How Capitalism Survives

According to John Cassidy’s century-spanning history Capitalism and Its Critics, the system lives on because of its antagonists.

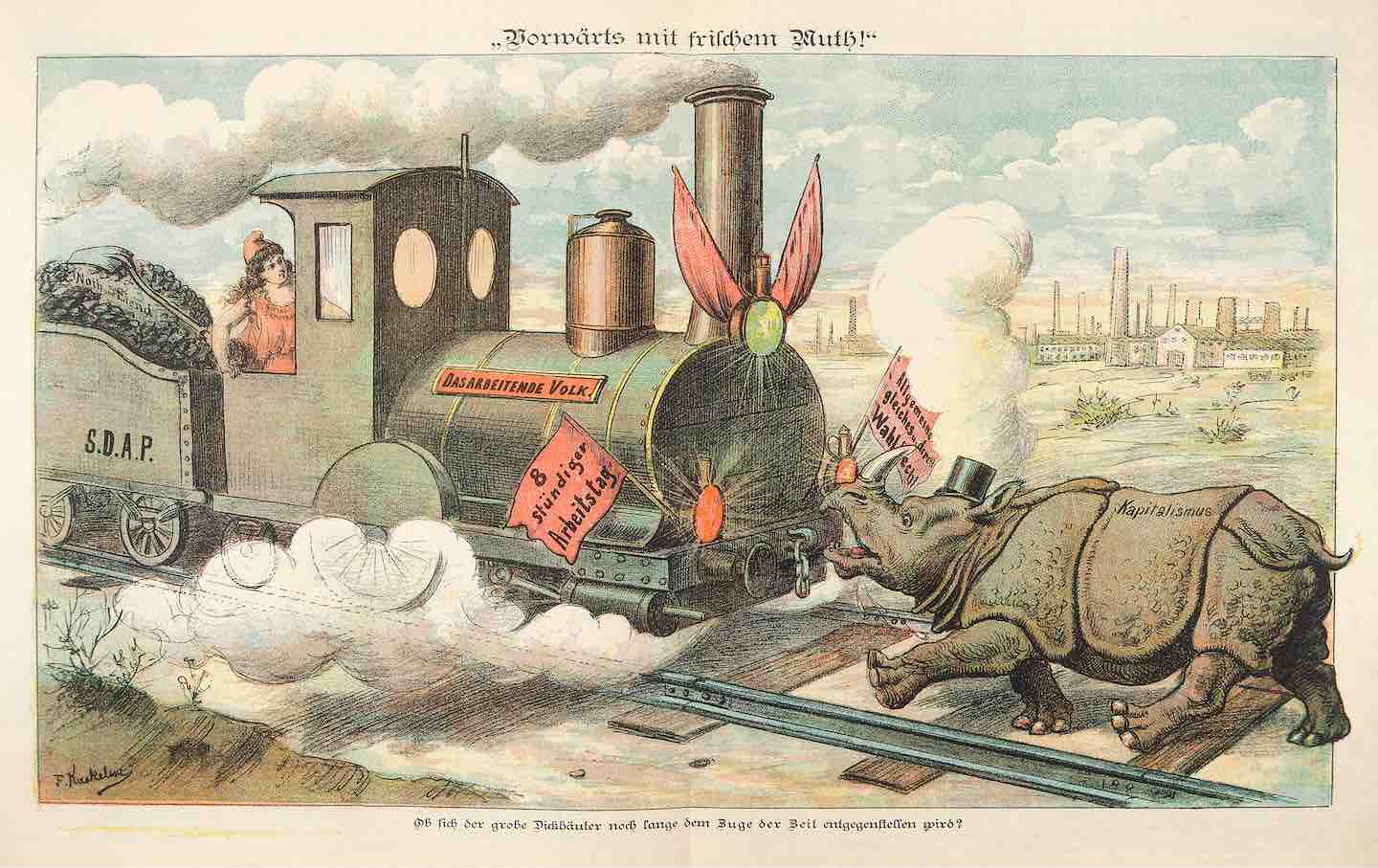

A Social Democratic leaflet against capitalism, 1905.

