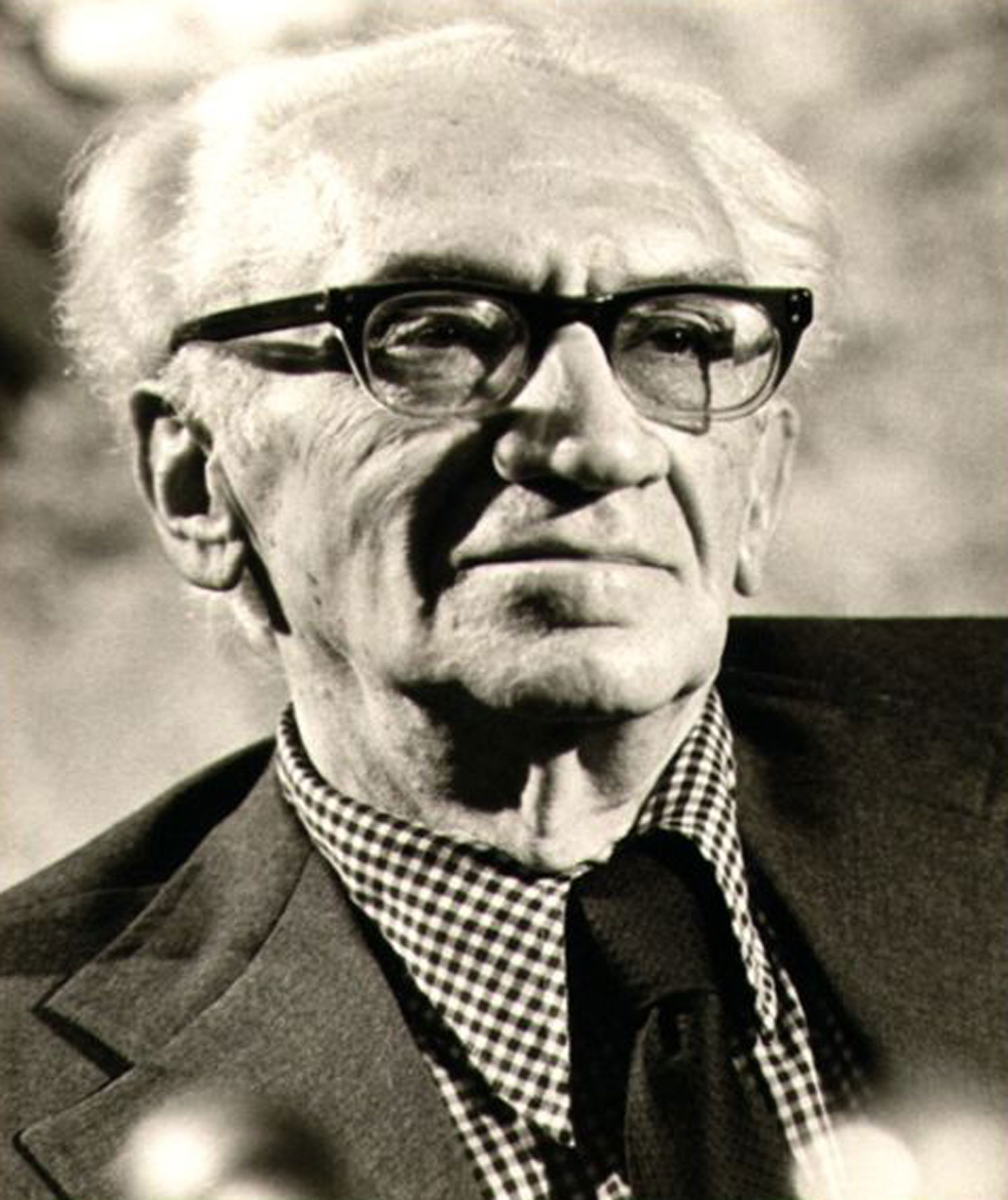

Kurt Vonnegut was the celebrated author of novels like Cat’s Cradle, Mother Night and Slaughterhouse-Five. This article was adapted from a speech he made in Indianapolis to the Indiana Civil Liberties Union (now the American Civil Liberties Union of Indiana) on September 16, 2000. It appears in the collection If This Isn’t Nice, What Is? Advice to the Young, edited by Dan Wakefield, to be published by Seven Stories Press on April 8.

