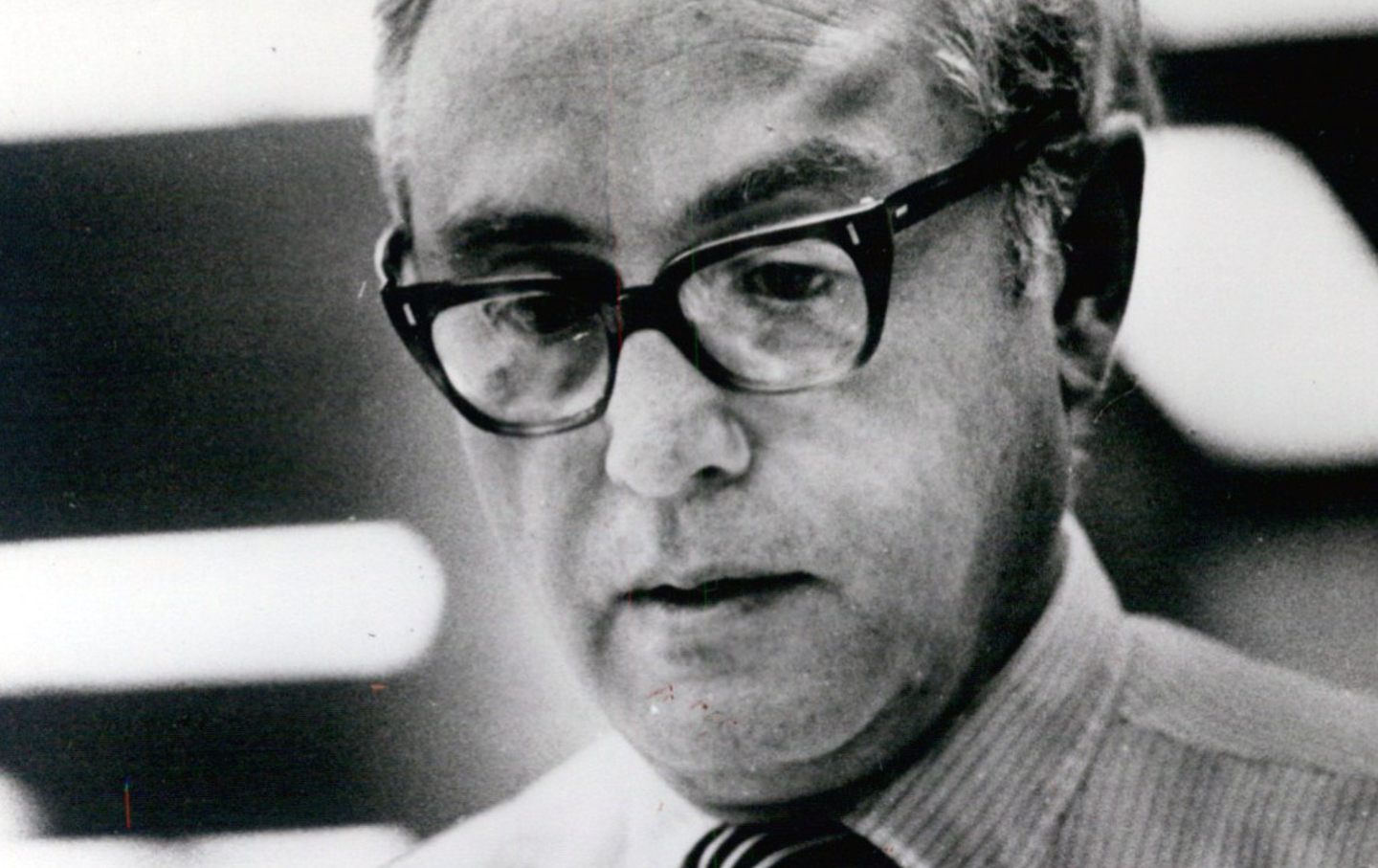

Ralph Nader Remembers Morton Mintz (1922–2025)

A probing, formidable reporter, Mintz broke major stories on corporate crime and fraud in the consumer, environmental, and workplace arenas.

The journalistic career of Washington Post reporter Morton Mintz spanned the years 1958 to 1988 and reveals how starkly different his superior standards and focus on corporate wrongdoing were from today’s Internet-afflicted media environment.

This quiet, persistent, probing, formidable reporter was guided by his repeated question: “What’s important?” This simple yardstick led him to break open major areas of corporate crime, violence, and fraud—in the consumer, environment, and workplace—that many reporters then began to pursue.

Morton chose to be a “beat reporter,” not a feature writer of the sort that has steered so many of our major newspapers toward magazine-type formats that sacrifice hard news.

Being a “beat reporter” meant that he coveted oversight and investigative deficiencies when it came to the Congress, regulatory agencies, and the courts. To achieve this laborious objective, Mintz dug into transcripts of congressional hearings, court records, and the regulatory agency proceedings. He conducted interviews to get deep into the facts.

Mintz’s work ethic also led him to cover activism and lobbying by citizen groups and heroic, unknown whistleblowers. Unlike the media’s censorious exclusion of what citizen groups are doing today, he saw this foundational community turning knowledge into action, into safety and health legislation and into court and regulatory victories for the common folk. His many exposés of the drug, medical device, automobile, asbestos, and tobacco industries, and more, did not satisfy him. He knew the importance of subsequent follow-up reporting on his previous stories, to not only enlighten readers but also to save their lives, protect their safety, and prevent rip-offs by corporations peddling useless, harmful drugs, and other products.

A Morton Mintz story was not going away, and motivated lawmakers knew that he would keep following up. It led them to launch inquiries and hearings, and to listen to the citizen advocates whose legislative proposals often became law.