(Imagno / Getty Images)

In 2008, on the precipice of the global financial crisis, the British journalist Philip Delves Broughton published a book recounting his experience studying at Harvard Business School. The subtitle of his book, issued in the United States under the title What They Teach You at Harvard Business School, christened the venerable institution “the cauldron of capitalism.” Broughton’s memoir painted a devastating portrait of the American business elite: at once complacent and overworked, self-satisfied and spiritually diseased, and walled off from any evidence that contravened its belief that its members were not just exceedingly clever but also making the world a better place.

Books in review

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History From the Industrial Revolution to AI

Buy this bookThese days, however, doubt is bubbling up from the cauldron of capitalism. Global economic inequality, the rise of the right in both hemispheres, and the specter of climate change will be on the business-school syllabus whether one likes it or not. In 2023, toward the end of the Biden administration, a Harvard Business School blog published a post titled “Capitalism Faces Systemic Challenges That Require Systemic Solutions,” summarizing the research of Andy Hoffman, who insisted that “we’re watching this model die under its own weight.” A few years earlier, the prominent HBS professor Rebecca Henderson issued a guide to Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire. The New York Times was led to ask: “Have the Anticapitalists Reached Harvard Business School?”

The answer to that question, it would seem, depends on who you think counts as an anticapitalist. It is the great virtue of John Cassidy’s Capitalism and Its Critics that it shows this category to be far more capacious—and even chimerical—than one might at first assume. A New Yorker staff writer and a veteran economic journalist, Cassidy ranges over some 250 years of history unfolding on every inhabited continent to demonstrate that capitalism has been criticized from just about every vantage point imaginable. As he moves from Adam Smith and Milton Friedman to revolutionary socialists, feminists, and anti-imperialists, Cassidy’s title starts to feel like a wry joke: Capitalism’s critics, it turns out, are pretty much everyone.

Cassidy’s purpose in Capitalism and Its Critics is less to endorse any particular critique of capitalism and more to legitimize the very enterprise of criticism in the eyes of those recalcitrants who still feel squeamish about it—those who think there is no alternative. By the end of this 570-page book, Cassidy has made a persuasive case that capitalism cannot survive without policymakers and business leaders taking even quite radical objections seriously, responding to them with another turn of the wheel of capitalism’s perpetual revolution. Like a great white shark, capitalism dies if it stops moving—and the ceaseless antagonism of its critics helps ensure that it never does.

Cassidy signals his ambition to broaden our understanding of who counts as a critic of capitalism from the start of the book, which opens with a pair of chapters treating figures who rarely appear in litanies of the system’s notable enemies. First we meet William Bolts, an employee of the British East India Company in the mid-18th century who wrote a tell-all account of the corporation’s abuses after its officials cracked down on the private trading activity that Bolts and others used to enrich themselves—selling commodities on their own time and for their own gain within the company’s territory in India. While acknowledging the self-serving nature of Bolts’s complaint, Cassidy finds in his writing an ultimately clear-eyed diagnosis of the perils of monopoly power and the encroachment of big business onto the proper domain of the political sovereign. “Some of his criticisms of corporate capitalism would live on, even if they weren’t widely associated with him,” Cassidy observes, with considerable understatement.

Next up is a household name, albeit one more often reckoned in the ranks of capitalism’s greatest defenders: the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher and political economist Adam Smith. It took a long time and a fair bit of selective reading to mint a reputation for Smith as a champion (or even the “father”) of capitalism, a term not in usage during his lifetime, and Cassidy explains why. While Smith unquestionably believed that market competition—and the division of labor it engendered—fueled prosperity, he observed that the consolidation of big, monopolistic businesses like the East India Company actually interfered with the operation of the invisible hand that guided markets of small independent producers to beneficent outcomes. Smith assailed the moral hazard inherent in the limited-liability joint-stock company and denounced the “mercantilist” philosophy that the East India Company advocated, along with the violence and cruelty it inflicted on the British colonies. Smith’s worldview, Cassidy emphasizes, was pro-market but anti-corporate and, in some important respects, preindustrial.

