The Fight Over the Meaning of Fossils

When the remains of prehistoric creatures were discovered in Europe and the United States, it opened up a vociferous debate on the nature of time and the purpose of science.

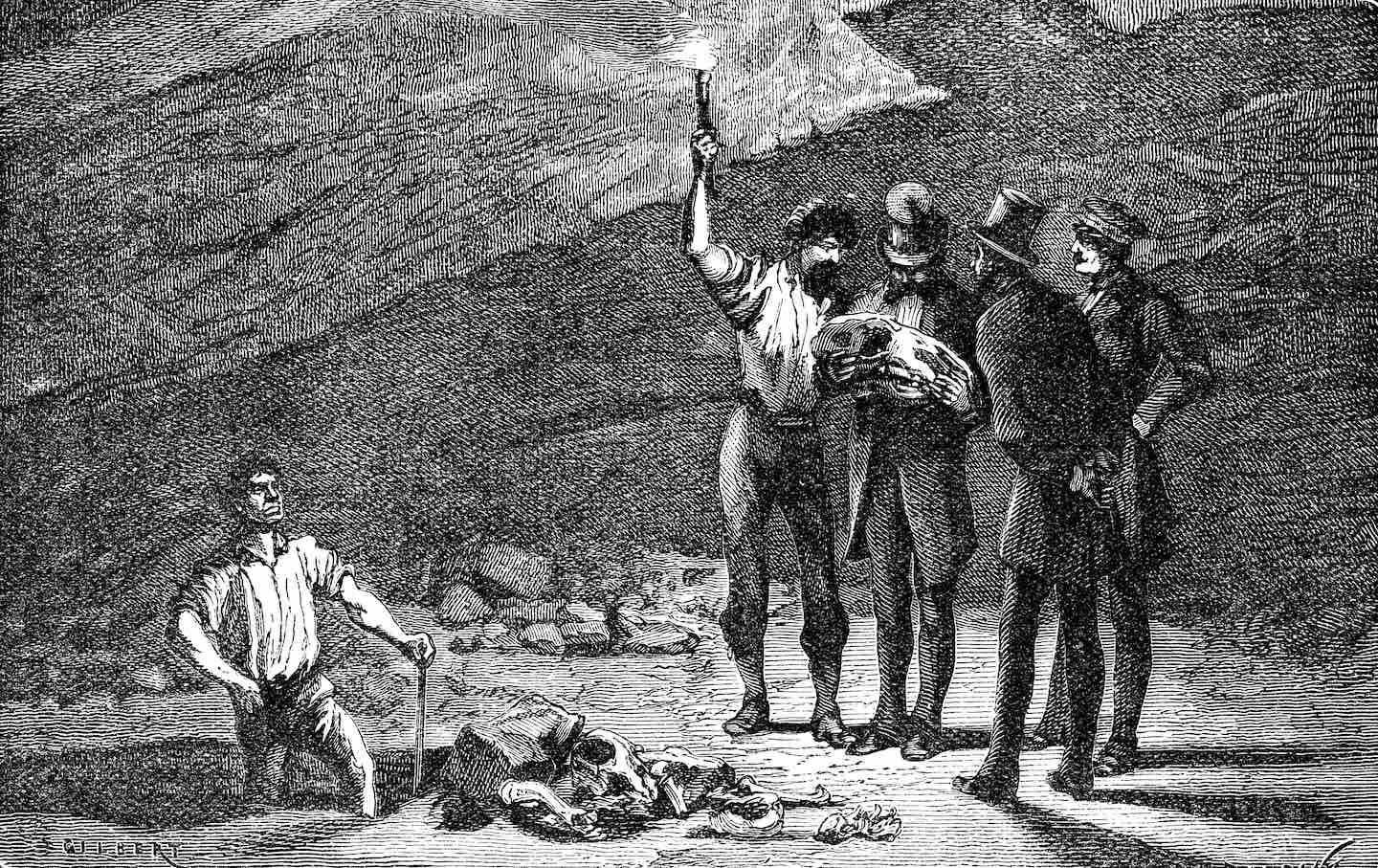

A lithograph illustrating the discovery of iguanodon fossils in Bernissart, Belgium, 1878 (c1880).