There is something you are entitled to know about me—something I’m not proud to confess. This is it: I was born into a society as segregated as Biloxi, Mississippi, except for the drinking fountains and the buses. And I am the product of a lily-white public high school in Indianapolis. Shortridge had a faculty worthy of a university. Our teachers there, again lily-white, weren’t just teachers. They were their subjects. Our chemistry teachers were first and foremost chemists. Our physics teachers were first and foremost physicists. Our teacher of ancient history, Minnie Lloyd, should have been wearing medals for all she did at the Battle of Thermopylae. Our English teachers were very commonly serious writers. One of mine, the late Marguerite Young, went on to write the definitive biography of Indiana’s own Eugene Victor Debs, the middle-class labor leader and socialist candidate for president of the United States, who died in 1926, when I was 4. Millions voted for Debs when he ran for president.

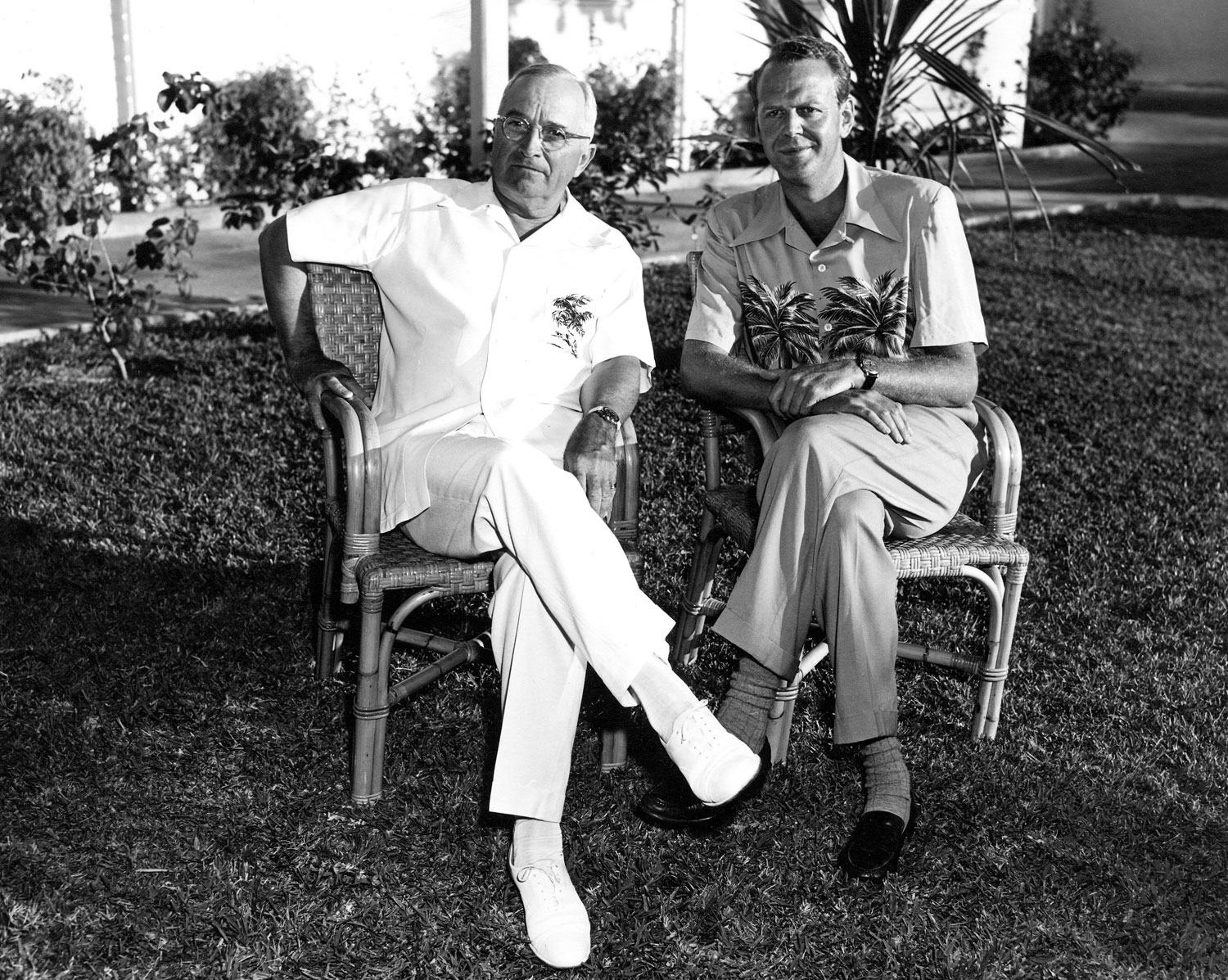

I never met Debs, but I was old enough after World War II to have lunch in this city with another middle-class Indiana labor leader. He was Powers Hapgood. Although he was a Harvard graduate and from a well-to-do family of businesspeople, Powers Hapgood worked as a coal miner to get close, both spiritually and physically, to those he wished to help to help themselves. He then became an officer in the CIO here in Indianapolis.

Not long after our lunch, there was some kind of dust-up on a picket line, and he landed in court as a witness. The judge—Judge Claycomb, in fact the father of my Shortridge classmate Moon Claycomb—knew of Hapgood’s history, and interrupted the proceedings to ask why such a privileged person would spend his life as he had. And Powers Hapgood replied: “Why, the Sermon on the Mount, sir.” And if I am asked why anybody should support their local and national Civil Liberties Unions, I will say that it takes a powerful private organization to compel those who govern us to not violate the crystal-clear laws in the Bill of Rights, just as we would not want them to drive when drunk or park by a fireplug. Given the humane and fair and merciful intent of the Bill of Rights, what I would actually be saying, though subliminally, is: “The Sermon on the Mount, sir or madam.”