Beginning with Bolts and Smith, and the East India Company that both men decried, helps Cassidy to clarify exactly what he means by “capitalism.” Defining capitalism is a notoriously tricky matter; it’s tempting to understand it first and foremost as a set of beliefs. That’s what people mean when they call Smith the “father of capitalism.” Framing Smith instead as a critic restores him to his proper position as just one person among countless others living in a society that was capitalist because of the way it organized production, not the ideas it had about itself. An unbridgeable gap divides any intellectual abstraction invoked to defend capitalism, like the free market or the invisible hand, from the beast itself: a material and even impersonal system; a set of social relations that often appears to us to possess a mysterious, thing-like character, as Karl Marx famously argued in the first chapter of Capital.

Perhaps you were wondering when that book would make an appearance. Over 130 pages of Capitalism and Its Critics elapse before it arrives on the scene, preceded by a range of chapters treating the early workers’ movement, the development of British utopian socialism, the relationship of socialism to other political movements (from feminism to antimodernist conservatism) and the early work of Marx’s collaborator Friedrich Engels, culminating in the Communist Manifesto they wrote together. The effect, once again, is to pluralize the category of anti-capitalism—and to distinguish it from Marxism per se. The latter, Cassidy emphasizes, was merely one entry in a vast and heterogeneous catalog of 19th-century socialisms. This point cannot escape any diligent reader of Marx and Engels, who criticized their many rivals relentlessly, but it’s still well worth making, since such readers are in short supply, and the notion that all critics of capitalism are at least latent Marxists still abounds both among the status quo’s more paranoid supporters and among Marxists overeager for allies in lonely and reactionary times.

In explaining what made Marxism distinctive, Cassidy follows the rhetorical lead of Marx and Engels themselves and foregrounds the self-consciously scientific character of their approach: their search for lawlike regularities in the system that could both explain its functioning and suggest how it might be overcome. While Marx and Engels were far from the first intellectuals to criticize the consequences of the system we now know as capitalism, they were arguably the first critics of capitalism (or the “capitalist mode of production”) to understand it as a comprehensive social system, as opposed to fixating on the different elements it expressed: monopolistic corporations, degrading technologies, greedy and abusive bosses, and so on. Cassidy gives a lucid and even sympathetic presentation of the “laws of motion” that Marx identified in Capital, walking readers through the way capitalists appropriate surplus value even without unequal exchange and the pressures of market competition that drive production toward greater scale and capital intensity. He also identifies more subtlety and complexity in Marx’s portrait of capitalism than most standard glosses admit, debunking, for example, the common notion that Marx thought working-class living standards could never improve under capitalism.

But Cassidy ultimately sees Marx’s work as no more than a “mixed bag,” its insights limited as well as enabled by its conception of capitalism as a deterministic, law-governed structure. This methodology, in Cassidy’s view, led both Marx and Engels to underestimate capitalism’s ability to weather crises through adaptation and reform, even as they presented a groundbreaking account of its perpetually self-rejuvenating character. Marx, Engels, and many of their subsequent followers, Cassidy argues, could not accept what he sees as the logical implication of their understanding of capitalism’s inherent dynamism: that it could keep mutating forever without breaking down completely. The only charge against capitalism that Cassidy treats with unadulterated skepticism is the suggestion that any of its problems are necessarily fatal. Revolution, he maintains, is a “deus ex machina,” and the one ironclad political belief he seems to evince across these pages is that reform is worthwhile for its own sake, regardless of whether it may hasten, or postpone, the end of capitalism itself.

Cassidy devotes much of the rest of Capitalism and Its Critics to theorists whom he believes better understood the potentially infinite ability of capitalism to cope with crisis, for better or worse. If capitalism has, at least to date, manifested an uncanny ability to solve its problems, those solutions have often engendered new problems in turn, especially for people who aren’t capitalists. One especially important and pernicious structure for capitalist problem-solving is imperialism. Cassidy reconstructs the development of this insight beginning with the work of John Hobson, Rosa Luxemburg, and Vladimir Lenin in the decades around the turn of the 20th century, when older forms of mercantile colonialism were giving way to a new wave of European imperialism characterized by territorial conquest and the export of capital. He traces this thread through to the era of post–Cold War globalization, highlighting the French Egyptian Marxist economist Samir Amin’s account of the role of institutions like the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund in creating and preserving access to the labor, resources, and markets of the Global South for big, monopolistic corporations from the Global North.