(Oxford Science Archive / Print Collector/Getty Images)The plesiosaur looked like it could have come out of folklore or ancient myth. “To the head of a Lizard,” the Oxford geologist and paleontologist William Buckland wrote in 1836, “it united the teeth of a Crocodile; a neck of enormous length, resembling the body of a Serpent: a trunk and tail having the proportions of an ordinary quadruped, the ribs of a Camelion [chameleon], and the paddles of a Whale.” First discovered in 1823 by the fossil hunter Mary Anning near Lyme Regis, a popular vacation town on the southern coast of England, plesiosaurs were unlike any living species. Yet Buckland, Anning, and other specialists who studied plesiosaur fossils in the early 19th century knew precisely what they were: the remains of extinct marine reptiles that had lived long before humans.

Books in review

-

Dinosaurs at the Dinner Party: How an Eccentric Group of Victorians Discovered Prehistoric Creatures and Accidentally Upended the World

Buy this book -

Impossible Monsters: Dinosaurs, Darwin, and the Battle Between Science and Religion

Buy this book -

How the New World Became Old: The Deep Time Revolution in America

Buy this book

This reflected a major change in the way Europeans thought about the history of the planet. The concepts of extinction and an ancient Earth weren’t new, but most naturalists had begun to accept them only relatively recently. About half a century before Anning’s discovery, in 1766 and 1780, workers in the Netherlands dug up the skull and jaws of ancient marine reptiles later named mosasaurs; experts thought the fossils belonged to whales or crocodiles. A pterosaur, or winged reptile, found in Bavaria around the same time was deemed a bird or a bat. In 1823, the general public—especially in a religiously conservative country like Britain—still largely believed that the universe was about 6,000 years old, as literalist readings of the Bible suggested. With the news of the plesiosaur—soon followed by the identification of ancient land-dwelling reptiles we now know as dinosaurs—the world no longer seemed so young.

Two recent books, Dinosaurs at the Dinner Party, by Edward Dolnick, and Impossible Monsters, by Michael Taylor, recount the sensational discovery of reptile fossils in the 1810s and 1820s in Britain, an important center for geological and paleontological research. These gigantic, outlandish creatures became beloved cultural artifacts and helped illustrate the revolutionary theories that scientists were proposing about Earth’s long prehistory. Both books stress the deeply unsettling effects of these ideas on British society. Dolnick focuses on how the discovery of dinosaurs challenged Britons’ conception of the natural world, trampling on the widespread view that it was divinely created, benevolent, and harmonious. Taylor, following the ramifications of this profound change through the Victorian era, argues that dinosaurs helped expand intellectual freedom in 19th-century Britain. He puts them at the center of debates over secularism and Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection.

In Dolnick’s and Taylor’s Whiggish accounts, science gradually triumphed over hidebound ideology and brought us closer to our current, correct view of Earth’s past. A third recent book, Caroline Winterer’s How the New World Became Old, suggests a more complicated story. She follows the “deep time revolution” in the United States, which included discoveries of important dinosaur specimens across the country. But she also reveals the ways Americans used developments in geology and paleontology to put a modern veneer on time-worn prejudices. In her telling, scientists didn’t free people from unfounded beliefs but instead introduced new ones, which were used to defend territorial expansion, racial hierarchies, and even religion itself. Together, the three books remind us that scientific truth isn’t transcendent but, as historians of science have long argued, emerges from and reflects specific social circumstances.

Mary Anning, who was born in 1799 and lived her entire life in fossil-rich Lyme Regis, came from a family of fossil hunters. Her father, a carpenter who died in 1810, sold fossils to tourists to supplement his income. In 1811, her brother Joseph found a complete fossilized skull of the marine reptile ichthyosaur; about a year later, Mary located the rest of the specimen. In addition to the ichthyosaur and plesiosaur skeletons, she also uncovered the first British pterosaur, in 1828. Despite her class, gender, lack of formal education, and religious dissension from the Church of England (she and her family were Methodists), she befriended and gained the respect of prominent geologists and paleontologists, most of whom were well-to-do gentlemen or Anglican clergymen.

