David Nasaw’s Unsparing Tour of America’s World War II and Its Aftermath

A gimlet-eyed and honest accounting of the war’s hidden costs that still affect us today.

Let’s you and I start honestly here: World War II is part of an ever-more-distant national past—one that, given the troubles we’re now in, likely hasn’t been at the top of your mind these days. Yet even now, 80 years on, that war is worth our serious reflection for reasons I’m about to explain, thanks to David Nasaw’s sterling new book, The Wounded Generation.

All of us have some basic knowledge—or at least some sense—of that war and its importance. It was the bloodiest global war in human history, with more than 70,000,000 million lives lost in six years—and it set the stage for the Cold War, which for nearly a half century afterward placed the Damoclean Sword of nuclear obliteration over us all.

And yet many of us reflexively think of it as America’s “last good war,” not only because it was fought against real fascist enemies but because we were able to clearly defeat them—something we’ve not since been able to do against our declared enemies in Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, the Balkans, Iraq, Iran, Syria, or Afghanistan. (Congress hasn’t officially declared us at war since Pearl Harbor—and our invasions of Granada and Panama don’t deserve being called “victories,” let alone “wars.”)

Nasaw wants us to revisit America’s role in that “last good war,” in order to probe its human costs on warriors and civilians alike, and to recalculate the price we paid for defeating fascism in its original malignant form. Because over 99 percent of World War II veterans are dead now, in their place what we have left are stories, stories that for Nasaw bear weak—and too often dishonest—resemblance to the lived experiences of those years of war and its aftermath.

In 1998, TV journalist Tom Brokaw published The Greatest Generation, an instant bestseller that bathed the men and women of the Depression and World War II in a golden haze that so captured popular imagination that I dare say no one born since 1945—no Boomer, Gen Xer, Millennial, or Zoomer—fails to catch the reference.

By happenstance, historian Stephen Ambrose had just published Citizen Soldier, his moving recollection of the “ordinary” men who’d fought their way from Omaha Beach to victory on the Rhine. That same year Stephen Spielberg released Saving Private Ryan (with Tom Hanks leading his own band of “ordinary” Americans) into 2,500 theaters to instant and wide acclaim. (Private Ryan eventually grossed nearly $500 million at the box office.)

As luck would have it, that year also marked the apogee of influence for social theorist Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man. In it, Fukuyama had proclaimed the triumphal worldwide march of liberal democratic capitalism as a new age that might last… well, forever. Set alongside Brokaw’s, Ambrose’s, and Spielberg’s works, The End of History provided what amounted to historical Golden Bookends—Brokaw’s celebrating a Golden Past, Fukuyama’s holding out a Golden Future.

Their arrival enthralled the country’s talking classes because the timing seemed—at that moment at least—almost perfect: America at the 20th century’s end was in the midst of its own momentary Golden Now. The dot.com bubble was still bubbling, 9/11 three years away, the Great Recession 10 years, and Donald Trump a barely recognized bankrupter of New Jersey casinos.

The evidence for that Global Now was everywhere, it seemed. Globally, the United States hubristically declared itself “the world’s only superpower” because the Soviet Empire had collapsed and booming China was still then more curiosum than foreboding challenge. At home, what opinion writers anointed the “New Economy” was amid the longest uninterrupted expansion in US history, and glittering new fortunes were everywhere. The stock market was booming, thanks to globalization, 401Ks, LBOs, IPOs, and dot-coms. (Novelties such as laptops, cell phones, and the Palm Pilot were all the rage—and thanks to AOL, Netscape, and Windows 95, something called the “World Wide Web” was said to promise even more.)

As chief political apostle, balladeer, and barker of this new age (known alternately as “The Third Way” or “neoliberalism”), Clinton declared that its successful partnering of big government and big business was fostering a “revolution” in how to think about government and business alike. With “public-private partnerships” Washington’s ubiquitous new policy model, and “welfare reform,” NAFTA, and the WTO his biggest achievements, he’d proudly declared that “the era of big government is over.”

That, of course, also turned out not to be true—but one thing that was over, thanks to neoliberalism plus the explosive growth of Silicon Valley and Wall Street, were Washington’s massive deficits, deficits that had swelled under Democrats and Republicans alike for nearly 50 years. Now, thanks to the wisdom of Clinton’s fiscal (plus Alan Greenspan’s monetary) austerity, the federal government had begun to run surpluses—something Washington hadn’t done since Eisenhower. What’s more, among economists and policy types, there was excited talk not just about “deficit reduction” but about “debt liquidation”—paying off the entire $6 trillion federal debt as early as 2010, something the country hadn’t done since Andrew Jackson’s presidency in the 1830s.