The major problem that imperialism solves for capitalism is its tendency to become, as Lenin put it, “overripe.” The pressures of market competition encourage the development of both labor- and capital-saving innovations, which risks the accumulation of both surplus labor and surplus capital. Surplus labor, Marx pointed out, can usefully discipline workers, but too much wage suppression deprives capitalists of the consumption power necessary to ensure that all the goods they can make can actually get sold—which means, in turn, that surplus capital has even more trouble finding profitable investment outlets. Modern imperialism, like previous forms of colonialism, can help address overproduction by what is euphemistically called “creating new markets”: in other words, converting formerly self-subsistent producers into proletarians dependent on market purchases to satisfy their needs. But it goes one step further and also enables surplus capital in the imperial core to make its way to more profitable pastures (sometimes literally) in the not-yet-overripe periphery. For this strategy to work, of course, the periphery can never fully ripen: It must remain permanently and actively “underdeveloped,” in the language of late-20th-century radical political economy. This state of underdevelopment, however, tends to create social dysfunction and oppositional agitation that can emerge as full-fledged political problems for global capitalism, in exchange for the economic ones that imperialism helps fix.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →For this reason, even a capitalist with no moral qualms about imperialism might wish for a cleaner solution to the problem of overripeness, and Cassidy observes that this is just what the great liberal economist John Maynard Keynes discovered. Keynes used the tools of mainstream economics to convince his peers that a persistent shortfall in what he called “aggregate demand”—the total amount spent throughout the economy, by both consumers and investors, on goods and services—could spiral into the kind of structural, intractable crisis represented in his time by the Great Depression. This prospect, Keynes argued, obviated the traditional arguments against major government spending, especially deficit spending. Rather, in times of crisis, he maintained, the state could and should use all policy mechanisms available to it to increase the level of aggregate demand and restore the harmonious cycle of profit, investment, production, and consumption. Keynes self-consciously sought to stabilize rather than destroy capitalism, but for the sake of that end, he was willing to endorse the redistribution of wealth from idle “rentiers” to those who would actually spend it, whether as consumers or investors in enterprises that put the unemployed to work.

That was a distressing prospect, both for those rentiers who prized their personal wealth over the long-term health of the system and for those who realized that a working class less concerned with the prospect of unemployment and penury could become rather unruly. People gripped by such distress tend to have a lot of power in modern societies, which is why the great service that Keynes offered to perform for capitalism was often refused. Cassidy recognizes that this political, rather than strictly economic, dilemma affords the best argument against the long-term viability of Keynesianism. He sympathetically profiles the Polish Marxist economist Michał Kalecki and the American socialist intellectual Paul Sweezy, both of whom offered a version of this case. He finds their warnings vindicated by the neoliberal turn that began in the 1970s, when business interests and conservative economists like Milton Friedman convinced policymakers to abandon the goal of full employment and take steps to crush the power of organized labor. There’s plenty of reason to worry that a proper Keynesian revival today, as arguably seemed possible early in the Biden years, would eventually meet the same fate.

The endless dance between reform and reaction—as opposed to its ultimate degeneration into raw right-wing tyranny—is the best that Cassidy seems to think we can hope for. He recognizes a kinship between this cycle and what the Austro-Hungarian economist Karl Polanyi called the “double movement”: the use of state power to impose what is misleadingly called a “free market” economic order and the push for “social protection” that emerges to check its depredations. The double movement was not Polanyi’s own political horizon, however. He was a socialist, and while he saw socialism as “the tendency inherent in an industrial civilization to transcend the self-regulating market by consciously subordinating it to a democratic society,” he firmly believed that this tendency could someday reach fruition in a form of political and economic life qualitatively and irrevocably beyond capitalism.