At first, no one knew what to make of the Annings’ ichthyosaur, in part because of Regency Britain’s religiosity and its intellectual isolation during the Napoleonic Wars. Few were aware of the momentous work being done in Paris by the comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier. In 1796, Cuvier determined that mammoths and mastodons were distinct from living elephants and that a giant skeleton from Argentina was related to modern sloths. Cuvier held that if such huge land animals still existed, even in remote areas, Europeans would probably have heard reports of them. The best hypothesis was that they had gone extinct. Years before the ichthyosaur fossil was dug up, Cuvier also identified mosasaurs and pterodactyls as extinct reptiles.

In Britain, however, Sir Everard Home, the personal physician to King George III, spent years puzzling over the ichthyosaur. In 1819, he concluded that it resembled no known class of animal and had likely gone extinct. Home, whose anatomical knowledge was mocked by Cuvier, was wrong about aspects of the skeleton, and he was later accused of plagiarizing unrelated findings from unpublished works by his dead brother-in-law. But he was right that species could completely disappear. “Home’s conclusion was alarming,” Taylor writes, “for the very idea of extinction was thought to verge on blasphemy.” If species went extinct, did that mean humans could too? If so, what would have been the point of Creation or of Christ’s suffering?

Ichthyosaurs quickly gained companions in oblivion. At a meeting of the Geological Society of London in 1824, William Conybeare, a minister and close friend of William Buckland, described the nearly complete plesiosaur that Mary Anning had found the previous year. The same night as Conybeare’s presentation, Buckland told the society about a smattering of bones that had been dug up by Oxfordshire quarrymen and that belonged to an enormous land animal, which he named megalosaurus. Buckland overestimated its length—he guessed some 60 feet, though it’s now known to have been about half that size—and mischaracterized it as amphibious, but his account of megalosaurus was the first scientific description of a dinosaur.

More discoveries soon followed. In 1825, the doctor, geologist, and fossil collector Gideon Mantell described another huge land-dwelling reptile. Three years earlier, Mantell or his wife, Mary Ann, had found large teeth in Tilgate Forest that no one could identify. Acting on a suggestion by Cuvier, Mantell established their similarity to the teeth of iguanas. He called his creature the iguanodon—the first known herbivorous dinosaur. In 1832, he revealed another major find: the hylaeosaurus, the first known dinosaur with spikes and armor plates.

“The dinosaur discoveries were news flashes in a world unprepared to make sense of them,” Dolnick writes. “Suddenly it seemed that the familiar world had been built atop a vanished world…that had been filled with gigantic marauding creatures.”

Alongside these dramatic discoveries, members of the Geological Society undertook the highly technical classification of fossilized plants, invertebrates, and smaller vertebrates in order to create a fossil record for Great Britain. This unglamorous but important work, which helped establish the prehistoric timeline still used by scientists today, depended on recent breakthroughs in geology and paleontology—particularly the realization that the two fields were closely intertwined.

Fossils have been known since antiquity, but for centuries they were poorly understood. During the early modern period, prominent European scholars debated whether fossils had come from living things or merely looked like they had, with skeptics arguing that fossils were quirks of nature or had been created by the occult forces that Neo-Platonists thought governed earthly events. Around 1700, Edward Lhwyd, the second director of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, tried to resolve this dispute by proposing a compromise of sorts between the different theories: He argued that marine fossils were formed when the sperm of aquatic animals found their way into rocks, engendering stillborn offspring made of minerals.

When early modern naturalists did accept that fossils had once been alive, they tended to draw on Scripture, ancient history, and contemporary reports of natural anomalies. The presence of marine fossils far from the sea was frequently attributed to the biblical flood. Ice Age mammoth bones were thought to be the remains of Hannibal’s war elephants from the early third century BC. In 1677, Robert Plot, Lhwyd’s predecessor at the Ashmolean, determined after much careful study that a megalosaurus femur had come from a giant human.

It was only in the second half of the 18th century that naturalists reached a consensus on what fossils were: organic matter that had been slowly petrified while buried in the seabed, which in turn was compacted into sedimentary rock and lifted above the waterline. By the end of the century, geologists in Britain and France realized that rock strata could be identified by the fossils found in them. Common sense dictated that older strata underlay newer ones, though discontinuities often made the task of sequencing them exceptionally tricky. Visual and chemical analysis didn’t provide reliable guidance, since similar types of rock were laid down in different periods, and different types of rock could come from the same period. The most dependable method for ordering strata was to compare the fossil species they contained. As a result, species too could be arranged in a rough chronological order. For example, the limestone and shale deposits found in the cliffs of Lyme Regis, where ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs were buried, had been laid down after the earliest strata in which trilobites could be found, but before the strata in which placental mammals and birds appeared. For the first time, a detailed, evidence-based sequence of life on Earth was established.