Mintz kept listening, as well. At lunch with Morton when he was 95, I recall his utter astonishment at being informed that most Washington Post reporters, like others in the mass media, do not return telephone calls or respond to e-mails to receive scoops, leads, and reactions the way he invariably did.

Mintz maintained wide-ranging involvement with his sources, members of Congress, regulators, and advocates in order to fortify his professional standards of independence and probity. He quietly but firmly resisted quaking editors and ignored pressures from corporate lawyers, such as Lloyd Cutler, who represented corporate interests and advertisers.

Mintz paid close attention to young reporters and interns. Sari Horwitz, a multiple Pulitzer Prize winner at the Post, recalled that on her first day as an intern in 1984, where her desk next to Mintz’s, he gave her a binder full of suggested stories, urging her to follow up on any that stirred her curiosity.

Curiosity, a passion for justice, and concern for the underdog made Mintz ask questions that escaped his more jaded colleagues. It led him to become active in his union at the Post and, after his retirement, to raise the status and significance of his professional colleagues. For Mintz it was always about the bigger picture, which meant authoring or co-authoring, with plaintiff antitrust lawyer, Jerry S. Cohen, major books such as America, Inc.: Who Owns and Operates the United States (1971) and Power, Inc., a detailed, 800-page paperback on the Public and Private rulers and How To Make Them Accountable (1976).

Despite his impeccable fairness and accuracy (he always invited responses from his corporate targets), the top brass at the Post, beset by corporate complaints, were not happy with him. They took him off his beat and assigned him to cover the Supreme Court. That was “official source journalism,” which he disliked. He escaped that dittohead role after two years, returning to his chosen subjects, exposing the entrenched, powerful, and their dangerous products.

But it was never the same Post or Washington, for that matter. The Reagan regime’s years, the rise of corporate PAC influence over the Democratic Party, and the growing influence of profit-demanding Wall Street stock analysts after the Post became a listed company weakened the journalistic fabric of the paper. Pushback from his editors intensified, and Mintz left the Post in 1988.

I always thought Mort retired earlier than he desired to at age 66. Nonetheless, he had other fields to plow.

In 1990, he became the chair of the Fund for Investigative Journalism and was a founder of the media monitor Nieman Watchdog.com that was affiliated with Harvard’s Nieman Foundation for Journalism. (He was a Nieman Fellow in 1964.)

In 1993, he exposed the American Civil Liberties Union for confidentially receiving funds from the tobacco industry at the same time that it was defending this cancer-industry’s constitutional right to advertise. The ACLU believed then, as it does now, that corporations have equal personhood with real humans.

As a citizen-activist post-retirement, Mintz wrote an article in 1996 in the Washington Monthly posing 27 important questions for the presidential and other candidates to be asked during their campaigns. He long was troubled by the repetitive namby-pamby questions reporters put to government officials and corporate executives. Some of his former colleagues ignored his advice.

Not to be deterred, Mintz would send probing questions about corporate personhood and immunities for senators to ask Supreme Court nominees at their confirmation hearings. They ignored him as well. I once said, “Mort, welcome to the excluded civic community.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Sacred cows were not off limits to his insatiable curiosity to get the important story. He circulated among publishers an outline for a book on the AARP, to reveal its commercial pursuits and ties with insurance companies that compromised the organization. He was taking tough stands to protect millions of elderly consumer members. But he got no takers.

The setbacks Mintz experienced did not take away from his remarkable career, which spanned so many fronts, and gave concrete meaning to the aphorism “Information is the currency of democracy.” I only recently discovered that this many-faceted graduate from the University of Michigan—where he was an editor of the student newspaper—went into the wartime US Navy, where he commanded one of the troop transport ships during the D-Day invasion of Normandy.

There needs to be a major Morton Mintz journalism award given each year at a streamed public event where old and young attendees can gather to absorb the energy, depth, ethics, and generosity of this exemplar of the fourth estate—which is now in such deep crisis. I hope his family and friends can make this very achievable extension of his many-splendored legacy for future generations an expeditious reality. It will serve as a reminder of his journalistic accomplishments. And of the many ways in which, for our broad civic movement, Morton Mintz was the tough gold standard. He was first and best, again and again.

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?

More from The Nation

Celebrate Kristi Noem’s Firing. But Keep Protesting ICE. Celebrate Kristi Noem’s Firing. But Keep Protesting ICE.

Finally, someone in the administration is paying for their cruelty and incompetence.

We Don’t Need an Autopsy to Tell Us the Democrats Failed on Gaza We Don’t Need an Autopsy to Tell Us the Democrats Failed on Gaza

The DNC is allegedly hiding a report showing that Kamala Harris’s Gaza policy helped cost her the 2024 election. But that report won’t tell us anything we don’t already know.

Texas’s Senate Primary Has Already Made History—and It’s Not Over Yet Texas’s Senate Primary Has Already Made History—and It’s Not Over Yet

Democratic nominee James Talarico is getting national media attention, but the real story is sky-high voter turnout, even amid GOP bids to suppress balloting

Quilted Messages Quilted Messages

Sunbonnets carrying not-so-sunny truths.

How the Theatrics of Mamdani’s Trump Meeting Backfired How the Theatrics of Mamdani’s Trump Meeting Backfired

By pandering to the president’s vanity, the New York mayor reinforced Trump’s image as a strongman commanding deference—an especially bad look on the eve of Trump’s war with Iran

Students in New York Are Going Hungry. How Can Mamdani Help? Students in New York Are Going Hungry. How Can Mamdani Help?

With plans for city-owned grocery stores and a focus on affordability, the new mayoral administration offers fresh hopes of successfully confronting the food crisis among students...