Cassidy never rules out the possibility that capitalism could, in theory, someday meet its demise. Nonetheless, although Capitalism and Its Critics at no point becomes a manifesto, Cassidy implies that it is more productive to focus on the problems of capitalism and how those problems might be solved humanely than to speculate about how we could finally supplant or overcome the system (which, after all, is why the book is called Capitalism and Its Critics and not something like Varieties of Socialism). He gives the last word to a collection of intellectuals on the “center left” who, in the wake of the global financial crisis, have sought to envision what the social-protection prong of Polanyi’s double movement could look like in our own time. Cassidy favorably summarizes, for instance, a recent proposal by the economists Samuel Bowles and Wendy Carlin to focus on “shrinking capitalism” by creating more institutions—“team-based open source” projects and “the gig economy” are among their examples—that depart from the model, as Cassidy writes, of “the traditional hierarchical capitalist firm, in which workers carried out routine, preassigned tasks for a set wage or salary.”

The entire book that precedes this account, however, works to show that the notion of “shrinking capitalism” is incoherent. Capitalism restructures, in their entirety, the societies in which it takes root. It is not merely “the economy” or “the market” or “the workplace”; it’s the whole shebang, what Marxists are fond of calling “the totality.” The state isn’t outside of it, as Kalecki understood when he predicted the demise of full-employment Keynesianism. The household isn’t outside of it, as Silvia Federici and the other anticapitalist feminists that Cassidy discusses understood, since the unpaid work that (mostly) women perform there reproduces the labor power capitalists rely on, for free. Even momentous transformations in economic policymaking merely change the shape, not the size, of capitalism, as Keynes knew very well. There was not any less capitalism in the era after World War II, when Keynes’s ideas became widely accepted, than there was when Keynes was born in 1883. In fact, there was quite a great deal more of it, precisely because, as Rosa Luxemburg argued, capitalism incessantly chews up alternative forms of life and regurgitates them as imperialist outposts.

Although Cassidy cautions that Bowles and Carlin “weren’t endorsing the pernicious practices of platform companies like Uber and Lyft,” there is a reason why those companies have been able to refashion the idea of flexible resource-sharing into a new form of exploitation. From the perspective of capitalism, any attempt to shrink, stabilize, rebalance, decentralize, or reregulate it appears to be a business opportunity. That’s why they’re excited about the proliferation of such schemes at Harvard Business School. By transforming the landscape of capitalism, they allow it to adapt to something new, which is its lifeblood. They give capitalists an exciting challenge: How will we make money from this? And without a steady supply of such challenges, capitalism will always grow stale and fragile.

Ever eager to identify surprising intellectual kinships, Cassidy suggests a potentially productive synergy between the notion of “shrinking capitalism” and the “far left” enthusiasm for “protest encampments, worker cooperatives, bartering and recycling networks, communal farms” and other “institutions and spaces that operated independently of the state and of the monolithic capitalist economy.” But when that synergy does exist, it is invariably a sign that those institutions have already failed. The commune, as radicals understand it, is not something that adds up with a shrunken capitalism to make a single society. It is a different, incommensurable society—a set of “non-manipulative social relations,” to take a phrase from the late philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre—and to that extent exists always in irresolvable antagonism with capitalism, as those communards from Paris to the present who have met their end in bloodshed have learned firsthand. Any genuinely successful attempt at getting outside capitalism inaugurates a fight to the death.