Before the advent of radiometric dating in the 20th century, geologists dated fossils and strata in relation to one another, rather than attributing an absolute age to them. Yet it was clear to geologists that these strata had been formed long before 4004 BC, the date proposed for Creation by the Anglican bishop James Ussher in his influential, rigorously compiled biblical chronology, which was published in the 1650s. (Ussher’s dates were printed in the margins of the Church of England’s authorized Bibles from 1701 until the early 1900s.) In the late 18th century, scientists in other fields were already beginning to suspect that Earth was much older than 6,000 years. The naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, argued that the planet would have needed about 75,000 years to cool from its original molten state, based on experiments he conducted with metallic orbs at an iron foundry. A few astronomers thought the universe was millions of years old.

But it was geology and paleontology that finally “burst the limits of time,” in Cuvier’s memorable phrase. Geologists reasoned that sedimentation, compaction, and topographical change needed vast ages to occur, which meant that most fossilized animals had lived hundreds of thousands or even hundreds of millions of years ago. (The current estimate of Earth’s age—about 4.5 billion years—was first made in the 1950s and is based on the rate of decay of uranium in ancient rocks. Complex multicellular organisms are believed to have first evolved around 600 million years ago.)

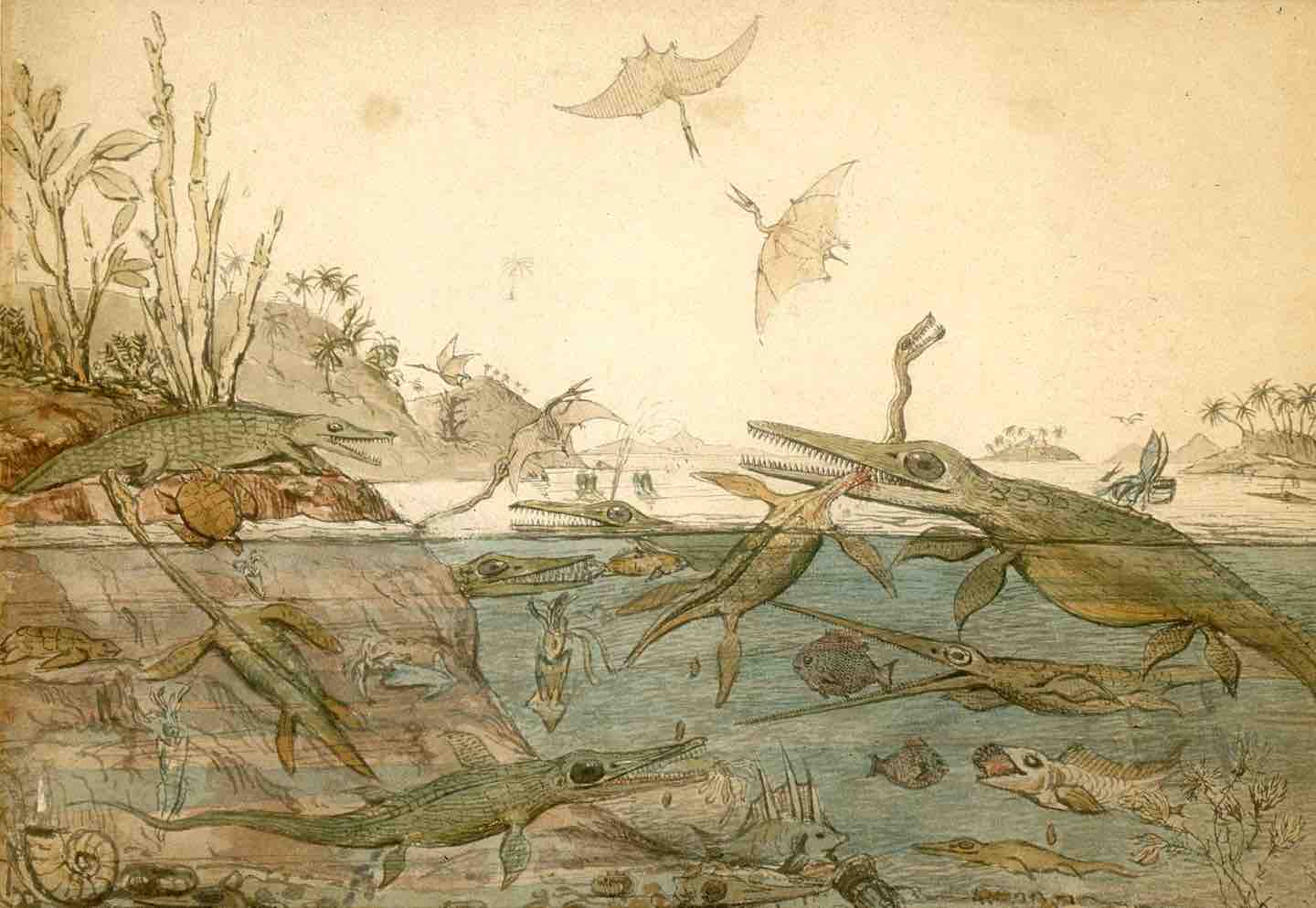

Because of the painstaking work of the Geological Society, dinosaurs and marine reptiles could be placed not only in a relative time period but in ancient habitats. In 1830, the geologist Henry de la Beche, who was also a skilled cartoonist, painted a watercolor called Duria Antiquior (A More Ancient Dorset), one of the earliest examples of paleoart, or art depicting the distant past. Proceeds from a lithograph based on the watercolor went directly to Anning, who struggled to make enough money from her fossil sales. De la Beche depicted her major discoveries—ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and pterosaurs—along the prehistoric English coast. They’re accompanied by spiral-shelled ammonites, squid-like belemnites, and other roughly contemporary marine species. The vegetation on the shore, including palms and tree ferns, was inspired by plant fossils found around Lyme Regis.