Needless to say, today—with federal debt approaching $40 trillion (that’s over 100 percent of GDP), and the deficit nudging $2 trillion annually—we live in a different world today.

But if the Golden Now is gone, and the Golden Future flickers chimerically to all but our MAGA president and his cultists, what about our erstwhile Golden Past, and in particular the Greatest Generation’s role in creating it?

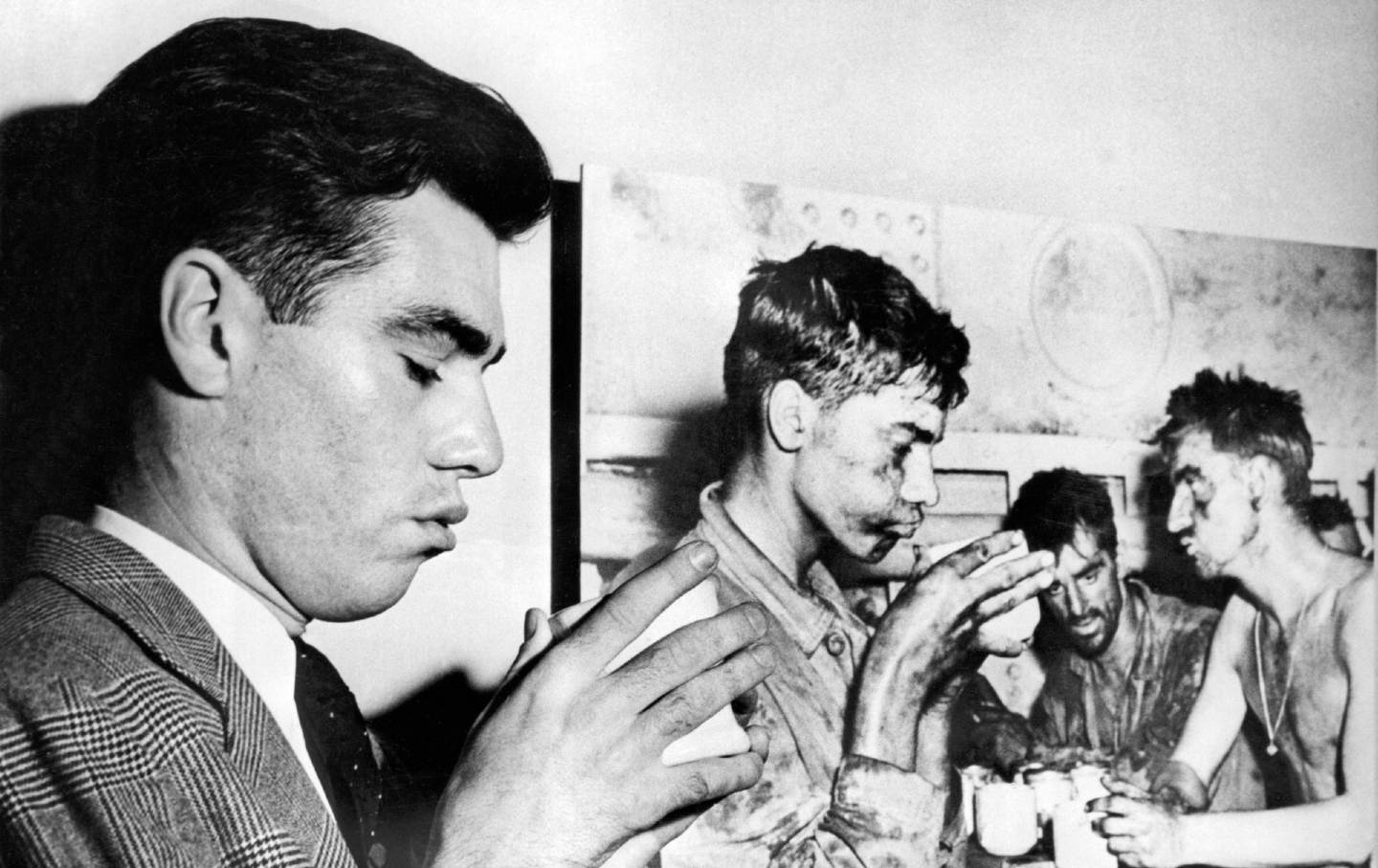

David Nasaw thinks we owe Brokaw’s (and Ambrose’s and Spielberg’s) tale-telling and its legacy a second, and much more gimlet-eyed, review—a much more honest accounting of the war’s hidden costs that still affect us today.