If you don’t know what the Sermon on the Mount is, ask your kid’s computer. If you don’t know what the laws in the Bill of Rights are, look ‘em up, look ‘em up. And yes, I know about the Second Amendment, and I’m for it. It doesn’t say people who disagree with a president should shoot him, which is what John Wilkes Booth and Lee Harvey Oswald did. It says in effect that civilians interested in playing with man-killing devices and live ammunition can best serve the rest of us in the National Guard, as long as they don’t shoot unarmed college students. Four unarmed students at Kent State University were shot and killed by Ohio National Guardsmen on May 4, 1970, while protesting against the invasion of Cambodia.

To come back to my lily-white high school: it had such a stunning faculty because the Great Depression was going on, so teaching was a plum job for some of the smartest men in town. But even before the stock market crash of 1929, when I was 7, it had great teachers because teaching high school was virtually the only way brilliant and informed women could make effective use of their warmth and intellectual enthusiasm and giftedness. Most of my best teachers were women and, holy smokes, were they ever bright. So why were women barred then from so many jobs they now hold with distinction? Because of what was then believed to be a law of nature, a natural law.

Why were there no African-Americans in my high school? African-Americans had their own high school, of course. It was called Crispus Attucks. And because of the peculiar name of our black high school, people of all colors in Indianapolis were unusual Americans for knowing who Crispus Attucks was. He was an African-American freeman, not a slave, who stopped a British bullet at the Boston Massacre in 1770, only six years before our nation became a beacon of liberty for the whole wide world. In one book of mine, I nicknamed Crispus Attucks High School “Innocent Bystander High.”