Duria Antiquior brings those old fossils to vivid life. Look closely, and you can see a plesiosaur snatching a pterosaur from the air. You can also see another plesiosaur shitting in terror as an ichthyosaur digs spiky teeth into its long neck. De la Beche included this touch as a gentle joke about Anning and Buckland, who together in 1828 had identified fossilized feces, which Buckland named coprolites. Analysis of them allowed for partial reconstruction of the diets and inner organs of ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs. Coprolites often contain distinctive fish scales and bones, and they have spiral grooves, revealing that the animals’ guts possessed the corkscrew structure still found in shark and dogfish intestines. “Coprolites,” Buckland wrote in awe, “have been interred during countless ages, until summoned from [their] deep recesses by the labours of the Geologist, to give evidence of events that passed at the bottom of the ancient seas.”

The pun on “passed” may have been intentional. Although Buckland was a minister—as all Oxbridge professors had to be at the time—and later became the dean of Westminster Abbey, he was a notorious eccentric who possessed what one biographer termed a “profane” sense of humor.

In Dinosaurs at the Dinner Party, Dolnick emphasizes the many ways that new ideas of ancient life threatened British views about nature, which were closely related to religious beliefs. The Cambridge professor William Paley, whose writings were enormously influential during the Regency and early Victorian periods, saw nature as a system perfectly designed by a benevolent God. Evidence of God’s generosity was everywhere, from the motion of the planets to the antennae of an earwig. “It is a happy world,” Paley argued. “The air, the earth, the water, teem with delighted existence.” Fish “are so happy, that they know not what to do with themselves.” Most important, “God, when he created the human species, wished their happiness.” Extinction, which implied that survival was a contest some species could lose, threatened to topple Paley’s cheery natural theology and humanity’s prized place in it.

Buckland, who defended geology and paleontology against charges of sacrilege, took pains to reconcile his work with Paley’s philosophy. Although Buckland acknowledged that the “general law of nature…bids all to eat and be eaten in their turn,” he insisted that this was done as mercifully as possible. The fearsome teeth and claws of ancient reptiles allowed them to swiftly kill their prey, which would otherwise have been “consigned to lingering and painful death” from overpopulation and famine. According to Buckland, extinction didn’t negate Paley’s depiction of nature as being full of God’s design; it was yet further proof of God’s endless ingenuity. Each species was well adapted to its role in “the great drama of universal life,” but when a species couldn’t survive changing conditions on Earth, a new, better-suited species took its place, like a software upgrade periodically released by a tech company.

