Displaced by a War, There’s No Way Back Home

Decades after the Bosnian War, refugees still live out the aftermath of their displacement in former Yugoslavia.

At the onset of the Bosnian War in 1992, Hazira Đafić fled Srebrenica with her brother Merfin and her one year-old son. Soon after reaching safe-haven, she and her family were moved into a temporary refugee settlement built by the international community called Ježevac, near Tuzla in eastern Serbia.

For over three decades, Hazira has been living in utmost precarious conditions – often without running water, basic sanitary needs, and means of survival. She shares this fate with people across the region of former Yugoslavia, individuals and communities who remain displaced and live in temporary refugee settlements, for whom the war and its consequences have hardly ended.

“I was born five years after the war, and yet I am born into displacement. I am born a refugee,” says Salčin Isaković. “Of course, many have lost their relatives during the war, but here in [the] Višča settlement where I live, it feels like we relive those losses every day.”

Višča, Karaula, Belvedere, Mihatovići, Ježevac, Sokolac, Barake, Mrdići, and various other still-active refugee settlements are a sphere where the remnants of conflict are omnipresent. In these camps, war has reproduced precarity and made it visible in the form of everyday life.

But these refugee settlements are also a source of a counter-narrative—of the many lost, unspoken, or unheard histories of the displaced communities. Refugee settlements in the region often become spaces where the culture, heritage, and destiny of those who were subjected to annihilation are preserved.

This photography project is a collaboration with permanently displaced people whose only sense of home is in memory, and whose acts of storytelling are ultimate acts of resistance.

10 years after the Dayton agreement that officially ended the conflict, Hazira’s brother Merfin stepped on a landmine near a refugee camp and died.