The Wounded Generation is a minutely detailed and meticulously documented tour—and an unsparing one—of America’s World War II and its aftermath. Told over 400 pages, it isn’t meant to belittle but to understand the story of the actual, not the en-fabled, lives of the 16,000,000 Americans who served in World War II as well as the tens of millions more who remained behind. Officially, over 400,000 Americans died and nearly 700,000 were wounded in less than four years of war—but Nasaw wants us to cast an unblinking eye on the millions more who were never counted (or at best undercounted), who suffered wounds and mistreatment that haunted the decades following. In doing so, he’s reminding us of what is still a too-familiar story, that of our obdurate divisions by race, gender, region, and class—and of a would-be liberal government whose most important efforts to mitigate the war’s harms too often failed far too many.

The book’s subtitle, Coming Home After World War II, is misleading because, although the first half of the book is about the war years themselves, the second half takes us through the early postwar years and into the 1950s in a way that novelly reconnects those war-formed years to the boomer generation and its own era-defining war in Vietnam—and forms, for an attentive reader, a through line that connects through Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan to our Ukraine- and Gaza-haunted world today.

The book’s structure relies on two narrative drivers—one chronological, the other topical—that Nasaw deftly orchestrates. Starting with the draft that began in 1940, The Wounded Generation immediately reminds us what the Depression and a much longer history of extensive poverty had already done to Americans’ health and well-being: Nearly half of the 19,000,000 men drafted were rejected, for physical and mental health reasons—as well as for the illiteracy of hundreds of thousands, white and black alike.

In the first two years of the war, the sheer violence and mayhem of battles like Guadalcanal and Anzio Beach meant that another 400,000 men had to be mustered out because of what was called “combat fatigue.” (By war’s end, nearly a quarter of American casualties would be classified as “psychiatric.”) Given in most cases minimal medical attention (PTSD wouldn’t be diagnosed until Vietnam), hundreds of thousands of men were sent home carrying mental and emotional scars that, in far too many cases, lasted a lifetime.

As the fighting ground on in Europe and the Pacific, casualties mounted precipitously and so more were drafted—and yet more and more men were also discharged, and not just for “combat fatigue”: the US military was rigidly segregated until 1948, and racial and sexual discrimination was rife. Less than honorable “blue discharges” were issued to more than 50,000 for “undesirable traits” such as homosexuality, while race determined who served and where, and thus who was wounded and who died. Because prejudice and poverty afflicted so many communities of color, of the 2,500,000 African Americans drafted, over 60 percent were rejected—with those who were inducted assigned to segregated units far from actual combat, serving as truck drivers, longshoremen, cooks, cleaners, and construction workers. (The humiliation of racism had, however, one ironic benefit: Fewer than 1,000 African Americans died in combat.)

But what about the rightly celebrated Tuskegee Airmen—or the Navajo code-breakers or the Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the war’s most decorated unit? All, Nasaw says, fully deserve their accolades—but were in truth only a tiny minority of the minorities who served in World War II.

As the war drew to a close in 1945, millions began their return to civilian life, where new challenges emerged. One was eligibility for early return. This was governed by a “points” system frequently mismanaged by officers in often deeply unfair ways. An Army survey shortly after the war found enlisted men consequently deeply angry: Three-quarters said most officers put their own welfare ahead of their men, and 90 percent said that “too many officers take unfair advantage of their rank and privileges.”

Back in Washington, the spirit of the New Deal lived precariously between everyone’s desire for immediate demobilization and new demands for a postwar military that would be permanent, enormous, stationed worldwide, and at the center of what would soon be called the Cold War.

During World War II, Roosevelt and his allies had not planned for that Cold War but for the return of America’s warriors with the most generous veterans’ benefits in the country’s history: a weekly “transition allowance,” the promise of housing assistance and GI mortgages, and most famously, the promise of a free (or heavily subsidized) college and trade school education.

But it wasn’t enough: Jobs were an immediate issue on return. On the home front, some 7,000,000 women were working outside the home by war’s end, and according to a Ladies Home Journal poll, three-quarters of them “enjoyed working more than staying at home.” As the men came home, however, women left their jobs—some willingly, some not. Even so, many of the men—who by law were supposed to get their prewar jobs back—found that employers had “redefined” the jobs (or deskilled or discontinued them), leaving lower-wage and part-time work the only alternatives.