Along with most English scientists of his era, Buckland held that only creative design could account for the emergence of new species. Skepticism of “transmutation,” as the French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck called his theory of the heritability of acquired characteristics, was widespread. A lingering antipathy toward the Jacobins didn’t help Lamarck’s reception across the English Channel. Conservative Britons frequently dismissed French ideas as atheistic and conducive to anarchy, and they especially detested Lamarck’s theory because it held that humans had descended from “lower” animals.

When transmutation began to gain popularity in Britain in the 1840s, Richard Owen, the country’s leading comparative anatomist, fought its spreading influence. Owen was the first to classify iguanodon, megalosaurus, and hylaeosaurus as a distinct biological group, for which he coined the word dinosaur (meaning “terrible lizard”). He believed that species followed a handful of general plans, which he called “archetypes.” Archetypes weren’t ancestors; they didn’t exist anywhere in the physical world. But they were nonetheless insuperable, ensuring that humans would have no kinship with mollusks or earthworms. His theory was the last great effort in British science to explain the variety of the animal kingdom through divine agency rather than material forces. “What Darwin had seen,” Dolnick writes, “was that there could be design without a designer.” Owen didn’t see it. He held out against evolution until his death in 1892.

Dolnick ends Dinosaurs at the Dinner Party with one of Owen’s great triumphs: the commission of sculptures of prehistoric creatures, designed after Owen’s reconstructions of them, for the relocation of the Crystal Palace to South London in 1853, two years after the world’s fair for which the palace had been built. The sculptor who worked with him, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, arranged a banquet for scientists and other luminaries in the half-completed body of an iguanodon. (Hawkins’s statues still stand in Crystal Palace Park in Bromley, but Owen’s reconstructions are far from what scientists now think the dinosaurs looked like, based on more complete specimens.) Dolnick speculates that after the banquet, Owen must have felt “complacent.” The frightening concepts raised by the discovery of ancient reptiles had been “vanquished, the corridors of time had been tidied up, and…most important of all, humankind still occupied its old, exalted position…. Everything led up to us.”

At the time of the iguanodon party, Darwin was best known for his memoirs of his voyage on the HMS Beagle and his meticulous studies of barnacles. Within a decade, his stature in British science had eclipsed Owen’s.

Alfred Russel Wallace’s 1858 essay on species adaptation prompted Darwin to hastily compose On the Origin of Species, after accumulating evidence for his theory of natural selection over two decades. Dinosaurs didn’t figure in the first edition of Origin; Darwin worried that the fossil record offered the “gravest objection” to evolution, since there were too many gaps between species to clearly illustrate the process. (He changed his mind after the discovery in the 1860s of some “missing link” species, including archaeopteryx, the first known feathered dinosaur.) But two lessons from the early 19th century were crucial to Darwin’s thinking: extinction and the long history of Earth. The former explained the stakes in the struggle for survival, while the latter made it possible for natural selection to lead to significant divergences among populations. Darwin thought natural selection required so much time, in fact, that he greatly overestimated the length of geological periods, suggesting that the Cretaceous Period began no earlier than 300 million years ago—more than double the current estimates.

Impossible Monsters follows the development of Darwin’s work and its rapid acceptance by scientists who recognized the need for a materialist explanation of how new species had come to be. But Taylor goes even further, discussing paleontology’s influence on the growth of secularism in the 19th century. His previous book, The Interest, was about the British elite’s resistance to the abolition of slavery, and Impossible Monsters traces a similar path: the gradual downfall of an old guard desperately clinging to untenable beliefs.

When Darwin was a student at Cambridge in the late 1820s, the British scientific establishment was insular, pious, and censorious. Oxbridge degrees were available only to members of the Church of England, and professors who strayed from Anglican orthodoxy could jeopardize their careers. One clergyman viewed extinction and deep time as not only heresies but explicit threats to the monarchy, denouncing geologists—including the theologically careful Buckland—as “a secret society dedicated to the overthrow of the established order.” According to Martin Rudwick, a leading scholar of the history of geology and paleontology, such Bible-based objections were “little more than a storm in an Anglo-American tea-cup.” Scientists on the European continent simply didn’t have much to fear from biblical literalists, while in Britain, publishers of works considered blasphemous could be prosecuted by the Crown.

