Ablikim Yusuf never imagined he would see America. Born in Hotan, an oasis town in arid Xinjiang province, he spent most of his life in China. In 2013 he moved to Pakistan for work, where, until recently, he expected to remain.

But on the second Sunday in August 2019, after a whiplash series of life-altering events, Yusuf, a member of China’s Uighur ethnic minority, stood before some 300 Uighur Americans in Fairfax, Virginia, in a makeshift mosque. It was Eid al-Adha, a day of celebration for Muslims.

Yusuf, who is 54 and slender, wore a blue-striped dress shirt. Speaking in Uighur, he thanked the group for welcoming him and supporting his recent arrival in the United States. He pledged to make good on their kindness. “I will do my best to help my people,” he said.

It had been years since Yusuf was surrounded by so many Uighurs in celebration. Religious customs and ceremonies are largely banned in Xinjiang, which in recent years has become the site of a sprawling humanitarian crisis at the hands of the Chinese government. Human rights groups estimate that more than 1 million Uighurs and other minorities have been arbitrarily interned in facilities that the Chinese Communist Party terms “vocational training centers” but, in reality, more resemble concentration camps, with torture, sexual assault, and death all documented as taking place inside. Outside the centers, Xinjiang’s citizens are subject to extensive surveillance, under which all aspects of Uighur and Muslim life—growing a beard, attending services at a mosque—might be cause for arrest.

Yet in Fairfax, Yusuf found dancing and Uighur fashion on prominent display. Homemade dishes—cucumber salads, crispy spring rolls, skewers of seasoned chicken and lamb—were doled out generously from foil containers. And all around, families sat chatting, gossiping, laughing. It was fascinating, he said, like something from the past.

Just a week earlier, Yusuf had been stuck in Qatar’s Hamad International Airport, facing deportation to Beijing. Uighurs who have traveled abroad are a special target for the Chinese authorities; for a moment, he seemed all but certain to become one more victim of the camps.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Instead, a rapid campaign by activists, much of it waged online, stalled his deportation and ultimately won him refuge in the United States. So, improbably, there he was in Virginia, some 7,000 miles from the life he had known.

That Sunday, well-wishers surrounded Yusuf to offer support and words of encouragement. “We Uighurs stand with our brothers and sisters,” one man told him. “We don’t have much, but we support you with our whole hearts.”

Eid al-Adha is a holiday of sacrifice, and it’s traditional in some Muslim cultures to slaughter a cow, goat, or sheep. Members of one family invited Yusuf to join them at a halal slaughterhouse in Maryland that many Muslims around Washington, DC, use for special occasions. He helped the family clean a sheep that they had procured from Uighur farmers nearby. Together, they bound the sheep’s legs with rope and laid it gently on its side. Covering its eyes with cloth so it wouldn’t see the blade, they read an Islamic blessing, and in one firm swipe to ensure the sheep did not suffer, they slit its throat. It was a memorable day and a very happy one, Yusuf said. It reminded him of home.

