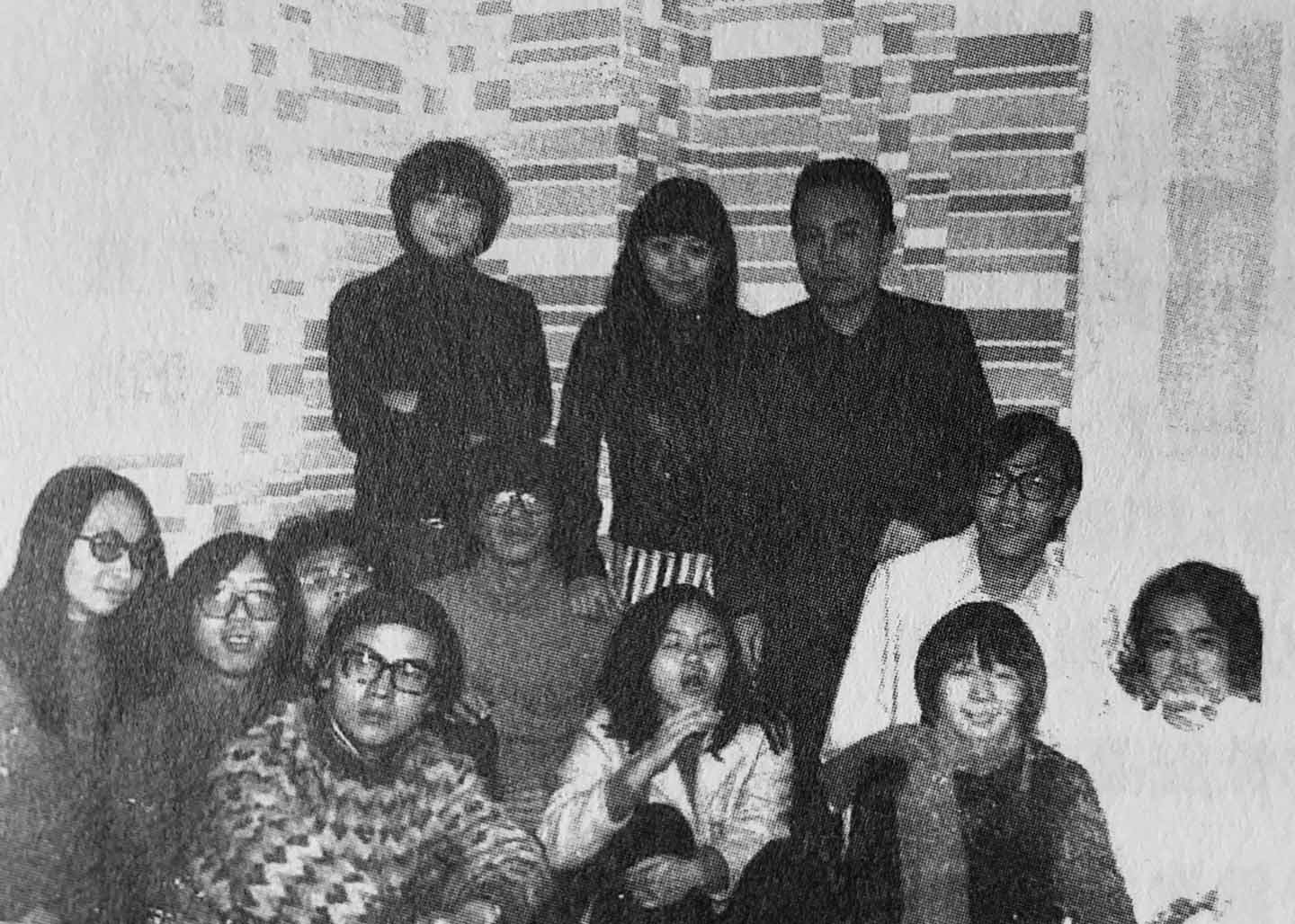

When Ng Chung-yin met Augustine Mok Chiu-yu, they were doing a sit-in protest on the steps of Chu Hai College in Hong Kong. It was August 1969, and 12 students had just been expelled from the college for criticizing the administration—namely, its censorship of student newspapers, corruption, and ties to the Nationalist Party in Taiwan. Ng, then 23, was a former student leader who had just graduated from Chu Hai. Mok, 22, had recently returned to the city after studying in Australia.