Again: Why were there no African-Americans in Shortridge High School? Because of what was then believed to be a law of nature, a natural law. Nature had obviously color-coded people for a reason. Otherwise, what the hell were all these different colors for? And why was Thomas Jefferson, possibly the most beloved of our founding fathers after George Washington, able to write “all men are created equal,” while meaning only white males—not women, God knows—and while owning slaves? Because of what was then believed to be a law of nature. Jefferson’s slaves were mortgaged, by the way. What a shame that you can no longer take the cleaning lady, along with the saxophone, down to the hock shop if you’re short on cash. Those were sure the good old days.

In quite a few ways, though, it was still the good old days for white males when I was growing up. I could still feel superior, even in the view of law enforcement agencies, to half my own race and 100 percent of all the others. That was comforting! Not only that, but I could get away with all kinds of crap because I was from a good family. But that’s another story.

In our all-white sandlot football games—“Jeffersonian games,” you might call them—the ad hoc captain of the side preparing to kick off would call out, “Are you ready, Crispus Attucks?” And the captain of the receivers would inevitably reply, “We are ready, Ladywood.” Ladywood was the name of a Catholic girls’ school in Indianapolis. Come to think of it, that “Ladywood” business had an anti-Catholic ring to it. Come to think of it, we were not only male and white, but also Protestant. So that “Ladywood” insult was a kind of twofer.

If I have offended some of you by speaking ill of Thomas Jefferson, tough titty for you. I can say anything I please, short of shouting “Fire!” if there is no fire, because I am a citizen of the United States of America. Your government does not exist, and should not exist, in order to keep you or anybody else—no matter what color, no matter what race, no matter what religion—from getting your damn fool feelings hurt. If you found an official powerful enough and dumb enough to actually shut me up about Thomas Jefferson, the two of you would be hauled into court, and the Indiana Civil Liberties Union would make you both feel like something the cat drug in.

Which brings us to St. Thomas Aquinas, a great Italian theologian and philosopher who 700 years ago perceived a hierarchy of laws that human beings should obey. At the top were God’s laws, from the Old and New Testaments, of course. Below them were natural laws, the ways nature—obviously, to both St. Thomas and Jefferson—expected things to go. Lowest of all were man’s laws. If you think of laws arranged in that order in a deck of cards, God’s laws would be the aces, nature’s law would be the kings, and ACLU lawyers, attempting to secure the civil rights of the deuces and treys and even unpopular tens and jacks in our society, would have nothing but pipsqueak queens to play. I once heard a man dismiss the Bill of Rights as “nothing but a bunch of amendments.” Chicken feed, when compared with God and nature.