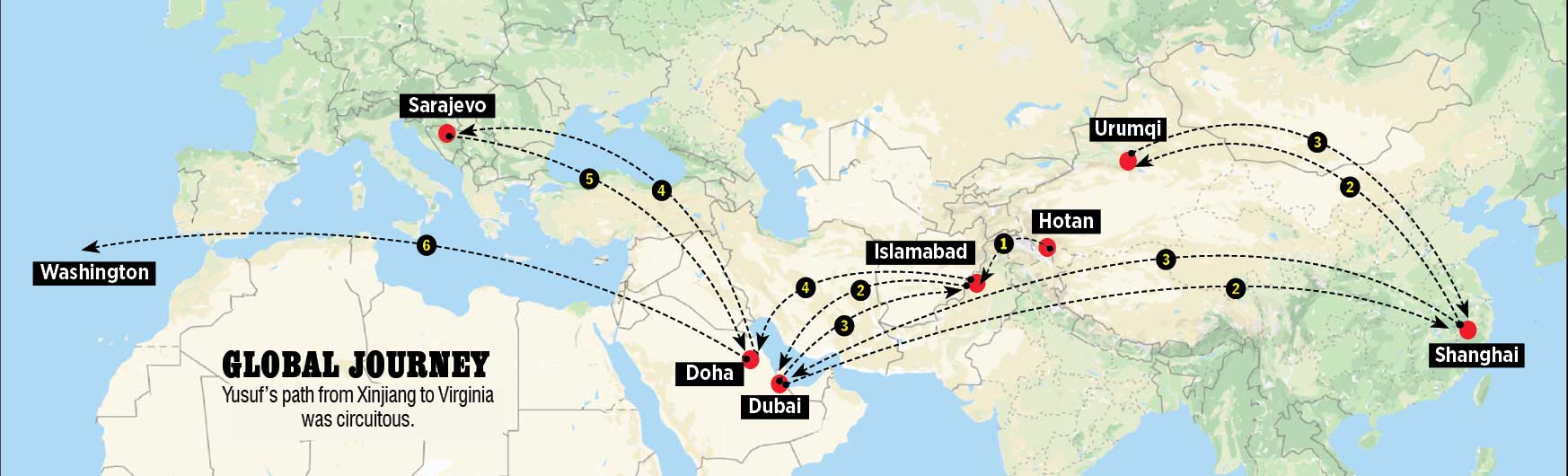

Throughout his life, Yusuf had been aware of the often poor treatment of Uighurs in China, he said, but he thought that if he obeyed the law, it would surely never affect him. After graduating from Xinjiang Radio and Television University in 1984 with a degree in Chinese language, he found employment with a state-run transportation company in Hotan. He later worked for the government directly, then set out on his own in 2007. In 2013 he married a Pakistani woman named Lubna, whom he met through a colleague. Yusuf moved to Islamabad in the years leading up to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a multibillion-dollar infrastructure project to boost trade between the two nations and a (now faltering) centerpiece of China’s continent-spanning Belt and Road Initiative. He owned an import-export company and managed shipments of fruits, nuts, juices, and machinery between Pakistan and China. Business was good, and he soon earned an official Belt and Road contract. The couple moved to Islamabad’s upscale Bani Gala neighborhood, not far from Prime Minister Imran Khan’s residence. In 2014 they welcomed a son, whom they named Ibrahim.

In April 2017, Yusuf flew to Shanghai on business. Unbeknownst to him—and, at the time, to much of the world—China’s anti-Uighur campaign in Xinjiang was underway. Thus, when customs officials in Shanghai stopped him in the airport, seemingly for no other reason than that he was Uighur, Yusuf was shocked. He said the officials contacted authorities in Xinjiang, who directed that he be sent to Urumqi, Xinjiang’s capital. A five-and-a-half-hour flight later, he arrived in Xinjiang.

Yusuf recalled being greeted in Urumqi by men who he believes were guobao—Chinese state security, ubiquitous in Xinjiang. The men, in plain clothes, loaded him into an unmarked car and drove to a hilltop facility on the outskirts of town, he said. There, under an array of bright lights and video cameras, he was interrogated for four days.

The men demanded to know what he was doing in Pakistan. Who had he met there? What did he do with the money he was making? And crucially, what did he think about China? Yusuf insisted he was just an ordinary businessman. He bore China no ill will, he said; moreover, his detention could threaten an open Belt and Road contract. It was that last point, he said—and perhaps the quality of his Chinese—that ultimately persuaded his captors to relent; he was allowed to go home to Pakistan, albeit with a written order to return to Xinjiang in a month.

Back in Islamabad, Yusuf was furious. “I totally lost trust in the country,” he said of China. Certain he would meet the same fate or worse if he returned home, he stayed in Pakistan. After about a month, he received word from his sister in Hotan: The police were in their family home, asking about him and making threats. Days later, his brother went missing.

Dismayed, Yusuf did everything he could to help locate his brother. He reached out to his brother’s friends, but the lines were dead. An answer finally came from a colleague in Urumqi over WeChat. His brother was in the classroom—a euphemism for having been sent to the camps. Xuexi ban: He is studying.