“I was a youth [social] worker then,” says Mok now, “basically looking for people with whom I could work to develop a ‘revolutionary’ movement.”

The Chu Hai protests were the first in Hong Kong history in which student unions from schools across the city took to the streets together. The protests ended in failure, and local newspapers smeared the students, claiming they were disrupting public order. Nonetheless, the short-lived movement marked the beginning of a new generation of activism. It had politicized young Hong Kongers, getting them ready for a larger fight.

That’s when Ng and Mok—influenced by their exposure to leftist publications from Australia and the United States—decided to launch a publication that could support a revolutionary upsurge.

On January 1, 1970, the two activists and a group of other like-minded leftists published the first issue of a magazine called The 70’s Biweekly (70年代雙週刊). Filled with political essays, book and film reviews, and reportage—mostly written in Chinese, with some English—and illustrated with photographs, drawings, and collage, The 70’s Biweekly was a profoundly DIY operation. It was only published for a few years. But its radical politics, and the networks of students and workers it helped to form, had an outsized impact that survives to this day. The collective’s members and those inspired by the magazine have helped to define what the Hong Kong left could be.

Last June, a controversial bill that would’ve allowed mainland China to extradite people from Hong Kong triggered perhaps the biggest social movement the city has ever seen. Although there have been few protest actions since the outbreak of Covid-19, the resistance has nonetheless continued for more than ten months—including an upsurge of new unions, formed as an anti-establishment tactic by rank-and-file workers. With the left’s history of activism in Hong Kong, one might expect that it would take a big part in the protest movement. But aside from the interest in unionization, traditional leftist groups have mostly been unable to make their mark.

Looking back at The 70’s Biweekly—both its rise, and its fall—helps us understand why that might be. When the collective was founded, Hong Kong was a British colony, and leftist discourse was dominated by pro-Chinese Communist Party Maoists. But The 70’s Biweekly did not support the CCP. Instead, its ranks were split between Trotskyists and anarchists, committed to a left internationalism that centered on local issues. Members of the collective played an important role in the campaign for Chinese to be adopted as an official language, at a time when the British colonial government only recognized English; they became a central force during other anti-imperial protests, too. Even after the magazine was defunct, its members and readers continued to participate in activism through the 1980s and ’90s, from advocating for Hong Kongers’ right to participate in the handover negotiations, to solidarity actions with dissidents in mainland China.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Hong Kong activists have been waging the battle of their lives for self-determination. Yet structural, economic critiques against the system have been largely delinked from the current movement’s legitimate demands for human rights. Since the days of The 70’s Biweekly, China has joined the United States as one of the world’s most inequitable and exploitative economies, and Hong Kong has become one of the most expensive cities in the world. The China-US trade war has put extra pressure on Hong Kongers, making them feel as if they need to choose between global superpowers. The city’s residents desperately need a radical, working-class-centered movement against globalization and class inequality—especially as the small, localist right, with its US-flag-waving and anti-mainland Chinese sentiments, threatens to grow in influence.

Fifty years after it first hit newsstands, The 70’s Biweekly’s fight against structural oppression and state power—whether it comes from Beijing, Washington, or Hong Kong itself—feels newly relevant.

Hong Kong was a much smaller place before 1949. At the close of the Chinese Civil War, a large influx of working-class refugees and immigrants from the mainland entered the city, more than tripling its population between 1945 and 1951. Hong Kong had been a British colony since the middle of the 19th century, and its ruling class was made up of both British and Hong Kong business elites. But low wages, poor working conditions, racism, and a lack of civil liberties stimulated a new political opposition to British rule—split between the left-leaning Communists and the Nationalists, or Kuomintang.

