s early indifference, and the drama of the scientists forced to plead for funding to finance the research for a cure. But to see those years from a more intimately detailed human angle, one must turn to personal accounts.

Books in review

The Very Heart of It: New York Diaries, 1983-1994

Buy this book“Every day people walk down Fifth Avenue past dozens and dozens of men who are HIV+, on AZT, and fighting steadily for their lives,” Thomas Mallon wrote in his diary on March 5, 1991. “They are a city within a city, and they are invisible.”

Mallon’s AIDS-era diaries, The Very Heart of It: New York Diaries, 1983–1994, capture this invisible city in an uncertain and frightening moment. The journals are the detailed daily accounting of a young, hopeful gay man finding his way as a writer during the AIDS crisis. Many of the entries are snapshots of a vibrant life situated too closely to death, of someone fighting to keep his spirit alive during the plague years.

“We’ve all been exposed, we’re all living under the sword, & I’m not more lethal than anyone else,” Mallon wrote in 1985. “We’re either going to get it or not. Period.” Yet having accepted his fate with his right hand, Mallon bargained with the universe with his left: He wanted at least 10 more years so he could write more books.

The publication of these diaries brings full circle Mallon’s lifelong interest in such works. His second work of nonfiction, A Book of One’s Own: People and Their Diaries (1984), surveyed significant diarists throughout history, from Samuel Pepys to Anne Frank to Sylvia Plath. The diary is “the poor man’s art,” Mallon observed, and he believed these records of ordinary experience could be as compelling as “musings on great events.”

Yet while the diaries contained in The Very Heart of It do offer the reader one person’s experience of a great event—i.e., the AIDS crisis—they’re also an account of ambition, love, and work, offering a glimpse of a now mostly vanished literary milieu in New York City. What is fascinating about Mallon’s life as he tells it is the tension it holds: It contains just as much excess as it does abstemiousness. It is just as much about the fear of living as a gay man during the AIDS crisis as it is a story about professional success and all that comes with it during the highs of the late 1980s and early ’90s from his perch in the then-glamorous print media.

Today, Mallon, 73, is the author of 11 works of fiction (mostly politically oriented literary historical novels), four books of nonfiction, and two essay collections. But as it turns out, his life’s largest and longest-running work is his diaries. The Library of Congress recently acquired an astonishing 146 volumes of them, along with Mallon’s other papers and correspondence, with entries starting in the early 1970s and continuing apace until 2022. His journals are of particular interest to historians, said Sherri Sheu from the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, because they “give a day-by-day, first-person account of someone who was on the ground during the HIV/AIDS epidemic.”

In 1983, when this portion of his diaries begins, Mallon was a 32-year-old associate professor of English at Vassar on the verge of getting tenure. His second book, the abovementioned survey of historical diaries, was about to be published. That year, he decided to move from Poughkeepsie to a tiny midtown Manhattan studio on East 43rd Street, the better to absorb the energy of the city, and promptly fell in love with New York.

Mallon’s diaries from these years teem with optimism and literary ambition (an academic who aspired to become a full-time writer, he worked on book reviews on his Metro North commute to Poughkeepsie to make his big-city rent), although they’re also tempered by a constant thrum of anxiety: over the death of his lover, the classicist Thomas Curley, from AIDS, his own exposure to the virus, and the fate of his friends, who were also highly at risk. Amid his accounts of the internecine warfare of faculty meetings and his celebrity sightings around town (he was new enough to the city to delight in spotting Jackie O.), we see how Mallon struggled to achieve intimacy in his relationships with men in a frightening new world where sex was now a dangerous act.

Certain that he had been exposed to the virus by Curley, Mallon nevertheless refused to get tested in fear of receiving his own death sentence: “I wondered if, when he made love to me, he was literally killing me,” Mallon wrote in 1984. Yet in spite of everything, Mallon lived his life the way it was meant to be lived by the young and ambitious in New York City. His entries note his attendance at countless movies and plays, book parties, and dinners. Nights included the ballet, “Dignity” masses (a service for gay Catholics), the New York Philharmonic orchestra, and the opera. He watched Mets games and Dynasty. Some entries capture the fleeting moments of everyday life so adeptly that they almost read like poetry: After he saw a helium balloon slip from a little boy’s hand on a Manhattan sidewalk, Mallon recorded that “I made a run and a leap for it & almost got it.”