In time, even Pakistan came to feel unsafe for Yusuf. In July 2018 he attended a party with a business associate. There he was introduced to a group of men who, upon learning he was originally from Xinjiang, told the others present that they recently helped deport nine Uighurs to China. The men spoke in Urdu, he said, apparently thinking he couldn’t understand, but he did. He recalled that they said it was easy to send the Uighurs back and that they were paid handsomely to do it. (The Pakistani Embassy in Washington did not respond to a request for comment regarding the country’s treatment of Uighurs.)

About a month later, when he applied for a visa to stay on in Pakistan, the Interior Ministry turned him down. “You guys are supposed to go back to your homeland,” Yusuf said he was told. Then his bank account was frozen, and he was no longer able to run his business.

According to Patrick Poon, a China researcher at Amnesty International, Pakistan is one of several countries (including Muslim ones) that not only tolerate the abuses in Xinjiang but also in some cases actively support Beijing’s efforts. “It’s quite obvious some countries are putting their economic development and business interests above human rights,” he said.

In December 2018, a spokesperson for Pakistan’s Foreign Affairs Ministry accused journalists of sensationalizing China’s Xinjiang policy and “spreading false information.” The prime minister, who postures as a defender of Islam on the world stage, has claimed ignorance regarding China’s actions. The following July, Pakistan was among 37 countries to publicly back that policy in a signed letter to the United Nations.

Economic considerations certainly account for this sycophancy, but other countries’ own authoritarian tendencies shouldn’t be ignored here, explained Sophie Richardson, the China director at Human Rights Watch. “I would be willing to believe there are people in [the Pakistani] government who believe that what’s happening in Xinjiang is just the right way to go,” she said.

Yusuf and Lubna weren’t taking any chances. She urged him never to leave the house alone. By the end of 2018, he had stopped leaving the house altogether. “It was a very fearful year,” he recalled darkly. They decided that he needed to escape, even if it meant leaving her and Ibrahim behind.

But there was a problem: Yusuf had lost his passport in late 2017, and the Chinese Embassy in Islamabad wouldn’t replace it. Instead, he received a “travel document” for Uighurs, which looks like a passport but isn’t. The document states that the bearer is entitled to travel between countries, but whether the person is allowed entry is dependent on a country’s willingness to honor the document. For China, such documents function as an implicit means of forcing people to return. Thus began Yusuf’s fraught and incredible journey around the world.

Yusuf’s first attempt to leave Pakistan came in January 2019. He was turned away at the airport in Islamabad, so he went to Karachi instead. There, he was told that he would need an exit permit affirming that he carried no debt and had no criminal record in Pakistan. He decided it was too risky to seek the exit permit in person, so he appealed to his business and social contacts for help, and in late July the permit arrived—a small miracle. Soon after, he took a cab to Islamabad International Airport; a friend of a friend who worked there was on hand to help see him through.

From there, the plan was simple. He flew to Qatar and went on to Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has no visa requirement for Chinese travelers. He planned to then buy a ticket to China—a destination that customs officials would surely permit, given his travel document—with a layover in Germany, likely in Frankfurt. There, finally, he would claim asylum.

But Yusuf never made it past Bosnian border control: Officials declined to recognize his travel document. He was sent back to Doha and booked on a Qatar Airways flight to Beijing.

Before departing, he contacted Lubna for what he thought might be the last time. If she never heard from him again, he begged her to speak out—to stand in front of the Chinese Embassy in Islamabad and “make a noise for him and the Uighur people.” She told him she would, and they bade each other a tearful goodbye. Yusuf wondered if there was anything else he could do.

With nothing to lose, he recorded a video on his phone to share on Facebook. “My name is Ablikim,” he started, with the airport’s glowing shops and bustling passengers filling the frame behind him. “I am currently being held at Doha airport, about to be deported to Beijing, China…. I need the world’s help.”

Against all odds, the post went viral. Across social platforms and around the world, Uighurs and human rights leaders shared his story, using the hashtag SaveAblikimYusuf. And Yusuf, one man in a crisis that has affected millions, became global news.