Maoism quickly became the key political framework for many Hong Kong leftists. And, like many Third World movements emerging around the world, the Hong Kong left’s local struggles were bound up in the larger struggle of anti-colonialism—one that pitted the People’s Republic of China against Western imperialism.

The Cultural Revolution was underway on the mainland, and CCP sympathizers in Hong Kong attempted to extend this struggle into the city. Maoists established a presence in Hong Kong schools and factories, and in 1967, a small labor dispute ballooned—with the CCP’s encouragement—into citywide anti-colonial demonstrations. Much like today, police violence against protesters was rampant. But CCP supporters also planted bombs around the city in an attempt to murder some of the movement’s critics, and ended up hurting uninvolved civilians. By the time the protests ended after six months, more than 50 people had died, and more than 800 had been injured—both by the Hong Kong police and by Communists’ bombs.

By the time Ng and Mok launched The 70’s Biweekly in 1970, the left’s reputation was in tatters, and Hong Kong was still struggling to find its own identity. Nonetheless, Ng, Mok, and the other founders managed to fund the first issue of their magazine with a generous donation from a young monk, one of the 12 students who had been expelled from Chu Hai. Ng was the only paid staff member, while Mok worked as a social worker. The others supported themselves playing music in nightclubs, processing herbs as assistants to Chinese herbal doctors, and selling cheap shoes and slippers in small shops.

From the beginning, The 70’s Biweekly covered a wide range of subjects, including everything from reviews of translations of Bertolt Brecht’s poetry, to a special edition on the struggles of the newly independent country of Bangladesh against what was then called West Pakistan. In that 1971 issue, pseudonymous writers called out the CCP’s complicity in the genocide of Bengalis the year before. “The CCP’s support of West Pakistan is counter-revolutionary!” wrote one, above a kitschy reproduction of Chinese premier Zhou Enlai’s letter to West Pakistani president Yahya Khan. The collective members printed and distributed the publication themselves from the beginning, delivering it to newsstands around the city on foot. (Confusingly, there was also a publication called The Seventies Monthly founded around the same time, but that magazine was then aligned with the CCP.)

Beyond publishing a magazine, members of The 70’s Biweekly helped organize public actions and assemblies. By late 1970, its members had formed an organizing network called the Worker-Student Alliance, drawn from the publication’s readership and divided into local political dialogue and action committees. The collective’s members hoped that these committees would help connect the campaign to make Chinese an official language with other Hong Kong issues. “These platforms saw workers as agents of revolutionary change,” says Mok. (One prominent organizer at the time was Lau Chin-shek, who later helped found and became president of the prominent, pro-democracy labor group the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions.)

Then, in August 1970, the Japanese government reiterated its claim over the Diaoyutai or Senkaku Islands, granting Western oil companies and its own government the right to defend the island chain from foreign encroachment. These uninhabited islands had been governed by the United States since the end of World War II, but their sovereignty has long been disputed by China, Japan, and Taiwan. (The discovery of oil reserves near the islands had made their ownership even more contentious.) The struggle over Diaoyutai reignited nationalistic, anticolonial sentiments among everyone from Chinese and Taiwanese nationalists to American student groups.

The 70’s Biweekly played an integral part in what Hong Kongers called the Baodiao (short for Bao Diaoyutai, or “Protect Diaoyutai”) movement, building on the Chu Hai youth movement of the year before. Members of the collective sympathized with the outrage aimed at Japan and organized one of the first Baodiao rallies to take place in Hong Kong, as well as many others later that year. But instead of supporting the Kuomintang or the CCP, both of which laid claim to the islands, The 70’s Biweekly emphasized how imperialist forces exploited local communities—no matter which nation-state was in charge. Their actions included a rally on July 7, 1971, that marked a turning point in public sentiment: Police violently cracked down on a group congregated at Victoria Park, which included over 3,000 leftists, student organizers, and journalists.