By the time of Darwin’s death in 1882, secular scientists had won many of their theoretical battles against religious opponents and so faced less legal and social censure. Oxbridge lifted its religious restrictions in 1871, and new, well-funded research universities were founded with explicitly secular mandates. A scientific school started by Darwin’s ally Thomas Huxley—who coined the word agnostic to describe his religious skepticism—eventually gained royal consent, becoming part of Imperial College London. Huxley and his fellow scientists in the evolutionist X Club were a powerful force in the British establishment. All nine X Club members were highly decorated, and two received knighthoods from Queen Victoria.

Atheists and agnostics throughout Britain also made political gains over the same period. Charles Bradlaugh, an atheist activist, viewed paleontology and geology as tools in his fight against the Church of England. He founded the National Secular Society in the mid-1860s, lecturing at its Hall of Science to London tradesmen and artisans. When he was elected to Parliament in 1880, Bradlaugh refused to recite the Oath of Allegiance, which was required to take a parliamentary seat—because it included the phrase “So help me God.” The speaker of the House of Commons prevented him from joining the legislature until 1886; in the meantime, Bradlaugh had won four by-elections.

In How the New World Became Old, Caroline Winterer, a historian of science at Stanford University, offers a less triumphant account of science’s relation to religious authority. She writes that in the United States, the distant past was not an argument in favor of secularism but “a new way to talk about God.” In 1851, Edward Hitchcock, a prominent American geologist who taught at Amherst, wrote that Earth’s millions of years of history could give people “more exalted conceptions of the divine plans and benevolence than could possibly be obtained within the narrow limits of six thousand years.” Two decades later, Princeton geologists made the same argument when biblical literalists tried to resurrect James Ussher’s date of Creation of 4004 BC.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Winterer discusses the important discoveries in the 1860s and ’70s of new dinosaur species in the marl pits of southern New Jersey and on the Midwestern prairies. But her book isn’t primarily about dinosaurs. She ranges widely in the scientific literature of the 19th and early 20th centuries, addressing various ways that deep time was used to strengthen claims to American exceptionalism. A vast array of extinct species was drafted into these patriotic campaigns, including trilobites, megafauna (giant mammals that arose after the demise of the dinosaurs), ancient horses, and early humans. Scientists argued that the new nation’s fossil deposits were richer than Europe’s and its geological formations more ancient. The presence of rich coal deposits was seen as a sign that the country’s economic might had been foreordained hundreds of millions of years ago in the Carboniferous Period.

Whereas Taylor shows that the discovery of deep time led Britons to question existing hierarchies, Winterer reveals that the concept was also used to justify racial discrimination and economic inequality in America and elsewhere. Well before the spread of evolutionary theory, deep time established a hierarchy of life, with the older species presumed to be more primitive than newer ones. Because some plant fossils found in temperate climates resemble modern-day tropical vegetation, geologists reasoned that a hotter climate always features simpler life-forms. The relationship between the tropics and primitiveness was extended to human civilization. Climate was destiny, explained the Swiss émigré geologist Arnold Guyot, who taught at Princeton: “The people of the temperate continents will always be the men of intelligence, of activity…; the people of the tropical continents will always be the hands, the workmen, the sons of toil.”

During the Civil War, Southerners used deterministic arguments about climate and race to justify slavery. In 1861, Mississippi announced its secession from the Union by citing “an imperious law of nature,” according to which “none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun” to pick the cotton on which the state’s economy depended. Naturalists in the North, meanwhile, claimed that the South was hopelessly backward on account of its hot climate and geological history. Some thought that because the nutrient-rich glaciers of the Ice Age hadn’t reached below the Mason-Dixon Line, the quality of Southern soil was relatively poor. One Maine glaciologist argued that only “glacial soil” could support “the greatest population, the greatest men, the best system of learning, the most intuitive intelligence, the most wealth, the most commercial activity, the most profitable railroads, and the purest religion.” Winterer views the rise in the popularity of paleontology after the Civil War as part of an “ideological program of enclosing a very brief US national history into a much more ancient history,” stretching back long before the Ice Age, that could bring together American citizens from every region—and that excluded Natives, whose “apparent inability to conceptualize deep time” was seen as “one measure of their primitive condition.”