Tahir Imin, a prominent Uighur activist and academic in DC, was at home working on a paper when an associate in Turkey sent him the clip. Imin added it to a WhatsApp group of journalists and activists. Soon he was connected with Kimberley Motley, an international human rights lawyer who agreed to represent Yusuf. Motley, in a movie theater in North Carolina at the time, immediately e‑mailed the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees to launch a formal asylum petition on his behalf. Meanwhile, Omer Kanat, who directs the Uyghur Human Rights Project in DC, blasted e‑mails to State Department contacts, who likewise launched into action.

Qatar, suddenly under pressure from the UNHCR and the United States—and with protesters outside its embassy in Washington, to boot—agreed to delay Yusuf’s deportation. Officials escorted him to an airport hotel, where he was determined to remain until he was safe. It wasn’t long, however, before more officials came knocking at his door. First there were Qatari police officers. The Chinese ambassador to Qatar wanted to meet him, they said. Motley, who communicated with him through Imin, advised against it, so Yusuf told the men to go away.

In DC the State Department lobbied countries that might accept Yusuf, even temporarily. They all declined. The decision to allow him to come directly to the United States was made quickly, Motley said. Everything seemed on the right track, and activists, including Imin, were beginning to breathe easy.

Then a text arrived from Yusuf that read, “They are sending me back to China. Goodbye.”

In the midst of the diplomatic maneuvering, Yusuf recalled, a woman claiming to represent the Chinese Embassy paid him a visit at the hotel. She was accompanied by a group of men. Stop with this social media campaign, she told him through the door. He refused and told her, too, to leave. (The Chinese Embassy in Qatar denied that it sent a woman to his room or made any demands of his use of social media. Consular officials went to the airport only to offer him assistance and take him refreshments, “our normal practice based on humanitarian considerations,” an embassy representative said.)

A short time later, more men showed up on their own. When Yusuf opened the door—a mistake, he said—they burst into the room and slammed him to the ground. He had two choices: He could get on a plane to China willingly, or they would put him on one.

It’s a dangerous time for Uighurs in the world. Despite international pressure, China’s crackdown—which the government insists is necessary to curb extremism—has only shown signs of expanding. Elsewhere, Uighurs face increasing pressure from governments that are swayed by China’s political and economic clout and oppose any interference in another country’s internal affairs, often because of their own repressive policies. Under the UN Convention Against Torture, to which Qatar is a signatory, no nation is required to deport someone to a country where that person has a reasonable fear of torture or abuse. But in the case of the Uighurs, China’s influence has had a tendency to override the convention.

Motley had told Yusuf that if the authorities in Doha tried to force him onto a plane, he should go kicking and screaming. So he did.

“No China! No China!” he yelled in Urdu, thrashing and writhing as the men continued to strong-arm him. Eventually, they gave up and moved him to a quiet room at the airport.

A voice message came through from Imin, in English, explaining that the US government and international agencies took up Yusuf’s case after hearing about his situation. Before long, his lawyer sent him a text message informing him that he was cleared for takeoff—to the United States. “I thought, ‘Is this my dream?’” he said later. “‘I don’t want to wake up.’” He called Lubna, and now they cried tears of joy.

The next morning, he boarded Qatar Airways Flight 707 to Washington Dulles International Airport. Even in the air, he was anxious. He worried that the plane would turn around suddenly or a Chinese official would appear in the aisle.

But on Tuesday, August 6, around 3 pm, the plane touched down at Dulles. When he saw Imin in the airport, smiling with a State Department official at his side, Yusuf was so happy that he cried out.

If Yusuf’s story is emblematic of China’s increasingly long reach in the world, it also represents a shift in the Uighur American diaspora, which members said has been forever changed by China’s atrocities.

The Uighur community in DC raised about $5,000 to help Yusuf find his feet. In the past, raising this sum for a refugee might have taken weeks, but in his case, it took less than 24 hours, Kanat said—a clear sign of the solidarity that has come to permeate the diaspora amid hardship. “This [crisis] was a turning point,” he said. “Uighurs who were not involved in any kind of activities and had distanced themselves from political activities…all became very active.”