Meanwhile, the collective began corresponding with leftists from mainland China who had been exiled after 1949, such as Chinese Trotskyist Wang Fanxi in Macau. Starting in 1970, members including Ng, Mok, and now-eminent film director John Shum took several trips to Paris, a hub for Chinese Trotskyist exiles such as former CCP member Peng Shuzhi. Some also visited the UK, where they met with staff of the New Left Review and members of the Socialist Workers Party.

And yet, despite its successes, The 70’s Biweekly collective was plagued by internal disagreements between its Trotskyist and anarchist elements. It was also having financial issues; the publication had been supported only by its sales, Mok’s salary as a social worker, and some inconsistent donations from allies. The Baodiao movement was imploding around them, crumbling under the tensions between those who supported the CCP and those who did not.

After July 1973, The 70’s Biweekly stopped regular publication. Some members departed for personal or political reasons; others shifted their activism to other issues. The publication would later start up again for a few issues in 1975, then again in 1978, before being completely discontinued.

The same loose structure that allowed for vibrant debate and participation had also made it difficult for the collective’s members to keep the energy going long-term. However, The 70’s Biweekly’s brief appearance had already woken up many young readers—including some who would play foundational roles in the Hong Kong left.

Au Loong Yu was a teenager when the Baodiao movement kicked off. He has said that those protests changed his life; by the time he met people from the 70’s Biweekly crowd in 1974, he was radicalized. “A majority of the key themes of today’s political debates came up before, in the 1970’s,” said Au, who is still an activist organizing around Chinese labor and local Hong Kong issues, in a recent interview with the Hong Kong magazine The Initium. “The problem of Hong Kongers’ identity, the need for an anti-colonial movement, how to perceive the politics of the PRC, and how to negotiate China-Hong Kong relations.”

The 70’s Biweekly had operated on the idea that colonial exploitation transcended borders, and resistance should be led by the masses—not by paid revolutionaries and union bureaucrats. By the time Au entered the scene, former members of the magazine collective had turned their attention to activism.

One former 70’s editor, Fu Loo-bing, led factory workers in a hunger strike over low wages. He was arrested for causing a public disturbance and held for a few days, then released after more than a thousand people surrounded the police station. Others got involved in a mass campaign against a former Royal Hong Kong Police superintendent who had been accused of corruption. In 1975, Ng, Au, and some former 70’s Biweekly members formed a Trotskyist collective called the Revolutionary Marxist League (RML) and turned toward workers’ organizing.

Then, in 1976, Mao Zedong died. Within two years, Deng Xiaoping was leader of China. As Deng consolidated power, he began to undo many Mao-era job protections, such as the right to strike and guaranteed lifetime employment for workers at state-owned enterprises. China’s economy was thrust into rapid, free-market liberalization, lifting millions of working-class people out of extreme poverty but entrenching them in class antagonism and deeper exploitation.

Solidarity with workers in China soon became a natural avenue for former 70’s Biweekly members, readers, and their respective organizations. In 1980, Au and other organizers formed a grassroots collective called the Pioneer Group; they became one of the earliest organizations to publish leftist writing about China’s capitalist development, and they advocated for Hong Kongers’ right to be involved in handover negotiations. In 1981, Ng and other Hong Kong activists were arrested in Beijing and forced to confess to doing underground organizing work there.

Meanwhile, other individuals associated with The 70’s Biweekly, including John Shum and Leung Yiu-chung, helped build big-tent networks and organizations to support dissidents and workers in mainland China. Leung cofounded an organization that would eventually become the Neighbourhood and Workers’ Service Centre, now a small but influential left-wing political force. The Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China was another such group, albeit one dominated by liberal democrats; it helped launch underground operations after the Tiananmen massacre on June 4, 1989, rescuing mainland dissidents by bringing them to Hong Kong.

Despite these initiatives, leftist ideas weren’t resonating with the public the way they had in the past. Working and living conditions were becoming more precarious; manufacturing jobs sharply declined, while real estate prices skyrocketed. Hong Kong—which had industrialized just a couple decades before—was becoming a global financial hub, just in time for the handover in 1997. As the city transformed, the left struggled to reach an audience.