These happy snatches of daily life were constantly undercut by anxiety: Every summer cold and sore throat threw him into a state of panic, and each new headline about the epidemic filled him with dread. After reading an article in The New York Times in 1988, Mallon wondered if he would join the quarter-million who at the time were forecast to die of AIDS. “I tell myself I only want to finish these 2 books—let me see them done & out & then I’ll go quietly,” he wrote. “That’s what I tell myself, anyway.” This was how Mallon reckoned with the realization that, without knowing his true status, the time he had left might be limited.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In 1989, when Mallon met the artist and designer Bill Bodenschatz—who would become the love of his life—he was devastated to learn that his new partner had already tested positive. The couple’s life together was alarmingly bittersweet: How much time did they have left? And how quickly could medical science catch up with the disease? (A happy note communicated via the book’s dedication is that Bodenschatz survived his HIV diagnosis, and the couple remains together more than 30 years later.) In 1990, a year after they met, Mallon finally decided to get tested for AIDS, after six years of refusing. The result was negative. Upon receiving the news over the phone, Mallon fell to his knees, wept, and thanked God.

Before he met Bodenschatz, Mallon had chronicled a number of “casual encounters” that consisted of “brief, embarrassed” conversations about health before the act and the safe, “careful” sex that followed. The mornings after were often filled with anxiety, self-recrimination, and short-lived vows of celibacy. Ironically, by the time Mallon found true intimacy, he had lost the desire for sex, which he now associated with death. With Bodenschatz, “I am delighted to report that I think less about sex than I have in years,” he wrote.

Politics flicker steadily in the background of the diaries, hardly a surprising subject in a gay man’s account of the 1980s and early ’90s. But at a time when most gay men were raging against Republican administrations for not being responsive enough to the AIDS crisis, Mallon identified himself as politically conservative and a devout Catholic. Though he couldn’t quite bring himself to vote for Ronald Reagan or Walter Mondale in 1984, he made up for that moment of indecision by voting for the closeted conservative Democrat Ed Koch (who was widely criticized by gays for how he handled the AIDS crisis), as well as Rudolph Giuliani (whose record on AIDS is not one to be admired) and George H.W. Bush (twice) in later mayoral and presidential elections. (Bush’s stance on the epidemic was best described as a “kinder, gentler indifference.”)

“It ain’t easy being a gay neoconservative,” Mallon lamented in an entry describing the souring of his relationship with National Review in the aftermath of then-editor William F. Buckley Jr.’s now-infamous 1986 op-ed, which called for every gay man who tested positive for AIDS to be tattooed on the buttocks as a means of preventing further infection. (In the later years of the diary, Mallon also reports that he received a $100,000 advance to ghostwrite the autobiography of Dan Quayle, Bush’s famously featherbrained vice president, who once opined that homosexuality “is more of a choice than a biological situation” and added that it is “a wrong choice.”

Despite all this, Mallon rarely examines or comments on the inconsistency of being a gay man who pledges fealty to a political party that openly despised men like him. Frustratingly, it’s also impossible to learn here why Mallon is a conservative—other than that he is a staunch anti-communist—because the diaries remain eternally in the present and reveal little of his background.

As the years passed, Mallon (an admitted workaholic) wrote more criticism and published more books, earning a respectable stature in the New York literary world. He was pals with the writer Mary McCarthy, his mentor turned close friend, as well as Elizabeth Hardwick and the poet Anne Carson. In 1991, Mallon landed a job as GQ’s literary editor and wrote a book column for the magazine called “Doubting Thomas.” Suddenly, his days were less motivated by fear—AZT was helping people now, including Bodenschatz—and more by lunches with writers and publishers at the Algonquin and the Four Seasons, dinners at the Century Club, and the whirl of countless parties. (At one point, he worried that all the fine dining would give him gout.)

A diary can offer several different histories, and Mallon’s position as a bookish insider in the New York literary world creates an ad hoc social history of a time and place when the going was good. From his perch, Mallon indulged in gossip laced with a somewhat cruel sense of humor, casually eviscerating many of the lit-world bigs that he worked and socialized with. Norman Mailer is a “pompous, old, overrated bore,” while Susan Sontag is a “thumping bore.” After attending a party for William S. Burroughs, Mallon described the aging writer as “a bewildered old street person.” Ted Hughes is “gorgeous & mean & no wonder two of his wives killed themselves,” while the esteemed photographer Richard Avedon “should be a passport photographer, or a coroner’s.” Gore Vidal—whom Mallon wrangled, with much effort, into writing a GQ cover story on Bill Clinton for $10,000—is a “huge, pleasant ruin—vastly overweight in the middle, but still vain about himself.”