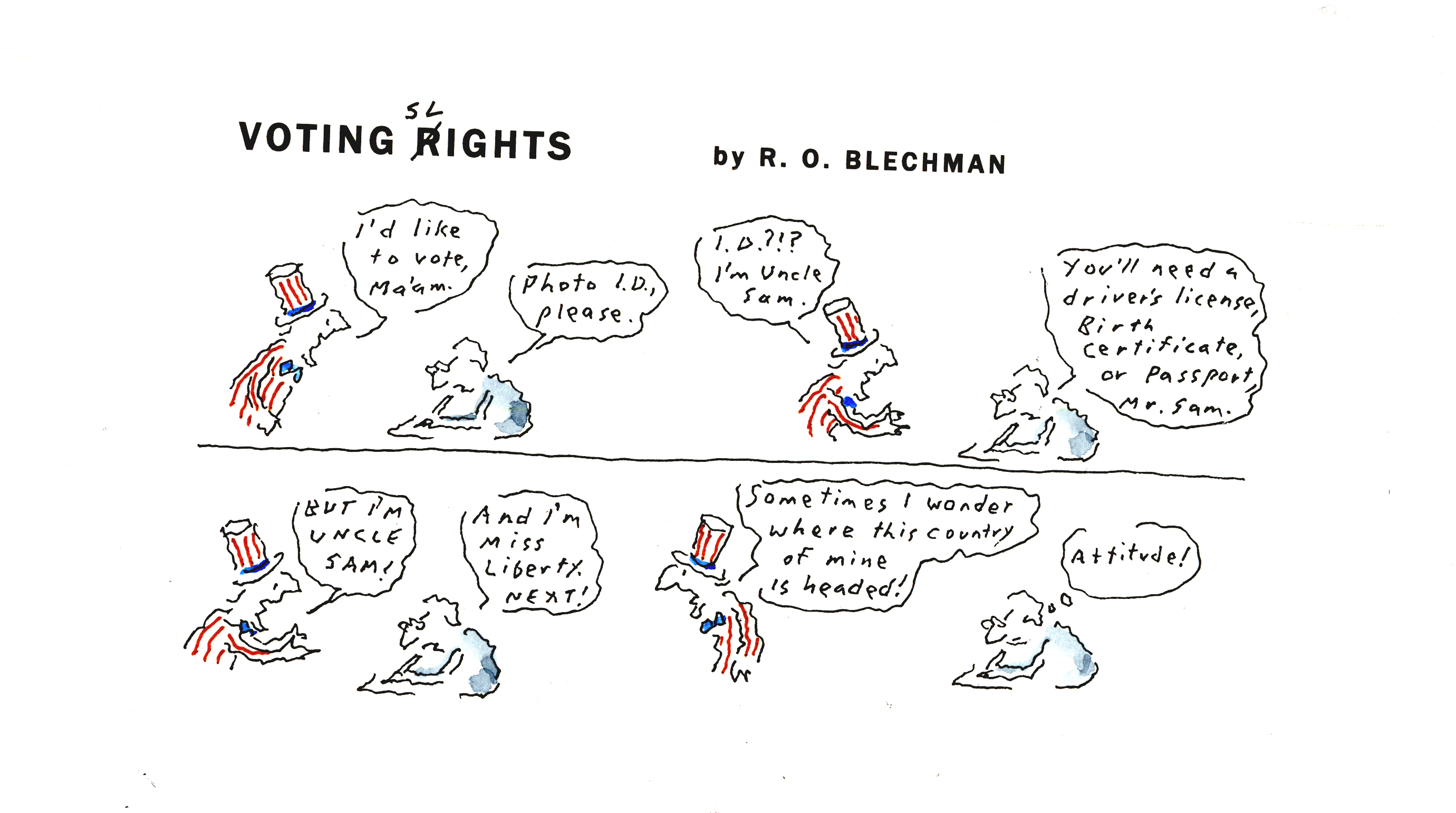

And indeed, the unambiguous laws in the Bill of Rights might as well have been chicken feed, or even chicken droppings, so cruelly spotty was their enforcement until the start of the lifetimes of people my age—people born in 1922. Only two years before we were born were female citizens allowed to vote and run for office. My Lord! And for many years after that—until long after the end of World War II, for heaven’s sake—African-American citizens of both sexes were in many parts of the country, this beacon of liberty, discouraged from voting by a combination of technicalities and sheer terror. Don’t forget: nobody had ever been punished for lynching one. “Nature, red in tooth and claw.”

Who were and are the bleeding hearts who fought, and fight, to make our governments—local, state and federal—behave justly and mercifully and respectfully toward all its citizens, no matter how socially and politically powerless and unpopular they may be? I have an old and once-despised name for them, which may surprise you: they are abolitionists. We are abolitionists. Abolition of what? Of human slavery. Such passions for human rights as we have derive their strength from inherited guilt about the unspeakably hideous crime on which so much of the early and even present wealth of the whole of this “one nation, under God,” is based—the labor of kidnapped persons, of slaves.

Please support our journalism. Get a digital subscription for just $9.50!

And “Nature, red in tooth and claw” is a quote from Tennyson’s poem “In Memoriam A.H.H.,” and refers to predatory animals baring their teeth and claws, stained with the blood of the prey they killed. We tonight are also atoning as best we can for the murder of brothers by brothers, so to speak, in our Civil War. “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord: / He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.”

What did “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and all that have to do with our present enthusiasm for women’s rights? Not that much, really. Women just got lucky this time.

Read Next: “The Worst Addiction of Them All,” an excerpt from the e-book Vonnegut by the Dozen: Twelve Pieces by Kurt Vonnegut Read More

Kurt Vonnegut