Even with a job, for millions there was almost no affordable housing. Home construction had collapsed in the Depression and so “home, sweet home,” as The New York Times reported in late 1946, “is a nightmare crisis instead of a song…. thousands of families are doubling up, living in substandard dwellings, even sleeping in cars, sheds, railroad stations, streets, garages…or even in a pup tent, school or filling station.”

A year after the war, nearly a million homes were finally under construction compared to 150,000 three years earlier. But that new number was nowhere near the need—and once again, race, sex, and class intruded. Low- and even middle-income white veterans found mortgages hard to get—ultimately only a quarter of white veterans qualified, and for veterans of color the picture was far starker: Even when they did rarely get GI mortgages, realtors and developers refused to sell to them. “As a Jew, I have no room in my mind or heart for racial prejudice,” William Levitt of Levittown fame said in trying to justify why Levittowns refused to sell to “Negroes” (whether veterans or not): “Our position is simply this: We can solve a housing problem, or we can try to solve a racial problem. But we cannot combine the two.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The GI Bill’s education benefits carried their own problems. The bill provided billions in federal funding but left control over what schools and programs would qualify and who would be eligible to state and local authorities—a division Southern Democrats had insisted on for their support. So because at war’s end 60 percent of white and over 80 percent of black veterans lacked high school degrees, they couldn’t get GI college assistance—and in 17 Southern states, segregation meant black GIs with high school degrees were admitted only to the few historically Black colleges—which were quickly overenrolled, forcing rejection of a majority of the applicants.

I came away from Nasaw’s 400 pages with more rather than less admiration for the men and women of World War II individually—but it’s an admiration now tempered with a far deeper understanding of the systemic roadblocks the nation, its prejudices, and its ambitions put in their way.

I also came away with greater respect for Nasaw. Of his eight books, The Wounded Generation feels, more than earlier volumes, like a work in some way of love and reconciliation. Late in the book, I came across a brief paragraph that mentioned en passant both the war-induced alcoholism and the postwar death of Joshua Nasaw—one of many individual stories David Nasaw shares.

Joshua Nasaw was an Army medical officer who was mustered home after a midwar heart attack—and who then lived on until 1970, when he died of a second heart attack the VA rated as “service-related.” His son writes nothing more—but a few pages later, quotes another author thus:

Ignored in any “good war” narratives is…what really happened overseas—and most important, what occurred after the men came home. Many families lived with the returnee’s demons and physical afflictions. A lot of us grew up dealing with collateral damage from that war—our fathers.

David Nasaw should be proud of what he’s written here. Rather than tell the story of his father, he has given us a story of his father’s generation—one steeped in authentic complexity, including moral ambiguity.

I think a good number of the men and women who served in what we too easily call our “last good war” would thank him if they could.

More from The Nation

The Trump Administration Arrested Don Lemon Like He Was a Fugitive Slave The Trump Administration Arrested Don Lemon Like He Was a Fugitive Slave

Lemon’s arrest is not only a clear violation of the First Amendment but also a blatant throwback to the Constitution’s long-discarded Fugitive Slave Clause.

Want to Support the Fight Against Fascism? Boycott Trump’s World Cup. Want to Support the Fight Against Fascism? Boycott Trump’s World Cup.

In this week’s Elie v. U.S., The Nation’s Justice correspondent urges soccer lovers to stay away, takes on the attacks on Alex Pretti, and warns of a dangerous anti-voting bill.

ICE Brutally Dragged This Disabled Woman Out of Her Car. What Happened Next Was Just As Chilling. ICE Brutally Dragged This Disabled Woman Out of Her Car. What Happened Next Was Just As Chilling.

“They laughed at me and told me this wouldn’t have happened if I was a ‘normal’ human being,” Aliya Rahman tells The Nation.

Manhattan Republicans Get a Lesson in Mamdani-Era Self-Defense Manhattan Republicans Get a Lesson in Mamdani-Era Self-Defense

A New York Republican club hosted a seminar dwelling on vigilante fantasies in one of the nation’s safest cities.

The Smug and Vacuous David Brooks Is Perfect for “The Atlantic” The Smug and Vacuous David Brooks Is Perfect for “The Atlantic”

The former New York Times columnist is a one-man cottage industry of lazy cultural stereotyping.

The Cartoonist, the Director, and the Sex Workers The Cartoonist, the Director, and the Sex Workers

Sook-Yin Lee’s new romantic comedy, Paying for It, explores Platonic love and prostitution.