Leung “Long Hair” Kwok-hung is a long-time activist and former member of Hong Kong’s law-making body, the Legislative Council. His penchant for direct action and Che Guevara shirts have made him a recognizable figure on the anti-authoritarian left.

As a young teenager growing up in a lower-class family, Long Hair read The 70’s Biweekly and participated in some of the actions it organized. He credits the publication and its members with making him abandon his former Maoist ideology, and with framing a commitment to local, grassroots causes that still inspires him to this day. But he’s not sure it would convince many Hong Kongers now. “It was easier to capture people with a left and Marxist analysis then,” says Long Hair. “While you can talk about it now, the language wouldn’t resonate with many.”

Since the 1980s, most leftist movements in Hong Kong have failed to attract mass participation, or imploded soon after appearing. When Au’s Pioneer Group tried to rally Hong Kongers to demand a say during Sino-British handover talks, they were actively shut out by liberal democrats; the latter preferred a more conciliatory approach to negotiating with China, rather than demanding universal suffrage right away. In 2005, thousands of Hong Kongers and international allies protested a World Trade Organization conference held in the city, opposing the policies of neoliberal globalization—but the momentum didn’t extend beyond the conference. In 2013, there was a dockworkers’ strike, supported by many students and workers’ organizations, but internal strife and attacks from the right shattered hopes for a mass movement.

Then, in 2014, the Umbrella Revolution began, in response to electoral reform that increased Beijing’s power in Hong Kong’s election process. Soon, over 200,000 people were participating in protests. But the reform was upheld, and again, momentum dissipated; some key protest leaders were later jailed. Many were still debating Umbrella’s legacy when protests began last summer—especially because of the localist right-wing factions that grew in its aftermath. These groups, while still small, have become more influential in promoting pro–United States views and xenophobic anti-mainland sentiments.

Long Hair’s political party, the League of Social Democrats (LSD), has perhaps been the most visible and effective left-leaning force in the Legislative Council since its inception in the mid-2000s. Long Hair himself lost his seat in 2017, when he and other elected officials were disqualified for protesting the CCP’s authority. But LSD was nonetheless pivotal in organizing against the extradition bill last summer, as protesters rallied around what they call the “Five Demands.”

When pro-democracy candidates swept Hong Kong’s district council elections in November, it was seen as a clear show of support for the protesters. Still, Long Hair and other LSD leaders see less of an opening to politicize people around deeper structural issues such as class exploitation. “The Hong Kong left’s biggest problem isn’t determining whether capitalism has any fatal problems,” says Long Hair, “but how to build an effective socialist movement anew.”

The Hong Kong left is still experimenting. Last August, protesters called for a general strike to pressure the government over the Five Demands; the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions reports that over 350,000 workers from more than 20 sectors participated. This triggered a new, ongoing interest in unionization and political strikes, and dozens of small-scale unions have since been organized by everyone from theater professionals to workers who manufacture medical equipment. Pro-strike messaging channels on the encrypted app Telegram now have tens of thousands of subscribers. The recent outbreak of Covid-19 saw the quick mobilization of thousands of unionized medical workers, demonstrating the growing willingness of rank-and-file workers to use labor tactics to directly challenge the government. “Resist tyranny, join a union,” is now a protest slogan.

The people who founded The 70’s Biweekly are no longer on the front lines. After his arrest by the Beijing government in 1981, Ng worked as a journalist; he died of cancer in 1994. Mok is now an artist working in film and underground theater. He eventually created a theatrical production based on his late friend’s life.

The collective they cofounded may not have been able to sustain a mass movement. Nonetheless, The 70’s Biweekly’s dedication to organizing students and workers, its demands for new kinds of engagement, informed the Hong Kong political scene far beyond the publication’s brief lifetime. Its most enduring lesson may be that the model for liberation can only be found in solidarity with all marginalized people—that no single dogma or past experience can show us how to do that best. In a fight that involves millions, the Hong Kong left is still finding its way forward.