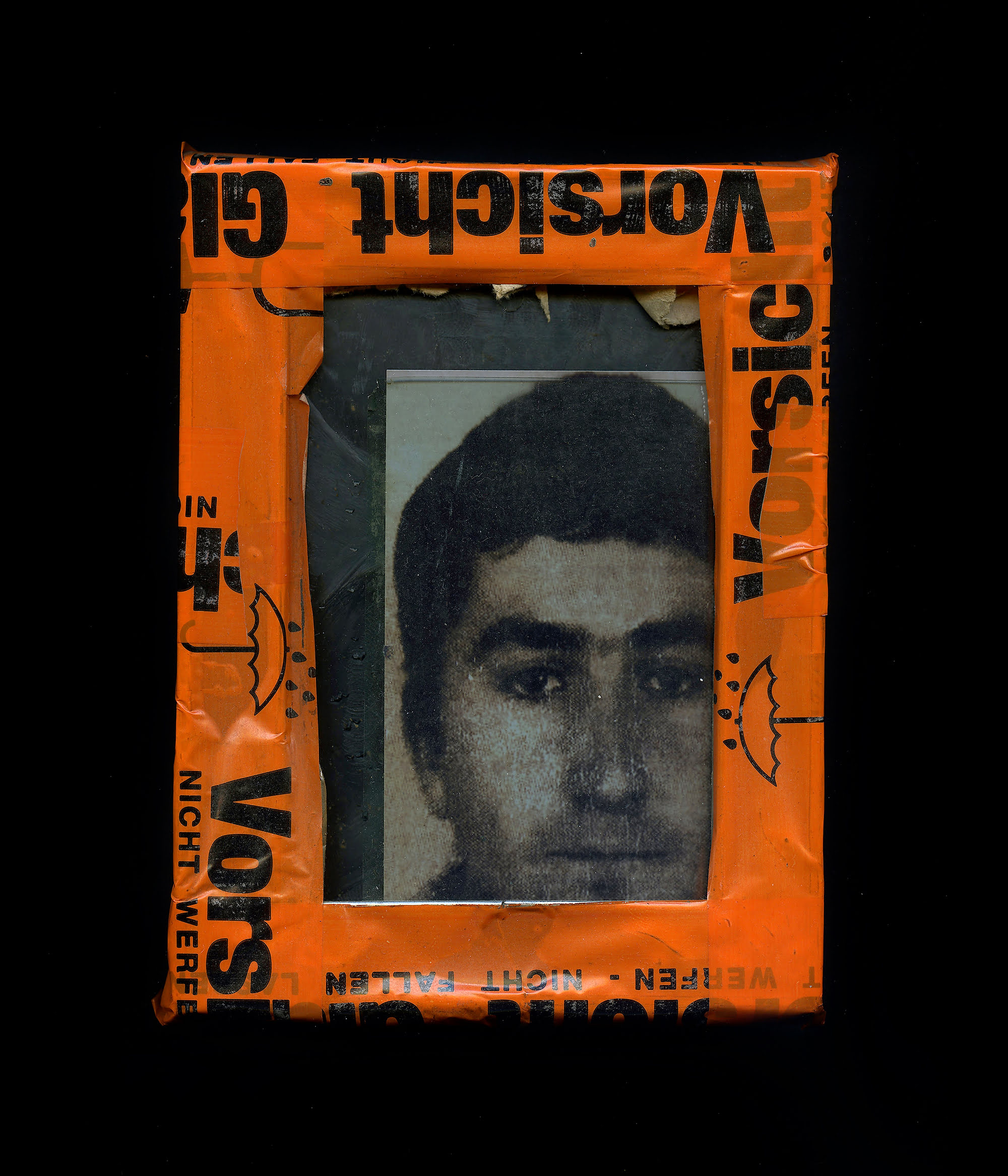

Hazira later framed his obituary photograph in a broken frame and tapped over it with the only tape she had: an orange safety tape with German printed on top of it. The warning, among others, reads: Nicht Fallen (do not fall).

Besides this photograph, I have nothing of his left.”

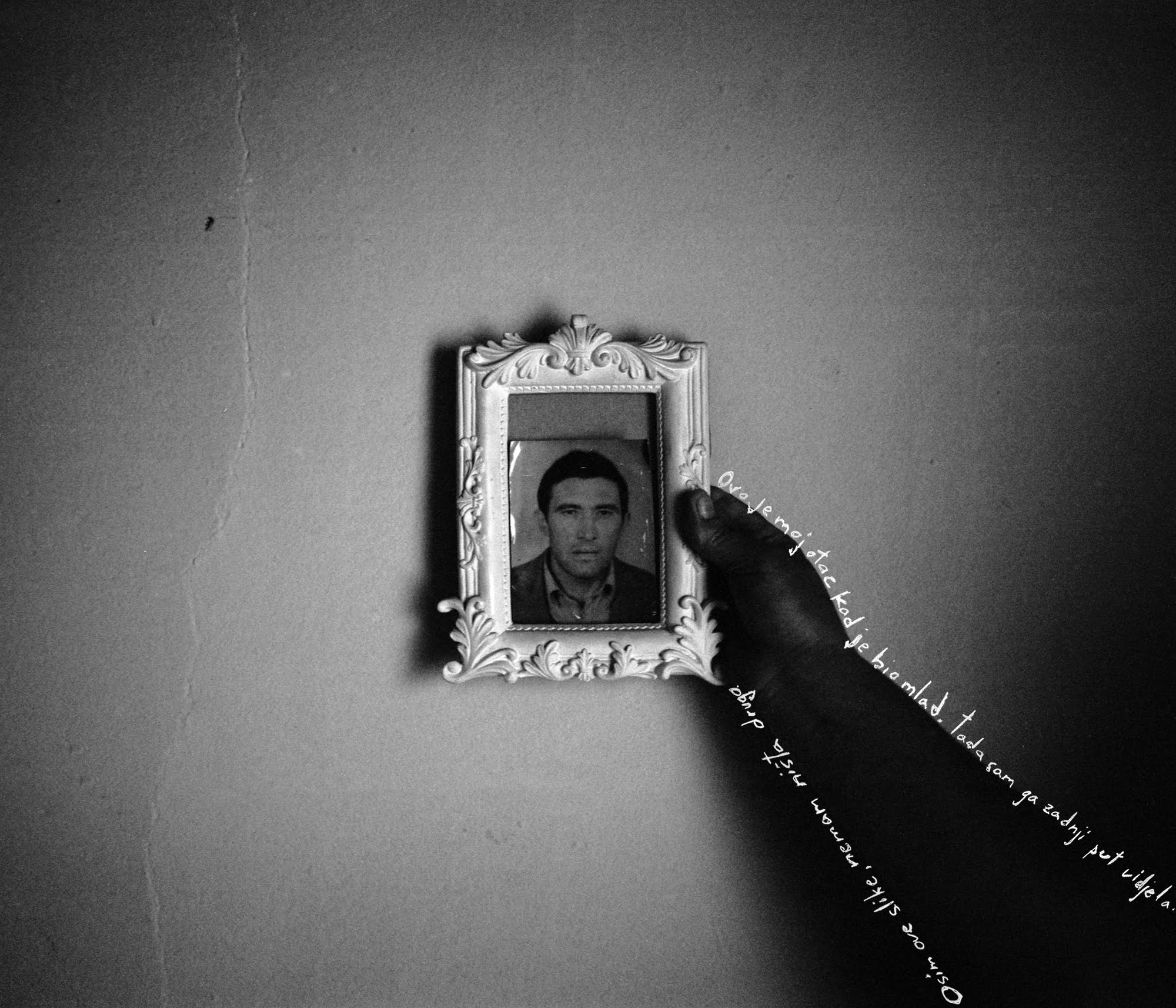

Mirsada Beganović’s only image of her father, who was killed in Srebrenica.