More from The Nation

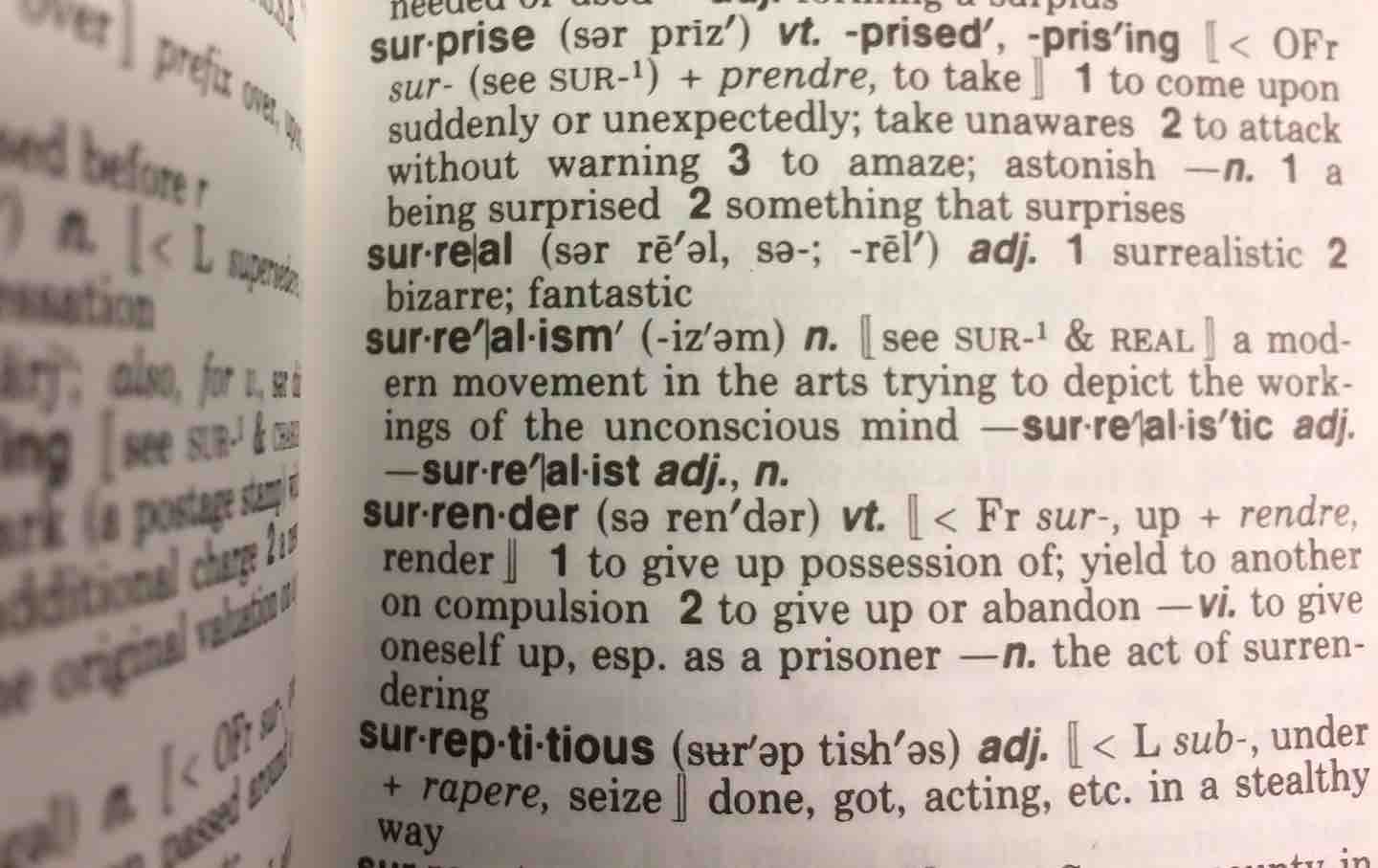

Can the Dictionary Keep Up? Can the Dictionary Keep Up?

In Stefan Fatsis’s capacious, and at times score-settling, personal history of the reference book, he reveals what the dictionary can still tell us about language in modern life

Why We Misunderstand the Chinese Internet Why We Misunderstand the Chinese Internet

Journalist Yi-Ling Liu’s The Wall Dancers traces how the Internet affected daily life in China, showing how similar this corner of the Web is to the one experienced in the West.

The Bad Vibes of “Wuthering Heights” The Bad Vibes of “Wuthering Heights”

Keeping its distance from the novel, Emerald Fennell’s film ends up offering us a mirror of our own times.

Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class? Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class?

Claire Baglin’s bracing On the Clock gives its readers a close look at work behind the fry station, and in the process asks what experiences are missing from mainstream letters.