Mallon’s thinking on the diary as an artistic vehicle was hammered out long before the publication of his own journals. While most diarists would not admit to keeping a private journal in the hopes of its eventual public consumption, Mallon posited in A Book of One’s Own that after reading hundreds of them, he was quite sure that “no one ever kept a diary just for himself.” We should look, then, at Mallon’s diaries the same way: He always meant for us to read them, even as he was writing them.

This urge to communicate with an assumed future reader sometimes breaks through in the entries—for example, when Mallon addresses the reader directly on August 7, 1985:

Again I have the impulse to write down how nobody reading this book should ever think I didn’t feel alive. Here I was joyful, sorrowful, excited, amazed & always fully alive.… If anything happens to me, remember that.

The diarist maintains the rigor of recording the days to ensure that their life’s most important moments—from the banal to the brutal to the beautiful—won’t be forgotten. But if it’s true, as Mallon posits, that no one ever writes a diary without intending for it to be read, then the diarist doesn’t want to be forgotten, either. (And if you’re in the right position, you can always ensure this by publishing the diary yourself.)

As a self-portrait, Mallon’s diary isn’t entirely flattering, whether this was intended or not—it is as much an account of his social climbing and literary striving as it is an account of living through a public health crisis. The guy we meet in these journals can be as petty as he is witty, a relentless careerist who seems a little too invested in the trappings of New York’s high-end literary society. Mallon spends pages, for example, obsessing over the many reviews of his own books. (Eventually, his career would be kicked into high gear after a rave review from John Updike in The New Yorker.) At times, the diary reads like Making It, Norman Podhoretz’s unabashed account of his own literary hustling. In that book, Podhoretz chronicles the raw ambition and intense self-discipline that propelled his ascent, from his humble beginnings in Brooklyn (Mallon grew up on Long Island) to his Ivy League student days (Mallon attended Brown and Harvard) to, ultimately, his success as a writer and critic, which earned him a place among the influential left-wing intellectual Jewish elite of the 1960s. (Mallon, however, retains more of a sense of humor.)

What is unique about Mallon’s diary is that, in his reckoning as a gay man with the darkest days of the AIDS crisis, he never saw himself as either a victim or a capital-S survivor. Nor did he view his sexual identity as something incompatible with his politics or religion. “I believe in God and believe He wants me to make love to men,” Mallon notes at one point. “Why should that be so hard?”

Throughout The Very Heart of It, Mallon isn’t always the protagonist you might want, or expect, him to be. Such is the messiness of our diaries. One of the lessons we can learn from this chronicle, though, is that while the time we still have left before us is always unknown, the diarist gets a new chance every day to set their life down on the page, to create a proof of their existence. And in that way, the diary affords its author the one thing that many ordinary and extraordinary people alike have yearned for, no matter what times they lived in: immortality, or something like it.

More from The Nation

Can the Dictionary Keep Up? Can the Dictionary Keep Up?

In Stefan Fatsis’s capacious, and at times score-settling, personal history of the reference book, he reveals what the dictionary can still tell us about language in modern life

Why We Misunderstand the Chinese Internet Why We Misunderstand the Chinese Internet

Journalist Yi-Ling Liu’s The Wall Dancers traces how the Internet affected daily life in China, showing how similar this corner of the Web is to the one experienced in the West.

The Bad Vibes of “Wuthering Heights” The Bad Vibes of “Wuthering Heights”

Keeping its distance from the novel, Emerald Fennell’s film ends up offering us a mirror of our own times.

Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class? Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class?

Claire Baglin’s bracing On the Clock gives its readers a close look at work behind the fry station, and in the process asks what experiences are missing from mainstream letters.

Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction

The German auteur’s recent book presents a strange, idiosyncratic vision of the concept of “truth,” one that defines how he sees the world and his art.

Do Humans Really Understand the World’s Disorderly Rivers? Do Humans Really Understand the World’s Disorderly Rivers?

In James C. Scott’s last book, In Praise of Floods, he questions the limits of human hegemony and our misplaced sense that we have any control over the Earth’s depleted watershed....