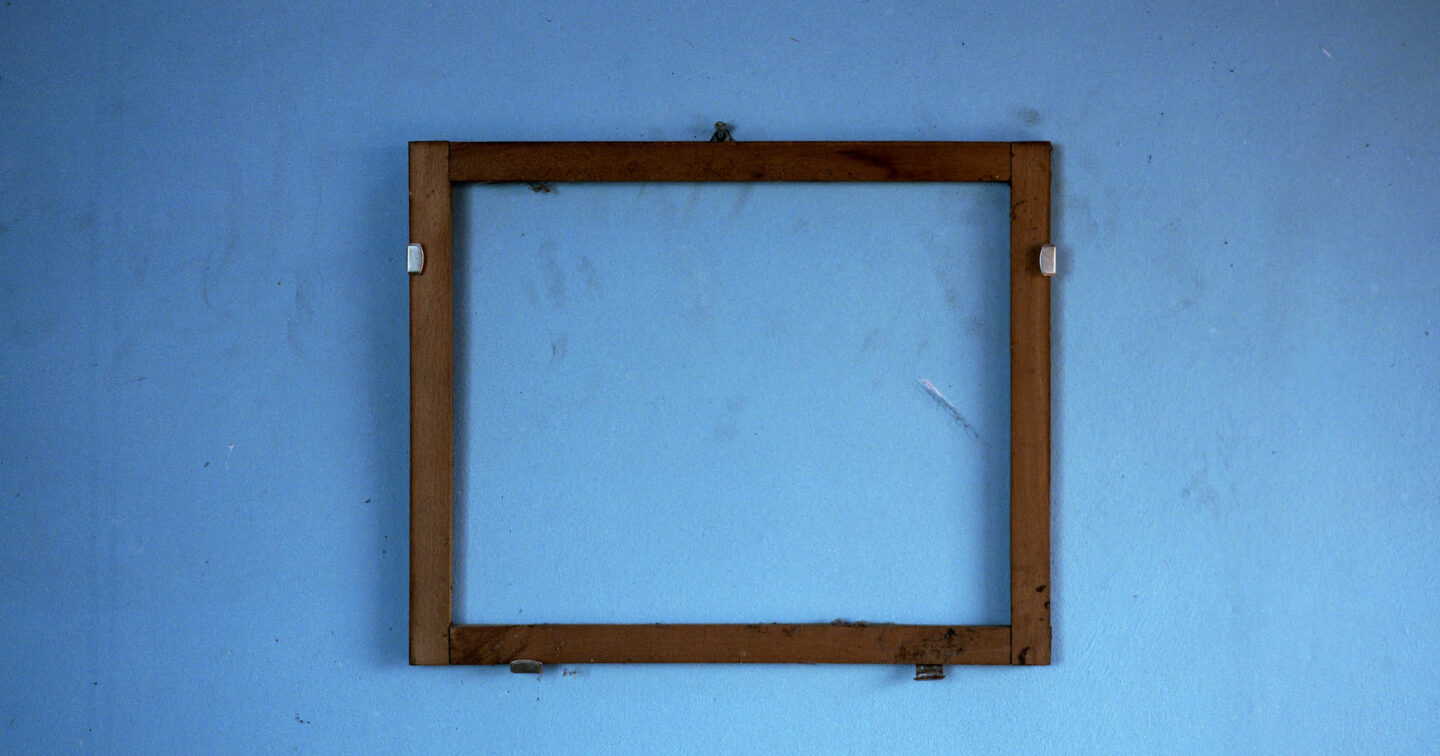

Asima does not have a single image of her family from before the war.

“The empty frame,” she said “helps me imagine how life used to be.”

March 2021.

November 2021.

Hazira Đafić washes hands in the puddle, after looking for coal that she sells on the black market.

“Coal is the bread and butter for us refugees,” she and her husband Zaim would often say, as there are no opportunities for them to find regular employment.

As the local municipality does not pick up garbage from refugee settlements, the residents burn their waste.

They call it the volcano of Ježevac.

In Mihatovići refugee settlement. Bosnia and Herzegovina. January 2020.

Bosnia and Herzegovina, May 2023.