Other aspects of paleontology offered support for race scientists in the 19th and 20th centuries. In the 1830s, Samuel George Morton, a Philadelphia physician who applied the methods of comparative anatomy to human skulls, claimed that Caucasians had the largest brain cavities and hence were inherently the most intelligent race. Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the American Museum of Natural History from 1908 until 1935, promoted the idea that the races had evolved separately from one another. He argued that only whites had descended from the Cro-Magnon people of southern France, whom he viewed as superior to all other prehistoric humans and to contemporary Indigenous peoples. Osborn wrote the preface to Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race (1916), a notorious work of scientific racism that was praised by the Nazis.

Dinosaurs at the Dinner Party and Impossible Monsters are ultimately concerned with how we got to our current understanding of the history of Earth. Winterer, by contrast, rarely says whether a particular theory has been proved or disproved, and she shows little interest in what geologists and paleontologists now believe. A skepticism of scientific authority is embedded in her historiography, and it’s unclear just how far the relativism goes: How the New World Became Old would have benefited from a firmer statement of her beliefs about the nature of scientific truth—and more specifically about what her readers should make of the racist and imperial associations of geology and paleontology. Winterer never argues that the taint of racial prejudice extends to every aspect of these sciences, yet she obviously encourages us to view claims to scientific authority circumspectly, especially when they bear on social issues.

How the New World Became Old ends with a chapter on the development of Young Earth creationism in the late 20th century. “The Young Earthers have created a land of enchantment teeming with dinosaurs and Bible stories,” Winterer writes, with “mighty brontosauruses and stegosauruses…escorted onto the ark by Noah as parrots and pterodactyls swoop overhead.” The sheer wonder that dinosaurs inspire has been too strong for fundamentalists to ignore, even if everything we know about deep time ought to make a mockery of creationism. Scientific findings have no inherent moral value, Winterer seems to argue; they’re neither good nor bad. They don’t necessarily lead to enlightened policies, and they can be fashioned as rhetorical weapons for practically any ideology—including those opposed to the basic aspects of scientific inquiry. For all the tremendous ingenuity and work involved in identifying ancient reptiles and placing them in the distant past, it has also proved tremendously easy to deploy them in the service of boneheaded arguments.

Time is running out to have your gift matched

In this time of unrelenting, often unprecedented cruelty and lawlessness, I’m grateful for Nation readers like you.

So many of you have taken to the streets, organized in your neighborhood and with your union, and showed up at the ballot box to vote for progressive candidates. You’re proving that it is possible—to paraphrase the legendary Patti Smith—to redeem the work of the fools running our government.

And as we head into 2026, I promise that The Nation will fight like never before for justice, humanity, and dignity in these United States.

At a time when most news organizations are either cutting budgets or cozying up to Trump by bringing in right-wing propagandists, The Nation’s writers, editors, copy editors, fact-checkers, and illustrators confront head-on the administration’s deadly abuses of power, blatant corruption, and deconstruction of both government and civil society.

We couldn’t do this crucial work without you.

Through the end of the year, a generous donor is matching all donations to The Nation’s independent journalism up to $75,000. But the end of the year is now only days away.

Time is running out to have your gift doubled. Don’t wait—donate now to ensure that our newsroom has the full $150,000 to start the new year.

Another world really is possible. Together, we can and will win it!

Love and Solidarity,

John Nichols

Executive Editor, The Nation

More from The Nation

Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments

Dev Hynes moves between grief and joy in Essex Honey, his most personal album yet.

Why “The Voice of Hind Rajab” Will Break Your Heart Why “The Voice of Hind Rajab” Will Break Your Heart

A film dramatizing a rescue crew’s attempts to save the 5-year-old Gazan girl might be one of the most affecting movies of the year.

How Laura Poitras Finds the Truth How Laura Poitras Finds the Truth

The director has a knack for getting people to tell her things they've never told anyone else—including her latest subject, Seymour Hersh.

Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks

The late actor and director leaves behind a roster of classic films—and a much safer and juster California.