There are more than 8,000 Uighurs living in the United States, according to an October estimate by a Uighur scholar in Colorado, with the greatest concentration in the DC area, especially in Fairfax. The US Uighur population is not the biggest (larger expat groups exist in Turkey and parts of Central Asia), but according to Kanat, it stands out for the role it plays in advocating for Uighurs on the world stage.

When Kanat moved to the United States in the late 1990s—at which point the situation in China was already perilous for Uighurs—it was a challenge for activists to find a friendly ear in DC. “We had a lot of difficulty explaining who the Uighur people are,” he recalled. An Amnesty International report in 1999 documenting the “gross violations of human rights” in Xinjiang provided an opportunity, and the Uighurs found an early ally in California’s Representative Tom Lantos, a Holocaust survivor and frequent champion of human rights.

The Uighur cohort in DC grew (to include Rebiya Kadeer, a nominee for the Nobel Peace Prize upon her release from a Chinese prison in 2005), and activists became more adept at navigating the capital’s officialdom. Some politicians have become reliable advocates—Representative Jim McGovern and Senator Marco Rubio, who lead the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, for example, and Representatives Chris Smith and Brad Sherman, who last year introduced bills to condemn and punish China.

In general, though, human rights groups have criticized the US response as slow and indecisive. “For the first year or two, what we heard was a lot of rhetoric without much consequential policy follow-up,” Richardson of Human Rights Watch said. But recent developments are promising, including the House’s passage of the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act last month and a round of visa restrictions targeting Chinese officials, instituted by Donald Trump’s administration in October.

When it comes to the White House, anything that has been done to help the Uighurs may stem from the Trump administration’s emphasis on “religious freedom” at home and abroad. In September at a luncheon hosted by a Christian nonprofit, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo shared Yusuf’s story and said the State Department’s role “demonstrates the lengths that America goes to defend religious freedom around the world.”

Vice President Mike Pence, frequently critical of China, is also generally regarded as an ally of the Uighurs, even if the administration’s policies aren’t exactly Muslim-friendly. Trump has largely avoided comment on the matter. His first and apparently only public remarks on Xinjiang came at a “religious freedom” event at the Oval Office in July, when a Uighur woman, Jewher Ilham, recounted the story of her father’s detention. “That’s tough stuff,” the president told her, after asking about Xinjiang, “Where is that? Where is that in China?”

After Yusuf landed in Virginia, Imin and others helped him find a place to stay: a room in a house occupied by five other Uighur men on a leafy street in Fairfax. Set in an English basement, the room was small and didn’t get much light, but to Yusuf it felt enormous. “I was free,” he said. “I was free.”

Yusuf said he was surprised by a lot of things about America: It was greener and the people were friendlier than he expected. It was a relief not to feel he always had to watch his back. Mundane details also struck him as remarkable—for example, Fairfax’s tidy lawns, orderly traffic, and the relative lack of people smoking on the street.

Four days a week, Yusuf takes English classes, twice at an Anglican church in Fairfax and twice at another nearby church, where missionaries ejected from Xinjiang serve the Uighur community in Virginia. He said he might start a business one day—a Uighur restaurant, perhaps, or something like the company he ran in Pakistan. In any case, he hopes he can give back to the community.

In October, Motley, who continues to represent Yusuf legally, filed his formal application for asylum. The wait can be notoriously long, but she hopes the media attention on his case and Pompeo’s remarks about it might help expedite the process.

Getting Yusuf’s wife and son to the United States, on the other hand, will likely prove an uphill battle, as bringing them here on his account would require him to have permanent residence or citizenship. But Lubna and Ibrahim might qualify for asylum on their own, Motley said. The two are safe for now but fear that Pakistan’s cooperation with China could soon place them in jeopardy as well.

In the meantime, Yusuf speaks with Lubna every day. When he eats, he props the phone up beside him with the camera on so they can see each other. He knows that the chances of getting her and Ibrahim to the United States are slim—but so were his. So Yusuf has vowed to try. “That would be my dream,” he said. “That would be paradise for me.”