Bosnia and Herzegovina. February 2023.

Bosnia and Herzegovina. March 2021.

“When I sleep, sometimes I visit my home village.”

Hazira on her doorstep in the Ježevac refugee settlement, Bosnia and Herzegovina. February 2023.

“This was Ševko’s first birthday. Two years later we were in the concentration camp in Vlasenica.”

Nezira and her son Ševko’s only photograph from before the war.

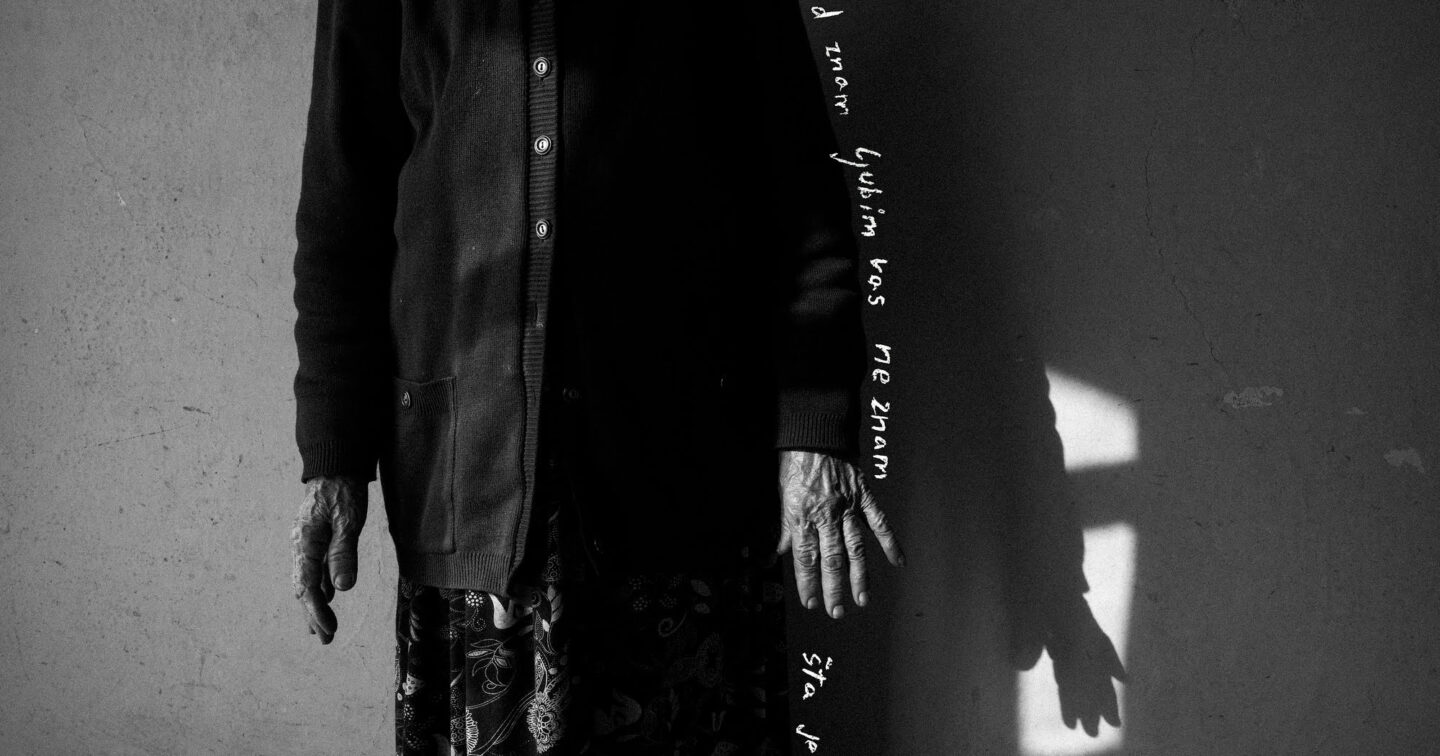

“When she fled, Nena first lived in Kiseljak, and then came to Mihatovići in 1998. She had four sons, but only one of them survived. She has suffered a lot. It was too much for her, all this sadness.”

The account of Nena and her arrival to Mihatovići refugee settlement by her neighbour Nezira Musić. Bosnia and Herzegovina. January 2020.

This story was made with support of The Aftermath Project, as the winner of its grant for 2023.

The Aftermath Project is a non-profit organization committed to telling the other half of the story of conflict — the story of what it takes for individuals to learn to live again, to rebuild destroyed lives and homes, to restore civil societies, to address the lingering wounds of war while struggling to create new avenues for peace.