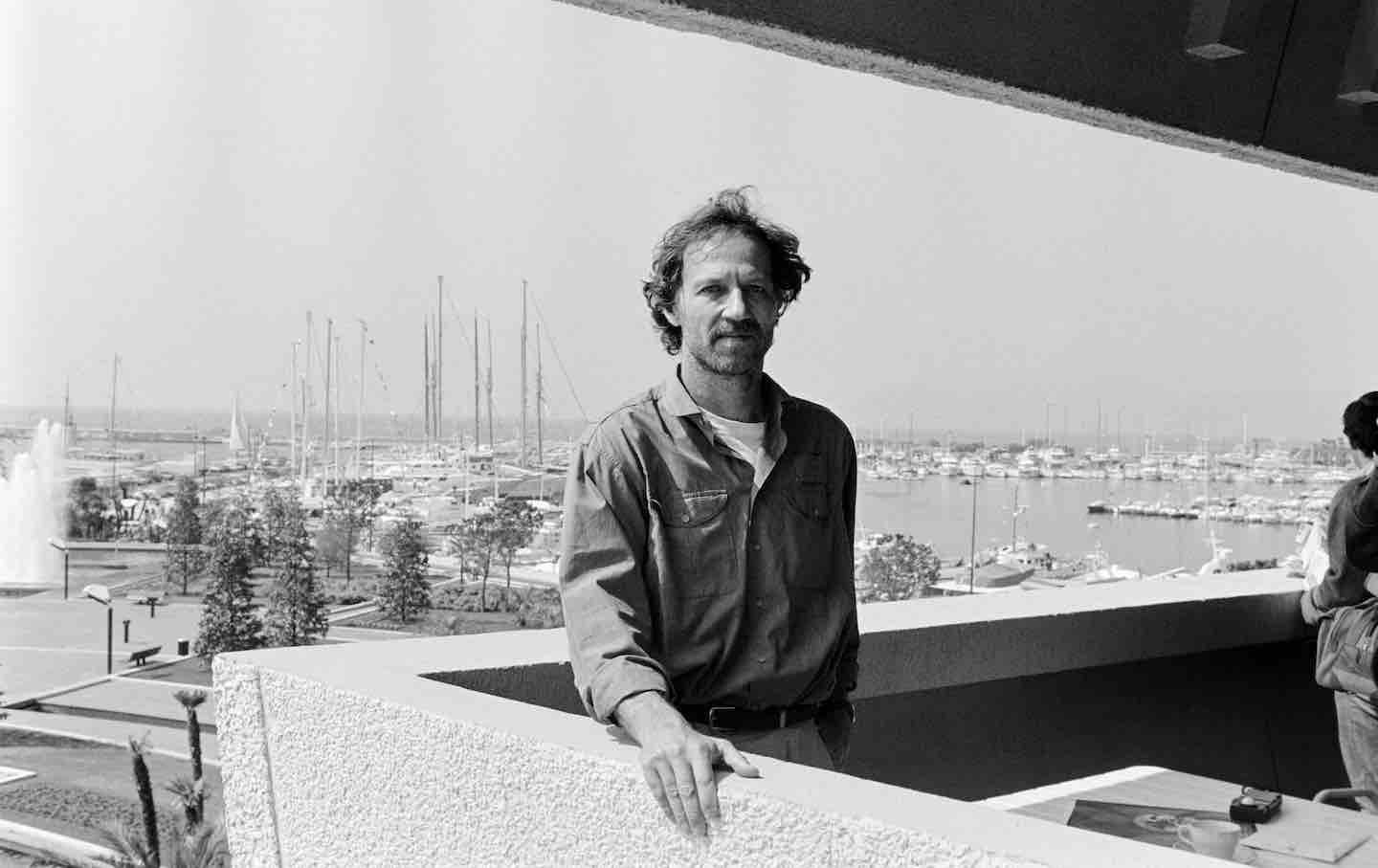

Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction

The German auteur’s recent book presents a strange, idiosyncratic vision of the concept of “truth,” one that defines how he sees the world and his art.

Do Humans Really Understand the World’s Disorderly Rivers? Do Humans Really Understand the World’s Disorderly Rivers?

In James C. Scott’s last book, In Praise of Floods, he questions the limits of human hegemony and our misplaced sense that we have any control over the Earth’s depleted watershed....